I’ve never been elk hunting before. I try to keep my excitement from wriggling in my stomach, but it’s no use; like trying to keep a moth in its cocoon.

I lie awake on the mattress on the floor of my bedroom. My apartment is in Salem, Oregon; I moved there five months ago for a government job. It’s nothing special, but it got me off the East Coast. At 27, it was past time to head West.

In the morning, I am going elk hunting near Packsaddle Park off Highway 22 toward Bend. I’ve never been elk hunting before. I try to keep my excitement from wriggling in my stomach, but it’s no use; like trying to keep a moth in its cocoon. I was going to hunt in Willamette National Forest, but the park ranger said the best action has been west of the dams, at least for the last couple of seasons. I am going to take his advice. What else can I do?

My eyelids are pressing down now. Tomorrow I’m going hunting. I need sleep.

The dawn drifts down through the treetops gray and uncertain. I’m halfway up Packsaddle Ridge, headed to a clear-cut near a cow farm. It’s hard climbing. My breath comes out in burning puffs that swirl in the pitiful red glow of my headlamp. I’m just thankful I haven’t tripped yet.

I finally crest the ridge just as the sun begins to spray its wan light over the forest. It’s a clear day, and I can see Mt. Jefferson, capped white with the streaks of gray and blue. I think how Jefferson looks like the mountains on the bottles of spring water. It’s 30 miles away, the park ranger told me. The orange winter sun climbs quickly to make the misty forest sparkle. Beautiful!

A rifle cracks sharp and loud, and I jump at the sound. That snaps me back. One less elk on the mountain.

Twisting around awkwardly, I slowly unzip a pocket on my pack frame, trying not to make a noise. I slip my hand in blind and feel the shells jingle softly at the bottom of the pocket. I retrieve five rounds of .338 Winchester Magnum and click them carefully into the magazine of my custom Mauser. I’m using a special handload: Speer 250-grain Grand Slams married to Federal Premium brass (the nickel-coated ones). The rifle feels heavy; the fancy European scope must add a pound at least. My thumbs massage the hand-cut checkering, and I look down at the swirling walnut and the little beads of moisture sitting on top of the oiled matte-blue, almost parkerized, receiver. It’s the most expensive firearm I have ever bought.

My gaze shifts from the rifle to an ancient Douglas fir, shimmering like a Christmas tree in wreaths of dewy tinsel. I smile down at the ground and shake my head. Packsaddle bumps and dips along its length, and the millions of triangular evergreens make the ridge seem like the scaly back of a slumbering dinosaur. The binoculars across my chest bounce against me as I scramble down a shallow trough then labor up to the top of the next bump. Finally, I reach the top and peel the big backpack off. It’s mid-October, but the spongy lumbar supports on the frame feel warm with sweat. Shading my eyes, I peer at the next bump up on the ridge. It must have been clear-cut a few years back. I sit down and lean against the trunk of a maple to observe the bald spot.

The sun is fully up now, and Jefferson’s slate and snow gleam so that I blink from the brightness. Through the tail of one squinting eye I catch a twitch of movement on the clear-cut. In a flash, the binoculars are out of their pouch. I scan the spot quickly. My mouth slacks open. Through the lenses, I see an elk too grand to even pray for—seven points on each antler, with the tips palmated in stately ivory crowns. His chest is a rug of hair the color of over-roasted coffee stretched over bunches of ropy muscles that bunch and roll with every step. His paunch sags but doesn’t sway, though it would have before the rut. He stops to nibble at the tips of a sapling.

The elk is 300 yards away, at least. I’ve never taken such a long shot; I never had to back East. I stand up and brace the Mauser against the trunk of the maple. Slowly, I work the bolt handle. The first case rim slots into the extractor with a tiny click. I slide the action forward and twist it into battery. The scope comes to my eye without a thought. I see the bull lumbering from sapling to sapling and wincing with each step on sprained ankles. My left thumb and index finger screw the magnification dial until I see the wet, silver sheen coating the hairs on his back. He slows, then he stops and shakes his coat like a dog.

I never hear the shot.

The locals have told me not to gut my elk—just skin and quarter it, they say—but I want to eat his heart. I tell myself next time I won’t gut the carcass. My hands work the bone-handled skinner up the stomach cavity. My mind races back to the first trout I caught off the reservoir dam 10 miles or so from here. I chuckle from the memory because that fish’s maw had sparkled from all the Powerbait. There’s no glitter in these guts.

Clouds blow in as I put the cape and antlers into the back seat of my car. Packing out the meat takes the rest of the day. As I close the trunk on the last hindquarter, I notice the Versa still has sky blue Connecticut plates. AG9201. I need to change them. I’m a Westerner now.

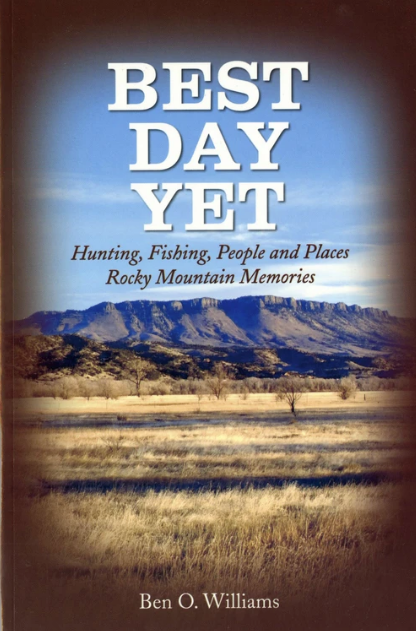

This book is a collection of the author’s true-shared essays of outdoor activities and of the folks he has encountered on the Great High Plains. It’s Ben’s Rocky Mountain Memories of hunting, fishing, people and places. This book has a far wider appeal than just for the hunting and fishing audience. No matter where you live, or what age, or in what walk of life you live, one of these essays will revive your memory of an experience in some way you had or someone in your family has handed down to you. Buy Now

This book is a collection of the author’s true-shared essays of outdoor activities and of the folks he has encountered on the Great High Plains. It’s Ben’s Rocky Mountain Memories of hunting, fishing, people and places. This book has a far wider appeal than just for the hunting and fishing audience. No matter where you live, or what age, or in what walk of life you live, one of these essays will revive your memory of an experience in some way you had or someone in your family has handed down to you. Buy Now