Editor’s note: This story originally ran as the art column in the January/February 2014 issue of Sporting Classics.

A mother goose leading her goslings across a pond is a passing of generations. A flock of guinea fowl chasing bugs through a garden is a comedy. A bald eagle ending its day is power and regality that needs no gimmicks or exaggeration. A hummingbird taking a moment to survey the garden is a warrior preparing for battle.

No matter where we live, most of us see a variety of birds every day. When we actually take time to notice them, we often see creatures that give us pleasure for many different reasons—as game, as beauty, as the music of dawn. For as far back as he can remember, Stefan Savides has seen birds as works of art.

“My earliest childhood memory, at three years old, was watching my neighbor’s chickens, pecking and running after the things I threw in their pen. That was the beginning of a lifelong fascination with birds. While birds abound everywhere, I made sure I was surrounded by them. I raised, painted, mounted, carved, hunted, nurtured, and sculpted them.”

However you look at it, Stefan took that early captivation with birds and allowed it to dictate his life’s course.

“We are influenced by everything we see,” Stefan says. “Art, nature, our acquaintances. For me, the greatest art influence in my life has been my mother. I give her credit for who I am as an artist.”

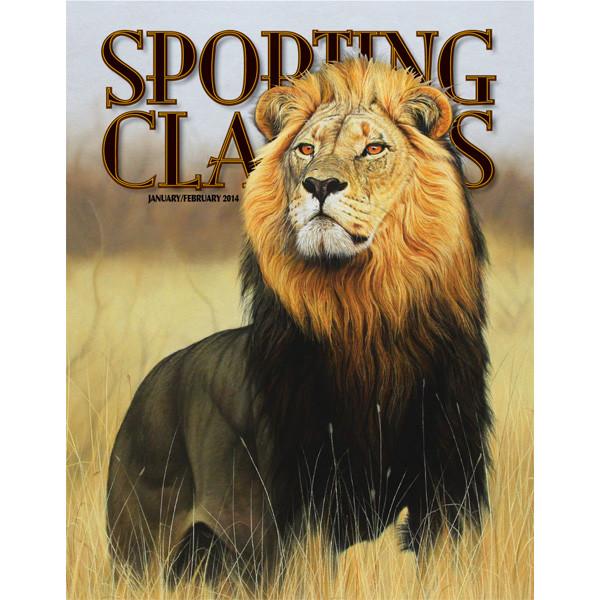

“Rock Star”

Stefan’s mother studied, judged, and competed with floral design, and thus Stefan’s boyhood home was a never-ending parade of three-dimensional art.

“She did everything as an artist. The way she decorated the house or grew the garden or prepared a meal was done with not only an artist’s eye, but an artist’s attention.”

So, like so many children who learn from their parents, Stefan’s life was shaped by what his mother said, but even more by what she did. And she gave him so much more than just an example. She recognized the boy’s nearly fanatical fascination with birds and spent her own time supporting and nurturing it.

“My mother was a gentle woman who steered me away from Cub Scouts because she considered it a precursor to the army. But she didn’t just say no to that endeavor; she took it a step further and became like a den mother of her own junior Audubon Club.”

Stefan’s life never veered from that path. Birds were the one constant running through the rest of his life. By the time he was 12, he was studying taxidermy books and practicing on dead birds his father found along the roadside during his business travels. Because of his mother’s influence, he approached his taxidermy from an artist’s perspective, and he never drifted off course.

“I have never strayed from my childhood fascination with birds,” he says. “I feel totally blessed as my interest in birds has earned me a living, and as a result, I have never worked a day in my life for anyone other than myself.”

He spent most of the next 50 years making his living by recreating avian life in taxidermy. But he did not simply take a pheasant or a wood duck or a pied kingfisher from Africa and reproduce them in fine detail. No, he told their stories in a way that allowed the viewer to understand something deeper about himself or herself. Stefan created Art.

His list of first-place finishes in taxidermy competitions grew, and with them his client list. He traveled to Africa on safari with Dick and Mary Cabela to experience firsthand the birds he would reproduce for their home. He consistently won top awards and recognition for his work. He went on to judge at most of the world’s important taxidermy shows. And he accomplished all the personal and professional goals he set for himself in the taxidermy field.

“Top Gun”

Three-dimensional fine art was the next logical step. For Stefan, it was the only logical step.

“It took me twenty years after I initially thought about bronze sculpture to finally take the plunge,” Stefan says. “But those twenty years didn’t hurt me, as I gained more contacts and grew more as a person and an artist.”

All that time working with real birds gave Stefan an intimate knowledge of their anatomy. Meanwhile, his mother’s artistic passions allowed him to develop an eye for compelling three-dimensional designs.

“I pour everything I know about design and emotion into each piece in hopes that it comes together as a whole to work as art.”

Stefan stayed true to the path he was meant to walk. Often when a tree falls over our individual paths or we stumble on a rocky hill, we try to find some easier way around—it usually takes years, if ever, to rediscover the direction we are supposed to be heading. Stefan has crawled under or over the trees. He has climbed the hills. He has cut through the dense foliage, and though he cannot see the end clearly, he knows he’s right on course.

“Birds are a glimpse into God’s creative genius,” he says. “They may be one of the most varied creatures on earth. You find them everywhere—in forests, deserts, swamps, even polar regions and oceans. Each species has an essence you can only begin to understand by spending time with it. My goal as a sculptor is to capture their essence without the use of color and detail, which is really not easy for a ‘recovering taxidermist.’”

Stefan’s work has quickly gained the respect and recognition of art connoisseurs, collectors, and peers. So much so that renowned painter John Banovich has invited Stefan

to display his work alongside his own at many of the most celebrated outdoor expos—that kind of compliment is beyond words.

Stefan Savides is one of those rare people who has been able to tap into the most pure purpose of art and of life itself—by simply being who and what he was meant to be.