There are some who can live without wild things, and some who cannot . . . This is a story for those who cannot. In 1927 Crazy Ernie, Kid Al and my dad won a hunting shack in a poker game and lost their hearts to a swamp.

In a remote northwoods clearing stood a sagging cabin with a leaky roof and holes in the walls big enough to throw a cat through. An equally attractive outhouse and a rusty old wood stove completed the accommodations, which were surrounded by a quarter section of mostly logged-over woods and swamp. Kerosene lanterns provided lighting, and water was hauled from one of the many springs. Interior camp walls were decorated with deer antlers, bear skulls, decaying grouse tail-feathers and various moldering old hides. It was nice. In fact, the boys were so impressed with their swanky new hunting lodge that they christened it “The Estate.”

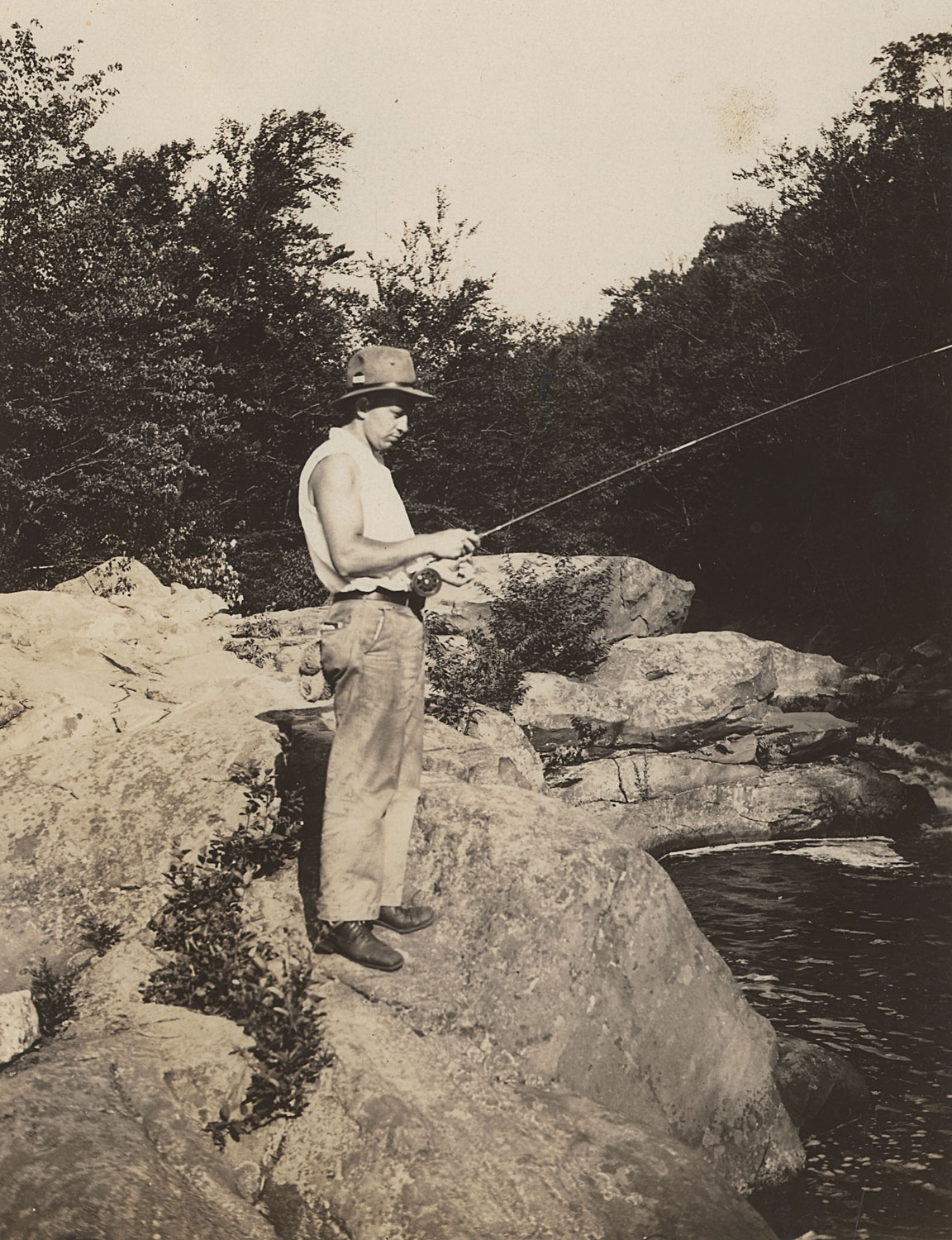

Just reaching The Estate was a formidable challenge in those days. After negotiating their Model T over many miles of rutted logging roads, the final obstacles before reaching camp were the swift trout waters of the Big Paunacussing. They were able to repair the log footbridge across the stream, but it was only strong enough to support one person at a time. All inbound camp supplies and outbound venison required a punishing haul across the precarious footbridge.

From left: Ernie, Al and Paul, circa 1930.

Many work holidays were held during the summer, and the highlight of these were blueberry-gathering and fishing for brook trout. Ernie, the top Estate chef, proclaimed that the best fish in the world were fresh wild brookies fried in bear grease. Rendered bear grease imparts a subtle woodsy flavor that complements nature’s sweetness.Squirrels, porcupines, pack rats and bats were more or less evicted from the camp, although the mice continued to love the shack just as much as the hunters. Old mouse-infested bedding was burned, and new mattresses were made of ticking stuffed with corn husks – the kind of mattress that crunched every time you moved on the creaky old beds. Eventually, major repairs were finished and other details forgotten, because new adventures now existed beyond the boundaries of the cabin.

For example, bird hunting was considered to be drop-dead amazing, with ruffed grouse at the top of the list. One of my favorite fantasies is to be trapped at The Estate in a 1920s time warp with my favorite shotgun, my faithful dog and several cases of shells. Of course, I would be forced to stay during the entire grouse and woodcock season.

My father, Paul, told stories of whitewashed swampy thickets and alder flats swarming with woodcock during migration flights. And the dense underbrush that grew up after logging and fires was producing incredible numbers of grouse. In my mind’s eye I can see him framing yet another grouse between the hammers of his ancient 12-gauge Ithaca double.

When we hunted there in later years I was always curious that he would rarely shoot – unless an easy, straightaway shot presented itself. Dad explained that bird numbers were so high and he was so frugal with shells that he was ruined by his market hunting uncle’s habit of taking “only shots to make meat.”

Although, deer and bear numbers were considered fair to middlin’ by Estate standards, populations were still on the rise following a low point around the turn of the century. After a hard week of hunting in 1929, only a few deer and no dirty rifle barrels were reported. Only Ernie had seen deer, and he had spent the week swaying in the wind on a rickety tree stand. Adding to his unorthodoxy was his insistence to hunt with a long-bow – this, before archery seasons had been invented and everyone else was carrying high-powered rifles.

Tatters of moonrise and light snow sifted through the dark woods as the trio trudged back to camp late one evening. Breaking out of the black spruce into an opening, Crazy Ernie yelped “Jeez Cripes” as he pointed to fresh bear tracks leading into Spook swamp.

Energized by Ernie’s worst cuss word, Al and Paul hurried over to examine the giant, moonlight-filled tracks. There may be other Spook swamps around the country, but it would be a fool’s errand to search a map for this place, as it lies only in the minds of those who know it well.

Al tries his luck for native brook trout from the rickety old footbridge leading into The Estate.

More compelling than the plans laid that night by our mighty hunters was Al’s recounting of the legend dating back to the Iroquois:

The story held that a young hunter crossed fresh bear tracks leading into the nearby snowy swamp in the fall of 1630. Needing to fill his family longhouse with winter meat and precious fat, the Iroquois brave took up the track with his longbow and a full quiver of arrows. After not returning to his camp, the tribe formed a search party. Tracking skills defined these hunters’ lives, yet only bear tracks were ever found leaving the swamp. Circuitous miles of bear tracks finally vanished into the Big Paunacussing River.

A century passed into the fall of 1730 when a middle-aged Iroquois hunter with an irresistible urge to be in the woods was bound for the same swamp with his flintlock musket. Where a solitary set of bear tracks left the swamp, members of his tribe eventually found a very old Iroquois longbow and a quiver full of arrows. The hunter and his flintlock could not be found, and the search was called off after repeated attempts failed to find the trail lost in a prolonged blizzard.

In November of 1830 an aging chieftain was weary of responsibilities in a world he no longer knew. Wanting fresh venison but needing the peace of the forest, he followed fresh bear tracks into a new world. His puzzled tribesmen later found only a century-old flintlock musket next to oversize bear prints leaving what was now called Spook Swamp.

Ernie told Al that he and his legend was “full of more crap than a Christmas goose,” but to me the old legend rings true. The Iroquois knew. In this world of continual change, the bear and swamp keep reminding us that what remains constant is our inexorable longing for wild things.

The Iroquois called their oneness with nature, orenda – the lasting essence that permeates all things and relates all to one another. As the noted professor and hunter J. Ortega Gasset observed, “That which never changes, always permanent is nature.”

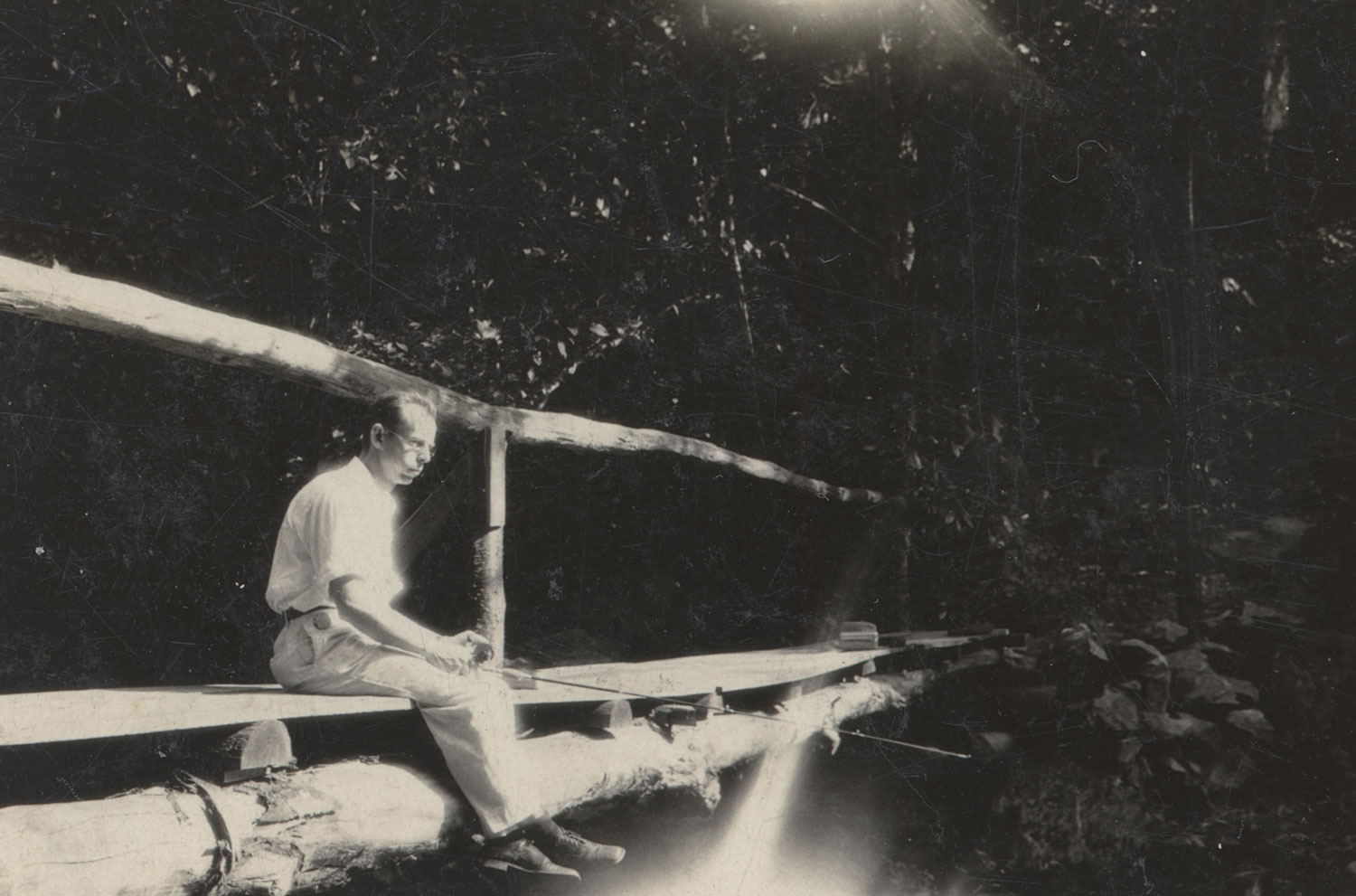

Paul fly-fishes in the stream behind the cabin.

Meanwhile, in November of 1929, Ernie, Al and Paul are readying for their bear hunt. Drawing straws, it’s decided that Al and Ernie will post at likely game trails leaving the swamp, while Paul dogs the tracks. The hunters, wearing their traditional backwoods tuxedos – black-and-red plaid Woolrich – join with the spruces dressed in their wedding veils of snow.

Arriving at the swamp they each know their place. Halfway through the frozen swamp, dad hears the bear crash out of its nest on an island tangled with dense white cedar and downed timber.

Big-bellied clouds are spitting snow as a rifle cracks once, then again and again on the far side of the storm-shrouded swamp. Paul smiles, anticipating the upcoming story. He follows the bear tracks out of the swamp, but on this day no ancient weapons are found. Instead, Al’s .38-55 Winchester is sitting on one end of a log with Al on the other end wearing a dazed expression and only one boot.

Crazy Ernie, clad only in red long johns, is singing and dancing in what appears to be some sort of ritualistic celebration around a big bear.

Apparently, Ernie fell through the ice, soaking himself to his chest. With a waterproof match, some spruce pitch and trembling fingers he started a warming fire. He was only partially dried when Al started shooting.

In the ensuing excitement, Al tangled his feet in some roots hidden in the snow and badly sprained his ankle. The unlikely bear hunters, barely out of high school, had bagged a real trophy. Al might have weighed 130 pounds soaking wet, but the bear weighed three times that.

Several hours of backbreaking labor produced winter meat for three families, a handsome bearskin and an ugly swollen ankle for Al. The powerful but amiable Ernie volunteered to carry Al piggyback, while my Dad juggled two rifles, a longbow and a backpack on their grueling hike back to camp.

That night the trio held council around the woodstove, Al soaking his bad ankle in a dishpan of snowmelt water, Ernie and Paul discussing bear-packing. Hiring a horse and sleigh was briefly considered, but since the closest house was about 18 miles away as the crow flew and 30 as he walked, they resolved to take care of it themselves.

The next day, using a crude homemade sled and with Ernie and Paul serving as horses, they brought the bear to camp.

The camp’s Model T was used for toting the hunters’ bear and deer back home

Several flat tires, broken tire chains, a roll of baling wire and two days later the hunters finally made it to their homes some 120 miles to the south. Floorboards needed to be removed, and the brake bands tightened on the Model T every few miles coming out of the hills. Dad grumbled that he spent more time under the Model T than in it. Al grumbled that he had to ride all the way home sharing the back seat with a bear. Ernie complained about the sleet, since it was his job to run the hand-operated windshield wipers. With no real heater and the side window curtains keeping out only some of the whining of cold wind, the men suffered the entire trip. The bear meat, however, was in excellent shape, and all agreed that they couldn’t wait to do it again!

The last time I saw The Estate was about 1970, shortly before I moved away from the area. Ernie was settled in a rocking chair on the porch wearing his trademark red long johns, eating a baked bean sandwich and holding forth on camp history.

By early afternoon Paul, Al, Ernie and friends had once again graced the game poles with bucks and bears. Beautiful brookies, browns and rainbows had risen once more to the fly, while countless others were left swimming in the strong currents of Ernie’s mind. His stories filled the air with ducks and geese, bald eagles and ravens.

The wild corridor connecting Paunacussing River bottomlands with state forest uplands was a refuge for both wildlife and hunters. At times this land may have even been a corridor between heaven and earth.

Ernie told about Al and Paul having life-saving sabbaticals at the shack in ’33, after taking financial beatings during the Great Depression. After being discharged from the army, Ernie spent all of 1946 at the hunting camp, mending his mind and body from the ravages of WWII.

The old woodsman was now living there year-round and was The Estate’s sole owner. Within easy reach was his .22 Hornet that he used to scare off coyotes and land developers, as this was the era when lovely area lakes and rivers were being girdled by monotonous rings of vacation-tract houses. Swamps and other wetlands were still being drained to bring more city into the wilderness. Ernie, however, held steadfast to his own vision – he had just applied for a conservation easement to protect the land forever.

Ernie, Al and Paul are now long gone, but the deep peace of the forest and its wild things still remain. Maybe Ernie wasn’t so crazy after all.