So long as I have a mind that thinks and a heart that loves, I will remember my brother Gary and the little creek valley that bore our footprints for a brief time when we were young. We were transients moving from one epoch in life to another, but the little stream and the woods and fields it drained live larger than one can imagine.

Through the vapors of memory, the mystic chords that tug at me from a period so long ago beckon our time spent in the out-of-doors. I came of age near the Ohio-Indiana line where the till plains flat as a skillet meet the hilly glacial moraines. Cornfields, pastures and woodlots checker-boarded the gentle undulating hills piled up by mile-thick glaciers.

Indian Creek, named for the ancient Adena earthworks along its course, cut sinuously through the straight-line right-angles of fence rows and narrow asphalt ribbons laid long ago over sections lines. The creek purled over the state line into Ohio and then immediately beneath a short truss bridge that looked like a steel rib cage of a large mammal. A few friendly farmers afforded us places to fish.

Gary and I landed everything from common shiners and redhorse suckers to creek chubs. I can still hear in my head the croaking sound a creek chub makes as it slipped through my hand. We wrangled from the roots of pale streamside sycamores, rock bass with red eyes too big for their face. Smallmouth bass taking off with a spinner were most impressive.

When I travel through the recesses of memory I always arrive at a singular recollection of a cool, early spring afternoon from a lifetime ago. I’d tired of fishing, not being able to draw a strike. My attentions turned to fossils entombed in creek stones littering the stream bed. Gary plowed on ever determined to catch something. He had a deliberate gait and how he ambled between pools showed his resolve that afternoon.

Gary pushed his glasses up once or twice as he looked down, threading his line onto yet one more lure. He laid a jig in a deep pool the color of root beer beneath bare box-elder branches. He felt a slow take and set the hook. His wet boots on smooth rocks sent him staggering. He tripped on a pewter-colored aluminum tackle box lying open that put him to the ground. To save face, I was to blame for the spill. I’d left the tackle box where he could step on it. We exchanged verbal jabs, and with a pair of pliers he wrinkled the tackle box back into shape so that it would close.

In retrospect our times together along Indian Creek and the hills that hemmed it were rather short-lived. The intersection of time and place permitted a little stream to make outsized impressions. All things come to us in seasons—and so they go.

My next season found me at Hocking College where I first endeavored to become a fish biologist. The old two-story brick house where I rented a room was an artifact of the former coal-mining industries in Ohio’s Appalachian Piedmont. What had housed an affluent family in the early 20th century during the mining heyday now kept rain off college students.

That March, 30 – some years ago, was exceedingly wet. Sleep didn’t come easy. Flat raindrops splattered the portico right outside my second-story window like nails splitting tin. In the pre-dawn dark a police officer visited my front door. He delivered news that made me dizzy with dread. I needed to call home right away. There had been a death in the family.

Backlit by a distant street lamp, rain poured down my neighbor’s kitchen window like thin drams of mercury. The dial on her dirty-yellow rotary wall phone spun torturously slow. The phone pulsed teh-teh-teh-teh-teh in my ear. The last number sent the call clear across southern Ohio. All of eternity compressed in the moment. The phone rang once. My dad, the man with a spine of steel, told me in a quivering voice that my brother was dead.

March is the cruelest month. It’s neither winter nor spring. But the coming season will leaven the pallor of that in-between time. Gray must yield to gold. The hills along Indian Creek made by a Pleistocene winter will be spattered colors akin to a candy box.

Here’s what I see. Thin sooty morning clouds lift off an orange eastern horizon. Yellow-breasted chats in the trees ceaselessly sing. The morning sun warms my face, and the air is damp with dew. Gigantic pale-green sycamores sewn into the banks lean over the pools as if they have a yen to see who’s fishing upstream. And there I am, atop a hill just this side of the Indiana state line looking down the valley to see my own teenage self. There’s the two of us. A smile is fixed on Gary’s face and there’s wet sunshine in his hazel eyes.

Gary ended his own life at a time when there’s still a lot of boy in a man. Left with a poverty of understanding, I tried to get inside his head. His cryptic note, the last words he scrawled before walking out the kitchen door offered nothing. Beneath the blue lines left by his hand is an answer that I have never found. I am resigned to say that some things are simply unknowable.

But here’s what I do know. Nature and humanity are not bifurcated—nature makes us human. And the past is not dead. That creek and its chubs and chats and sycamores that threaded through us transcend time and space—the living and the dead. Those waters where we tussled with sunfish still provide counsel. My brother’s death swamped the lives of those who cared about him, but love endures. His memory deserves perfect grace.

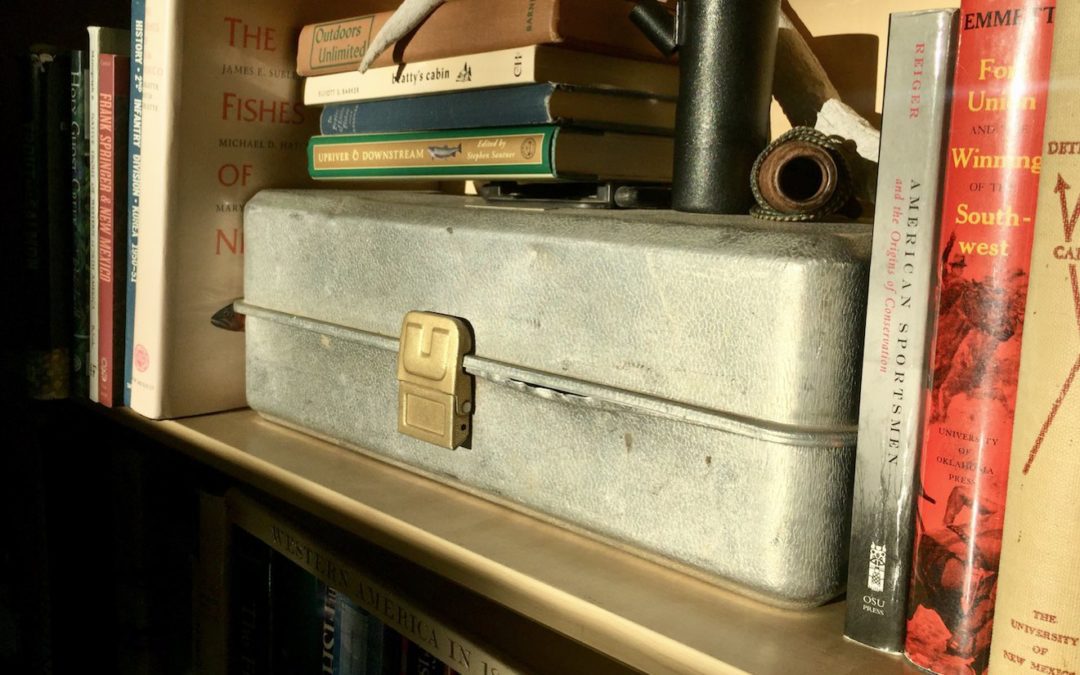

Gary lies at rest on the brow of a glacial moraine beneath muscular oak, maple and gum trees where forest birds fill the air with bright spring music. I still have the tackle box that he stepped on. It sits on my bookshelf with a few of my favorite things. It has the faint sweet smell of anise oil we put on lures thinking it would attract big fish. The trays have a few dry-rotted sunfish poppers, rusty spinners and scarred plugs. The keepsake is the bite marks from his pliers made that sacred day many years ago.