Harold Martin captured the true essence of the autumn rutting season as he went on to say, “When the mast is heavy the deer will stay fat and sleek all winter on the acorns, and the bear, who are his friends, will lie cradled in rolls of fat, and the wild hogs will have some meat on their ribs, and all of the people of the woods will come into spring fat and sassy.

“. . . A heavy mast means that when spring clothes the hills in green again, the fawns will be strong and healthy and nimble on their thin legs as they flash their little flags from the windfalls and the streams. And the yearling bucks will be husky and strong as they grow into spike-horn stags.”

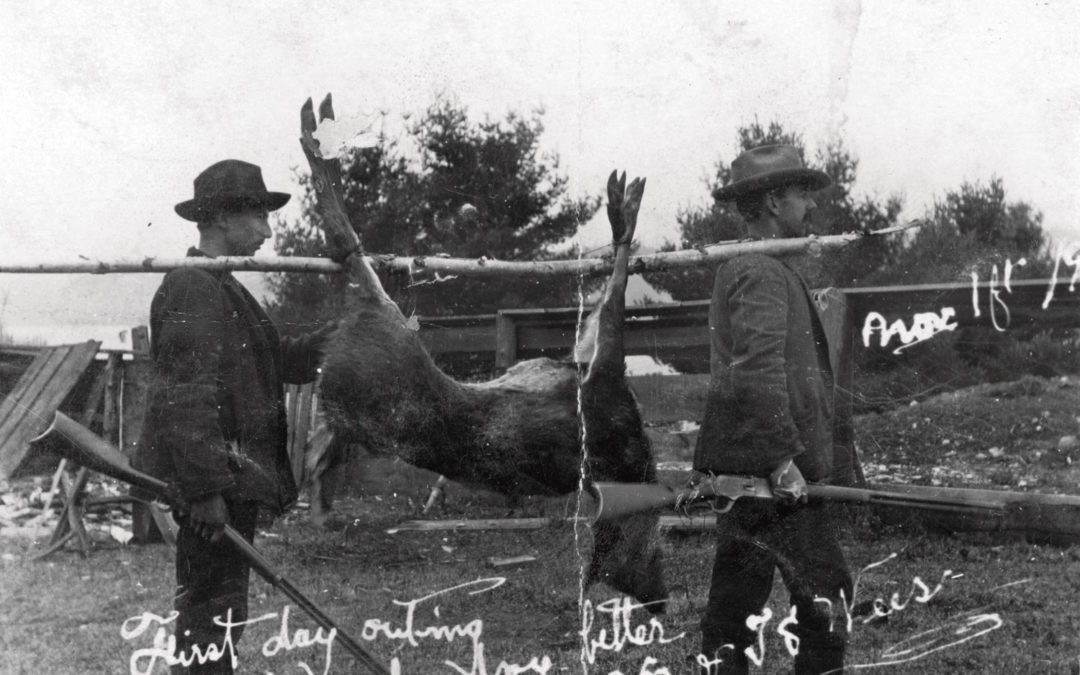

North Country Giants

Lots of Winchesters and a Marlin or two were responsible for several crackerjack bucks and one small bear cub, probably taken in northern Minnesota or Wisconsin. Most of these men are likely recent immigrants whose families made their way to the Midwest and began the respected tradition of hunting together each November. Photo circa 1905.

Come fall, those spike-horn stags will be feeling their oats. They may stay out of the way of the big boys, and they don’t quite know what to do with their bulging muscles and raging hormones, but they learn quickly enough and they try to act out the part in every way—making scrapes, thrashing shrubs with their tiny antlers, chasing and irritating does, engaging in pushing and shoving contests with other yearlings and, in general, trying to be the bad boys of the neighborhood.

Since times immemorial, hunters have known the rutting season is the best time to be in the woods. The term, “the Moon of the Rutting Stag” comes directly from the Cherokee Indians. If the mast was unusually good, those thick-necked bucks seemingly had limitless energy as they searched the woods for receptive does. This was one of the few times when a crafty old mossback was apt to slip up and get caught an hour after daylight as he searched the woods for a mate. And in his zeal to corner an elusive doe, a buck might let down his guard and present a shot to a patient hunter.

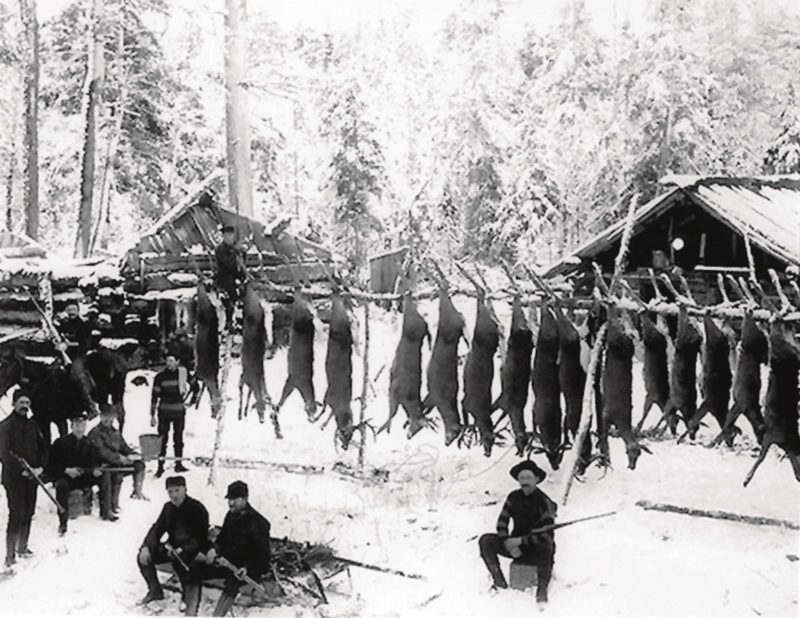

The Glory Days

These large-bodied bucks were probably taken during the rutting season at an upscale hunting lodge in the Adirondacks or northern Maine and were probably the result of a week’s hunt. Meat poles like this were not uncommon at many hunting establishments in the early 1900s. Wonder if this contented hunter knows how fortunate he is to be living amidst such whitetail abundance… As he looks over the mountain of outstanding bucks, among them a young moose, he appears to be holding a Winchester Model 1894 rifle with a half-round, half-octagon barrel, probably made around 1905. Photo circa 1910.

In his 1972 book The Whitetail Deer Guide, author Ken Heuser wrote, “When you see a buck traveling along with his nose to the ground and his tail straight out back, he’s trailing a doe. This is the time a buck can get so excited he will hop stiff legged, looking at the brush and grunting at every hop. His eyes will become glassy and often he will stand with his hindquarters sagging. The buck’s odor becomes very strong at this time. A trained human nose will pick it up at quite a distance. I have smelled them at close to 100 yards away when I was downwind. The strong odor comes from the buck’s metatarsal glands and from his wallowing in his scrape. Occasionally a buck will get so excited he will rub his shoulders in the mud of the scrape until they are well coated. It doesn’t take too long before the old boy smells worse than the elephant pit at the zoo.”

Few hunters of yesteryear specifically hunted the rut or targeted individual bucks, but they certainly recognized the unmistakable smell of musk. And just like it does today, that rank smell that sometimes lingered in the wet morning woods got their blood “to boiling.” Most turn-of-the-century hunters engaged in some type of group hunting. Some were still-hunters and some were stand-hunters, but as a general rule, even lone hunters were opportunists who shot whatever they saw—buck or doe—while tracking or waiting patiently for whatever might happen by the stump they were sitting on.

Deer Hunter’s Valhalla

It’s really not Viking heaven, but some of these hardy men might be related to Vikings. Several beautiful bucks hang on the meat pole in this sprawling camp. It appears as though the moon of the rutting stag has been very good to these diehard deer slayers. Lots of Winchester repeaters and at least one Savage ’99 helped bring down this outlandish supply of venison. Photo circa 1906.

The majority of hunters were well aware of the breeding season, but few considered it as the best time to shoot a buck. Most vintage hunters viewed cold weather and snow as the driving motivations for getting out in the woods, but the sight of a buck chasing a doe was always exhilarating. And since most hunting seasons occurred in November, the Moon of the Rutting Stag was always a magical time.

Dobie’s Dawn of American Deer Hunting hardcover book is filled with stories of “the good ol’ days” of whitetail hunting, and tons of black and white photos of the hunters and their prize.

Order your signed copy of Duncan Dobie’s Dawn of American Deer Hunting Volume 2 and 3– a photographic Odyssey of whitetail hunting at sportingclassicsstore.com.