Snakes put the wild in wilderness, make you pay close attention and keep the outdoors from being controlled adventure, a jillion-acre theme park.

I bought one of those Carolina Kettles, you might have seen them advertised here, the reproduction of the old syrup cookers—cast iron, fifty, sixty gallons, heavy enough so you won’t have to worry about anybody ever stealing it. I have a fireplace, too, and between the two, they eat up a lot of wood.

I don’t boil maple sap, but I used to. I don’t boil cane squeezings, either, though I almost wish I did. The Carolina Kettle sits out in the yard. The fire is in it, not under it, and when friends gather around, I’ll fire it up and we’ll down a dram or three. Now, I’ve cut my share of wood in my younger days— ten, twenty cords every year, back when I bucked a 056 Stihl up in Minnesota in the fanny-clinching cold and where there were no snakes to bother you. But now I live way down south on an island nobody has ever heard of, no bridge, no yoga, no yogurt and all the fast food has fins and fur and feathers. I’ve downsized to a saw half as big, but I still cut wood for the fireplace and for that Carolina Kettle.

All kind of things will bite you here, including spiders and skeeters and gators and sharks and ticks, and if you hunker in the pine straw and try to chuckle up a turkey, the chiggers will gnaw your nubbins till you’ll wish you’d bought a tender timer bird instead.

A friend of mine by the name of Miss Ruthie was working her crookneck squash when a copperhead reared up out of the weeds. She beat it with a trowel and she beat it with a hoe and the head was still latched onto her thumb when she finally got to the EMTs. She was tore-up drunk when I ran into her a couple of weeks later.

We were down at Mudbank Mammy’s, the concrete floor beer joint where the gumbo makes you sweat and they sweep up the eyeballs come closing time. Miss Ruthie was hooked over the end of the bar, daubing like a sick chicken. “They made my thumb look like a dick!” she hollered and held the offended digit for all to see. And she was right; they did.

Miss Ruthie did not survive that snake. OK, she was asthmatic and arthritic, but we all reckoned the snake is what finally did her in. They buried her next to her kin in the Mary Dunn Cemetery, where the pines whisper their sad secrets of sea breeze and the Spanish moss hangs from the ancient oaks like long gray strings of tears.

Miss Ruthie loved her birds and her family hung a feeder over her grave, and if you go down there to pay your respects, you can see the jays and chickadees, sometimes cardinals and buntings, flitting about like little multicolored angels.

That’s what I was thinking about when I stacked the firewood under the house, fuel for the fireplace and the kettle. We don’t have basements down here, but the houses are all up on pilings to keep them above the storm tides. It a good place to stow your decoys and layout boat, to hang your cast-net, fishing rods and all that other stuff women won’t tolerate on the front porch. It’s a good place for firewood, too, if you’re not worried about snakes. I was plenty worried, but I stacked it there anyway. A man just can’t have a pile of split oak sitting out in the rain.

We got our first cold snap the last week in October. I broke out my old Mauser, ran through a few rounds to knock the dust out of the bore. It printed like it always does, the first shot high and left, the next three holes so tight you could cover them all with a half dollar. I threw a rifle, coat and handful of shells into the Jeep, set the alarm for 4:00 A.M.

I could have just as well laid up in bed. Cold snap, or not, the skeeters were still out in force. I tucked my face-net into my jacket collar and they roosted like buzzards along the rim of my hat, a dozen or two at a time, and made sorties against nose and ears whenever either came close to the netting. And then, about sunrise, there commenced a drizzling rain. I was halfway down the ladder when my boot slipped.

Sometimes not falling is worse than hitting the ground, especially this leaf-mold ground in these cool green woods, when it’s all soppy and spongy from the rain. I caught myself with three fingers of my left hand, swung like a pendulum eight feet up, and by the time I pulled into the driveway, my neck, back and shoulders felt like I’d been run over by a team of mules.

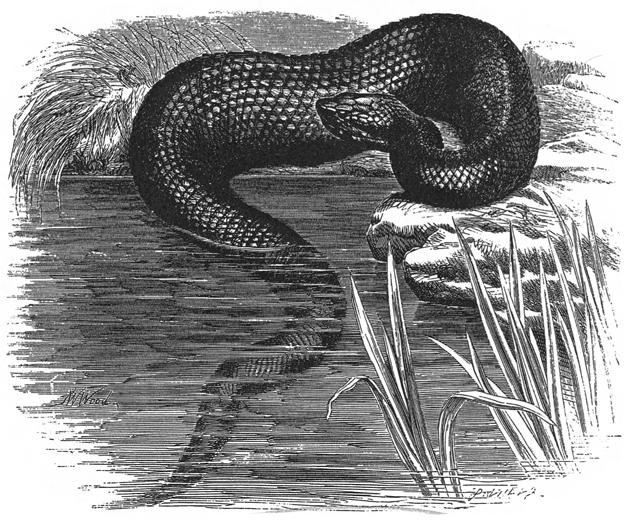

That’s when I saw the copperhead, coiled and dead. It didn’t take long to figure out what happened. It came out of the woodpile, cuddled up to the warmest thing it could find, the back tire of the Jeep. I had walked within six inches of it in the dark and killed it when I backed out of the drive. And all of a sudden, my back did not hurt anymore.

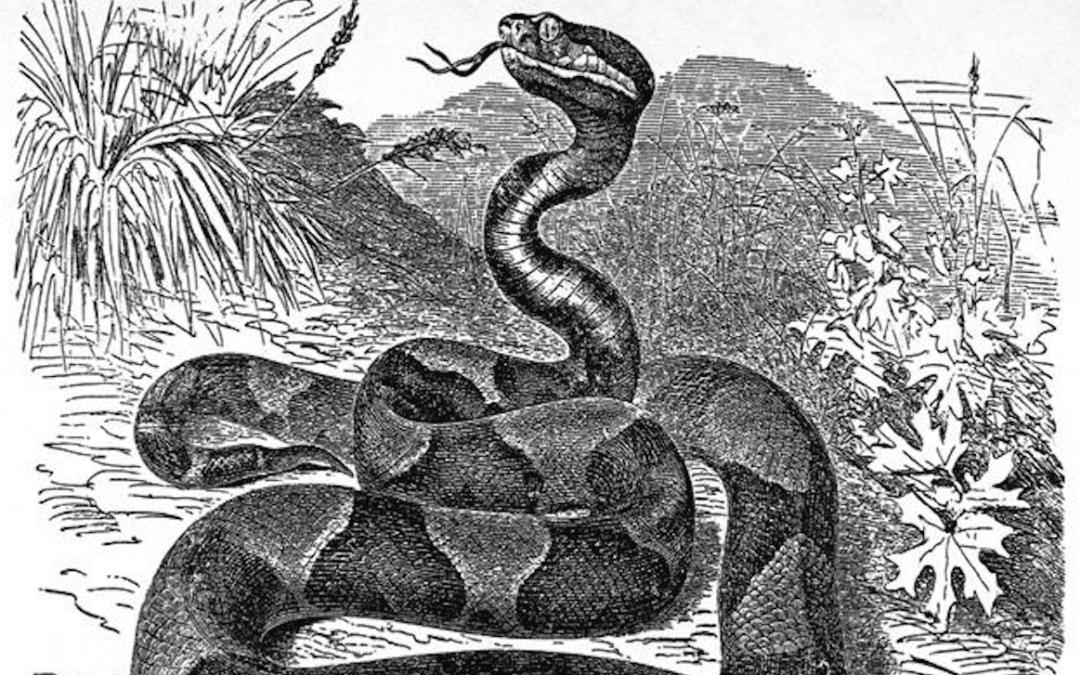

A couple of weeks later, another snake cured my toothache. I had split a molar on a six shot and put off fixing it till it took to throbbing like it was ready to fly right out of my jaw. I was choring around the place, feeding the dog and such, before getting on the boat and trying to scare up a dentist on the Wrong Side, which is what locals here call the other side of the river, the entire North American continent. The dog food was in a coon-proof box, over in the corner by the leaky hip boots and that three-horse egg-beater Johnson I’d been meaning to get running whenever I got around to it. I was reaching for the scoop when this bigass cottonmouth rose up like a cobra ready to strike.

Dammit, what a snake! Dull-eyed and greasy, big around as your wrist, big enough to kill you. But I wasn’t ready for a fight. The nearest shotgun was two floors up in the back of my closet and the shells were someplace else. You saw an old man scramble so.

I came back down with a .410, but the snake was gone. “This won’t do at all,” I said to myself. “He’s crawled off somewhere and I’ll find him again when I least expect it.”

So I fetched up a garden rake, began hooking buckets, totes, boxes and dragging them away from the wall. About halfway to a heart-attack, the cottonmouth rose up again from behind a crate of bluebill decoys. And I was ready with the .410. Forty-seven and one-half inches, minus his head. I laid him out in the driveway and pulled tape, just to be sure. That’s when I realized I hadn’t thought about that tooth since the whole ordeal began. Yeah, I ended up pulling it out, but not for a couple more weeks. Snake therapy lasted that long.

The Good Book is mum on spiders and ticks and chiggers, but it says the Lord put a snake in the garden with Adam and Eve. The snake tempted Eve and Eve tempted Adam, which she would have likely done even without the snake getting into the middle of things.

But God got disgusted and cursed them all. From henceforth and forevermore, Adam would earn his bread by the sweat of his brow, Eve would bear her children in pain, the snake would strike her childrens’ heels and the children would crush his head—if they got the chance.

Gospel Truth or folklore, that’s pretty much the way things worked out, but umpteen generations later, this whole snake business comes down to us as a sort of left-handed blessing. Okay, maybe you don’t have venomous snakes in your neighborhood, but African killer bees have spread farther than you might expect. And I’ve seen yellow-jacket nests in Minnesota as big as a barrel, the ground stained by wings for three feet in all directions. Blunder into one of these and you’ll be dead before you hit the ground. Don’t even get me started on lightning, flash floods and wildfire.

Snakes, bugs, whatever, this is what keeps the wild in wilderness, even if it ain’t a grizzly or a puma. This is what makes you pay close attention, what keeps the outdoors from being controlled adventure, a jillion acre theme park.

Maybe my piles of decoys and fishing rods and leaky hip boots ain’t wilderness, even if my woman might call it a swamp. But wilderness is just a hundred yards away. I’ll keep my eyes peeled, watch my step and keep that .410 handy. And I’ll still stack my firewood under the house.

This is a full-color edition of the very first Boy Scouts Handbook, complete with the wonderful vintage advertisements that accompanied the original 1911 edition, Over 40 million copies in print!

This is a full-color edition of the very first Boy Scouts Handbook, complete with the wonderful vintage advertisements that accompanied the original 1911 edition, Over 40 million copies in print!

The original Boy Scouts Handbook standardized American scouting and emphasized the virtues and qualifications for scouting, delineating what the American Boy Scouts declared was needed to be a “well-developed, well-informed boy.” The book includes information on:

- The organization of scouting

- Signs and signaling

- Camping

- Scouting games

- Description of scouting honors.

Scouts past and present will be fascinated to see how scouting has changed, as well as what has stayed the same over the years. Buy Now