It is up to the next generation of dedicated conservation hunters to protect, enhance and defend America’s millions of acres of public land.

Richard stood five feet, two inches and wrestled. He wrestled on the mat in college, wrestled steer carcasses from the cooler to the cutting blocks in Dad’s butcher shop. He’d let us kids hit his stomach as hard as we could. And on Saturdays in October he’d take us hunting.

“Keep those guns unloaded until we’re over the fence. And watch those muzzles or you’re sitting in the car ’til we’re done.”

He’d broken both arms as a kid and they’d healed permanently bent. Made him look muscle bound. Didn’t hinder his shooting. “Stop. Quiet. Now listen.”

We were crashing our way through a bulrush thicket, our boots squishing mud, noses tickling cattail fluff, wishing we had a big Lab to sniff out the pheasants. Turned out we didn’t need one. After a minute of silence, we heard the rustle. Richard charged at it like a madman. Rooster up!

Wham!

Rooster down. We pulled a plastic wad from its back. Richard was quick. And just like that he’d taught us how to hunt pheasants with our ears.

Rhett is more steady than quick. Nerves of steel or maybe none at all. Doesn’t get rattled. Doesn’t quiver, let alone shake, never mind he’s just hunched and crawled a half mile to get in range of the first buck of his life.

“If the sights are steady on his shoulder, you can shoot.” He does. The rifle goes click. But doesn’t move.

“It didn’t go off,” the 12-year-old whispers, head still on the stock. Cool.

“That’s because we didn’t put a cartridge in. You want to?” He did.

“Now this time I want you to aim with the horizontal line of the scope just under his backline. At this range the bullet will drop, fall right into the heart. Rhett chambers, steadies rifle on pack, waits until the foraging deer holds broadside, shoots. Heart shot. Three hundred twenty yards. Rhett’s first lesson in ballistics.

Spomer had the honor of mentoring two teens through four seasons.

Rhett’s older brother, Mitchell, got similar lessons with similar results. Guiding them to deer proved more fulfilling than any of my own kills. I had the honor of mentoring these two teens through four seasons. They are my good friends’ grandkids. Their father takes them hunting when he can, but he’s often working to keep the home fires burning, as so many fathers must.

Neither Rhett nor Mitchell know they owe Richard a note of thanks. But that’s OK because Richard probably never thanked the man who’d inspired the man who taught Richard to shoot and hunt. So I will. Thank you to all the hunters who’ve taken a kid under their wing and passed on our treasured traditions.

Our hunter’s world is entwined in a long line of mentors and proteges, many unaware of their significance any more than we’re aware of the grandmothers who showed our mothers how to convert sour rhubarb into sweet pie, of grandfathers who taught Dad to skin a hog, change the oil, fix a fence. For millennia we just got on with life, doing what needed doing, picking up what we needed to know as naturally as we learned to run, swim, fish.

These days it seems we’re so preoccupied keeping kids preoccupied we leave no time for them to absorb the ways of life, the machinations of food and hearth. Then again, few adults have the knowledge or skills for that, either. We’ve sacrificed the can-do for the can-pay way of life. Outsourced living. Soccer and ballet are fun and healthful exercise, but not life skills.

But we can’t outsource hunting. This most ancient of human enterprises must be done, not simulated. Regardless the numbers of ranchers and cattle, a work stoppage at the packing plant means no burgers and hotdogs for the next soccer match. If we want to save hunting, we must start mentoring.

Proof in support of this are new positions opening at Fish & Game agencies across the country. Retention and Recruitment Officers. F&G knows who butters its bread, and it isn’t PETA. Without hunters, no license sales. Without license sales, no game wardens, biologists, disease research, species reintroductions….

Yada yada yada. We’ve heard it all before. But we don’t advertise it enough. Who knows that hunter-imposed excise taxes on guns and ammo in 1937 has pumped $19 billion into wildlife programs? License and tag sales have added billions more for wetlands, grasslands, forests, species reintroductions and restoration. We’ve produced more elk, pronghorns, sheep, bears, ducks, turkeys, geese, falcons, eagles, cranes, Kirtland warblers — you didn’t think HSUS and PETA membership fees were paying for any of this, did you?

Unfortunately, but inevitably, the men and women who built our wildlife legacy are leaving it. And coming up behind us are computer gamers, skateboarders, soccer players, movie buffs.

Heck, I don’t know half of what kids do these days, but hunting isn’t much of it. Because hunting is denigrated, not celebrated, in pop culture. Disney doesn’t make movies about Davey Crockett and Dan’l Boone anymore. No one writes pop tunes about gun toting folk heroes dressed in biodegradable furs.

So we have to be the unlikely “heroes.” That old man with the dog and shotgun. That old lady who, rumor has it, actually sneaks through the woods, shoots squirrels, skins ’em and eats them! Heck, we can even be that groomed, white-collar accountant who loads a clean, undented, recent model 4×4 truck with tents, camp stoves, cots and coolers to spend a week in the mountains bugling at elk. Mentors don’t have to be crusty curmudgeons.

Start with stories. Short. Pithy. Perhaps a hint of mystery. Get the kids interested, asking questions. “Did you really sleep on the ground? All night? Without a tent or anything?” Feed them bits and pieces. And then just show them what you know. Humbly. Honestly. But with the honest passion you feel for all the wonders that are our hunting world.

Here in the U.S.A. we have something called public land. Millions and millions of acres of it. And that is what we must protect, enhance and defend. And the next generation of dedicated conservation hunters must do it. Know any?

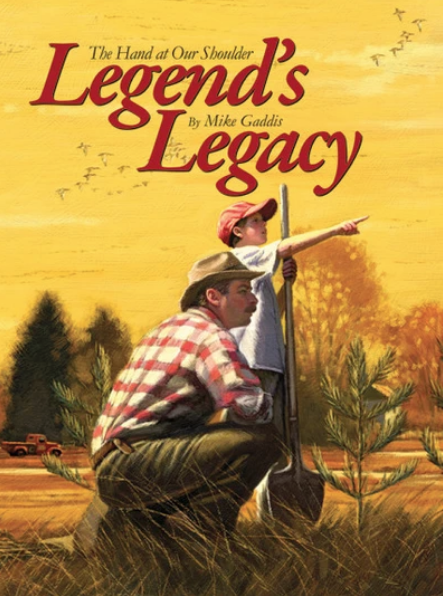

There were moments of infinite beauty and sharing, when someone laid a hand at our shoulder and led us there. So that later we might lead another, in turn. Here, in parables of incomparable warmth and intonation, the author of the celebrated books Jenny Willow and Zip Zap, Mike Gaddis, explores the enchanting realm of outdoor mentorship. Not only in kind and gentle remembrances, but in intuitive vignettes, present and future.

There were moments of infinite beauty and sharing, when someone laid a hand at our shoulder and led us there. So that later we might lead another, in turn. Here, in parables of incomparable warmth and intonation, the author of the celebrated books Jenny Willow and Zip Zap, Mike Gaddis, explores the enchanting realm of outdoor mentorship. Not only in kind and gentle remembrances, but in intuitive vignettes, present and future.

Legend’s Legacy stands unparalleled as an affecting commemoration of the most endearing aspects of our sporting traditions—an inspiring tribute to those who cared, who taught us then and guide us still. Buy Now