There is probably no subject connected with shooting about which so much nonsense has been written and spoken as the distance at which game can be killed with the rifle. This was bad enough in the days of muzzleloaders. It has become doubly bad in these days of long-range and mid-range breechloaders. We now know that such shooting as Cooper and a host of novelists have ascribed to their heroes, such shooting as we have all in our early days read about as being common among the backwoods hunters, was impossible with any rifle, and especially with the small-bored rifle and roundball then almost universally in use among hunters in the woods. But now that rifles are found in every shop that will shoot into a two-foot ring at 500 yards (under target-shooting conditions and care), it is quite natural to suppose that game can be killed as a matter of course at three or four times the distance at which it could once be done.

More game is now killed at 200 yards and over than was formerly killed at that point. But this is not because of any improvement or discovery in distant shooting, but because game is scarcer and wilder, and more chances must be taken, and because the ease of loading the breechloader and procuring its ammunition makes people more liberal in expending ammunition. I do not hesitate to assert that no advance whatever has been made in the art of killing game at long ranges, except in so far as the breechloader allows one to fire more shots before the game gets too far away. I say this notwithstanding the fact that the popular opinion is quite the other way.

High Peak by Brett James Smith.

The old muzzleloader by the use of a lengthened ball and more powder could, with globe-sights, be given a great accuracy at quite long ranges. This was perfectly understood by most of the old-time hunters, who often went to the annual “turkey-shoot” equipped with a weapon that at 200 and 300 yards can hardly be beaten today by any of the boasted breechloaders. Many of those who hunted on open ground used the “slug,” or long ball, and some used it even in the woods. Many long shots were made with it, and probably more game was killed at long range out of the same number of shots than is now killed with the best of modern rifles at the same distance. They all did plenty of boasting of their long shooting. But from long-range shooting proper, such as we are now considering, they nearly always abstained. This was not because they could not do it, but because they soon learned that, whatever their skill at the target or turkey, at measured distances, it was far easier to get closer to game than to hit it at long unmeasured distances.

There are several reasons for the extravagant ideas afloat about the distance at which game may now be killed.

First: The incurable mania for gilding the gold of simple truth. This afflicts hunters as badly as it does fishermen.

Second: The love of “scissorers” on a newspaper for copying everything that savors of a good fat “whopper” such as the stuff that has gone the rounds of the United States this year about the Boers of South Africa knocking over springboks at 800 and 900 yards as a matter of course.

Third: Sincere and natural mistake in overestimating distance, a thing that scarcely any of us can learn to avoid, and that causes the oldest hunter many a miss. The beginner sees a deer at a long distance, looking more like a small fawn than a full-grown deer. He shoots, and perhaps the deer falls at the first shot.

“Ge — ra — shus! What a shot! Four hundred yards!” exclaims the delighted novice. He hastens to his game without stopping to measure the ground. He pants and puffs in getting over to it as I have seen older hunters do in lifting a 120-pound buck on a horse, trying to make themselves believe it weighs 250 pounds. When he reaches home, the ground, still plainly seen by Fancy’s eye, has expanded to 450 yards. When he comes to tell of his wonderful shot, he very naturally wants to do himself full justice, and so he leaves himself a little margin of 50 yards more for possible error. And to the day of his death he will sincerely believe that he killed that deer at almost 500 yards. And to the day of his death this idea will be a mental whirlpool that will suck in and whirl out of sight all the driftwood of contradictory facts that years of later experience can throw in his way.

Now the novice was perfectly right in one point—that he made a very long and very fine shot. The deer was only 200 yards away, but he was still right in calling it a long shot; for notwithstanding the popular impression to the contrary, 200 yards is a long distance to hit a deer even in the most favorable position.

The very swiftest ball or the most speed-sustaining ball you can fire from a rifle falls fast enough in 250 yards to miss every deer or antelope at which it is fired with the sights set for a distance 25 yards on either side the animal; either undershooting or overshooting it. You will find that at 300 yards a mistake of 20 yards in your estimate of distance will cause a miss, at 400 yards a mistake of 15 yards, etc. These figures are of course not exact and will vary with the rifle. But they are not over three or four yards out of the way for the best long-range rifles.

If you doubt figures or anything that savors of “theory,” put up a target at 200 yards with your rifle sighted to that point. Fire a few shots, receding from the target 25 yards each time and firing with the same sight. But do not try to hit the bull’s-eye, but only to discover the fall of the bullet.

Having satisfied yourself what the rifle will do, find out what you can do in estimating distance. Try it first in timber, making an estimate of the longest distances and then pacing them. Then try it on quite open and level ground, estimating and pacing up to 400 yards only. There will be a startling shrinkage of conceit somewhere.

But perhaps you think the faculty of judging distance can be cultivated. Of course it can be improved. By doing nothing else it might even be cultivated to a high enough state of perfection to make five bull’s-eyes out of six up to 400 yards with the target shifted at every shot. But with such time as one can generally devote to that business, he will be more apt to miss the bull’s-eye five times out of six.

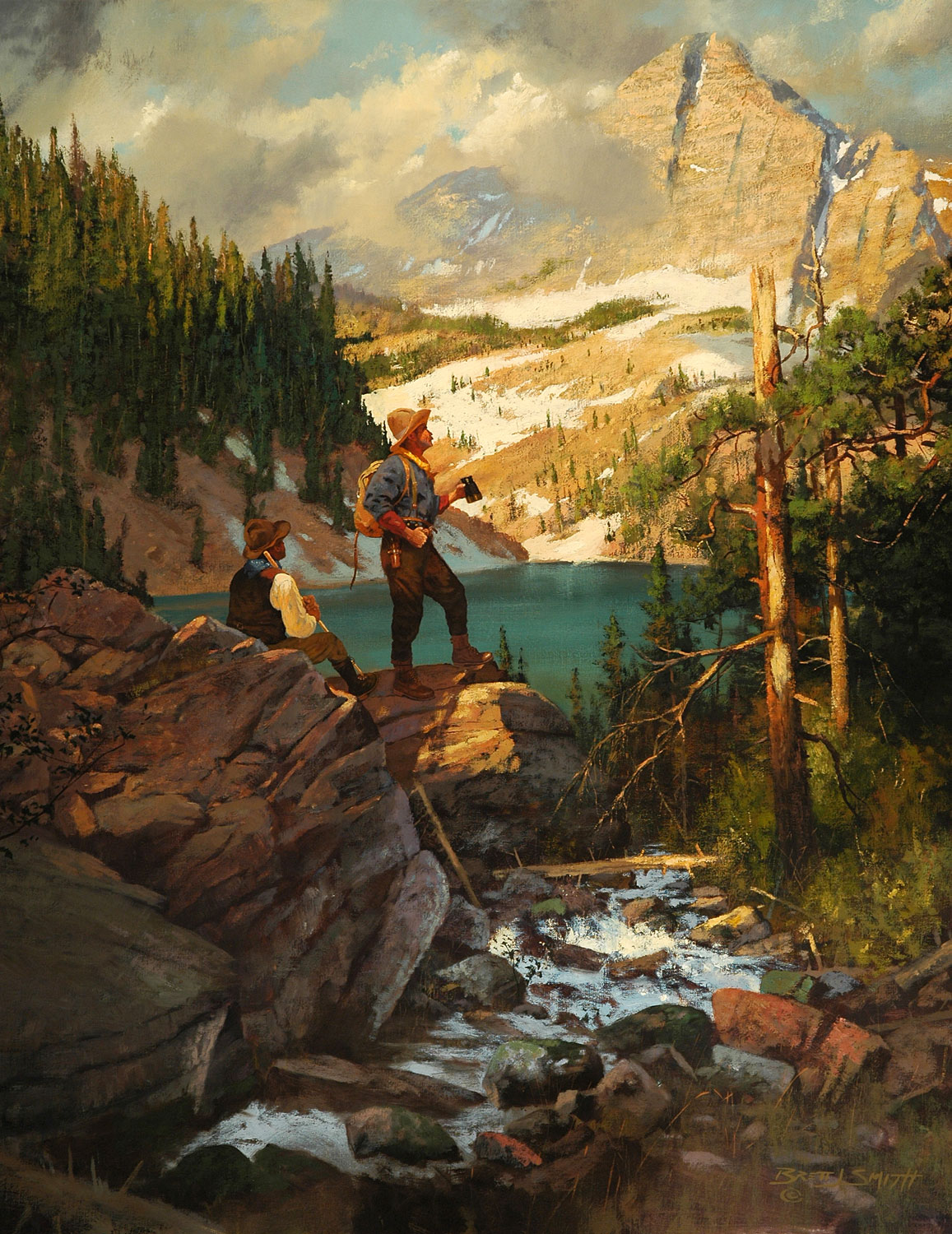

High Country Hunter by Brett James Smith.

But suppose you are quite an accurate judge of distance under the above conditions. Recollect there is no antelope there just ready to leave; no rifle in your hand, with your finger itching for the trigger. The difference that this alone makes is almost inconceivable. There is also another tremendous difficulty, the ever-shifting conditions of ground, light, etc., which occur in hunting. Now uphill, now downhill, here through timber, there over timber, through brush or over brush, up canyons and across canyons, over ridges and over flats, often with scarce a second to spare, judging distance in hunting is a vastly different matter from what it is on always the same kind of ground with plenty of time and no game in sight.

Moreover, whatever your skill may be, your gauge unconsciously shifts with the ground. The standard you use on the plains today will not do for the foothills tomorrow; the one you use in the foothills is too small when you get upon the mountain’s breast; this fails you again when you get among the higher peaks; and when you return to the lowlands you are again “all at sea” for a few days.

Speaking of the inside of St. Peter’s at Rome, Byron says:

“Its grandeur overwhelms thee not;

And why? It is not lessened, but thy mind,

Expanded by the genius of the spot,

Has grown colossal.”

Who has not felt this when among the mountains, and wondered at the ever-changing deceptiveness of heights and distances?

Traveling once with a friend who was boasting of his ability to roll deer right and left at 500 yards running or standing, and whom this poetry failed to touch (as it will the reader, being the only poetry in the book), I asked an old surveyor at whose camp we stopped how he could estimate distance.

“Well,” said he, “when I stay several days on one kind of ground I can make a tolerably fair guess on short distances. But as soon as I get on a different kind of ground, I don’t know anything.”

Considerable practical skill may, however, be cultivated up to 250 or even 300 yards on the plains, and there are hunters who can judge distance well enough to hit an antelope at 200 yards three times out of five at the first shot, all other conditions being of course complied with. It is doubtful, however, if anyone can do this anywhere but on such open ground as antelope frequent.

If you think I underestimate what is good shooting at 200 yards, look over the 200-yard scores made at matches by our best target-shots. Recollect, too, that these scores are generally better than can be made by any mere hunter, the difference being that the hunter can generally shoot as well at game as he can at a target, which the mere target-shot cannot do. Remember, too, that the bull’s-eye is clear white or black on a black or white ground, is eight inches in diameter, is always in the same light, position, etc., and that its distance is known to a foot and the sights set exactly to it. The target-shot has every advantage, the hunter every disadvantage. These scores are nearly all made, too, with globe sights. Take the best of these scores, and bear in mind that it takes a “five” shot to hit an antelope with certainty, and even that when near the edge may represent only a crippling shot; that a “four” shot will hit only about half the time, and then probably cripple him; and that all the rest will be quite sure to miss the animal entirely or only break a leg.

“Shall I shoot from where I am or try to get closer?” is therefore a very important question. Except upon quite level plains the chances of getting within 200 yards are always greater than the chances of hitting beyond that. The chances of getting within 150 yards are generally greater than the chances of hitting beyond that. The chances of getting within 100 yards are often greater than the chances of hitting beyond it. I have had a pretty high degree of skill in guessing distances, adjusting sights and hitting natural marks up to 400 yards or more. But I am perfectly satisfied that if I had never seen a long-range or mid-range rifle, if I had hunted always with a rifle that would not shoot an inch beyond 125 yards, I should have killed much more game than I have. For that very skill has beguiled me too often into opening a cannonade when I could easily have gotten closer. And this even with wild antelope on quite open ground.

For the past three years my rule has been to shoot at nothing beyond 150 yards if there is an even chance of getting closer to it, and not to shoot even that far if there is a fair prospect of shortening the distance. I fully believe I have gotten more deer by it. I certainly know that there have been fewer broken-legged cripples. For deer and antelope on the plains, 50 yards might be added to this distance, for elk another 50 yards and for buffalo another 50. Beyond that point you had better make it a rule to get closer.

All this is, of course, on the assumption that the game does not see you. If it sees you, longer shots must often be taken. But I have seen deer so tame that your chances of running or even walking 60 or 75 yards closer were much greater than the chance of hitting at 200 yards. And this, too, when they were looking directly at one. But where the game is not alarmed it is a safer rule to treat the best long-range gun as if it were a short-range muzzleloader, and turn every point to make a sure shot.

I know that some will disagree with this. I know all the stories about how so-and-so killed an antelope at 800 yards, and how what’s-his-name hit a goose at half a mile, and how the other man hit a deer in the heart running at 500 yards, etc., etc., etc., ad infinitum. I know, too, how it all is done. Nearly everyone who has played much with a long- range rifle has made remarkable shots at long distances. I have made my full share of them. So long as these are classed where they belong, as accidental shots, it is well enough to tell of them. But when anyone attempts to draw conclusions from them, then, in the name of philosophy, I protest. Until one can make them at least once in 10 trials at unmeasured distances, they are utterly worthless to reason from, even though considerable skill entered into them.

One way in which game is often killed at long distances is by it standing for “sighting shots” until you finally get its range. But it is quite as apt to jump at every shot or two just enough to derange your calculations. And in either case, the shooter is very apt to forget all about the number of shots that did not hit. Still, where it is evident that game cannot be more closely approached, this is sometimes an effective way of getting it; though the chances of hitting it at all are always largely against you.

The delusion of long-range shooting is fostered by the ease with which with a long-range rifle the dirt can be made to fly just over or under a distant object. We shall see in another place the worthlessness for hunting of what is generally known as the “line-shot,” by which is meant a shot on a line running up and down through the mark, and that the only “line-shot” worth anything for hunting is on the horizontal line, the hardest of all to make. But it takes bull’s-eyes instead of line-shots to kill game. Moreover, what appears to be only a few inches deviation from the distant mark is really a few feet. And to reduce those feet to inches without measuring the distance will be found a little problem the solution of which will generally puzzle you until the game gets weary of awaiting the answer.

The main difficulty of accurate long-range shooting cannot be obviated by telescopic or any other kind of sights or arrangement of sights. The estimate of distance remains the same whatever

sight be used.

Whenever it is necessary to shoot beyond the point blank of your rifle, discount your estimate of distance about 20 percent on 200 yards, 25 on 300, 30 on 400 yards, etc. And whenever in doubt between two estimates of distance, decide at once in favor of the shorter one. By letting long shots go where there is a prospect of getting closer you will, of course, lose some game. But you will get more in the end.

This article is Chapter 28 from The Still-Hunter originally published in 1904.