Peter Ryan on lessons handed down to a son.

Our son, Jamie, is 10 years old. Today, after much pleading, he is with me at a cabin on the South Island of New Zealand, a long way from anywhere. There at the head of the valley the snow looms high overhead, waterfalls cascade off the mountainside and fingers of dark beech forest reach down to the valley floor. The perfect place for lessons to be handed down to a son.

Our days settle into an easy rhythm, splitting wood, scouting for wild red stags then back for dinner. The old fireplace invites a blaze and we oblige – a good fire brings out the boy in every man. Then it’s time to blow the last candle out. Half an hour later, the fire is flickering but sleep is elusive. It’s easy to watch the flames and get lost in memories.

Our days settle into an easy rhythm, splitting wood, scouting for wild red stags then back for dinner. The old fireplace invites a blaze and we oblige – a good fire brings out the boy in every man. Then it’s time to blow the last candle out. Half an hour later, the fire is flickering but sleep is elusive. It’s easy to watch the flames and get lost in memories.

The doctor was doing his best to talk about the weather — anything he could think of except the reason for our walk. There was no getting around the fact that if things were fine, we wouldn’t be taking Jamie, just 20 minutes old, to intensive care. He wasn’t looking good.

In the elevator I wondered about my wife in the operating room and about our boy, so new to the world. It occurred to me that he may only have an hour and that it might be best to steel myself for that. And then it occurred to me that those thoughts have never been any damn good to anyone.

No, if all our little man will have is an hour, then I will love him and take his hand for that hour, let the chips fall as they may. If I’ve ever done a brave thing, that was it.

No, if all our little man will have is an hour, then I will love him and take his hand for that hour, let the chips fall as they may. If I’ve ever done a brave thing, that was it.

But he grew up strong and sure.

It’s the eyes you see first. Not that muddy cape, not the nostrils flared for battle. It’s not even antlers. It’s the eyes, wide and fixed on you and nothing but you.

It happened quickly. Moving through tight cover a rutting young stag charged into view just a few yards away, his face framed by wet leaves. His fierce gaze was right on us, there was no chance or reason to raise the ’06. Slowly reaching back I take Jamie’s hand in mine and give it a squeeze. Don’t move. Remember this. Then the stag spins abruptly and is lost to the mist, his rank scent hanging in the air.

On that happy note our day is done and we trudge down the valley to the cabin, muddy but lit up. Along the way it occurs to me that in his boy’s mind things will be like this forever. I know better, but in the meantime we go on little adventures.

I’ll never be able to give him a million dollars — but I can give him this. These lessons to be handed down to a son.

The lives we live today come with a lot of baggage. Just renewing insurance and recovering lost passwords can soak up the hours. None of that is hard work, but when you pause and watch the ducks circle and gang up and call to each other it’s hard to bear. They feel the change of season, the restlessness in the air, in themselves. Yes, there is work to be done, a hundred small cares and duties. Yet I see them winging across the broken autumn sky, the wanderers of wild places, and wish that I could follow.

Today we’re off to a field to set up against a fence line. That means a blind big enough to hold a man, a boy and Tom the Labrador. I have Dad’s warhorse with me, an 870 Wingmaster, SC grade, put together by the Remington custom shop in 1969. It has pretty black walnut and points better than any magazine repeater should.

We’re all set, but there’s nothing moving. That’s OK, it’s a chance to talk – about the treehouse we’re building, hockey, girls. I give Tom a rub behind one ear, then all three of us settle into an easy silence. What else could I spend my time on that’s better than this? Just sitting with a dog and a boy isn’t doing nothing. We’re busy being friends.

Without warning they are high above us. Jamie and I freeze and Tom stops panting, closes his jaw and goes to full alert. Four mallards cup and sail in, two leave. I clear the Wingmaster and praise the pup up for being staunch, but right now he couldn’t give a damn. He wants those ducks.

That was the pattern of the day, steady ones and twos right through, including a decent haul of Paradise ducks. “Ten more minutes, Dad. Just ten more.” I get more fun out of watching him and the pup than from the birds.

Maybe that’s wrong. Or maybe it isn’t.

We climb slowly, looking for venison, sidling from one spur to the next. We move below the ridgeline as the valley stretches out before us and just like that a fat fallow spike materializes out of the mist. He’s head-on at 200 yards. I check in with Jamie, putting him behind me. The crosshairs veer wildly before the ’06 settles. The shot is a lucky one, the spike flops without a step.

I clear the rifle and turn to Jamie. I can see now that it has cost him — he wanted so much to do something himself. He wanted to impress me, to tell his friends, to take something home. Instead all he could do was stand by and watch. And then he swallows it all down, puts his hand out and shakes mine. Damn boy. I’ve met grown men who can’t do that.

The next few days are spent exploring. Is there anything better than a swathe of new country and no deadlines to meet? We spend hours walking the valley, the crossings too high for his boy gaiters, so I swing him over the fast, clear streams on one arm, a small laugh of joy bubbling out each time. We forage tart blackberries low down, slowly approaching the high ridgelines to glass below.

The next few days are spent exploring. Is there anything better than a swathe of new country and no deadlines to meet? We spend hours walking the valley, the crossings too high for his boy gaiters, so I swing him over the fast, clear streams on one arm, a small laugh of joy bubbling out each time. We forage tart blackberries low down, slowly approaching the high ridgelines to glass below.

After two hours of sketchy four wheeling we hit the boundary. Beyond lies the Molesworth, the biggest ranch in New Zealand at around 300,000 acres. I ask if he would ever want to go there one day. He glances at the vast high plains and endless mountains rolling to the horizon, then looks me in the eye and asks, “Can we go now?”

And it is then that I remember another boy who was just like him. I wonder where he went, and by what crooked alchemy the best of him is somehow standing beside me 40 years later.

The mountains loom, fans of scree spilling down their flanks. Cliff faces show layer after layer of battleship grey, iron-blue and black rock sliced as though the hand of God passed over them yesterday. We sit in the sun below a ridge and ponder the next move. Suddenly there’s a boar trotting quietly through the thicket below. Just in case, I put Jamie right behind me and work the bolt — just one of those instinctual lessons handed down to a son. To everyone’s surprise the boar emerges through a window in the scrub, still at a fast trot. The Swarovski tracks past that thick neck, along the line of the jaw and without any real thought the ’06 rolls back. There is no flinch, no burst of speed. He doesn’t even break stride and is lost in the next dark thorny tangle, but it felt right.

Visibility is just a few feet and some of it is on hands and knees. Dragging him out he just keeps coming. The Barnes hit squarely on the point of the left shoulder, opened through the heart and exited on the opposite side. He was walking dead, carried forward under his own momentum, yet showed no flicker at all.

Coming down the hill, squinting in the bright morning light, Jamie asks if he can have the tusks.

You know it’s cold when the dog doesn’t want to get up.

Ducks are already trading in the distance as we settle. The river is running fast so retrieves will need to be on the ball. Twenty minutes later a single sails in from nowhere, ripping air as it spills back and forth. It folds to a single lucky shot. Tom makes the retrieve nicely and peace settles over us again.

Jamie sees them first — two mallards. One drops to the shot like a stone but the other planes down farther out. I steady Tom and send him, knowing what will happen. He makes a beeline for the still bird but to my surprise charges past. He seems to sense that the far one is more urgent. Maybe he’s more talented as a dog than I am as a trainer.

Hours later, an icy wind has sprung up and the light begins to fade. We pick up the shells and break camp for the last time this year. Without being asked, Jamie threads the ducks onto my carrier and heads off with a load slung on his back – and just like that my little boy is a little man.

Hours later, an icy wind has sprung up and the light begins to fade. We pick up the shells and break camp for the last time this year. Without being asked, Jamie threads the ducks onto my carrier and heads off with a load slung on his back – and just like that my little boy is a little man.

There are more ducks overhead, high against the red-gold cloud, riding the southerly. Tom hears the whisper and watches them with me. In just a few seconds the birds are taken by the wind and gone from sight. Off to parts unknown, they’re a gentle reminder of the sad, sweet thing about moments – that they disappear.

In the heart of the Southern Alps lies a deep valley hung with beech. By our camp a stream rushes clear as air over clean stone. That water has tumbled its way down from the high peaks, soft and cold and sweet. If you stand still for a moment there is no sound but the little river whispering to itself.

We glass and finally make out a chamois, then another and another. There is no point coming at them from below, all those eyes and ears would nail us miles out.

By afternoon we’re up on the spur that forms the right-hand edge of the great bowl of the mountain. Even the spotting scope draws a blank until at last the figure of a female standing against grey rock swims into view. A wise old girl on overwatch, so we circle down. At the bottom of the scree a female is picking around in the open. I spot a hint of white in the low scrub and realize it’s the buck watching from cover.

I put Jamie behind me then go into the dreamlike bubble that a shot like this needs. There is a splash of stones an inch or two over the buck’s shoulder. The buck moves across the face of the scree and then turns downhill, quartering. Drop the crosshairs, shooting quickly now. The buck fades into a small stand of bush.

It’s a hellish place to get down to until we hit deep scree and ride the slide in great bounds, much to Jamie’s delight. I look with wonder at that thick black coat, so soft to the touch, the chastening blankness of those eyes. Jamie is excited, but I put my hand on the animal’s face and we have a little talk. I tell him this buck had a life. He was strong today but getting older, time for another buck to come and hold this place. Night is coming so after a few pictures we begin the trudge out. In the deep scree a burst of grunt gains nothing but a handful of yards. Do five sets, then another five. It seems to me that climbing is about five times harder than it used to be.

Much later over a fire I realize that in a few years Jamie will be able to walk me into the ground. That’s a hard thing to grasp. It seems like yesterday that I was teaching him how to use a spoon.

Much later over a fire I realize that in a few years Jamie will be able to walk me into the ground. That’s a hard thing to grasp. It seems like yesterday that I was teaching him how to use a spoon.

Then I look at the thick hooked horns of the buck and think about all that for a while.

In the distance an avalanche sweeps down one of the valleys, a gentle cloud billowing upward as the rush settles. I’m glad we’re not going that high. The bulls are feeding into the wind, halfway up the flank of the mountain. The only stalk is up through a creek bed, then through forest and finally a long sidle across a mile of rock and thorn. Nothing dangerous but five hours, minimum. In that time the tahr could be anywhere.

Halfway through the traverse we spot nannies. If they bust they could go for a long way and sweep the bulls up with them, but after half an hour of fancy footwork we’re clear.

The bulls are gone, of course. We sit on a spur to plan the next move and it is then that the bulls step out below. There are three but one has length and lots of rings. We close the gap and at the shot he rears up like a mustang but is down in seconds. Seven hours after we started, the bull comes down the mountain. It’s a fine old Kiwi tradition to wear the cape as you go, and a pleasant one at that. Tahr don’t smell like goats — their scent is of stone and dry herbs and wilderness.

Halfway down we pause to rest. I watch the boy, the high snows looming over him. Already he knows how to make camp, to work all day, to find what does not want to be found. Somehow — even in a modern world — these things will give him a compass to steer by, will let him be who he can be.

Halfway down we pause to rest. I watch the boy, the high snows looming over him. Already he knows how to make camp, to work all day, to find what does not want to be found. Somehow — even in a modern world — these things will give him a compass to steer by, will let him be who he can be.

I’ve seen how he looks at my rifle and know that I’m a caretaker of sorts now. A few weeks ago, I found one of my old maps with a cross drawn on a high valley. I’ve never been there and don’t know anybody who has. Next to it, in his child’s lettering, is a date set far in the future. It took a moment to grasp the meaning of that little promise to himself. That date is 21 years to the day since he and I took that long walk in the hospital.

If the fates are kind I’d like to be there too, even if as an old man. I’ll need some help getting up those mountains. Perhaps things will have gone full circle by then, and this time around he can take my hand.

Peter Ryan has hunted and fished across the globe. This is an excerpt from his third book, Hunting – Moments of Truth (Bateman Ltd, New Zealand) to be released July 2021. More at faraway.co

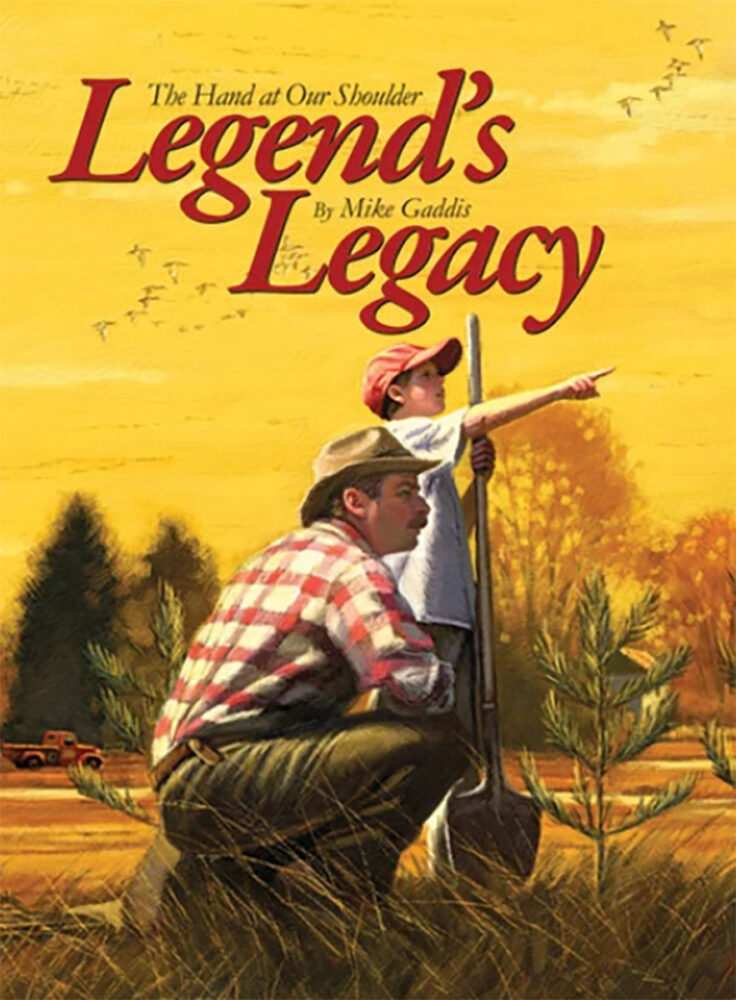

Legend’s Legacy stands unparalleled as an affecting commemoration of the most endearing aspects of our sporting traditions—an inspiring tribute to those who cared, who taught us then and guide us still. Buy Now

Legend’s Legacy stands unparalleled as an affecting commemoration of the most endearing aspects of our sporting traditions—an inspiring tribute to those who cared, who taught us then and guide us still. Buy Now