By crafting knives, totes and other useful tools, you are taking an extra step as an ethical hunter by making the fullest possible use of your bird.

Among turkey hunting enthusiasts, beards which dangle a foot from a turkey’s breast or have the breadth of the spine of a James Michener book certainly merit attention and draw descriptions such as “he had a paint brush beard” or “that gobbler was a strutting Picasso.” Similar awe is accorded out-sized turkeys which passed the 20-pound mark about the same time they abandoned jake status for adulthood. Yet such examples of super size in turkeys are not the ultimate measure of trophy status. That is reserved for the one attribute of a turkey which can consistently give a dependable index to a turkey’s age—its spurs. If a turkey has lived long enough to boast inch-plus spurs which curve like a miniature scimitar and taper to a point which could pass for the end of a knitting needle or an awl, you have a bona fide trophy.

How to Make Functional Tools From Inedible Portions of Wild Turkey

Such spurs, and for that matter all spurs from mature turkeys, should be saved as the treasures of the hunt they most assuredly represent. Yet preserving spurs or, better still, utilizing them in crafting functional, eye-catching tools, is but one of many ways in which inedible turkey parts can be turned to fine use. Wingbones can become the key element in suction yelpers, legs and feet transition to bookends, a section of leg holding a spur the handle for a fixed-blade knife, the same portion of a bird rendered into a turkey tote, and much more. Let’s look at some tools and treasures crafted from bones.

Whatever the project, and the range of decorative uses actually transcends that of possible tools, with such efforts you have taken an extra step as an ethical hunter by making the fullest possible use of your bird.

Making a Tote from a Turkey Leg

There are various ways to carry a gobbler from the woods to your vehicle, and no matter what method you use it’s likely the triumphant trip will find you figuratively walking on air. However, to my way of thinking a truly special aura is added when the bird is transported with a device made from the leg bone of a long beard taken on another successful outing. To make a turkey tote, begin by cutting off a turkey’s leg at the joint, remove the foot at the opposite end, and without too much more work you have the makings of a turkey tote. Clean out the bone marrow, leave the skin intact, carefully dry it, apply a couple of layers of clear varnish or similar sealer/preservative, and then run a strong leather thong or a piece of parachute cord through the bone. After tying it off, singeing the ends if you use cord, and getting the right length, you have a way to carry one turkey with a piece of a previous gobbler. The leg bone is your handle.

Master hunter and callmaker Parker Whedon “running” a handmade wingbone yelper in an interesting woodland setting

Turkey Leg Bookends

I can imagine no better way to display some of your prized books on turkey hunting than having them stand between bookends crafted from the feet and lower legs of a fine gobbler. Take a turkey’s legs, with the feet and spurs intact, and dry them in the appropriate position. You will want the toes and feet spread as if the bird was walking and with the leg portion erect. When they are fully “cured,” apply bronze paint. Once affixed to suitable bases (you will want to add considerable lead or some similar type of weight to the underside of the base if you plan to use the book ends with many books), you are in business.

Fixed-Blade Knife with Turkey Spur Handle

A couple of decades ago I killed a fine gobbler in Missouri which sported impressive spurs. A fellow in the hunt camp offered to make me a short, sturdy skinning knife using a leg and spur as the handle. The swap off was that he got to use the other leg for a similar purpose for a knife of his own. To me it was an irresistible offering, and in due time my fixed-blade knife arrived. The spur, beyond its aesthetic appeal, serves a functional purpose in providing a good, non-slip grip on the knife as the user lets it extrude between his middle and ring fingers. Anyone reasonably conversant with basic knife construction should be able to replicate the process my friend used.

It involves some understanding of knife-making procedures, with the key first step being preparing the turkey’s leg in the same fashion covered above for a turkey tote. It is also important that the tang of the knife extend virtually the full length of the leg bone. That will give it the strength and “backbone” needed for demanding work as such as skinning a deer. Obviously you don’t need as much strength for tasks such as caping a turkey.

Making a Wingbone Turkey Call

The oldest form of “manufactured” turkey call is the wingbone yelper. The use of wingbones to call turkeys dates back to Native American hunters who used such devices long before the arrival of Europeans. In skilled hands, a wingbone call can produce most of the key sounds in the turkey’s vocabulary—clucks, yelps, kee-kees, and even gobbles. Moreover, as my mentor in the sport and a maestro on the wingbone, the late Parker Whedon, liked to put it: “I am partial to a wingbone yelper because it carries the spirit of the turkey in it.”

While crafting one’s own wingbone call takes some patience, constructing one which is perfectly functional and capable of serving a hunter for a lifetime is comparatively simple. Wingbone calls come in several forms. Some involve two sections of bone; others three, and there are various arrangements of the humerus, radius, and ulna bones. Different configurations use all gobbler bones, all hen bones, mixed hen and gobbler wingbones, and bones in combination with river cane or other materials. However, most experienced makers generally agree that those calls made from the radius of a hen (the small bone in the middle joint of the wing) and the ulna of a gobbler work best to replicate hen sounds. Also, two-piece yelpers are easier to make and use than three-piece ones.

Hunter crafts a wingbone yelper

Begin by removing as much of the flesh and sinew from the bones as you can. A dull paring knife is a good tool for doing this. Then boil the bones in water for a quarter of an hour or so, afterwards once again using a paring knife to remove any remaining flesh and cartilage. Next use a jigsaw or rat-tail file to cut away the joints. Be sure the leave the “bell” or flared area on the ulna in order to enhance volume and improve the way sound carries. With a pipe cleaner and a small, stiff brush, remove the marrow from inside the bones along with any pith. You can, if desired, use a bleach solution at this point to whiten the bones, although some prefer the soft, ivory-like patina of untreated ones.

When the bones have been cleaned and dried, you are ready to assemble the yelper. One end of the radius will be discernibly flatter than the other. This will be the mouth end. Insert the other end of the radius into the smaller end of the gobbler bone for a distance of a quarter inch then position the two bones so that the call makes a gentle curve. Once properly aligned, bond the bones with heavy-duty glue, making sure none gets inside to block the airway. Wrap the joint with tape or thread for additional strength and a better air seal. Push a pipe cleaner through the yelper before the glue sets to make sure you have a clear air passage.

A pair of two-piece wingbone yelpers made by turkey hunting greats Parker Whedon (bottom) and Lovett Williams (top)

Once the glue has dried, all that is needed to complete the call is a mouth step and, if desired, a lanyard. A slice from a rubber bottle stopper with a hole cut in the middle so it fits tightly over the mouthpiece can serve as a mouth stop. Slide it along the bone until the mouthpiece fits properly in your lips. You can bind a snake guide of the type used with fly rods at the wrapping point where the two bones attach to hold a lanyard. With that you are ready to start calling, although proficiency takes plenty of practice.

One final thought—all these projects except the one involving bookends involve the creation of an item from one turkey used in connection with luring another one to the gun, carrying it from the field, caping it or dressing the bird out. Somehow this linkage between generations of turkeys, a sort of hunter spiritualism if you will, is at once appropriate and appealing.

About the Author

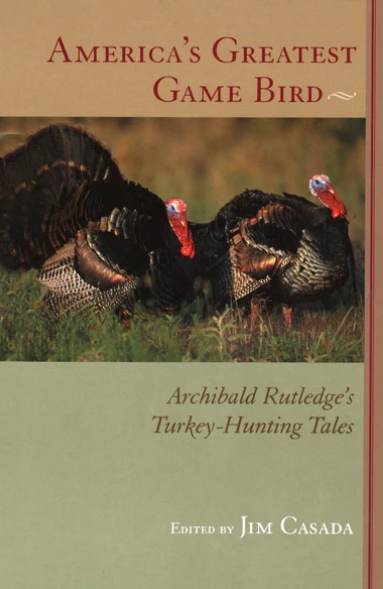

Jim Casada is the Editor-at-Large and Book Columnist for Sporting Classics magazine. An avid turkey hunter, he has written extensively on the sport, and three of his books in the field, Remembering the Greats: Profiles of Turkey Hunting’s Old Masters, The Literature of Turkey Hunting, and America’s Greatest Game Bird (a collection of Archibald Rutledge turkey-hunting tales he edited and compiled) are available through the Sporting Classics Store.

During the first half of the twentieth century, Archibald Rutledge hunted wild turkeys in the woodlands surrounding his ancestral South Carolina plantation. He became wise in the ways of the wary creature and wrote prolifically about the sport.

During the first half of the twentieth century, Archibald Rutledge hunted wild turkeys in the woodlands surrounding his ancestral South Carolina plantation. He became wise in the ways of the wary creature and wrote prolifically about the sport.

In this collection, noted outdoor writer Jim Casada gathers thirty-four of Rutledge’s finest turkey-hunting yarns. Shop Now