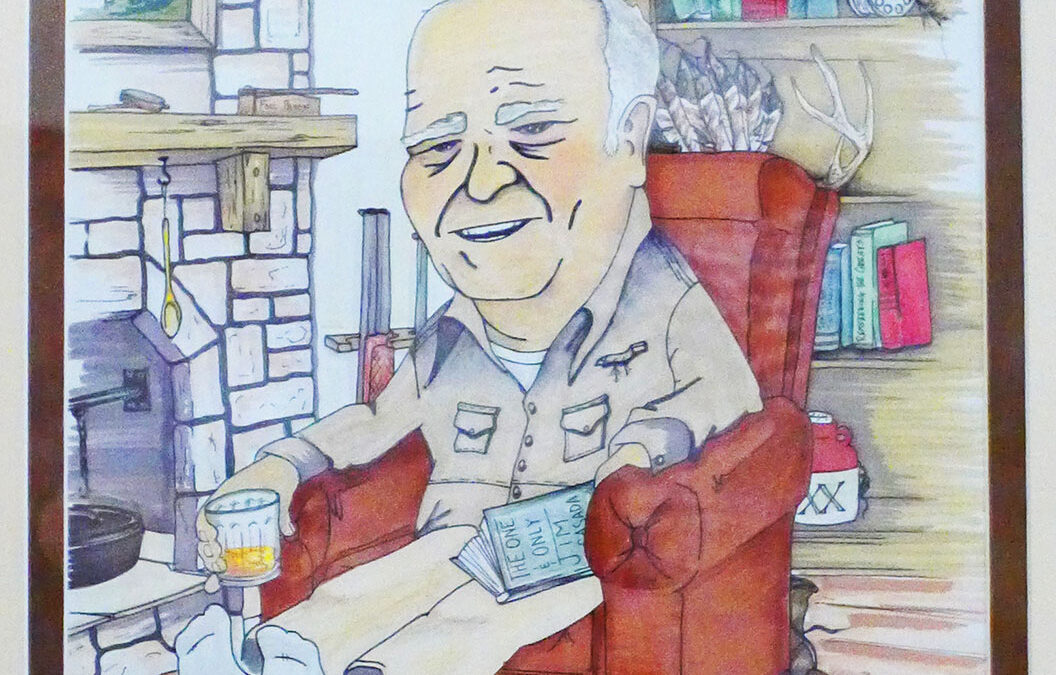

The first installment in Jim Casada’s new series: THE MISADVENTURES OF MOLLYGRUBS MESSER

The parents of the newborn lad who would in time be known to one and all as Mollygrubs Messer most assuredly did not dub their offspring “Mollygrubs,” a quaint word widely used in the Southern Appalachians of the boy’s birth to describe a state of depression or despair. Indeed, in a moment of what some of their neighbors and kinfolk variously described as “getting too big for their britches” or “above their raising,” the proud couple named what would prove to be their only child W. McGillahaney Messer. The “W” didn’t stand for anything, although years later more than one wag would suggest it was short for “Worthless,” while McGillahaney was a singularly ill-fated attempt to endow the infant lad with an aura of importance.

All parental efforts at elitism notwithstanding, by the time the rather chubby, good-natured but extraordinarily gullible youngster entered grade school his lot in life had already been cast. Or at any rate the moniker that would dog his footsteps through the years in much the same fashion that a dark cloud always hovered over the head of cartoonist Al Capps’ forlorn figure in the “Li’l Abner” comic strip, Joe Btfsplk, was firmly in place. An old codger in the little town where the boy grew up, having observed his bumbling, fumbling ways for some time, pithily opined: “That young fella’s just a mobile case of the mollygrubs.” The moniker stuck as if divinely ordained.

Undoubtedly some of the problems lay with his doting parents. His mother thought her offspring should be a reincarnation of Little Lord Fauntleroy with interests in ballet, playing the piano, fine art, and the like. His father, to the contrary, envisioned the boy as a budding sportsman combining the finer traits of Daniel Boone, the Mountain Men, great African hunter-explorers, and Theodore Roosevelt. Thus the lad was tossed and turned, almost from the cradle, between two dramatically different worlds. Small wonder everyone called him Mollygrubs.

One of his first major misadventures came as a result of membership in the Boy Scouts. His father enrolled him in that venerable organization with the best of intentions, but unfortunately by that time his mother’s mollycoddling interference in his development had already made him something of a whipping post for the often crude and sometimes cruel attention of boys his age. They picked on the chubby boy, made him the victim of jokes without end, and generally laced his life with misery.

Such was the background to an overnight summer outing his Scout troop took in the sprawling Great Smoky Mountains National Park near where he lived. The purpose of the backwoods adventure was to acquire some basic camping and woodcraft skills amidst the one-time haunts of famed woodsman Horace Kephart, bond around campfire settings in the great outdoors, do a bit of trout fishing, and gain useful knowledge of the region’s great abundance of plant life. It was in the latter arena that Mollygrubs went badly astray.

The scoutmaster, a genial soul with many years of experience in training boys and introducing them to the wonders of the wilds and closeness to the good earth, spent the first two evenings around the campfire offering instruction on utilizing the natural world to good advantage. He talked about foraging for edibles, how to make a serviceable basket from birch bark, and what to do should one get lost. Little knowing what would transpire, he even touched on the most basic of matters–proper disposal of human waste and how, in times of necessity, broad leaves such as those found on pawpaws or poplars could be used as ersatz toilet paper.

Mollygrubs absorbed this information with all the intensity typical of a tyro, and on a morning hike the third day of the outing, he had an unexpected and sudden opportunity to put some of his newly acquired knowledge into practice. Camp diet to that point had been long on fried foods such as onions, potatoes, eggs, bacon, and Spam and woefully short on fiber. Matters were likely worsened by over-indulgence in the wrong source of fiber the previous afternoon. The whole troop had feasted on under-ripe apples they came across in a long abandoned orchard. The result was that Mollygrubs, whose weight problems and dietary preferences hadn’t endowed him with the strongest of digestive systems, experienced a particularly virulent onset of what was locally known as the “green apple trots.”

When a pressing urge hit him while the troop was on a day-long hike, he had two unwelcome choices. Take to the woods and drop trousers in rapid-fire fashion or else forthwith befoul said trousers. He wisely chose the first option, although what ensued doubtless left him wishing he had messed his pants and endured all the verbal abuse his comrades would have heaped on him in the aftermath.

As it was, he left the trail, found a suitable spot, and achieved instantaneous relief albeit it proved decidedly temporary. Remembering the scoutmaster’s lesson from the previous evening, Mollygrubs was most grateful when he spied a vine, liberally adorned with shiny leaves, grouped in threes and pointed at the end, climbing up a nearby oak tree. He immediately availed himself of an ample supply of the convenient leaves, cleaned up, and rejoined his comrades.

All seemed well for a few hours, but then what began as an itch in Mollygrubs’ nether regions rapidly progressed to sheer agony. By the time the day was over and the young Scout was back home, he was sufficiently miserable, never mind the location of his suffering, to complain to his mother. After an inspection she forthwith rushed her pampered son to the local hospital’s emergency room. There the physician on duty struggled mightily, and with less than complete success, to avoid chuckling as he obtained the details of just how his patient had acquired what was quite possibly the worst case of poison ivy rash he had ever seen.

Ten days and three cortisone shots later, supplemented by a daily regimen of cortisone pills and a seeming ocean of Calamine Lotion, Mollygrubs was once more reasonably close to normal. His first serious effort to get back to nature had resulted in three things — a sorely afflicted back end, becoming the butt of many a joke, and an early chapter in what would be a lifetime of outdoors misadventures.

He endured his humiliation in reasonably good stead, having already become somewhat inured to being a sort of walking piñata constantly assailed by verbal sticks and stones. Such, however, was not the case with his overly protective mother. Far from realizing that her spoiled son could benefit from appreciably less “mother henning” and a great deal more learning from the slings and arrows of misfortune, over the coming years she persisted in meddling in everything from the smallest of matters in Mollygrubs’ daily life to the uncertainties and timidity associated with teenage years and raging testosterone. Her shenanigans in connection with the annual Juniors for Conservation banquet and dance were a prime example, and in the next of many misadventures stretching through the hapless fellow’s youth and beyond, we’ll take a peek at the disastrous intrusion of Mrs. Karen Messer into manners of romance in her son’s life.

Fishing for Chickens is a well-seasoned blend of memoir and cookbook. It offers the perspective of a Bryson City, North Carolina, native on a particular portion of southern Appalachia―the Smokies. Casada serves up a detailed description of the folkways of food as they existed in the Smokies over a span of three generations, beginning early in the twentieth century. Fancy-dancy food magazines and self-ordained cuisine cognoscenti regularly rave about gustatory delights reflecting the Appalachian cooking tradition. Yet they focus on restaurants in regional cities such as Asheville and Nashville, Chattanooga and Cleveland, or even the bustling metropolis of Atlanta. Simply put, they are missing the boat, at least in Casada’s eyes. Peppered with ample anecdotes, personal memories and experiences, the wisdom of wonderful cooks, and recipes reflective of the overall high-country culinary experience, Casada’s book brings these culinary tales to life. Buy Now

Fishing for Chickens is a well-seasoned blend of memoir and cookbook. It offers the perspective of a Bryson City, North Carolina, native on a particular portion of southern Appalachia―the Smokies. Casada serves up a detailed description of the folkways of food as they existed in the Smokies over a span of three generations, beginning early in the twentieth century. Fancy-dancy food magazines and self-ordained cuisine cognoscenti regularly rave about gustatory delights reflecting the Appalachian cooking tradition. Yet they focus on restaurants in regional cities such as Asheville and Nashville, Chattanooga and Cleveland, or even the bustling metropolis of Atlanta. Simply put, they are missing the boat, at least in Casada’s eyes. Peppered with ample anecdotes, personal memories and experiences, the wisdom of wonderful cooks, and recipes reflective of the overall high-country culinary experience, Casada’s book brings these culinary tales to life. Buy Now