Rediscover what six or seven generations of American outdoorsmen enjoyed for 150 years. The all-American lever-action rifle. Long may it reign.

We Americans are delightfully inventive. We came up with baseball, basketball, the Boy Scouts, Broadway musicals, jazz, rock-and-roll and lever-action rifles. I’m not sure which I enjoy more, but I’m convinced I’m not alone in my growing re-appreciation of lever-action rifles. Cock your ear to the breeze and you’ll hear the metallic schlick schlick of America’s rekindling love affair with lever-action rifles.

Everyone from Henry, which started it all way back in 1860, to Big Horn Armory, which is setting new benchmarks in power, is building new and better lever-actions to meet the growing demand for these all-American classics.

The 1860 Henry kindled our love affair with levers, giving us not only our first viable repeating rifle, but a fully contained rimfire cartridge, the 44 Henry Flat, to fire through it. The flames grew hotter six years later when Winchester unleashed the famous Yellow Boy. With the stronger, steel-action Model 1873 and its reloadable, centerfire 44-40 cartridge, the lever-action flames were at a full roar. From that date through the mid-20th century, the lever-action was arguably the most popular repeating rifle in North America. It might not have actually won the West, but sure helped define it. Can you even imagine John Wayne pulling a scope sighted Mauser 98 from a saddle scabbard or Lucas McCane bolting 13 rounds down main street as the opener for The Rifleman?

The lever-action’s sparkle didn’t tarnish until Teddy’s Rough Riders met the Spanish Mauser in Cuba. Even after that hard lesson levers continued as the rifle of choice in deer woods and mountain meadows. It wasn’t until the Treaty of Versailles that some four million returning doughboys fully embraced the Springfield bolt-action and its powerful 30-06 cartridge. How could they ignore the extra reach, punch and precision of those high-velocity, spire-point bullets when compared to the flat-nosed slugs in Granddad’s old lever action?

By the time WWII and the autoloading Garand came along, millions of American hunters had already set their lever-actions in the back of the closet. The M16 nudged it even farther back.

Despite all this, the old cowboy guns hung on, remaining surprisingly popular through the 1960s, propped up by a surfeit of Hollywood westerns. But, inexorably, lever-actions lost fans. By the end of the 20th century they had become bit players, touchstones to a romantic past. Buffalo Bill. Annie Oakley. The American cowboy. Lever-actions, working tools as ubiquitous as axes, became specialty items for close, woodland still-hunting, for stand-hunting over short-range fields and meadows, for tributes to old traditions.

Many, if not most of us, assume lever-action popularity declined due to the lever’s weak lock up or the inherent inaccuracy of the design. But John Moses Browning had slammed the vault on the weak locking issue with the Model 1886 and 1894. The Winchester M95 and Savage M99 not only handled fully modern, high-pressure cartridges such as 30-06 and 308 Winchester, but sharply pointed bullets, too. As late as 1955 Winchester was still introducing new lever-action designs, its Model 88 chambered for high-pressure, high-velocity 243 Winchester, 284 Winchester, 308 Winchester and 358 Winchester loads. Even a European gun maker, Sako, tried stealing a slice of the lever-action with its 1962 Finnwolf. Browning’s BLR didn’t come along until 1971. To this day it’s chambered for high-pressure 22-250 Rem., 270 Win. and even 7mm Rem. Mag. No, we can forget about lever-actions being too weak for the game.

As for accuracy, gunsmiths and serious riflemen long ago learned to relieve screw pressure here and there and tune triggers until a good lever-action — even the tubular magazine styles — could shoot MOA, sometimes even better. Marlin solved the scope mount issue with its side ejection. Winchester followed suite with angle-eject late in the game, but did it nonetheless.

Why, then, have lever-actions flagged to the back of the field? My observation is it had more to do with cartridges, bullets, image and assumptions than the action itself. The unbreakable image of a cowboy on a horse just couldn’t keep pace with a Weatherby on a rocket. Once magnum-hungry hunters tumbled to the benefits of ballistic efficiency, round- and flat-nosed bullets became anachronisms. Appropriate for buckhorn sights. Woefully unable to take advantage of a telescopic sight.

Then came the advent of inexpensive travel and the restoration of big western game such as elk. Even if a whitetail hunter back east found the old 30-30 or 32 Winchester more than adequate for the woods he was hunting, there was this chance for one day breaking free, for living that Rocky Mountain high. Might as well arm up for the big stuff and long ranges, just in case.

But let’s not overlook the influence of varmint shooting. With big game numbers at ebb tide in the early 20th century, country folks took to sniping woodchucks in the east, prairie dogs in the west. Wildcatters turned everything and anything with a primer pocket into a 22– or 25-caliber wildcat, each seemingly faster than the last. By the late 1930s pretty much everyone understood the possibilities 3,700 fps brought to the game. All they had to do was scale it up. After WWII they did.

Shooting fashion changed. No longer did we stand and deliver. We sat or lay prone. If we could hit ground squirrels at 400 and 500 yards, why not pronghorns, mule deer, elk?

Most of us know the rest of the story. Military snipers, Gulf wars, laser rangefinders, turret dialing, ballistic calculators, wind meters, smartphone apps, bluetooth connections…. Lay down, stay down, call in your longitude and latitude and launch one.

And that has apparently launched a lever-action revival.

Yes, the lever is cool again. Just as jaded magnum shooters in the 1960s rediscovered the bow and arrow, 2020 hunters are rediscovering the freedom and rush of hunting with a lever-action. No batteries, no calculus, no lasers, no meters, no sweat. Just seven pounds of nicely balanced walnut and steel between your hands while stalking the wilds.

Luckily our lever actions are still around for this. Although Savage and Sako gave up the fight, Winchester, Marlin and Browning hung in there, guarding the embers. Pedersoli reached back to breathe warmth into many of the Old West classics. Marlin added fuel with its pragmatic, big bore Guide Guns. Turnbull warmed nostalgic hearts with its high-end restorations. Big Horn Armory turned up the heat by throwing some massive logs into the fire, and Henry fanned the flames with some aggressive, well-played marketing.

So it is a new generation or two that has the chance to rediscover what six or seven generations of American outdoorsmen enjoyed for 150 years. The all-American lever-action rifle. Long may it reign.

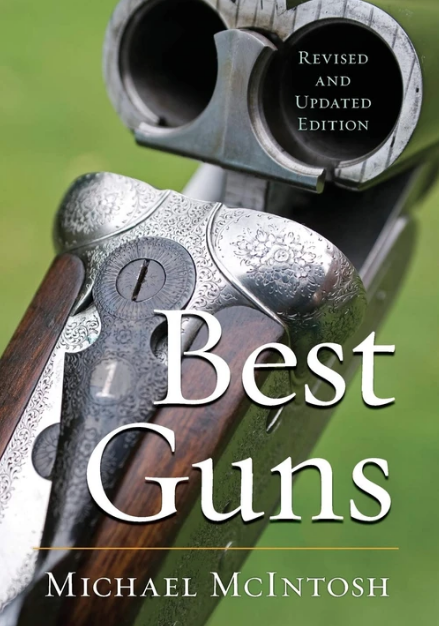

Michael McIntosh offers practical advice on buying, shooting and collecting older guns–what to look for and what to look out for, all based on long experience. McIntosh also offers advice on buying and shooting older guns–what to look for and what to look out for, all based on long experience.

Michael McIntosh offers practical advice on buying, shooting and collecting older guns–what to look for and what to look out for, all based on long experience. McIntosh also offers advice on buying and shooting older guns–what to look for and what to look out for, all based on long experience.

As interest in fine double guns reaches a new high in this country, Best Guns serves as both a guide for the uninitiated and a standard reference for the experienced collector and shooter, all written with the precision and seamless grace that were McIntosh’s trademark style. Buy Now