A father and son are finally reunited, on a secluded lake high in the Colorado Rockies.

On a clear June morning, I took my father bass fishing into the Colorado Rocky Mountains. I had not seen or spoken to him in ten years.

We ate an early breakfast at a truck stop on the outskirts of Denver; sitting at the counter occupying ourselves and our time by sharing a newspaper so we would not have to talk or look at each other. Glances at him through the mirror mounted on the wall behind the counter showed his 70 years, wrinkled skin, bags under his eyes and loose flesh under his chin. I made fleeting glances at his untrimmed white hair and gray whiskers on his cheeks and chin.

By mid-morning we had climbed above the pinion pines and were passing through stands of lodge-pole, bristlecone and blue spruce that thrived on rocky slopes and ridges. The aspen were beginning to turn, their golden leaves painting the high desert in natural pastels, and as we drove over a cattle guard, he said . . .

“You better find a spot to pull over. I’ve got to make water.”

I scowled at him. “You can’t wait?” The doctor in me was suddenly concerned about that, wondering if he had some internal problems, bladder or colon cancer that he didn’t bother to tell me about, and I hadn’t thought to check with his doctor in Portland before we left. He’d gone to the restroom right after we ate.

“No.”

After stopping, I soon found myself standing near him behind some trees relieving myself. Something we had done together many years ago, and laughed about it each time. I’d gone to the restroom before we’d left the truck stop, too. So much for my doctor worries.

To break the long silence that hung heavy between us after the stop, my father said, “You ever bass fish where we’re going?” His eyes never left the mountains in front of us as I drove.

“I have. We’re on a ranch that belongs to a friend.”

It was just past nine, but it felt like I had been with him all day. I was nervous and uncomfortable with Dad in the pickup – why? He was not the father I remembered – the stout man who worked in the lumber industry in Oregon until he retired; the man who carried me on his broad shoulders into the forest when I was little to watch him cut trees. He looked old now, frail and dependent. Why was it so hard for us to communicate?

“What’s up here besides fish?” he asked, as we drove slowly on a dirt road.

“Peregrine falcons, golden eagles and there’s coyotes, black and grizzly bear, mule deer, elk, cougars and wolves have been introduced back into the high country of Colorado.

“Hum.”

I hated him for my high school years when I was forced to chop limbs off felled trees so he could exceed his quota for the day, even though he paid me to do it. It was hard work under the hot summer sun – 10- to 14-hour days. Poison oak and ivy seemed to be everywhere. The axe was heavy and it had to be sharpened often to cut through leg-thick limbs, which had to pulled away from the trunk and stacked for burning, for my father insisted on perfection.

Then one hellishly hot afternoon I lost my temper and hit my father, then walked out of the woods and caught a ride to town in a logging truck. And with that one-sided explosion we grew apart, and stayed that way until I left home for college and never went back.

Looking back now; was I really forced? I tried to believe that I was; the money I’d made was certainly good back then. I had tried to brush off the bad memories, but it was difficult.

“How big are the bass?” he asked.

“Some run five pounds or more. I caught one last fall that took my closed fist in its mouth.”

“Hum.

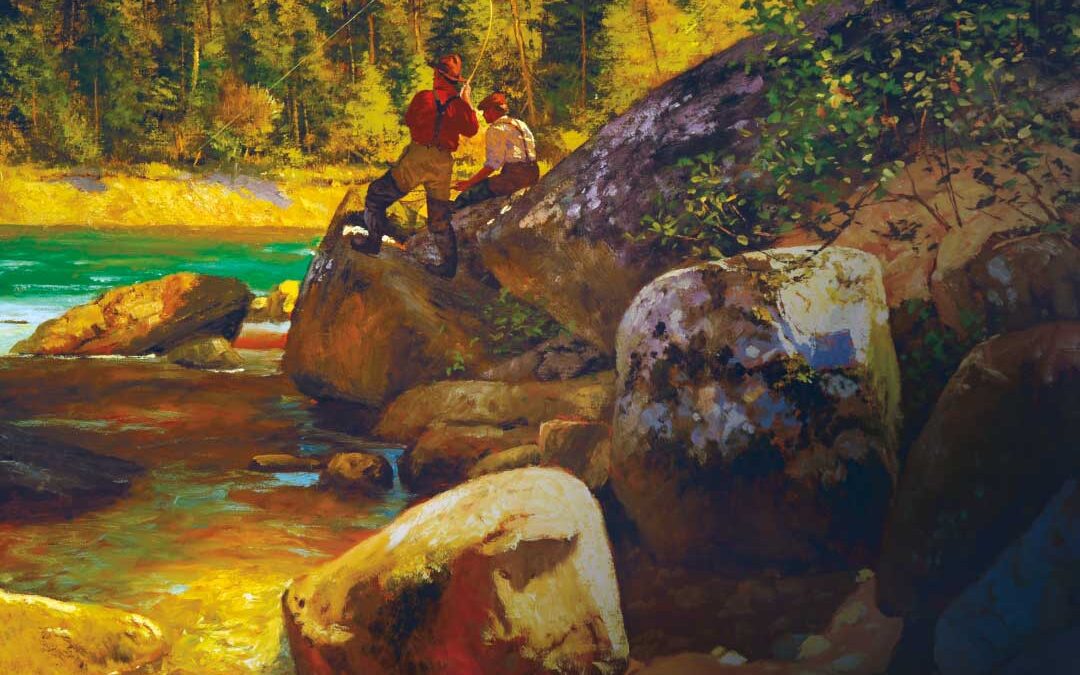

Mountain Shade by Brett James Smith

I had moved my father from Portland to Denver before the county stepped in and put him in a home. They had somehow gotten my address and telephone number, and called. He was doing things that bothered people, like brandishing a shotgun at neighborhood kids who batted softballs into his azaleas beds. The local police were involved too, concerned about him, taking the shotgun and warning him.

“Tell me about the place we’re going to?” He was looking at the Rockies closer now, snow still in the crags where the sun’s rays touched lightly for only an hour or two before moving on. Father had the window down, and the smells of timber, pine needles, desert sage and cool mountain air filled the cab.

It felt odd to be carrying on a conversation with my father after such a long absence. I was disturbed by it, uneasy that we were beginning to talk at all. I felt that he was pushing me, antagonizing me with his questions.

I remembered my small son’s words, and the look on his face that accompanied them when my family had the heated family discussion just three days ago about taking him fishing.

“It’s a series of quarries with a stream diverted through them. They were stocked with bass years ago, and have been pretty much left alone for a long time. You couldn’t ask for better conditions. Dan’s choosy on who he lets in and how often; and he’s downright religious about the ponds. Natural cover all around them – cattails, reeds, large cottonwoods, aspens and cliff rose. The quarries have developed into natural bass and panfish ponds.”

“Five pounds,” he said, later.

“Yes.” My wife and small son adored him, coddled him, and had pushed me into taking him fishing. I remembered vividly my losing argument.

“Honey, I haven’t spoken to him in ten years. I hate him.”

“Shame on you! He’s your father.”

Sherry gave me one of those wifely looks that said I was treading very close to deep water. “And you with all that education. A person would think you’d know better. I hope you don’t treat patients the way you treat him.”

“The fact that he’s my father doesn’t matter. I still hate him. What do we talk about? We have nothing in common. What if he refuses to talk to me? Can’t you just picture our day together?”

“He’ll talk, but you have to be a big person and stop hiding behind old memories that I’m sure were not that bad. And you better talk back.”

“I won’t do it.”

“Daddy, I like him,” my small son put in. “He’s got lots of stories to tell. Will you someday stop talking to me, too?”

What does a father say to that?

We parked the truck down the mountain about a mile, and by the time we came to the first quarry, it was near noon. I carried his stuff and mine, and had to stop often so he could catch his breath. My clothes clung to me from the exertion and heat.

By the water, after watching him squint as he tried to thread line with trembling hands, I grabbed his rod, threaded line and tied on a bass plug. It was warm and sweat still beaded my forehead.

“You want me to throw it out, too?” I said, sarcasm dripping off every word.

“If I do, I’ll let you know.” He smiled and took the rod.

In my youth before rebelling, Dad had taken me out many times to fish and hunt. In the forests he worked, he always carried fishing gear; often fishing at noon and after the workday was over if there was time. I remembered that as I watched him. And I recalled when I went to get him in Oregon. He’d clutched a small picture of mom and me in his hand on the flight from Portland to Denver, perhaps knowing he’d never again see his home or the places he had been around all his life and had come to love.

His voice suddenly came out hushed when he spoke. “Damn, are we in heaven?”

“Colorado,” I said, not smiling. After I moved from home, my mother came to visit without him – one of those unspoken things that sometimes creep into family relationships that fester and grow. And after her death and burial ten years ago, we never kept in touch; no Christmas or birthday cards. Nothing.

He was looking at the pond when he suddenly placed a finger to his lips, whispered and pointed. “Some fishermen call this nervous water.”

Excitement oozed out of him in his facial expressions and how he moved his right arm out, pointing to the water.

“See how the surface is as smooth as polished marble? Looks dead, doesn’t it? Wasn’t that way three minutes ago. You don’t hear any frogs or crickets, do you – and the small panfish aren’t touching the surface anymore.

“You got a green Gizzard Shad?”

“Why?” Even as I asked, I was scrambling to get my tackle box open and dig delicately around sharp-pointed bass plugs that always seemed to be stuck together until I spotted a green Gizzard Shad. All the while I was doing it, I was asking myself why I was hurrying to do what he’d asked.

“Don’t ask. There isn’t time to explain, just tie one on. If you don’t have one of them, tie on a Deer Hair Popper, yellow and black. Surely you have one of those?”

He eyed me, exasperation etched across his face. “Damn-it boy, hurry! Things are about to erupt. Can’t you feel the electricity in the air, like lightning close in – striking and dancing along a barbed wire fence? I’ve seen both before, a long time ago.”

I hurriedly tied on the green plug.

His eyes were burning with youthful fire – his step light – old age forgotten as he moved to the quarry’s edge. There was no arthritic hesitation in his arms as he heaved the plug far out into quiet water.

How do old men know such things? I had never heard the term nervous water.

Slowly, I laid my rod down, stepped back and watched my father through tear-rimmed eyes. In anger, I had put away all the good times we shared when I was a boy – hidden them, trying hard to forget in my hatred for him. Now, those times came flooding in as I watched my father.

A heavy, sucking boil erupted as the shad touched the water and suddenly disappeared. My father was into a bass that moved him along the rocks, his frail arms held high, the rod up – tip bent far over – the reel singing as line went out.

The largemouth broke the surface once, twice and then went deep, sulking, testing the mettle of the man, the rod and hook and its own strength. It took awhile, but Dad finally coaxed the fish up, and after a fierce fight with whistling line slicing back and forth through green water in a give-and-take struggle, he called for the net.

Suddenly, the most important thing in my life seemed to dwell around the net and landing that bass for him. I could remember the moment when John had taken the picture by a stream in Oregon of me holding my first trout. Mother was in the photo beside me, both of us grinning at my father. The picture he’d clutched on the plane from Portland.

Dad doubled up his fist and stuck it in the bass’s mouth when we had it on gravel and out of the net. It fit with room to spare.

“What do you think?” he asked, his voice broken, his eyes dancing, a boyish grin on his face.

He was breathing hard, and the doctor in me was worried about that.

“Five pounds easy, Pop . . . closer to seven, though. You better take it easy; we’re over a mile up.”

He eyed me close. “I’m all right. I never caught a fish this big before.”

He lifted the bass and carried it reverently down to the water, supporting it until it slipped away with a slap of its tail into murky green depths. Returning to where I stood, he placed his left hand on my left shoulder and said, “We’ve traded places, haven’t we, son.”

“What do you mean?” He’d called me son.

“It was me that did the tying when we fished until you learned how, remember? It was me on the heavy end of whatever we were moving or doing – me looking after you – worried about you – me giving and you taking. Now it’s your turn.”

“It’s about time, don’t you think?” I said, my eyes dripping tears.

“It feels right,” he said, smiling. “Will your friend let me come here with my son and grandson often?”

“You can count on it. He needs to hear stories of your time, your life, learn what you know – nervous water and other stuff.”

He nodded as he placed his hand over his heart and then moved it to cover my chest over my heart. “It feels good in here,” he said, softly, and then we hugged.

Note: This article originally appeared in the 2013 May/June issue of Sporting Classics magazine.