For Joshua Spies, it’s about payback.

Across the lonesome, windblown prairie of northern mid-America, locals know him simply as “the kid.” On this morning, the prodigal artistic son of Watertown, South Dakota, stands in his studio surrounded by six easel paintings, none of them completed, and he is feeling understandably distracted.

A big Mule Deer checks out his backtrail as he ghosts across a snowy hillside.

Joshua Spies has a flight to catch, bound ultimately for Nashville, though now his mind is drifting toward the memory of a frigid night spent on a mountaintop in Kyrgyzstan. Spies had gone to the former Soviet republic six months earlier with a sporting friend from Pierre, the state capital, who happens to be a surgeon. “It comes in handy to have a doctor along in case you ever get into trouble,” he says, though only half in jest.

The hunting buddies traveled to the other side of the world to stalk ibex and Marco Polo sheep, but found themselves bivouacked at dusk near the crown of a peak.

It was, after all, November.

They were cold — very cold — colder, Spies says, than any cryogenic deep freeze he had endured in his native homeland during the worst winter blizzards. The men had their guns with them on their backs, but their fingers and toes had gone numb.

“We were up there trying to hike through waist-deep snow with our local guide, attempting to cross from one side of the mountain to the other to find animals when night came,” Spies recalls.

In darkness, they made camp. “We crawled into our tent, put on every layer of clothing we had and huddled into our sleeping bags. And we were STILL cold.”

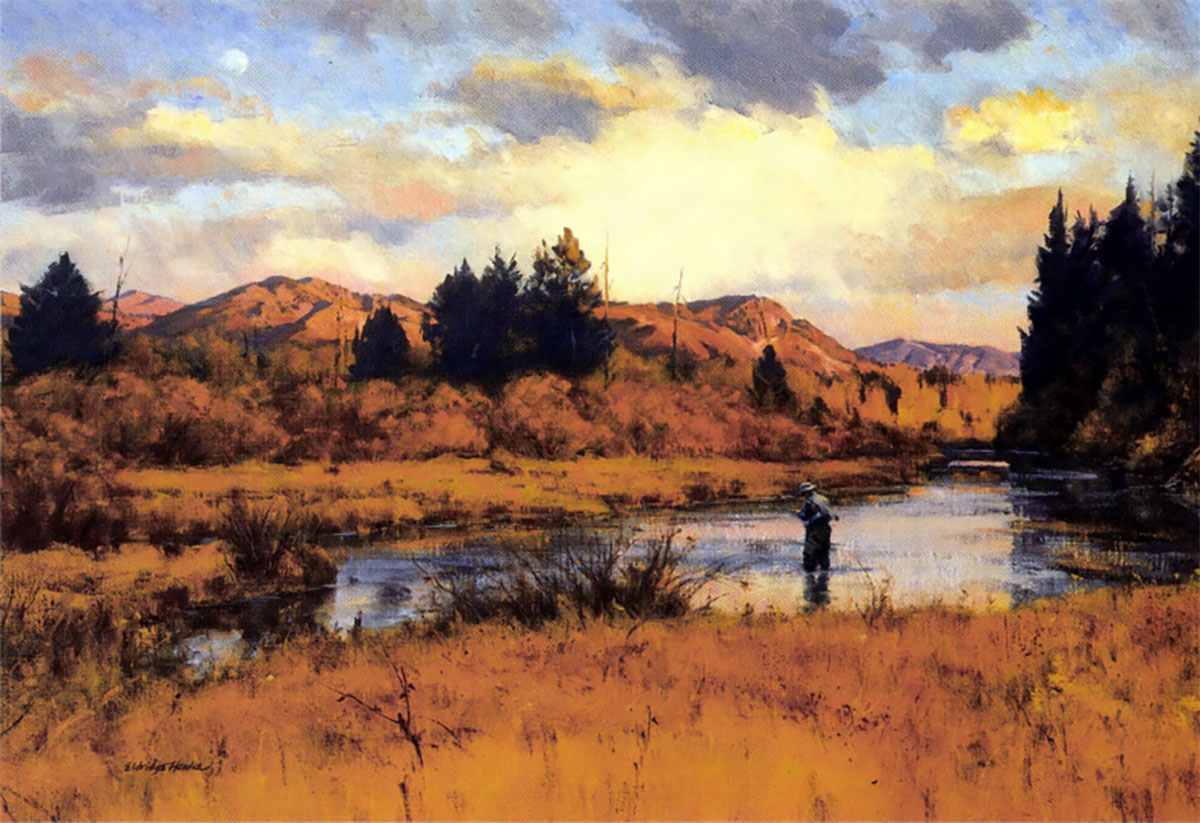

Joshua Spies’ captivating portrait of a whitetail buck,

entitled Autumn Glow.

Spies and the good doctor looked at each other. They were helpless.

“This kind of sucks,” Spies said.

“Do you regret coming here?”

“Nope,” the doctor shot back.

“Me neither,” the artist answered.

And then, the stark reality of the moment gripped them and the two friends started to laugh uncontrollably at how damned crazy they were; the lengths they had gone so they could enjoy the thrill of hunting in a place far beyond the usual ken of fellow pheasant and duck hunters in the potholes of Dakota.

Spies says he had to pinch himself at how lucky he was.

“Let me tell you that we used to think we were tough,” he adds. “We were decked out in thermal wear from Cabela’s. All our guide had on was a light jacket, pants and rubber boots.”

Back in his studio, Spies studies a photograph he took at sunset while on that distant mountain and he is attempting to recreate a warmer atmosphere, with a majestic animal portrayed inside the frame, to celebrate the adventure. It already has an eagerly awaiting collector.

Mara River Migration reflects the artist’s penchant for conveying a riveting sense of danger in

some of his paintings.

In this economic downturn, it’s smart to be bullish on wildlife artist Josh Spies. The “kid” who hails from the same small town that produced legendary sporting artist Terry Redlin and John Wilson — who won the federal Duck Stamp in 1981 — is indeed a boy wonder who deservedly, Watertownians say, has parlayed a simple passion for the outdoors into an international painting career.

“He’s become a hero to those of us who have watched him grow up,” says Diana Berns of Expressions Gallery in Watertown, a family-run purveyor of art that has been in business for more than 50 years. “Still, I would bet that 98 percent of the people don’t realize quite how well known he’s become. He’s not out there broadcasting his accomplishments.”

If ever one worries about the level of fresh talent that exists in wildlife art, moving up the ranks as replacements for the old guard that has defined the genre for the last half-century, look no further than the talented Joshua Spies. Like his predicament scenes of North American, African and Asian animals, in which he leaves viewers imagining their own outcomes to dramatic visual tales, Spies’ story has surprise elements built in.

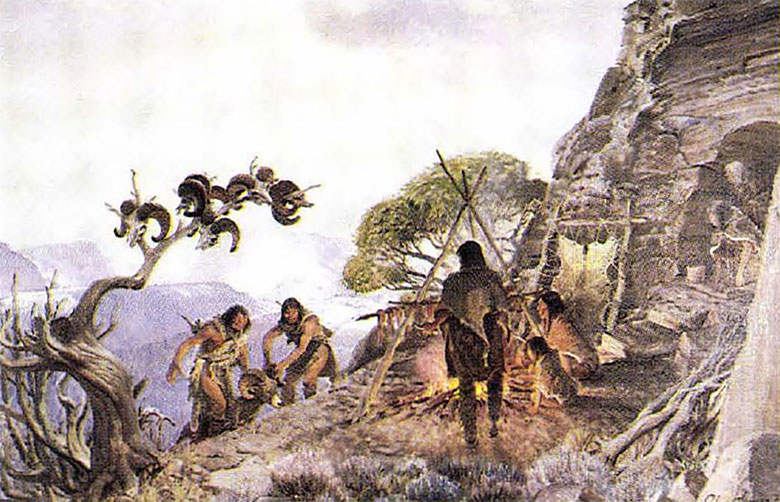

Spies traveled halfway around the world to hunt Marco Polo sheep. He took this magnificent ram deep in the mountain wilderness of Tajikistan.

On this day, as he pondered the direction he would take in six new paintings — and simultaneously plot six more taking shape in his head — his appointment in Tennessee involved a date with the United States Fish & Wildlife Service, honoring him at the Bass Pro Shops Outdoor World retail store for winning the prestigious 2009 U.S. Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp, better known as the Duck Stamp.

Now, with Spies’ name etched in history, he joins the company of other giants whose images have appeared on waterfowlers’ licenses, which have been used as a powerful conservation fundraising tool since 1934.

Interestingly, the last artist to win the federal with a depiction of a long-tailed duck was Minnesota artist Les Kouba in 1967, six years before Spies was born. Kouba, it turns out, had been an acquaintance of Spies’ granddad who owned three Kouba originals.

With ingratiating modesty so rare for someone his age, Spies responds to an attaboy by saying, essentially, “I still sorta can’t believe I won.”

Thanks to painting, Spies has a dog-eared passport that would have made Ernest Hemingway envious. Research trips, taken to hunt and gather material for his commissions, have led him to Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Spain and, with his father, Jim, to the Zambezi River Valley below Zimbabwe’s Victoria Falls where they pursued Cape buffalo and elephant.

Before that, Joshua and his wife, Heather, along with his dad and mother, Francine, decamped in Namibia. “I have adventure in me and the people who collect my work do, too,” Spies says. “It makes everything more intriguing and fascinating. Every painting I do is based upon something I’ve seen or experienced. “For those who cannot afford his original works, the artist has bucked the trend of bucked of sagging sales in the print market by collaborating with Greenwich Workshop on a line of affordable editions and launched his own line of giclee reproductions.

The artist’s painting of a long-tailed duck and decoy topped 300 other entries in the 76th Annual Federal Bird and Migratory Stamp Competition.

The only thing more striking than Spies’ diverse range of subjects is his ingenuity as an entrepreneur.

To believe that his motivation is all about commerce, Berns says, is to misunderstand the ambitions of the kid. In Watertown, when Spies isn’t painting, he’s appearing before grade schools discussing his trips and talking about the rewards of art, or giving away hundreds of prints to support a variety of charities, from the March of Dimes to the food bank.

“He’s pretty unaffected by his success, not full of himself as a young man could easily become. To the people around town, he’s still just Josh,” Berns says.” Heck, when a new image arrives back from the printers, he will swing by the gallery and ask us if we need any help framing them up.”

For Spies, it’s about payback. “When he was a teenager, a lot of people bought his paintings because they wanted to Support him and thought it was kind of cute that this kid was aspiring to become a professional painter. Little did anyone know,” Berns explains. “He just keeps getting better and you can see it happen from painting to painting.”

What Berns also appreciates about Spies is his loyalty. Although he’s been courted by galleries in major U.S. metropolitan areas and has influential collectors, he still values his local connections.

Spies grew up hunting pheasants, ducks and deer in the 1980s alongside his father. He received a degree in fine arts from South Dakota State University. Surprisingly, perhaps, when asked to identify an early influence, he does not cite any particular wildlife artist. He does point to the work of hyper realist painter Chuck Close, whose work he saw during a visit to the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. What Close’s gigantic canvasses taught him, Spies says, is the importance of making an immediate impact on the viewer. As for his approach to composition, especially in his landscapes, he mentions the ancient Asian painters who rendered animals and birds during the Southern Song Dynasty in China.

In college, Spies started entering state, national and international wildlife art competitions. He won the South Dakota waterfowl stamp contest at age 25. While still in his 20s, he began working with local chapters of Ducks Unlimited, Pheasants Forever and the National Wild Turkey Federation, making his original paintings available at fund raising auctions.

Zebras gather at an African pool in Waterline.

He eventually got involved with Safari Club International and started branching out to paint more scenes of big game and became an annual fixture in booths at the Dallas Safari Club and SCI conventions. He says his trips to Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are owed to friendships he made with proprietors of a Russian outfitting company who had a booth next to his at a Safari Club event.

The more that people have seen Spies’ work in acrylic on mason board, the more exponentially that word of mouth has spread and, in turn, Spies has used proceeds of sales from originals and prints to fund trips to Africa. Requests for commissions had him backed up for a couple of years, even before he learned that he’d won the Duck Stamp.

“It’s not that I don’t enjoy painting waterfowl. I do. I’m passionate about it,” he says. “It’s just that I’ve become fascinated with painting the bigger mammals. Now, demand for both kinds of subjects is kind of pouring in.”

Spies describes his Duck Stamp illustration as “a super simple composition” in which he deliberately made sure he “wasn’t trying to do too much.” The crisp whiteness of the bird enabled him to accentuate contrast against the darker water. “Because of the size of the stamp, I wanted the image to rocket off the paper,” he says.

He explains an interesting anecdote about the decoy in his illustration. He found it, fully restored, it was too dark for the effect I wanted to convey, so I sanded it down and repainted it, he says. “I thought an old-school decoy would be much more visually stimulating than presenting a prop that appeared new.”

Since winning the Duck Stamp, Spies says he’s become more humbled after delving into the history of the competition. Of the 300 entries received this year he says at least 50 were “really something” and easily could have won.

Despite the doom and gloom in the market and uncertainty about the future of wildlife art, Spies is undeterred. He shares the details of a recent experience.

“The mother of a young girl who had entered the junior federal waterfowl competition came up and asked me what she thought her daughter should do, because it seemed not very worthwhile to be a wildlife artist,” Spies says. “I looked at her and offered a different point of view. I told her that I believed being a wildlife artist is a great thing. I’ve enjoyed getting involved in the business part, the marketing part and the best part, which is having a reason to get out there and explore.” I asked her, ‘How many other kinds of jobs give youth is kind of satisfaction?'”

Joshua Spies embraces his role as head cheerleader and genre ambassador, saying he hopes to be a mentor to younger kids. “There is an enormous amount of talent out there. I bet there are a thousand people my age who can paint better, but the one thing they won’t do is outwork me.

“It’s not easy being a wildlife artist,” he adds. “But I don’t think of it as really being competitive because everyone has their own style and 99 percent of us are rooting for each other,” he says. “The older artists have always been supportive of what I do and they all tell me the same thing: To get better you need to constantly paint and get out in the world to soak in things with your own eyes.”

Recently, as a sort of homage to his artist heroes, Spies enlisted 18 painters, including Brian Jarvi, John Banovich, Cynthie Fischer, Michael Sieve and Kobus Moller to render their own interpretations of a Marco Polo ram that Spies photographed in Tajikistan.

What can we expect from Joshua Spies in the future? Well, because he won the federal, he can’t submit another entry again for three years. “It’s a weird thing to accomplish something you’ve wanted for so long,” he says. “But I will be back. In my mind, I truly believe I can win it again.”

Meantime, he’s planning another series of trips to the belt of nations across southern Africa and becomes animated while describing his visit in northern Zimbabwe, which opened his eyes to world events and the impacts of political turmoil. And yet, once he left Harare and jumped on a bush plane, he felt as if he had gone back in time 200 years.

“We were in the middle of nowhere near the Zambezi River for 12 days. It was unbelievable,” he says.

A couple of times, they crept so close to Cape buffalo and elephant that he could hear them breathing. In this area not far from Mano Pools Preserve, there were lion, leopard, hippos and crocodiles. His former Rhodesian guides made sure he ventured into the thick of visceral wildness. While creeping toward a herd of buffalo in dense brush, they could hear lions roaring not far away and there were leopard tracks at his feet. Suddenly, the bush erupted with fleeing animals.

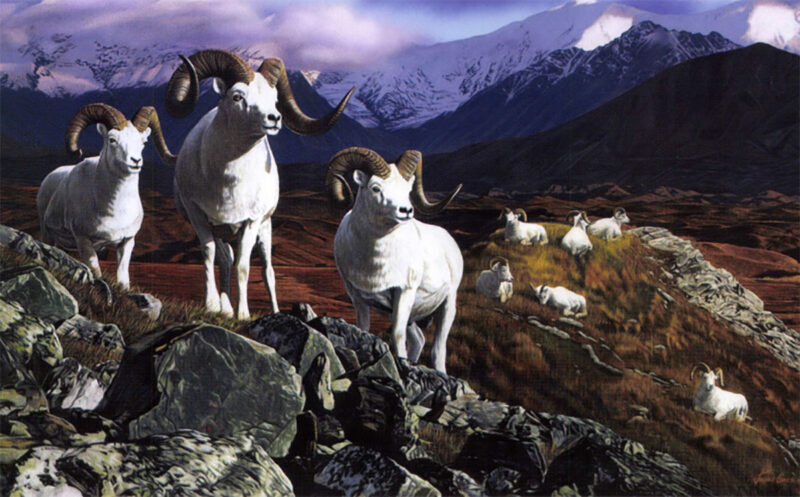

In Last Glance,

a herd of Dall’s sheep laze on a rocky mountain-top in Alaska .

“It sounded like a thunderstorm. Game running everywhere. Kind of freaky, actually. They know you’re there. They let you come close and then there is this chain reaction. After witnessing it, I’m moved to convey more of that unpredictability and sense of danger in my paintings.”

Spies is going to have a pair of reminders, for both he and his father took buffalo and he’ll use the heads as reference for future paintings.

“My wife is cool about having mounts in the house,” he says, admitting that with his living room walls now brimming with trophies and artifacts, they’re planning an addition. “I realize how fortunate I am that my career has allowed me to do these things, which is something, growing up here, I never expected,” he says.

“I love being able to paint the world, but you know something, Watertown isn’t such a bad place to be from.”

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now