His interests were narrow but deep—deep as the deep blue sea. Joshua Slocum was born to a sea-faring life in 1844, “on a cold spot on coldest North Mountain on a cold February 20,” back when ships were wood and men were iron. His granddaddy was an American Quaker, a pacifist who took up Canadian citizenship and a land grant rather than choose sides during the Revolution.

Five hundred acres near the Bay of Funday, swiftest currents and the world’s highest tides. West half of the province grew timber, east half grew rocks. Hard sometimes even to get a decent crop of potatoes. Life in Nova Scotia revolved around the sea. His father was not a fisherman, but he made boots for the fishing trade.

After a smattering of schooling, young Joshua went to work in the cobbler’s shop. His father, a rock-ribbed Baptist deacon, was a demanding boss and stern disciplinarian. Results were predictable. Joshua ran away at 14, took a job as a cook on a coastal schooner. At 16, he signed up as an Ordinary Seaman aboard a British merchant ship bound for Dublin, Ireland. From Dublin, Slocum traveled to Liverpool where he signed aboard another merchantman bound for China.

In the China trade, Slocum rounded Cape Horn twice, visited Jakarta, Manilla, Hong Kong, Saigon, Singapore and San Francisco. To ease the tedium at sea, he studied for the British Board of Trade exam. He passed, then earned second mate at 18 and first mate at 20. At 25, he was captain of an American freighter traveling between San Francisco and China, with stops in Alaska and Australia.

Over the next dozen years, he held command of eight ships.

Slocum married an American woman he met in Sidney and she joined him in his travels. The couple kept busy below deck, seven children in 13 years, all born in foreign ports.

Briefly stranded in the Philippines, Slocum organized local labor to build a 150-ton steamship. A steamship burned coal and coal cost money, but the wind was free. He took a schooner as payment, sailed it to San Francisco and thence back and forth between Alaska and Hawaii.

Slocum had another ambition—he wanted to write. He took a job documenting his travels as a temporary correspondent for the Sacramento Bee, the oldest newspaper in California.

When Slocum’s wife died of heart failure in Buenos Aires, he went home and took another, his cousin, half his age. But after sailing directly through a hurricane, surviving a pirate attack, a mutiny, cholera, small pox and shipwreck, his new wife lost all enthusiasm for the seafaring life.

Slocum built a 30-footer from timbers salvaged from the wreck—“an ocean-going canoe.” He loaded up his wife and kids and sailed it 5,300 miles to Cape Romain, South Carolina, sending his recently and suddenly estranged wife and the youngest kids home by train to her family in Nova Scotia.

But the world was catching up to Captain Slocum; steamships were replacing the beautiful and graceful old schooners and square-riggers. The age of wooden ships and iron men was slowly but relentlessly becoming the age of iron ships and wooden men.

Not much call for sailing sea captains anymore. In the winter of 1893, down to his last dollar and his marriage on the rocks, Captain Slocum was in Boston visiting an old whaling captain, a man like Slocum, whose skills were no longer needed by a changing world.

“You want a ship?” the old salt inquired. “I’ll give you a ship!”

The ship was Spray, a century-old, gaff-rigged oyster sloop, 36 feet, 9 inches, abandoned in a pasture with a tree growing up through her. “She’s in want of some repair,” the whaler cautioned. But Spray had “good lines,” a vague but absolute assessment by those who go down to the sea in ships, or boats, in this case.

But before Slocum got a chance to work on the sloop, he embarked on his “hardest voyage without exception,” to deliver a motor torpedo boat to the Brazilian navy.

The Destroyer was a 130-footer designed by the famed Swedish-American naval architect John Ericsson, inventor of the screw propeller and builder of the Union warship Monitor. The Brazilians were in the midst of a political discussion—an armed standoff—half the navy on one side, the other half on the other. Rebels were threatening to bombard Rio de Janeiro, and Slocum was promised “a handsome sum in gold” if he got Destroyer there in time.

But Slocum had ulterior motives. The leader of the rebels, one Admiral Custodio Jose de Melo, had treated Slocum unkindly during his last voyage to those parts, and Slocum burned to get even. He planned not only to deliver the ship, but to take it into action against Melo’s flagship.

“I was burning to let him know and palpably feel that this time I had dynamite instead of hay.” But it was 3,600-odd miles to Melo, and then the torpedo had to be delivered to its target from only 300 feet.

If any man could have done it, Joshua Slocum could have. But alas, no man could.

While Ericsson’s Monitor fought the rebels to a standstill in the first duel between ironclads, it sunk in a gale off Hatteras a few months later. Destroyer was equally unseaworthy. She popped rivets and split seams in heavy seas. The crew bailed for their lives. Seawater put out the boiler, and Slocum got it relit by feeding it busted up furniture and pork lard from the galley. It took a month to reach the Caribbean where the weather improved enough for repairs and refitting.

On January 20, 1894, after finally meeting up with the loyalist fleet, Slocum thought it wise to test-fire the torpedo before confronting Admiral Melo. But wet powder resulted in a misfire. The torpedo stuck in the tube, and the only way to remove it was to beach the boat and winch the fully armed projectile out by hand. This put additional strain on the hull, popped more rivets and opened more seams. Frustrated Brazilians seized the ship and put a new crew aboard, which promptly ran it onto a reef. Destroyer was abandoned and Slocum never got paid.

Back in the U.S., Slocum went to work on Spray, cutting a white oak growing nearby and replacing bow-spit and keel. Replacement planks were rot-resistant Georgia heart pine. Slocum had a steady parade of visitors and plenty of advice.

“She’s a fine craft indeed, Captain, but can you make her pay?”

Slocum would make her pay. No, he would not use Spray to harvest oysters. He would sail her solo around the world and write a best-selling book about the adventure. He kept that to himself, for a while at least.

It took a year and $553.62, a fair chunk of change in those days when a good man was happy with a dollar a day. And then Slocum took her across the Atlantic in four weeks.

There were some pleasant surprises. He caught cod and halibut, feasted on sea turtle. Breakfast was flying fish that came aboard overnight. Porpoises followed him like dogs and came to the sound of his voice. A passing ship sent over a bottle of very good wine. By this time, papers were a-buzz with news of his voyage and the captain of a Spanish ship offered up prayers.

“He was a good man . . . for a Spaniard,” Slocum wryly noted.

But the biggest surprise was Spray, herself. Most sloops have a “weather helm,” a mildly annoying tendency to turn into the wind, much better than the alternative, a “lee helm,” when the sheet gets a wind behind the luff and the boom rockets across the deck, sweeping the unwary overboard. But the Spray was so perfectly balanced she would sail herself. Slocum could lash the wheel and go to bed, and the boat held her course all night long.

Slocum navigated by “dead reckoning,” by which you were dead if you reckoned wrong, a joke among seafarers to this day.

But it was no joke back then. Spray towed a “log,” a little torpedo with a propeller that recorded nautical miles. Run a course by the compass, factor in the miles and you could find your vague position on the chart. Final lock was latitude and longitude, certain degrees at certain times of certain stars above the horizon, the height of the sun above the horizon at exact noon. This required a highly accurate clock—a chronometer.

Slocum’s chronometer was in bad repair and cleaning and calibrating would have cost 15 whole dollars. Once Slocum laid aboard his rations, he did not have 15 dollars, so he bought a cheap tin clock for a dollar. He verified his position by hailing passing ships. His cheap tin clock was always spot-on.

At Gibraltar, the Brits treated Captain Slocum like visiting royalty. A British Navy steam launch towed Spray to the government dock. He got a guided tour of secret gun emplacements carved into solid rock. The governor and Her Ladyship took him on a sumptuous picnic on the Moroccan seashore.

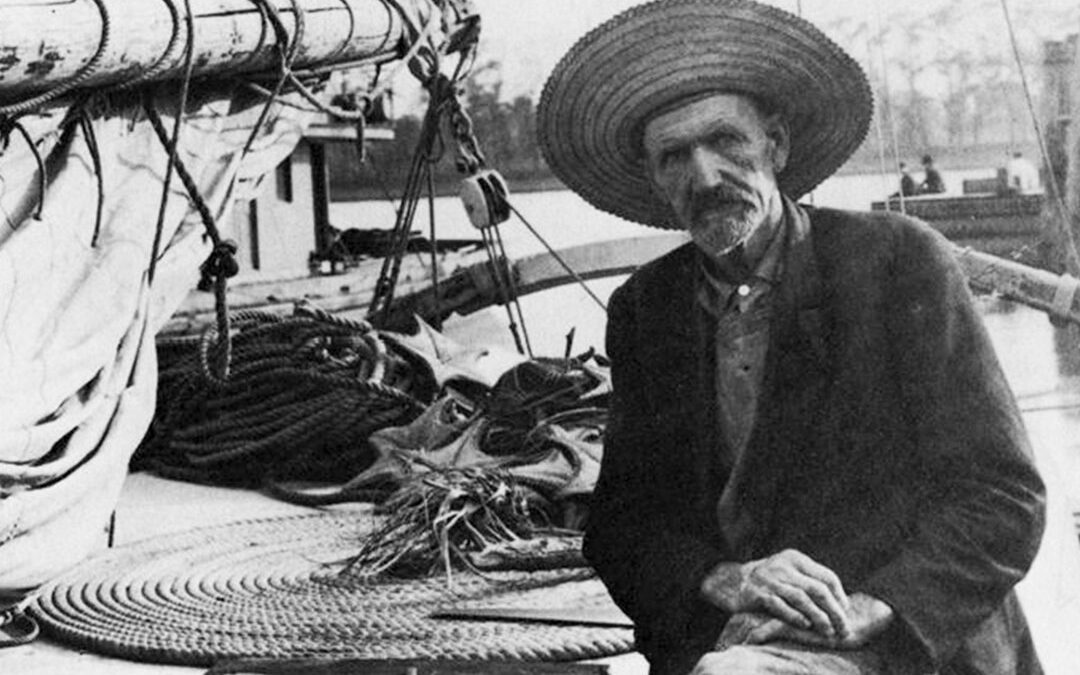

Joshua Slocum checks out the Moroccan shore where he would be treated to a picnic by the governor.

But there was bad news. Slocum’s planned route, across the Mediterranean and through the Suez Canal into the Red Sea and thence to the Indian Ocean, was rife with pirates. A lone navigator had little chance of surviving that passage.

So Captain Slocum just traveled 3,440 miles solo in the wrong direction? No problem. He’d bump along the Moroccan coast, ride the trade winds to Brazil, a place he still held in great affection despite his shipwreck and misadventures aboard Destroyer. But backtracking to avoid pirates, he ran smack into them anyway, a crew of swarthy Moors who gave chase in a lateen-rigged Arab felucca—a damn fast boat. The wind and seas were rising when Slocum ran up as much sail as he dared. Spray was fast but not that fast, and Slocum figured he had about three hours to live.

They shot at him, close enough now to see “the tufts of hair on the heads of the crew—of which it is said—“Mohammed will pull the villains up into heaven and they were coming on like the wind.”

Just when Slocum thought things could get no worse, they did—with a mighty crack, the mainsail boom snapped off at the mast. Slocum went below, broke out his rifle, a single-shot black-powder Martini Henry, but when he came back on deck, there was nothing to shoot at. The same gust that had broken his boom had also totally dismasted the felucca. She was far astern and the pirates were struggling to retrieve their rigging from the sea: “may Allah blacken their faces.”

Finally, on the Brazilian coast, Slocum learned Admiral Melo was now military dictator of the country. When he asked a customs officer about the money due for delivering Destroyer, the Brazilian knew it was anticipated by the losing side and replied, “Oh Senor, we remember you well! We have been saving it for you. You may have it back any time you wish.”

The torpedo boat was still on the reef, its smokestack showing at low tide.

Adventure upon adventure. Grounded in Uruguay, feted in Buenos Aires, Slocum cut seven feet off Spray’s mast, five feet off her bow-spit, shortened the sail as he well knew the roaring hell to come.

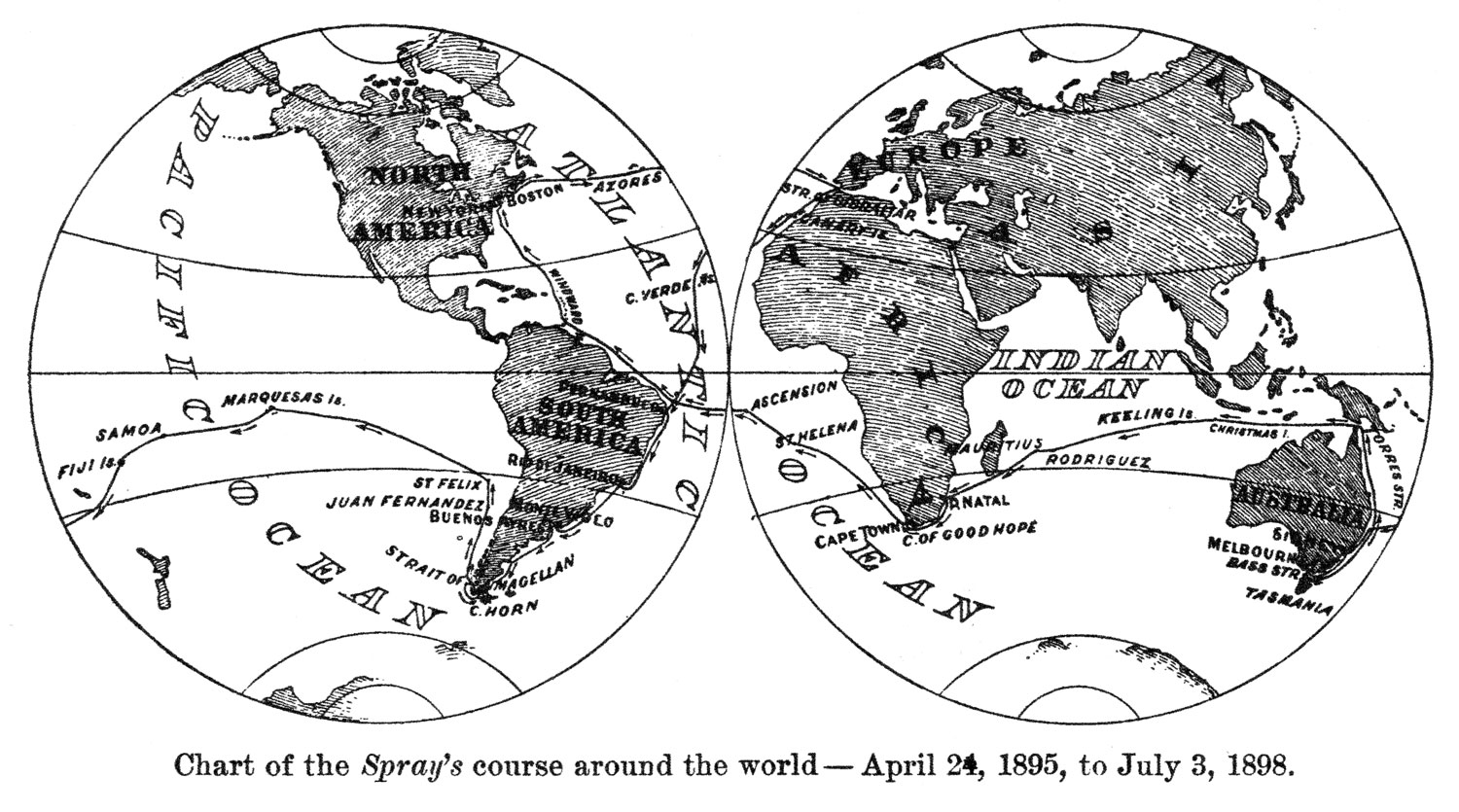

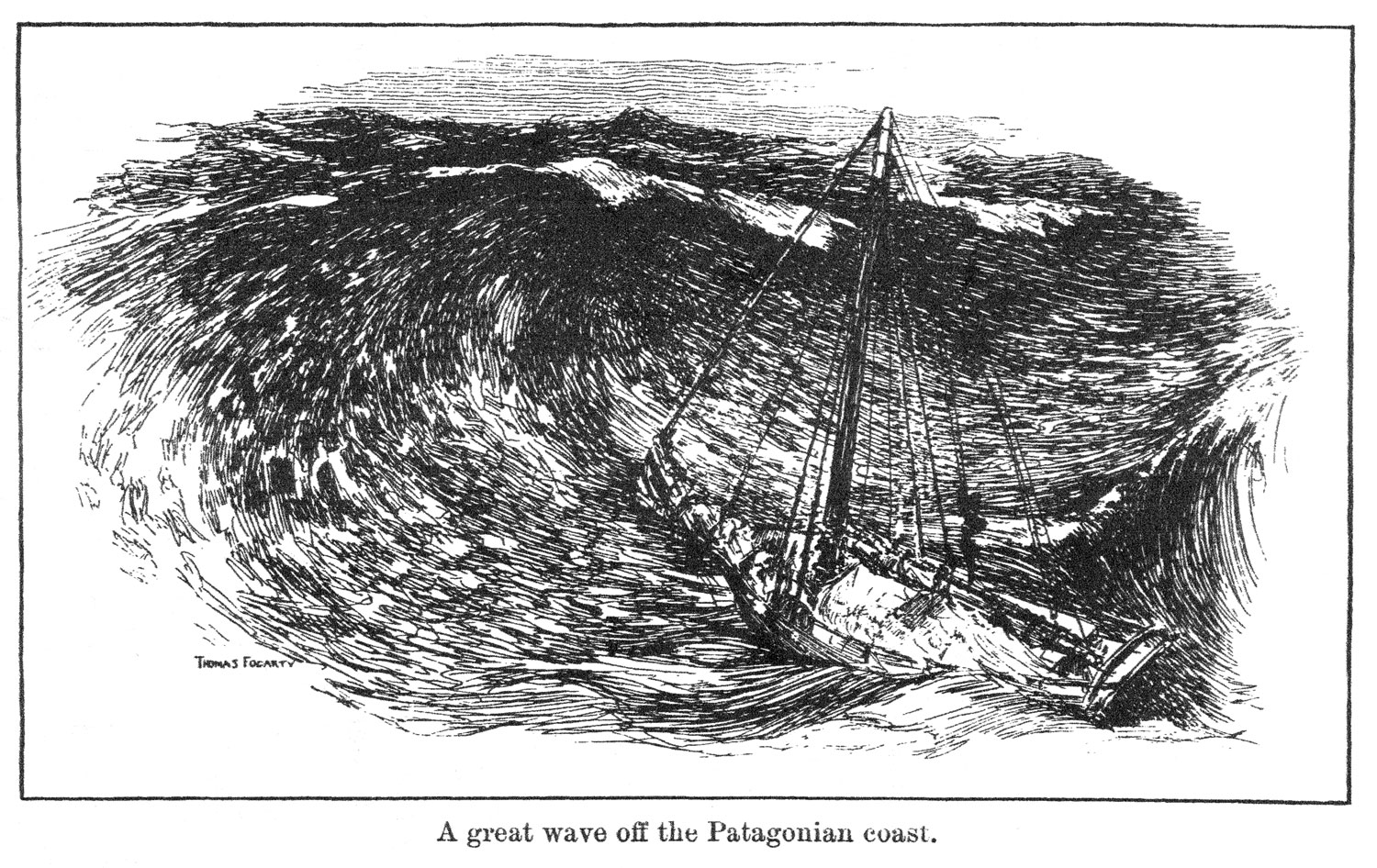

Spray entered the Straits of Magellan on Feb 11, 1896. With a 20-foot tide on the Atlantic side, only a four-foot on the Pacific, the Straits ran like a millrace with winds howling down the Andes. It was 350 miles of some of the most treacherous water on earth—outside of the alternative route, Cape Horn itself.

At a Chilean coaling station halfway through, he was again warned of pirates and given a bag of carpet tacks with the advice to spread them on the deck each night because the pirates were generally barefoot. Slocum made scarecrows—or rather scare-pirates—of extra clothes so he did not appear to be alone. He was approached during daylight and drove them away with gunfire. When the pirates attempted a night attack, they ran into the carpet tacks and “howling like a pack of hounds,” leapt into the sea. Slocum gathered up the tacks not implanted in pirate feet and saved them for his next anchorage.

He cleared the straits on March 3 and entered the Pacific Ocean, so named by Balboa when he saw it on a rare calm day in 1519. But a roaring gale shredded Slocum’s sails and blew him right back to where he’d been. He hand-stitched the damage with needle and thread, then made a note to himself in his journal: “Next time use a bigger boat.”

He didn’t get back onto the Pacific until April 11, but by mid-July, he was in American Samoa, enjoying supper with Mrs. Stevenson, the widow of the author of Treasure Island.

He was reported lost as sea several times and major newspapers ran his obituary, but like Mark Twain, reports of his death were greatly exaggerated.

By October 10, Slocum was in Sydney, Australia, where he received a gift of new sails. His old sheets, patched time and time again, resembled “Joseph’s coat of many colors.” By December 29, he was in Cape Town and took a train up to Pretoria, where he met and debated Paul Kruger, the president of the Boer Republic who steadfastly maintained the world was flat because the Bible mentions vier hoeke van die aarde, “the four corners of the earth,” and a sphere has no corners.

On May 8, 1898, Slocum was once again off the coast of Brazil, having completed his circumnavigation of the world in 36 months, 14 days, the first man to do it alone.

Slocum was a hero. They hauled his sloop up the Erie Canal for the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo. He went on a lecture tour. He sold snips of sail. He spoke at a dinner honoring Mark Twain. He dined at the White House and visited Teddy Roosevelt at his summer home. He took the president’s son sailing.

Living aboard Spray at anchor, Slocum massaged his journals into a book, published in 1901. Sailing Around the World Alone is a ripping good yarn—fast, fraught with danger and funny as hell. It was an international bestseller and remains in print to this day.

Slocum bought a farm with the proceeds and tried to give up the sea. But the Captain was not meant to follow the plow. He was lost at sea somewhere in the southern Bahamas on or about November 6, 1906, likely run down by a steam mail packet.

The man who circumnavigated the world alone could not swim. The man who was rendered a relic by steam ships was finally killed by one. Ten years later, a court found him legally dead.

End of story?

Not quite.

There is a Joshua Slocum Society founded in 1953 dedicated to keeping his memory alive and “to record, encourage and support long-distance passages in small boats.” There is feature documentary online. Spray is widely replicated, reputed to be the single-most replicated boat in the world, and lovingly sailed. Spray cost Slocum $553.62. Your’s will start at about a hundred grand.

And then there are three of his great-great granddaughters, blonde and beautiful, who still follow the sea. Tracy Slocum markets waterproof and windproof blankets for recreational boaters under the trade name Pretty Rugged Gear out of Albany, New York, with a dozen other products under development. Photos of her great-great grandfather and Spray are all over her website.

And then the twins: Justine and Crystal. They have Florida surrounded—Justine on the East coast, Crystal on the West. They call Justine “Skipper.” She lived for years on a sailboat somebody gave her. She named it Spray. She’s been to sea school, bummed the Bahamas, served as third mate aboard a recreational fishing vessel, Super Critter out of Ponce Inlet, targeting whatever’s biting for the tourist trade. She’s fixing to leave for a gig on a long-liner working the Gulf of Mexico, 15 days at sea, 15 days off. Good money, she says.

Crystal lives on a boat at Madeira Beach. She volunteers in underwater archeological education, shipwrecks and maybe lost treasure.

“My father was an only child, my grandfather was too,” she says. “I got the Joshua genes pretty hard.”

What does she do for work? “I don’t, but whenever I have need of currency, I sell bait.”

Crystal has “Saltwater Hippie” tattooed on the side of one foot, an anchor on each heel.

Joshua would have been mighty proud of all of them.

Salt is strong and blood runs deep, deep as the deep blue sea.