Big fish, big fish on the end of his line! Oh Christ, what had I done?

I used to see old Artemis Hovle now and then as he slowly tapped his way along East Water Street, his white cane exploring the uneven surface of the brick pavement between the Post Office and Frenchy Coiner’s barbershop at the corner.

I would always speak to him and, now and then, he would return my greeting with a feeble wave of his free hand. But more often he would pass slowly on, seemingly lost in thought as he followed his cane on to O’Rourke’s store on the village square.

But one morning, as he stumbled on an overturned brick and seemed to be somewhat confused, I took hold of his arm and eased him into safer going. He was a slender, stooped little man with a pale and deeply-lined face. “There, that’s better, Mr. Hovle,” I said. “Seems to me the town should be doing some repair work, don’t you think?”

“Yes, yes, thank you so much. Oh,” he said in a high-pitched voice, “It’s Mr. Greenacre, isn’t it? You work for Josh Saulter up at the trout hatchery on the North Branch of Barkers Brook, don’t you? How is old Josh? Kin to my long-dead wife, you know. Haven’t seen him for years. Haven’t been to the hatchery either, not since I lost my eyesight. The branch used to be full of fat little brookies but I suppose they are all caught out now. Nothing there now but rainbows you fellows dump in. You’re not a fisherman so I suppose it doesn’t matter to you. What a pity, hatchery workers seldom go fishing, fly fishing, that is.”

“Oh, but you couldn’t be more wrong,” I said. “I fish every chance I get. I tie all my own flies and own more fly rods than I should. One of the reasons I work at a hatchery is so I can be near good trout water.”

It took the old man a few seconds to digest this. Then he nodded his head and suggested we sit somewhere and talk fishing for a while.

It was a bright, warm morning, and I was in no hurry so I took his hand and steered him across the square to the village green. I found an empty bench. “Here we are. We can sit right here,” I said.

He eased himself down on the slatted wooden bench and patted the seat beside him. “Here,” he said, “sit on my right. I don’t hear so good on the left.”

I sat down and he took off his shapeless gray hat and ran his fingers through his sparse white hair. I could see several snelled wet flies stuck in the heavy felt.

The old man leaned back and seemed to relax. “Sun always feels so good this time of the year. There’s bound to be a good fly hatch later on, don’t you think? Hendricksons probably, though it is a mite early.”

A thin smile crossed his face. “Now, Mr. Greenacre, let me tell you something interesting. Your voice sounds very much like Ed Hewitt’s. You know who I mean, Edward R. Hewitt. Used to live over on the Neversink River in New York, you know. He was the fellow who wrote so much about trout and salmon fishing and was always experimenting, always trying something new. Well, your voice has the same nasal quality. I’d know it anywhere. Ed had a big nose, big and red as the belly of a brook trout. Used to blow it all the time. Sounded like a damn foghorn, it did. Hell, it would even put feeding trout down if they was close by. Here, let me have a look at you.”

The old man leaned toward me and his pale, spidery hands touched my face. His fingers were slender and cold. He ran his hands along the bridge of my nose, into the sockets of my eyes, around my mouth and along my chin. “I knew it, I knew it!” he cackled. “You and Ed could be brothers, though it seems to me you’re a mite better looking. Died way up in his 90s, he did, just a few years after I lost my eyesight. Tell me one thing, Mr. Greenacre, is your nose red? It felt kinda red, you know.

“Ed used to come over and fish every year, usually about this time or a bit later. He was usually by himself, but one time he brought Mr. LaBranche along. They really didn’t fish very much — just sat around and argued about fly patterns and such.

“Barkers Brook was full of browns in those days and some of them was pretty good size too. And we had some great fly hatches … March Browns, Hendricksons, Cahills, Green Drakes. You name it, we had it.

“Now Hewitt, he was a real brain, that man. Why he would be out there from sunup til dark experimenting and blowing his big red nose. Oh, but he took lots of fish too. He always called Barkers Brook the Dogwater. And the name sorta stuck. All the old timers call it that. Dogwater, yes, just Dogwater.

“You know, it makes me want to cry when I think about those great days we used to have on the Dogwater. All the fish then was stream-bred, just brownies and a few natives. Oh, I suppose there are a few of them left, but mostly what I catch are your little hatchery rainbows and they don’t take a fly very good.”

“How in the world do you manage to fish with a fly?” I asked.

“Well,” the old man replied, “I have had to give up a lot of things since I lost my eyesight, but flyfishing isn’t one of them. By dammit, I fish some most every day or night; makes no difference, middle of the day or midnight, if I feel like fishing I just get up and go. Don’t catch much but, hell, it’s better than blowing my brains out. Only time I can’t fish is when the wind’s blowing. Tangles my leader and line.”

I glanced at the frail, stooped figure beside me … at the pale, drawn face and marveled that this relic of a once vital person could continue to maintain his enthusiasm for fly fishing.

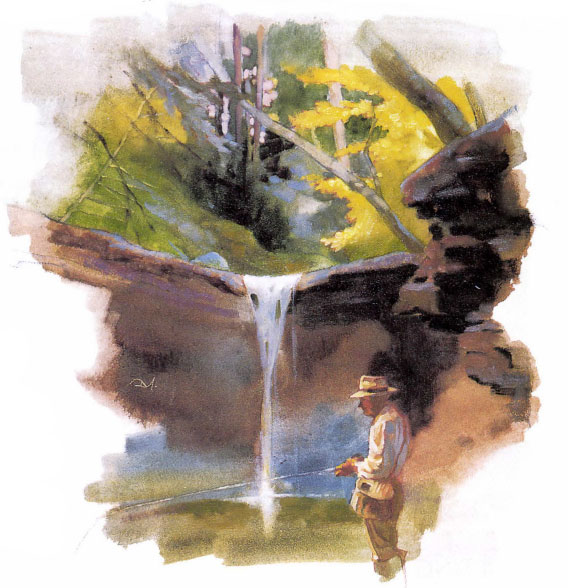

“Well sir,” he said as if sensing my disbelief, “it’s not easy, not easy at all. My home is almost on the banks of the Dogwater. It’s the old Haver saw place on Spartus Road right where the stream comes out of the gorge and falls over that big limestone ledge and comes into what we call the Ironstone Pool. You know where I mean don’t you?”

Forgetting his sightless eyes, I nodded an affirmative, then said, “Yes, it’s a lovely spot and the run at the tail of the pool looks great. But I’ve never fished it. Can’t. It’s posted, isn’t it?”

The old man tapped his cane sharply on the ground and his voice became shrill. “Well, I had to do it!” he said defensively. “It’s the only place I have to fish. Otherwise, those bastards from town would be in there with bait and clean it out. I own half a mile up along the Dogwater, clean up to the Clover Mountain Road. All that is open. You can fish it any time.

“Oh, Ephie and I have it fixed up pretty good. I can put a fly most anywhere I want in the pool except up at the top where there’s a big rock overhang. I figure there must be a big old brown holding up there and I aim to get him someday if he ever moves down.

“Ephie’s my daughter. Only child. She never married and I doubt she ever will. Old Ed Hewitt was here the day she was born. Born right in the middle of the damndest Green Drake hatch you ever saw. Ed said the flies was so thick he couldn’t hardly fish. Caught only a couple little browns. I couldn’t fish that day on account of Ephie being born and her poor mother passing away only a few hours later. I was right busy for a day or so, I tell you. But I did catch the spinner fall a couple days later and, boy, did I take some nice fish?

“It was old Hewitt who suggested I name her after the Green Drake. He said the scientific name of the drake was Ephemera guttulata. So I named her Ephemera. But I call her Ephie. Pity she never took to fly fishing herself. But she’s been a big help anyway, particularly after my affliction took me.”

I knew Miss Hovle slightly and thought her a pleasant woman but no beauty. No wonder she was single. With a name like Ephemera it would take a pretty desirable woman to find a husband.

Mr. Hovle chuckled. “I know what you’re thinking. No, her middle name is not Guttulata. It’s Haversaw, after her mother’s family.”

Ephie’s the one who started me fly fishing after I lost my sight. I would have given up without her. But she kept after me, an done day she rigged up my 9-foot Orvis Battenkill with a double taper line and a short leader with a loop on the end. Then she marked off 10-foot intervals on the line with dabs of cement so I could tell how far I was casting. I use snelled flies so I can change them easy. They’re simple patterns and I keep them at different places on my hat.

“Then Ephie strung a cord on posts all the way from the back door to the water and then on around the westside of the pool. She put some boards on the edge of the water for markers so I can stand on them and know where I am. I have the whole place layed out in my mind just like a map. When I feel like it I just step out the kitchen door, grab the rod and head for the Dogwater. Night or day, it doesn’t make any difference to me.”

In my mind’s eye I could see the old boy out there casting away in the middle of the night and asked if he ever caught many trout.

“No, not many. But I keep on trying. There isn’t much else for me to do and maybe sometime I’ll hook that big old brown I know must be up there in the head of the pool. Let’s see,” he mused, “I’ve caught six fish so far this year, but two of them was chubs so they don’t hardly count. All the rest was rainbows about nine inches long. Hatchery fish, all of them. Their fins was kinda wore down. They must have drifted down from upstream.”

“No, not many. But I keep on trying. There isn’t much else for me to do and maybe sometime I’ll hook that big old brown I know must be up there in the head of the pool. Let’s see,” he mused, “I’ve caught six fish so far this year, but two of them was chubs so they don’t hardly count. All the rest was rainbows about nine inches long. Hatchery fish, all of them. Their fins was kinda wore down. They must have drifted down from upstream.”

The old man made a couple of imaginary false casts with his cane. “I miss a lot of fish because I have to strike by feel or sound. Sometimes, when it’s quiet, I can almost tell when a fish is gonna take. It’s like it comes up and sorta breathes on the fly.”

“How did you know the fish you caught were rainbows?” I asked.

“Rainbows? Well, they feel kind a brittle and hard. Now brookies are like velvet, wet velvet. Smooth. Soft. And browns? Well they just feel brown, sort of brassy maybe. And they smell different, not bad, just different. But I haven’t caught a brown this year or a brookie either. Only rainbows. All with bad fins.”

A few days later I drove along Spartus Road, past the Hovles’ small brown house and up the hill. I parked in a clearing and walked through low brush until I could seethe Ironstone Pool. Shreds of mist layover the water and a thin, cold drizzle had set in. Artemis Hovle was standing at the edge of the water about thirty yards from his house. He was casting methodically, then retrieving his line slowly. He was wearing a long raincoat.

After a few minutes he reeled in his line and took hold of the cord that was stretched along the edge of the pool. Then he crept slowly along to another position, paused for a few seconds, stripped line off his reel and began casting.

As I walked slowly back to my pickup an idea began to take shape in my mind. Why not, I thought, give the old boy some real trout to fish for, put a little excitement into his fishing efforts?

At that time, we were phasing out our seven-year-old brown trout brood fish and had some large males to get rid of. They were beautiful fish, perfect in every respect except for missing right pelvic fins, clipped off when they were fingerlings in order to identify them as breeding stock. There was no reason why I couldn’t slip a few of them into Ironstone Pool. No one would know, least of all, the boss, who lived six miles away and wasn’t likely to notice the fish were gone anyway.

I waited for the right time. Several days later the weather turned cold and a strong wind keened in from the north. Around midnight I slid a tank on the bed of my pickup and filled it with water. Then I netted four big struggling male brown trout out of a pond and dumped them into the tank.

It was only a 20-minute drive to the hill overlooking Ironstone pool. I cut my lights and drove slowly through the sparse undergrowth until I was about 50 yards from the water. The moon was low. The Hovles’ house was dark. Except for the wind in the trees and the muted roar of the brook, all was quiet. I carefully dipped the browns out of the tank and carried them to the edge of the pool. I slipped them into the dark water. They swam quickly away.

The following morning, I left the hatchery with a load of fingerling rainbows for a stream in the northern part of the state. The truck broke down on the return trip and I didn’t get back until the next day.

So it was Thursday before I got to the Post Office. I was coming out of the building reading a letter from my sister when I saw Ephie Hovle getting out of her faded Buick. Anxious for word of her father I walked toward her. She was dressed in black. Her graying hair was plaited and wound tightly around her head. “How is your father?” I asked.

She put her hand on my arm. Tears, like raindrops, welled up in her deep-set eyes. “Then you haven’t heard? Father’s gone. Passed away night before last.”

What could I say? I fumbled for words and finally managed to say something about the passing of a great angler and that Artemis Hovle would be missed by his fishermen friends. Meaningless words.

Ephie turned away for a moment then dried her eyes with the back of her hand. “If Father had to go, I suppose he went the way any fisherman would want to go. The poor man died with his pole in his hand, and a great big fish on the end of his line.”

Big fish, big fish on the end of his line! Oh Christ, what had I done?

Ephie continued as I stood half in shock. “You see, I got up in the night and looked in on Father. It was maybe two or three o’clock. He wasn’t there. But I didn’t think nothing of it because it wasn’t all that unusual. He would fish any old time just whenever the notion took him. So I went on back to bed and didn’t get up until it was good light. I peeked into Father’s room then and he still wasn’t there.

“Well, I began to fret. So I called out and when he didn’t answer, I looked out the back door. His pole was gone and so was his boots. So I pulled on a coat and ran out in the rain. I found him laying there on the bank with his head clean under the water.”

Ephie suppressed a sob and continued. “Well, I waded into the water and grabbed him by the hair and tried to lift him but he was stiff and I couldn’t budge him. So I got out of the water and took ahold of his legs and pulled him up on shore. His eyeglasses was gone and his old blind eyes was rolled back and as white as milk.

“Even after he was up on the shore he still had ahold of his pole and the line was wrapped around his wrist. I prized it loose when I realized there was something on the end of the line. Well then, I just pulled it in. On the end of the line was the biggest brown trout I ever seen. So I threw it back up on the bank .It thrashed around in the bushes for a bit then went quiet.

“I called Dr. Bedvold and he came out and had a look. Then he called the funeral home and they took Father away. Later on the doctor called and said his heart had just given out — couldn’t stand the excitement, he said.

“Well, that’s all there is to it. We will bury him tomorrow up at Memory Gardens on Connerys Mountain. That’s where Mama is buried, you know. Services will be at one at St. George’s Chapel.”

I didn’t say a word. Couldn’t. I turned and walked slowly away. For a while I sat on the bench where Artemis Hovle and I had talked of trout fishing and the Dogwater and Ed Hewitt. It seemed a long time ago.

Only a few people braved the driving rain when they lowered all that was left of Artemis Hovle into the earth. I stood back and took shelter under a leaning spruce, while Josh Saulter stayed beside Ephie under a wind-whipped awning. Later, as I turned to go, Ephie spotted me.

“Come to the house,” she said. “Come on up. There’ll be a bite to eat and we can talk about trout fishing and about Father.”

I approached the Hovles’ house with a heavy heart and a deep sense of guilt. The rain had stopped. Mist, like a shroud, hungover Ironstone Pool.

Ephie let me into the tiny living room. A dozen or so people were gathered around a scarred oak table on which lay the remains of a gigantic male brown trout, its head and tail extending far beyond the confines of a china platter. It was obvious that the fish had been poached. Its skin had been peeled off and folks were picking meat off the ribs and popping it into their mouths. The sight almost made me ill, and I turned away, only to find Ephie at my side.

“Help me turn the fish over, Mr. Greenacre,” she said. “There’ll be plenty more meat on the other side.” She put two large wooden forks in my hands. “Here, you roll it over, I’ll hold the platter.”

Reluctantly, I slid the forks under the fish, managed to raise it a few inches, then heaved it over on the platter. It was the first time I had had a good look at the entire fish. Every fin was intact! None was missing! This was no hatchery trout. This was a wild, Dogwater-bred brown trout. Old Artemis Hovle was right when he said that there was a big old brown trout holding up at the head of Ironstone Pool. Thank God. Oh, thank God!

I dropped the forks and with my fingers, pried off a big chunk of firm flesh. I put it in my mouth. It was the best damn trout I ever tasted.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 1990 Sept./Oct. issue of Sporting Classics.

Delightful tales of hunting and fishing, family, friends, dogs, and precious time well spent. Nationally recognized and award-winning writer Jim Mize captures the true essence of sport and living life to the fullest in this collection of stories about his outdoor escapades. In tales spanning more than five decades, Mize invites readers into carefree days hiking through the Colorado Rockies with a fly rod and leisurely casting poppers to bluegill on small southern ponds. Mize’s humorous stories entertain and return readers to their own turkey hunting or creek-fishing excursions. Black-and-white drawings from artist Bob White illustrate stories filled with laughter, quiet contemplation, and wonder. Buy Now

Delightful tales of hunting and fishing, family, friends, dogs, and precious time well spent. Nationally recognized and award-winning writer Jim Mize captures the true essence of sport and living life to the fullest in this collection of stories about his outdoor escapades. In tales spanning more than five decades, Mize invites readers into carefree days hiking through the Colorado Rockies with a fly rod and leisurely casting poppers to bluegill on small southern ponds. Mize’s humorous stories entertain and return readers to their own turkey hunting or creek-fishing excursions. Black-and-white drawings from artist Bob White illustrate stories filled with laughter, quiet contemplation, and wonder. Buy Now