The decline of Montana’s rivers foretells a new battle brewing between businesses that depend on fishing tourism and the state’s ranchers.

I’ll never forget the first time I met the Big Hole River. The relationship started on one of those crisp Montana autumn days, cobalt blue skies with the cottonwoods dressed in lemon sequins, shimmering in the sunlight letting a fly fisherman know that it was ready to dance. If you’ve ever driven past this river in late September and early October, you know just how irresistible it can be, seductive really.

I waded to a riffle that ran in the late afternoon shadow of a cut bank, willows partly shielding it from sight of ospreys. I dropped a hopper at the top of the short run, not needing to mend my line for 20 feet or maybe a bit more. Perhaps two seconds into the drift, the fly disappeared with hardly a disturbance on the surface, as if it simply passed into a parallel universe through some undetectable worm hole. I clenched the line in what amounted to a simple reflex at the fly’s vanishing. Then my rod bent hard and fast as a still unseen fish was protesting its way down river, seemingly looking to make off with the purse it just snatched. In that moment, I pictured the scene as a passing eagle might, as Shilstone might have painted it. It was an out of body moment that I had never experienced fishing before or since. The Big Hole had whispered in my ear…that it was time to come home to her waters.

That began a series of restless days and nights…months and years, really. That’s the way many of us come to Montana, for the journey often starts in the spirit before we’re moved to find a place to call home. With enough money saved and my wife convinced that it would be okay to share me with the river, we built a place in our piece of Montana along the banks of the Big Hole where I could draw strength from her life force each day I was there.

My sons became fishermen and river keepers on this water, mostly thanks to friends and guides named George, Eric, Ryan, Rick and several others who cared enough to teach along the way. They saw in my twins the same wonder and awe they knew at that age, the intrigue and curiosity in how it all worked from the fly to the fish to the hope of more to come.

We shared the Big Hole with so many friends as well, in many cases people who came from faraway lands and cities, people who had heard of Montana but didn’t know that it was a state of mind until they arrived. Baptizing souls to this river became one of the great joys of my life, for people who spent a day on the river returned to our home renewed, understanding the draw of these currents and just how endearing they could be.

Then something changed.

The river became stingy, seldom sharing the numbers of fish she once did. Drifts that used to produce 30 or more fish—a mix of rainbows, browns, the occasional brook trout and grayling—now delivered less than a dozen. While we used to count on a few fish over 18 inches each time we floated, few made it past 14 anymore…some floats never saw more than a ruler’s length trout, if any at all. Before we knew it, we were counting white fish in our daily totals.

That’s when I began to notice what was happening. How could I have been so oblivious to what the Big Hole was enduring, I began to think to myself. Trees were being cut along its shores, the banks and the brush that help protect favorite trout lairs were being burned for no more reason than to meet the vision of someone’s river aesthetic, as if the Big Hole wasn’t already perfect in its natural form. A little nip-tuck here and there that is seldom noticed until the river is no longer recognizable, until the trout homes were gone or abandoned under a layer of silt.

Then came the lust for a third crop of hay. Fly the Big Hole Valley in the hot, often dry days of August and an Incan like series of sprinklers and irrigation canals bleed the Big Hole daily, siphoning water levels so low that there is no longer enough oxygen to support trout. The state’s answer for this is to stop angling to reduce stress on the fish, as if the way to cure the disease is to treat the symptom, not the cause.

The Big Hole River, like many trout streams throughout Montana, has been impacted by hay irrigation that often lowers the water and reduces oxygen levels to the point of stressing fish. Photo by Chris Dorsey, Dorsey Pictures

As any honest rancher will tell you, the third crop of hay is the weakest, sometimes not worth the time and energy, to say nothing of water, to grow it. If the river could speak, however, it would ask what of the anglers who come to Montana to meet its fish? Fishermen spend nearly $1 billion annually here, fueling the entire rural economy that includes restaurants, gas stations, sport shops, grocery stores, bars, guides and outfitters, lodges and scores of other enterprises. To suggest that this is only a debate between ranching and fishing, which is a common refrain, is to say that the fight is only about the golden egg, not the goose that laid it and all who profit from it.

Furthermore, cattle and hay ranching employs few people in Montana as most operations are run by a small number of individuals who now ride machines instead of horses. Cattle processing, for the most part, is done out of state, in places like Nebraska and Iowa, so Montana doesn’t even benefit from the jobs created by its own beef production.

I do not believe any of this is an orchestrated, sinister plot to rob the Big Hole and other Montana rivers of their treasures, however. I do not think ranchers are evil people intent on killing every fish in the river so that they never have to hear the complaints of anglers and guides. Rather, there is simply more demand than ever to extract dollars out of each acre of ground and anyone and anything—like anglers and trout—that get in the way of that mission become an opponent…needlessly.

While there have been county watershed boards and other groups formed to bring a dialogue between disparate factions, most of these organizations are run by ranchers and ranching interests, and the best outcomes are to try and get ranchers to voluntarily decrease their use of river water for the last crop of hay. It’s a public face—some would say farce—to ameliorate contention between ranching and fishing interests.

The outcomes, however, are dubious at best, for many ranchers simply disregard such agreements and open their irrigation head gates to the river—often in the cover of darkness—dropping the Big Hole significantly overnight. Thus, the amount of oxygen needed to support trout, and the extended human community around them, declines to the point of killing fish. Rivers don’t die overnight and there are no obituaries. Instead, it’s a cancerous end as a river chokes and the big fish die one by one, their corpses absorbed by crayfish and other lesser organisms that remove the evidence.

Businesses throughout Montana depend on visiting anglers who pump hundreds of millions of dollars into the state’s economy each year. – Photo by Chris Dorsey, Dorsey Pictures

How could this be, you ask? What about federal laws to protect such shared resources? Those are questions more Montanans are asking as well, for the federal Environmental Protection Agency and provisions of the Clean Water Act are in place for just such a backstop. It’s the responsibility of Montana’s Department of Environmental Quality to enforce those laws, so why aren’t they doing their job? Why isn’t the legislature demanding that they fulfill their responsibilities? A loss of dissolved oxygen is degrading the Big Hole’s water quality and the same problem exists across many of the state’s rivers as fishing is often closed in late summer. Those outcomes are especially painful to the thousands of Montanans whose livelihoods depend on anglers.

Big Hole River guides walk a fine line, for they are selling a product—epic fishing on one of America’s last great freestone (no dams) rivers. Who could blame them for not publicly decrying the state of affairs, for to do so is an admission that the fishery, and their offering, is in decline. How can they pay for their rod days without a steady stream of clients? Too, there are always images of plenty of fish that show up in that bastion of truth and clarity known as social media to proclaim the river still the deliverer of fishing dreams. Anyone who has spent consistent time on the Big Hole, however, can separate marketing from reality.

Someday, perhaps, the anglers, guides and the many businesses supported by fishermen will take their rightful place at the head of the table of Montana’s river interests. For now, however, the Montana that once was—a state that had become the spiritual center of the fly fishing universe, brimming with unmatched numbers of trout and angling opportunities—is no longer. Instead, the promise of the Big Hole and other rivers to deliver historic days on the water—the kind that echo through America’s fishing community—are mostly just memories, like ghosts of fishermen past.

This article originally appeared in Forbes. Follow Sporting Classics TV host Chris Dorsey at Forbes.

To learn more about the Montana River Wars, listen to this episode of the Sporting Classics Podcast with Chris Dorsey:

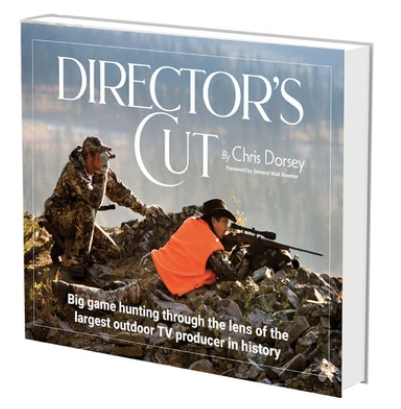

The World Of Sporting Literature Has A New Classic from one of the planet’s most widely traveled hunters. Director’s Cut…Big game hunting through the lens of the largest outdoor TV producer in history, is a book and film production more than 15 years in the making. Author and Executive Producer Chris Dorsey, along with a team of the world’s best sporting life photographers and cinematographers, embarked on expeditions to distant corners of the globe to create an indelible portrait of big game hunting.

The World Of Sporting Literature Has A New Classic from one of the planet’s most widely traveled hunters. Director’s Cut…Big game hunting through the lens of the largest outdoor TV producer in history, is a book and film production more than 15 years in the making. Author and Executive Producer Chris Dorsey, along with a team of the world’s best sporting life photographers and cinematographers, embarked on expeditions to distant corners of the globe to create an indelible portrait of big game hunting.

Dorsey has spent the past 25 years investigating and chronicling the animals, people and unforgettable places home to remarkable big game hunts while producing nearly 60 outdoor adventure television series. In the process, his teams amassed a library of more than 100,000 hours of HD footage and nearly 150,000 photographs, making Director’s Cut (the book and DVD) an unmatched celebration of the world of big game hunting. Buy Now