Lions weren’t the only dangerous-game animals Col. Patterson pursued in Tsavo. Here, he relates how his first time hunting hippo was almost his last. An excerpt from The Man-Eaters of Tsavo.

By the light of a splendid full moon we settled ourselves on a great outspreading tree branch and commenced our vigil. Soon the jungle around us began to be alive with its peculiar sounds—a night bird would call, a crocodile shut his jaws with a snap, or a rhino or hippo crash through the bushes on its way to the water. Now and again we could even hear the distant roar of the lion. Still there was nothing to be seen.

After waiting for some considerable time, a great hippo at last made his appearance and came splashing along in our direction, but unfortunately took up his position behind a tree which, in the most tantalizing way, completely hid him from view. Here he stood tooting and snorting and splashing about to his heart’s content. For what seemed hours I watched for this ungainly creature to emerge from his covert, but as he seemed determined not to show himself I lost patience and made up my mind to go down after him.

I therefore handed my rifle to Mahina to lower to me on reaching the ground, and began to descend carefully, holding on by the creepers which encircled the tree. To my intense vexation and disappointment, just as I was in this helpless condition, halfway to the ground, the great hippo suddenly came out from his shelter and calmly lumbered along right underneath me. I bitterly lamented my ill-luck and want of patience, for I could almost have touched his broad back as he passed. It was under these exasperating conditions that I saw a hippo for the first time, and without doubt he is the ugliest and most forbidding looking brute I have ever beheld.

The moment the great beast had passed our tree, he scented us, snorted loudly, and dived into the bushes close by, smashing through them like a traction engine. In screwing myself round to watch him go, I broke the creepers by which I was holding on and landed on my back in the sand at the foot of the tree—none the worse for my short drop, but considerably startled at the thought that the hippo might come back at any moment. I climbed up to my perch again without loss of time, but he was evidently as much frightened as I was and returned no more. Shortly after this we saw two rhino come down to the river to drink; they were too far off for a shot, however, so I did not disturb them, and they gradually waddled upstream out of sight.

Then we heard the awe-inspiring roar of a hungry lion close by, and presently another hippo gave forth his tooting challenge a little way down the river. As there seemed no likelihood of getting a shot at him from our tree, I made up my mind to stalk him on foot, so we both descended from our perch and made our way slowly through the trees in the semi-darkness. There were numbers of animals about, and I am sure that neither of us felt very comfortable as we crept along in the direction of the splashing hippo; for my own part, I fancied every moment that I saw in front of me the form of a rhino or a lion ready to charge down upon us out of the shadow of the bush.

In this manner, with nerves strung to the highest pitch, we reached the edge of the river in safety, only to find that we were again balked by a small rush-covered island, on the other side of which our quarry could be heard. There was a good breeze blowing directly from him, however, so I thought the best thing to do was to attempt to get on to the island and to have a shot at him from there. Mahina, too, was eager for the fray, so we let ourselves quietly into the water, which here was quite shallow and reached only to our knees, and waded slowly across.

On peering cautiously through the reeds at the corner of the island, I was surprised to find that I could see nothing of the hippo; but I soon realized that I was looking too far ahead, for on lowering my eyes there he was, not 25 yards away, lying down in the shallow water, only half-covered and practically facing us. His closeness to us made me rather anxious for our safety, more especially as just then he rose to his feet and gave forth the peculiar challenge or call which we had already heard so often during the night.

All the same, as he raised his head, I fired at it. He whirled round, made a plunge forward, staggered and fell, and then lay quite still. To make assurance doubly sure, I gave him a couple more bullets as he lay, but we found afterwards that they were not needed, as my first shot had been a very lucky one and had penetrated the brain. We left him where he fell and got back to our perch, glad and relieved to be in safety once more.

As soon as it was daylight we were joined by my own men and by several Wa Kamba, who had been hunting in the neighborhood. The natives cut out the tusks of the hippo, which were rather good ones, and feasted ravenously on the flesh, while I turned my attention with gratitude to the hot coffee and cakes which Mabruki had meanwhile prepared.

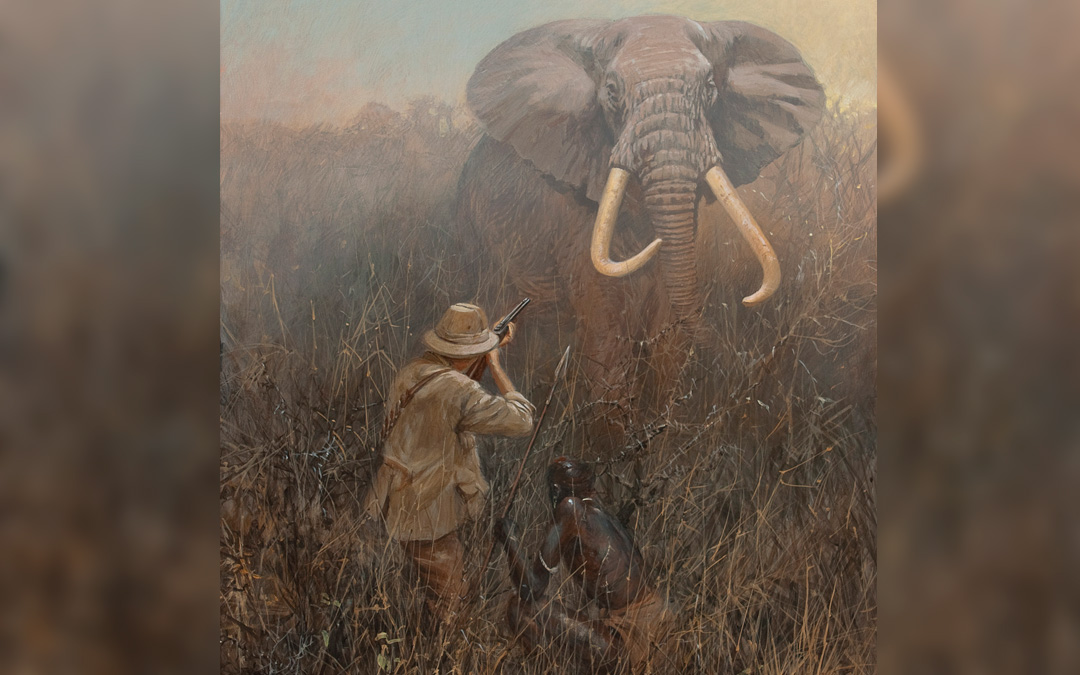

Sporting Classics has compiled this remarkable anthology showcasing the best African adventures published in our award-winning magazine.

Sporting Classics has compiled this remarkable anthology showcasing the best African adventures published in our award-winning magazine.

Ruark, Capstick, Roosevelt, Markham – the legends in outdoor literature are all here, sharing their stories of deadly encounters with dangerous game, of bizarre run-ins with witch doctors, gorillas and man-eaters, of safaris into the uncharted wilds of deepest Africa.

Illustrated by world-renowned artist Bob Kuhn, AFRICA features more than 400 pages of unforgettable stories by some of the finest professional hunters and writers of sporting adventure. Buy Now