Mick Doellinger’s climb as a wildlife sculptor has been based on pure outback adventure.

Mick Doellinger may live in Texas, but his accent carries the twang of a regional burr that’s actually from a continent halfway around the world. Hailed as a rising star in contemporary wildlife art, Doellinger claims a path to prominence no other animal sculptor has taken.

“He’s led an interesting life, that’s for sure,” says Martin F. “Bubba” Wood, a dean of American sporting art and the longtime proprietor of Collector’s Covey Fine Art Gallery in Dallas. “Mick’s one of those nice, mild-mannered guys you meet, but then your jaw drops when you hear of the places he’s been and how astute he is about art. But it’s his work that really stands out.”

Born in Germany in 1956, Doellinger is the son of parents who emigrated from Europe to Australia. A former rodeo cowboy, he once wrestled steers and rode bucking bulls. Known for his sophisticated approach to the animal form, he perfected his feel for animal anatomy and mass by boning out thousands of domestic sheep, kangaroos, and Asiatic water buffalo in meatpacking plants.

Doellinger has an enigmatic résumé, but one might never know it by his unassuming personality. Instead, he makes potent first impressions through his classical portrayals of African and North American subjects, noted for their nuanced, polished patinas. You gaze upon them and believe you understand the essence of the man.

When Doellinger and I spoke recently, he was back in his studio along Lake Weatherford west of Fort Worth. Outside, whitetail bucks were sparring in the rut. Doellinger and his wife, Katrina, had just returned from a “research trip” stalking moose and hiking through the brown bear-dense mountains of the Canadian Yukon. On his sculpting table was a Cape buffalo and the maquette of a bison soon bound for the foundry. Bubba Wood, who dropped by earlier, told me he was certain Doellinger’s buffalo piece would sell out just as quickly as two earlier bronze editions depicting the great, surly beasts.

Doellinger’s instincts with form are impressionistic; he admires how Rembrandt Bugatti (1884-1916) and Paolo Troubetzkoy (1866-1938) communicated the spirit of their subjects—Bugatti as one of the famed 19th century animaliers following in the footsteps of Antoine-Louis Barye and the Russian-Italian Troubetzkoy with human figures.

“There are many great contemporary sculptors I admire in the U.S. today, as there are in the UK,” says Doellinger. “Some are loose, others tight, along with those who tend to work more abstractly. Like them, I have no desire to make little literal replicas. I want to touch the emotions of the viewer.”

He recalls encountering Joseph Edgar Boehm’s public monument outside the State Library of Victoria in Melbourne, depicting the martyr St. George on horseback slaying the mythological dragon.

“I stood in awe.”

Agitated

One of Doellinger’s early mentors was the Melbourne-based sculptor William Ricketts (1898-1993), known for his terra-cotta celebrations of aboriginal people. He was introduced to Ricketts at age 11.

“He showed me some things, gave me a block of clay, which I fashioned into a composition, and then he fired it for me. To have affirmation so young and from someone like him was hugely reinforcing,” he says.

Shining through Doellinger’s portfolio, reflecting the ethic taught to him by Ricketts, is a deep sense of relatedness and empathy for his subjects.

“I don’t know if everyone is the same growing up, but as a child I would pretend to be animals crawling on all fours across the ground,” Doellinger says. “In my head now, I do the same thing to understand its personality, lightness, and speed of movement, be it a dog, bear, elephant, or lion. I want their gestures to say something; I want them to have impact and weight.”

At 15 Doellinger started competing in rodeos and tasted some success in rough stock events. Seven years later, in 1979, he made his first trip to the U.S., spending time in the Central Valley of California partaking in steer wrestling.

“Fortunately, I didn’t get beat up too bad,” he says.

On the side, he fell into the company of taxidermists, which whetted his interest in bringing three dimensions to creatures he had grown up sketching in Australia.

“When I was in my teen years, having a career as a fine artist didn’t seem to be in the realm of possibility. I just wanted to be a cowboy in the Outback,” he says, noting that wranglers in Australia are known as “ringers” and Doellinger loved being in the saddle. From there, he took a job as a meat shooter for pet-food companies in the sparsely populated Northern Territory, domain of the fictional Crocodile Dundee. The Kimberly Coast is home to the longest tropical wilderness coastline in the world.

“It’s an environment where you have to have your wits,” he says.

The territory is made up of many large ranches millions of acres in size. It was a time in which the government implemented a massive depopulation program to eradicate brucellosis and tuberculosis in cattle.

While exploring the Outback he harvested Asiatic buffalo and feral cattle. Later he found work in meatpacking plants, boning out sheep, cows, and kangaroos in facilities where he was paid per animal, not by the hour.

“Michelangelo worked in cadavers. I got employed at a slaughterhouse. They’d pay us sixty cents each, and we’d do thirty animals an hour. I would take the bones out of forty thousand to fifty thousand sheep or kangaroos a year.”

Echoing the maxim that it takes 10,000 hours of practice before a skillset is mastered, Doellinger’s hands-on grunt work imprinted a keen understanding of animal physiology and musculature that lies beneath the outer carriage of large quadrupeds. He completed hundreds of thousands of dissections that laid the foundation for his work in taxidermy. In the years after the start of the new millennium, he returned to the U.S. and lived in Texas, where he completed big-game mounts for an assortment of clients who praised him for his command of animal gesture.

“My philosophy is to sculpt from the inside out,” he says. “What you express on the surface is a product of how much you know about what lies beneath, the mechanics that create locomotion.”

Brute Force

Doellinger was commissioned to create a monument-sized bronze of a leaping whitetail for a shopping mall, and his reputation quickly spread by word of mouth. He also received a prestigious assignment to sculpt an eight-foot tribute to University of Houston football coach Bill Yeoman.

In 2006 he began an official association with Collector’s Covey Gallery, and then Fama Fine Art.

“I told Mick that the chance someone with his level of talent would walk in cold off the street was unbelievable,” Wood told me. “In my nearly fifty years of dealing art, Mick, given what I’ve witnessed with the evolution and maturity of his style, ranks as one of my highlights in forging relationships with artists.”

Not prolific compared to some of his contemporaries, Doellinger only completes about four pieces annually. He is intimately involved in all of the stages of production, including doing his own patinas.

With “Curiosity,” a cougar stands provocatively on his haunches, engaging our attention and leaving us with wonder. In “Dune Runner,” an oryx strikes a stately pose that might have been captured during Greco-Roman times. And with “Totem,” a bust of a bison head, Doellinger conveys the majesty of America’s greatest prairie icon.

“In the last few years, Mick has become one of the most collected of all the wildlife sculptors,” says Alan Fama, owner of Fama Fine Art in Houston. “Beyond question, he’s doing his best work, getting the critical recognition he deserves and winning awards.”

Fama ticks off a list of varied subjects, each one meeting with enthusiasm from collectors. There are the rhino, Cape buffalo, and elephant pieces, the longhorn compositions, and portrayals of big game and hunting dogs.

Doellinger reckons his strongest following resides in Texas because “it probably has a concentration of more hunters per capita than any other place I can think of.” When it comes to appreciating wildlife, the tastes there are cosmopolitan.

Nothing substitutes, Doellinger says, for real-life experiences like his research excursions to Africa, where he’s been able to handle live animals and field-dress others.

When I asked Professional Hunter Robin Hurt, the renowned purveyor of sporting and photographic safaris based in Windhoek, Namibia, what makes Doellinger’s fine art so appealing to him, Hurt didn’t hesitate.

“The lifelikeness of his subject that captures the spirit and character of the animal itself,” he explains. “In particular, I was attracted to and most impressed by his black rhino sculpture ‘Brute Force.’ It totally captured the temperament and spirit of this most dangerous, and yet most endangered, animal.”

“Every species I’ve ever sculpted, I’ve touched and tried to feel where its life force comes from,” Doellinger says, noting that when he had contact with a rhino at a special protection facility it was like touching a dinosaur. Today, with the future of so many species uncertain in the world, he hopes his art will inspire people to remember and do what they can to keep them alive. When art does its job, he notes, it makes us conscious.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the January/February 2017 issue of Sporting Classics.

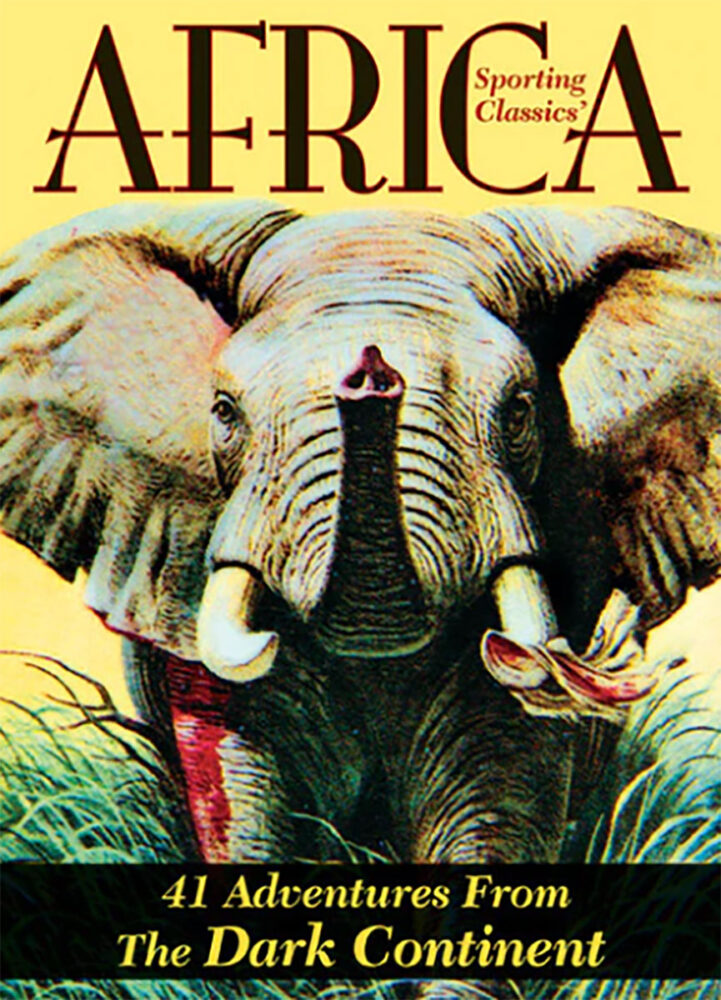

Featuring over 50 illustrations by world-renowned artist Bob Kuhn, AFRICA features more than 400 pages of unforgettable stories by some of the finest professional hunters and writers of sporting adventure.

Featuring over 50 illustrations by world-renowned artist Bob Kuhn, AFRICA features more than 400 pages of unforgettable stories by some of the finest professional hunters and writers of sporting adventure.

Over the past three decades Sporting Classics has published more than 100 articles and columns on sport and wildlife conservation in Africa. This anthology, which commemorates the magazine’s 30th anniversary, features the best of those stories. Many talented, dedicated people made this book possible, particularly the authors who eagerly shared their stories. Buy Now