There is an old rifle in my gun rack that I haven’t fired for years. We all, I suspect, have one. Perhaps it was your dad’s or granddad’s, maybe your mom’s or grandma’s, or maybe a relic of a firearms fascination fulfilled long ago. So it is with me.

Coming of centerfire age in East Tennessee in the 1960s, I made a list of rifles that, someday, I’d like to own. Ground hogs abounded; whitetails and bear were around but few. My dream rifle must handle all three. Topping the list was a pre-’64 Winchester Model 70 in .257 Roberts. All the premier gun scribes, foremost among them Jack O’Connor and Townsend Whelen, were singing the cartridge’s and the rifle’s praises.

About the same time I made my list, Winchester released its cheapened version of the Model 70. Prices for pre-’64 rifles skyrocketed and, though not the rarest chambering, those in .257 Roberts soared far beyond my means. Decades rolled on until, in the mid-’90s, after selling a guide to North America’s greatest fishing lodges, one appeared on the rack at my local gun shop. I splurged.

The stock had a few blemishes, as did the bluing. None of the screws were scarred from ill-fitting screwdrivers, and the barrel bedding screw halfway up the forend was not missing. Sure, it had been used, but it hadn’t been abused or refinished.

When I checked its serial number, I discovered I’d been more than lucky. The rifle came off the line at New Haven in 1953. Its barrel had been rifled and lapped by hand, a process that took 11 minutes and produced superior bores. No wonder Model 70s of that vintage earned the sobriquet “The Rifleman’s Rifle.” Sadly, to save money, Winchester switched to button rifling in 1955—serial number ~323,000—and barrel quality took a hit.

Consistent bench technique is the key to knowing how well your rifle really shoots.

When I got it home, I stripped the barreled action from its stock, scrubbed the bore with JB bore cleaner, set the trigger to break at 40 ounces with next to no overtravel, and topped it with a Leupold 2.5–8 VX-3. The rifle wasn’t a fan of factory ammo, but handloaded Barnes 100-grain TSX bullets shot into an inch, sometimes less, and kept the freezer full of venison. Thinking it would be cool to scope the rifle with glass of similar vintage, I mounted a Baush & Lomb Balvar 8 dating from 1959 in that firm’s rings and bases, which are adjustable for elevation and windage, as the scope itself is not.

Changing circumstances ended my handloading days, and my supply of its favorite ammo dwindled. Down to my last half-box, I wondered how the fine old rifle would perform with today’s factory rounds, which are loaded to much more precise standards than offerings 20 years earlier.

No better time to find out than summer when traffic at the range is scant. I obtained a couple boxes each of Nosler’s 100-grain ballistic-tip and Partition loads, as well as their 115-grain ballistic-tip ammo. Hornady provided 117-grain SST ammo.

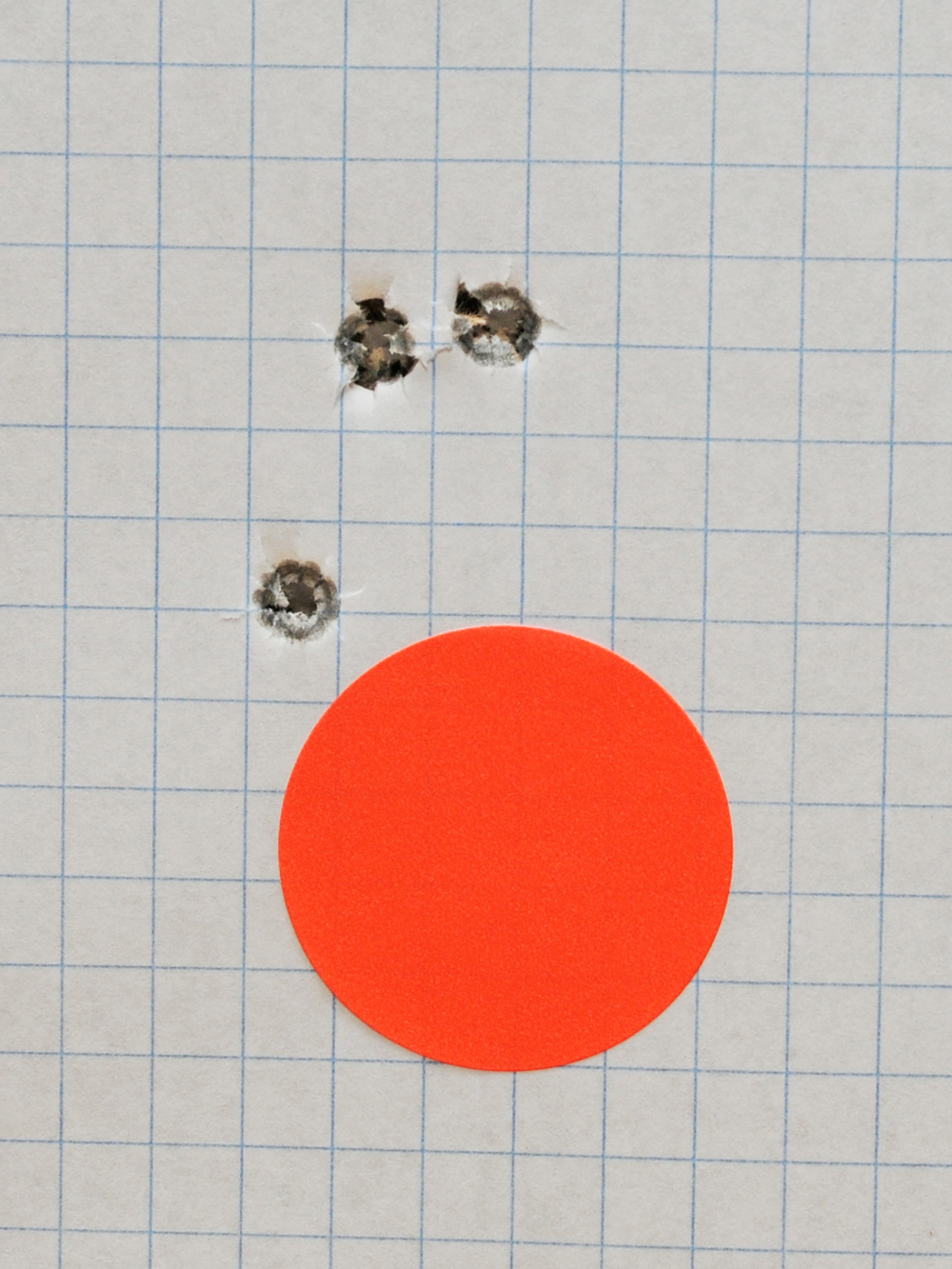

Hunting accuracy is determined, I believe, by three shots, no more, from a cold, clean barrel. Nobody I know hunts with a rifle with a hot, dirty barrel, so why test ammo or sights in that way? I’d fire three shots, clean the barrel, let it cool, and then fire three more, repeating the process until I’d produced five three-shot groups. The average spread would give me a pretty good idea of how the rifle handled each factory loading.

Taking a page from benchresters, I’d learned that a precise aiming point—the smallest target I could center with the crosshairs—always produces the tightest groups. From an office supply store, I bought a packet of 1¼ fluorescent red dots and a pad of 11×17-inch graph paper marked off in ¼-inch squares. Not only do I have an endless supply of fine targets, but each group’s size is easily read and indisputable.

Consistency is the key to evaluating ammo performance. Shoot from an immovable bench. Rest butt and forend solidly on sandbags. Position your face on the cheekpiece so that your shooting eye sees the scope’s full view. Hold the rifle comfortably but tightly. Squeeze the trigger slowly and firmly. Always do this, whether testing for best ammo or sighting in, and you’ll be amazed at how well your rifle shoots. And even if it doesn’t, you’ll know the reason most likely wasn’t you.

Sighting in is easy with homemade red-dot targets on graph paper.

I have to report that I was utterly amazed at the groups that my 64-year-old, full-factory Model 70, with its antique scope and my ancient eyes, produced with today’s ammo. All three loads delivered groups averaging less than an inch and a quarter. Often three of the five test groups with each load spanned little more three quarters of an inch. I settled on Nosler’s 115-grain ballistic tip, although Hornady’s 117-grain SST shoots a little faster and flatter. Near as I can tell, there’s not more than a smidgeon of difference between the two.

Come deer season, it’ll be pure joy to hunt with Mr. Robert’s quarter bore. Aged this rifle/cartridge combo may be, but I can tell you one thing for “sartin,” as they say in these parts: This old dog’ll hunt.