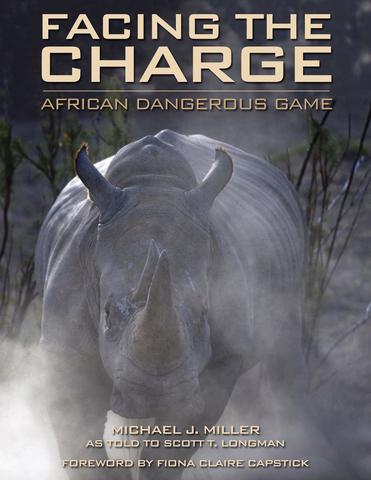

The conclusion of a chapter from Facing the Charge, a safari book featuring adrenaline-fueled tales of big-game hunting. Read Part One by clicking here.

Against the preceding quiet, the .375 H&H went off like an artillery piece. It acted like one, too. The bull dropped as though his legs had turned to pool noodles.

I cycled, hard, and reacquired. The grass was tall enough that there wasn’t a shot at the downed bull, but Atlantic City wasn’t taking any odds on what his two friends were going to think about this. Indeed, there’s plenty of precedent for buff acting like the Gotti family when one of their own gets whacked. I remained acutely aware that a buff with a purpose can cover 15 yards a second, and we were at most 40 yards from them.

To my happy amazement, they didn’t seem to think much of anything. They looked languidly around.

But not so the downed bull. He sprang back up like a toaster Pop-Tart. Before he could convert that rally into something more directed, I whacked him again, in pretty close to the same place. Again, he dropped as if legless. I topped off quick, got back in battery, and went back to scrutinizing his friends, who remained astonishingly disinterested in the proceedings.

Back up came the Pop-Tart.

Every time he sprang back up, things were looking worse. First, it meant that the downed bull had the full load of adrenaline in him. And every time I had to whack him again, it meant he had another opportunity to figure out where the rounds were coming from and decide to take umbrage. Likewise, the fact that his compadres hadn’t thrown in with him yet was absolutely no comfort. They might have a change of heart at any instant. With all that pressing on my consciousness, I did the only thing I could do under the circumstances and hit him again, also through the boiler room.

Bang, down again, and sproing, this time he almost flew out of the toaster. All three were now looking around. And then they began to move.

After an instant of adrenal fire hosing, I realized that the movement wasn’t aggressive, and it wasn’t even toward us—they began a slow shuffle off to the east. Two deep breaths, one half out, careful careful careful careful sight picture, this time on the spine, track and slowly squeeze.

The fourth round off.

The next several moments have been seared into my neural net in the way that only severe and life-threatening shock can do. My first semi-coherent thought was: That buff is shooting back at us!

Shooting!

That CAN’T be shooting! It IS shooting. A LOT of shooting.

At US.

Rory figured it out first, as he put his hand on my shoulder and slammed my face into the deck.

“Far bank of the river! Terrs!”

My last look before getting a faceful of grass was of little winking flashes way across the Zambezi. Muzzle flashes. A whole real lot of muzzle flashes.

We figured out later that it was probably the Zambian African National Liberation Army, and they’d been waiting for dark to cross the river, but my shots had alerted them that we were there. They’d decided to compromise the crossing in favor of shooting us from where they were.

Winston Churchill once famously observed, “Nothing in life is so exhilarating as to be shot at without result.” What he didn’t note was that the exhilaration accrues on a per-shot-fired basis. Given that, I was then experiencing more exhilaration than would fit into 10 Downing Street. Whatever ZANLA’s many shortcomings as a military organization, it sure wasn’t their supply chain. Every single shooter in that tree line had full-auto capability, and every single user was employing it. And this wasn’t aimed, careful, five-round-burst kind of behavior. It was a heavy, sustained firestorm, a horizontal lead monsoon.

Flat on our bellies, Rory had been sliding and tugging me down to the back side of the small rise we had been on when I fired. It wasn’t much, maybe a couple of feet taller than the surrounding land, but from my dirt-kissing position, it looked like the Alleghenies. I emanated gratitude at it for existing. I wondered what I could do for it, like maybe box seats at a Cubs game. I mentally added it to my Christmas card list.

With its protective mass between us and the incoming fire, and perhaps because my visual cortex found itself severely underemployed, my brain suddenly snapped over to the sounds around us. The most striking thing about it was the cacophony of whip cracks as the something-twice-above-sonic rounds went by. There were untold dozens per second, each varying in intensity and distance. And then there was a second soundtrack of whirrs and hums and hisses, some very close in the air, some very close through the grass, and others coming from the south bank as the projectiles hit. And against all that, there was the distant third track of the muzzle blasts themselves, the cadence of any individual weapon lost in the madness of dozens of them.

As I slowly wrapped my head around that idea, I jolted up with a cascade of more cortisols than the worst ever I-slept-through-the-alarm-clock you’ve ever had.

“Where’s the buff?!”

Pro that he was, while I was genuflecting to dirt, Rory had kept his eyes up the whole time, and as I looked at him, I realized it.

I felt bad. Really bad. But I tried to make up for it by hurriedly topping off the Browning. Since he was watching primarily right, I propped up and kept eyes and muzzle left.

So, to briefly recap: Someplace, close by in the tall cane grass—but we didn’t know even remotely where—was a wounded and heavily adrenalized Cape buffalo bull. Likewise, someplace else quite close were two other bull buffalo that may or may not have decided to reduce us to phenomenal peninsular fertilizer. To our front was what appeared to be the entire Russian Army at Kursk. Overhead was their scything display of firepower, and behind us, our escape route was across 80 yards of water with crocodiles, hippos, and a bunch of things to give palpitations to the entire Atlanta Centers for Disease Control and Prevention staff.

None of that, as it turns out, was the actual problem.

All those problems were, at best, also-rans in the first annual Who-Gets-to-Kill-Mikey Contest. And the way I figured that out was the ground.

The earth was trembling.

Badly.

And getting worse.

For a fleeting instant my mind blurted, “Earthquake!” Of course, if anything, a good window-rattling earthquake would have been pretty helpful right about then.

Well, remember the untold enormous number of buffalo that we couldn’t find? It turns out that they’d all responded to the same deal offering a special on the peninsula. Now, in the face of the hailstorm of sustained automatic weapons fire from the north bank of the Zambezi, they were all checking out early.

Via a mass stampede.

Straight at our position.

Rory was phenomenal. He talked low and clear and hard and fast.

“We’ll get back up on the rise. Just as the first one gets to us, we’ll both shoot him on the spot. Buff don’t usually trample their own—they’ll part around him.”

I listened to this as if outside myself, the endocrinology of the brain’s response to threat overload having lifted me over the whole tableau, as if I were lounging in a reclining lawn chair tied to a bunch of weather balloons. Floating Me vaguely ruminated that a life plan that called for dropping a charging Cape buffalo at your feet so that the hundreds or thousands of others charging behind him wouldn’t tromp you was, honestly speaking, not the single best plan I’d ever heard.

But I think I instead said something like: “Right.”

Rory went on: “After that, we are going to have to use the gap between the two streams of the herd to run like crazy.”

Floating Me tried to envision this. My voice, unrelated to Actual Me, asked: “We are going to leave the cover of the downed buffalo to run with and between all the rest?”

Rory came right back.

“You’ve got it. See, as soon as we shoot the buff, the terrs will have a fix on us. Almost certain, they’ve had a fellow setting up their mortar in the last few minutes. So they’ll start dropping mortar-bombs on where we fire from. Or close enough to frag us, anyway.”

Then he turned, looked me in the eyes, and cut loose an energizing, impossible, magnificent, life-affirming grin. I will never forget it.

“It’ll be a lark. Not all that far to the water.”

We edged up on the rise and could see the motion ahead now, violent whipping and dropping of the grass, then flashes of snouts and horns and bosses, very black in the long light against the grass, all at a thunderous dead run at us.

Safety off.

The entire ground was bouncing like the surface of a kettledrum. Or maybe it was just my cardio system.

Rory ready.

Electricity down my arms.

Cheek weld. Front sight.

Find THE one.

That one that one THAT ONE.

Two seconds.

And with that I witnessed, with bright blazing disbelief, the single most gratitude-inducing, relief-flooding, staggeringly welcome thing I had ever seen.

Twenty yards in front of us, the herd had parted.

It was as if there were an immense, invisible zipper tab in front of us, driving forward at ultra-high speed, as the two sets of separated zipper teeth flew by us on either side.

We later guessed that there were two reasons for the parting of the herd. First was that the area we were on was actually a floating bog with no real solid land underneath. I’ve since learned that things that weigh 2,000 pounds prefer solid land. The second issue was the small rise we were on. Apparently, even stampeding Cape buffalo recognize the path of least resistance. They hammered by like the Union Pacific Omaha Express, snorting and pounding and crushing, in what seemed like a thousand-boxcar blast.

The brain under any kind of stress like that is a radically poor timekeeping mechanism. My most conservative estimate is that it took 18 hours for them to go by. But finally they were past us. One side of the parted group wrapped back along the inside shore of the peninsula. And to my amazement, the other half went hard right and wrapped down to the river’s edge, actually heading back into the danger zone and closer to the far bank. By this point the firing had stopped, but it made me question the stories of buffalo intelligence.

Rory and I looked at each other, and Floating Me slowly settled back into my corporeal self. Based on how my wide-eyed face felt, I must have looked like a high-voltage owl.

He grinned. Life affirming, big, confident beyond the circumstances.

“Well, you’ve clearly been tipping the vicar, then, haven’t you?” Slapping my shoulder: “Worry about trying to recover your buff tomorrow. Let’s get out of here.”

Still achingly aware that my buff might not so much be in need of recovery as in need of further perforation, we slowly worked our way back down to the water. In my adrenal-crazed state, I regarded the water with even greater apprehension than when we’d first crossed it. But the known danger behind kept me from standing there thinking about it.

It was cold. I focused again on two things: trying to keep my strokes smooth to avoid the chopping vibrations that might get a croc all hot and bothered, and keeping my rifle out of the water. As before, I held it by the grip, safety off. If one of the prehistoric things grabbed me, I figured I had half a second in which to try to change his vote.

We finally reached the inner bank, and I clambered up it, soul-yearningly grateful to a lump of dirt for the second time in an hour. I controlled the muzzle and snicked the safety back on.

We pushed through the bush and then out into more grass. Tanya saw us coming, which was good, as it would somehow be my luck to survive all that and then get vaporized by my own police-issued rifle. I walked the final 20 yards to her.

I was exhausted, soaked, chilled, triumphant, abraded, grimy, exhilarated, disbelieving, thrilled, bruised, and, ultimately, transformed. The day had literally rewired my brain, and it was so good I couldn’t find words to begin to describe it to her. I opened my mouth to try—and she stopped me before I could even draw breath, her tone blistering.

“You are unreal!”

It so blindsided me that all I could do was verbally flop around like a gaffed carp.

She pulled a full-on charge.

“You stood right here and told me that it was okay to leave me here because you’d just be a minute and all you were going to do was shoot one buffalo!”

I think I started to nod before she cut me off with a hand gesture.

“Well, I heard you! I heard the whole thing! You must have shot a thousand of them!”

I turned to look at Rory. He and I made eye contact. It took maybe two seconds for the full implications and irony of it all to set in for both of us. I started the laugh, short and clipped, almost choking, at almost the same instant he did. We saw one another’s faces, and the laugh swirled and grew and gained momentum, a dust devil becoming a microburst becoming a tornado becoming a National Weather Service emergency, booming and rising, loud enough that it must have carried all the way to the far bank of the Zambezi.

In addition to adrenaline-fueled tales of big-game hunting, Facing the Charge details how death was a constant companion on safari in the form of terrorists, quicksand, malaria, and witchcraft, among other threats. It also analyzes how ivory traffickers have devastated the elephant population, examines the everyday hardships of life in Africa, and pays tribute to the men and women who have make Africa home. Shop Now

In addition to adrenaline-fueled tales of big-game hunting, Facing the Charge details how death was a constant companion on safari in the form of terrorists, quicksand, malaria, and witchcraft, among other threats. It also analyzes how ivory traffickers have devastated the elephant population, examines the everyday hardships of life in Africa, and pays tribute to the men and women who have make Africa home. Shop Now