As both sportsman and art lover, my walls battle for either mounted heads or country scenes. Oddly, though, I own no wildlife art. Before visiting John Schoenherr I wasn’t sure why.

Now I am. Over the years, most wildlife has seemed partisan to me, as though the artist sought to humanize his subject — the dams and young are too soulful and compassionate, the predators too cunning, the big five too arrogant — as if making animals more like men would make them more noble. (It makes them less so.) As commercially gratifying as this has been for artists such as Audubon, it is, nonetheless, contrived. To be taken seriously, especially by sportsmen who live in and create their own fashion of art, a work must be true.

Now I am. Over the years, most wildlife has seemed partisan to me, as though the artist sought to humanize his subject — the dams and young are too soulful and compassionate, the predators too cunning, the big five too arrogant — as if making animals more like men would make them more noble. (It makes them less so.) As commercially gratifying as this has been for artists such as Audubon, it is, nonetheless, contrived. To be taken seriously, especially by sportsmen who live in and create their own fashion of art, a work must be true.

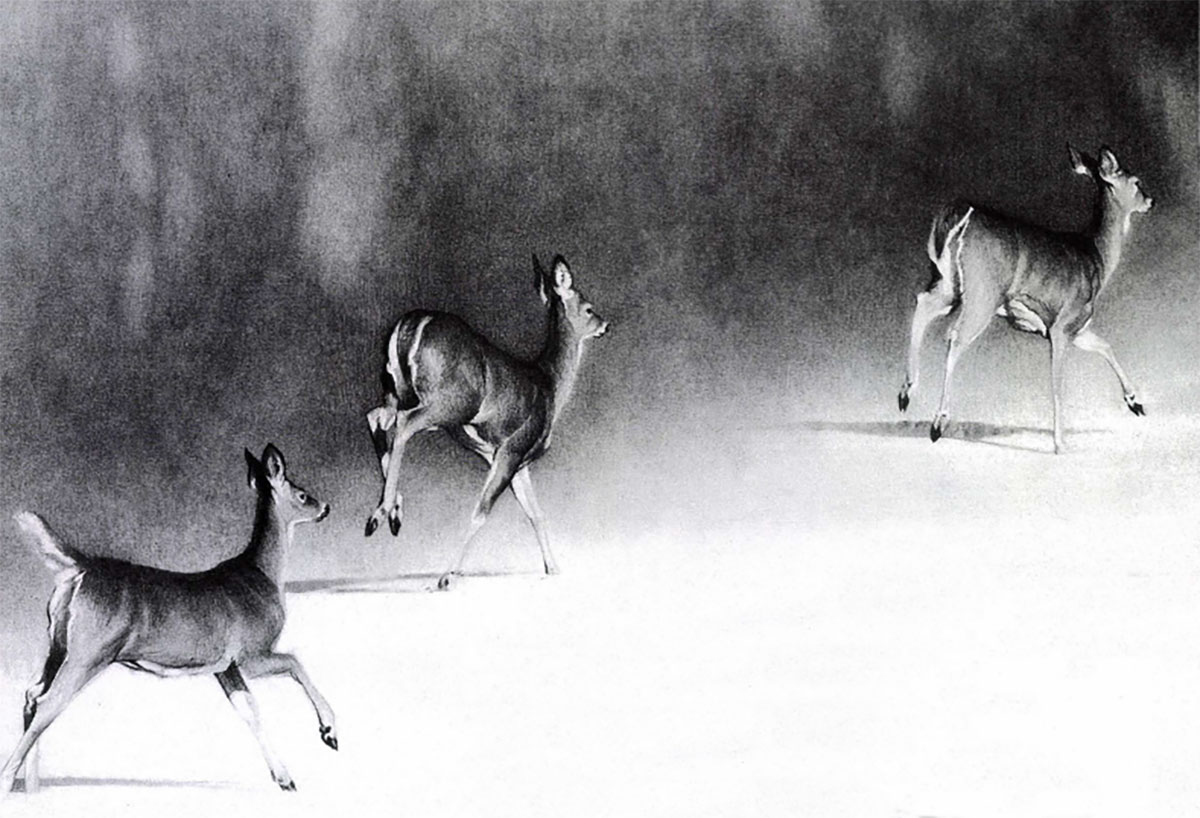

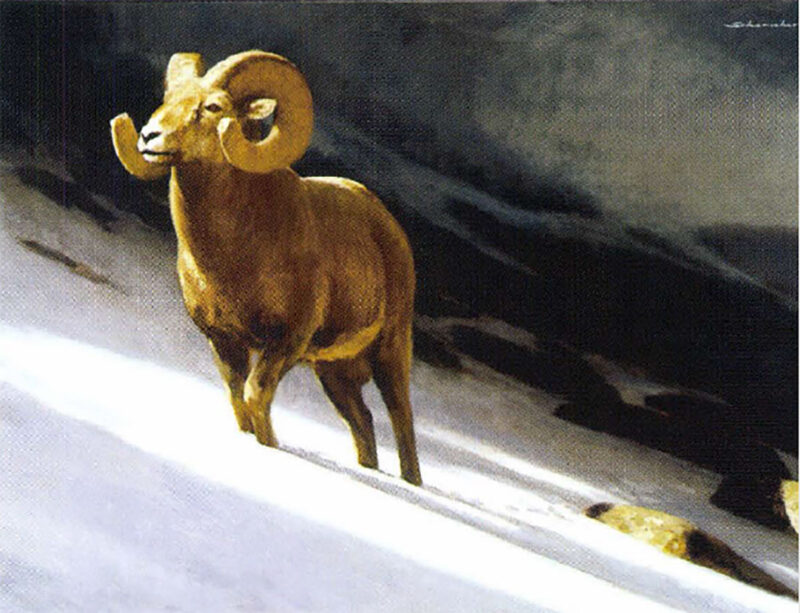

John Schoenherr paints truly and without sentiment, like someone who has known many animals. If his subjects appear expressionless, it is because a grizzly, for example, lacks the necessary emotion to produce a human look. A grizzly is no less animate for it and would appear so only to those unfamiliar with wildlife. Schoenherr’s genuineness can change the way you feel about both art and nature. You gaze at the subjects of his paintings – elk, cougar, bighorn -and realize you are looking into the face of every wild creature you have ever seen.

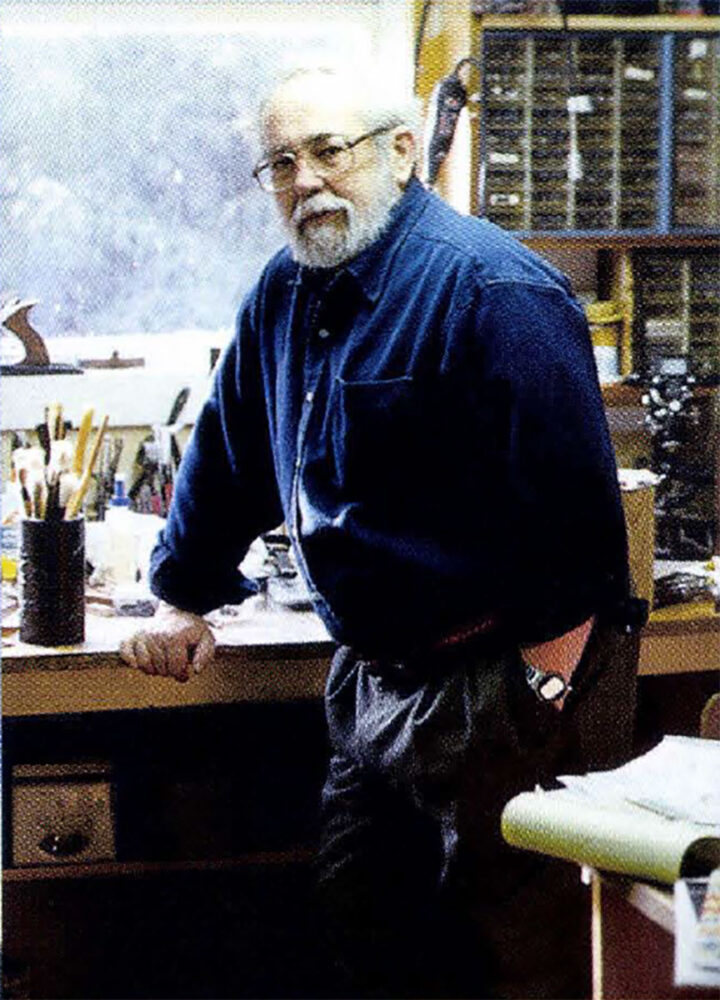

I visited him recently at his rustic home in Stockton, New Jersey. He greeted me, and we toured his 19th century farmhouse decorated with collectibles from his early years. Later, he led me perhaps thirty yards behind the house to his studio, which sits slightly uphill When not in Alaska or the American West in search of subjects, it is in this converted barn that the artist has spent the last 25 years, often working on six or seven paintings at once.

“Most of my paintings start as visions,” John explains. Beginning from memory or a photo taken while camped in Denali or Katmai Parks, he then sketches “a little thumbnail of what I might try to do.”

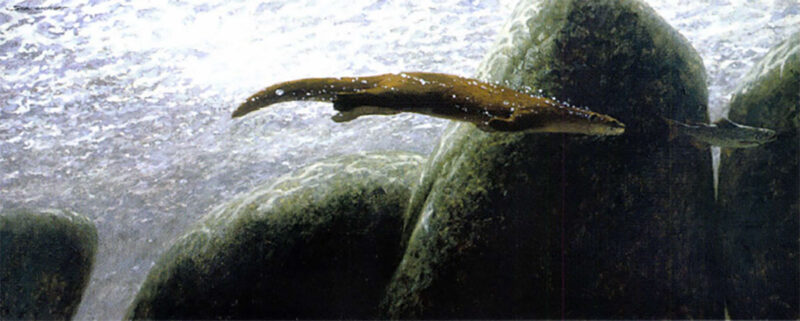

I saw such a thumbnail and the nearly completed result: a two- by five-foot underwater scene of an otter chasing a brook trout. Inspired by summer visits to The Adirondack’s Opalescent River as a boy, John’s success in this painting goes beyond predator and prey. At the top of the canvas, the river surface doesn’t rush, but moves deliberately Deeper and darker, the same current flows by submerged rocks that stand like the ruin s of a former civilization. He has captured the otter as it levels off in sleek pursuit of the trout. Altogether, it is a compelling scene, the kind that tantalizes your eye and triggers your imagination.

Born in Depression-era New York in1935, John Schoenherr wandered the abandoned lots and not-yet-developed fields of Queens, observing trees, birds and other small animals. He sketched for fun and to entertain boyhood friends who spoke less English than he did. “Those kids were Italian, Irish and Chinese. Until we all learned English, I communicated with them through my drawings,” he remembers. “The big moment came when my father took me on one of those old Circle Line cruises up the Hudson to Bear Mountain.” It was on that voyage that John began his lifelong fascination with bears. Though he paints many different animals, bears — particularly Alaskan coastal browns — are his primary focus.

Born in Depression-era New York in1935, John Schoenherr wandered the abandoned lots and not-yet-developed fields of Queens, observing trees, birds and other small animals. He sketched for fun and to entertain boyhood friends who spoke less English than he did. “Those kids were Italian, Irish and Chinese. Until we all learned English, I communicated with them through my drawings,” he remembers. “The big moment came when my father took me on one of those old Circle Line cruises up the Hudson to Bear Mountain.” It was on that voyage that John began his lifelong fascination with bears. Though he paints many different animals, bears — particularly Alaskan coastal browns — are his primary focus.

One of my favorites, Skyscrapers, is a panoramic study of an unusually large brown on a solitary gravel island. Approaching fair sky undermines the general gloominess of a passing afternoon rainstorm, conditions common to late-summer Alaska. The bear is up on its hind legs, with his head turned into the wind and clearing weather. At that height, the new sunlight falls on the bear’s face and chest as it does on along stretch of spruce on the far shore. In the distance lies the base of Mt. McKinley, still enshrouded by rain clouds.

It was at Stuyvesant High School that the young Schoenherr decided to pursue art as a career. “I preferred drawing frogs to dissecting them.” He went on to earn his Bachelor of Fine Arts at Pratt Institute. After a brief stint in an art studio, he set out to become a freelance illustrator. His initial projects were in science fiction magazines and the covers of paperback books.

Schoenherr’s fame as a children’s book illustrator began in 1963 with Sterling North’s now famous Rascal. Since then, he has illustrated nearly 50 others, including the classics Gentle Ben, Julie of the Wolves and Owl Moon, which earned him the 1988 Caldecott Medal, the field’s highest honor. He is also remembered for his cover illustrations for the highly successful Dune sci-fi series, which later became a movie.

Next to bears, geese are a major Schoenherr subject. In 1994, his exquisite rendering of two Canada geese on a misty morning pond, entitled Early Risers, won a special Award at the Hiram Blauvelt Museum in New Jersey. Canadienne, which earned a medal from The Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences, is a tonal understatement of a wild goose at twilight. Like his other work, it is masterfully subtle. Painted 14 years ago, it now hangs in The Choenherr living room. While I was looking at it, John offered to turn on the lights. I asked him not to, as the scant afternoon light form the windows made the image seem all the more elusive.

Another, Catwalk, depicts the almost surreal figure of a cougar traversing the shadows beneath a rock overhang. It is among the better examples of how John’s subjects pick up the surrounding colors to become part of the landscape.

Another, Catwalk, depicts the almost surreal figure of a cougar traversing the shadows beneath a rock overhang. It is among the better examples of how John’s subjects pick up the surrounding colors to become part of the landscape.

I asked the prolific artist about sustenance, about fuel.

“Some years ago, Doug Allen (a friend and fellow artist) and I were complaining about the lack of inspiration. Our wives told us to shut up and go west. That’s what we did. We wandered around for three weeks and ended up in South Dakota looking for buffalo. We drove over a slight hill and wound up in the middle of a herd. All were bigger than the car.”

On another of many trips to Alaska, he sat photographing the mountains. Suddenly a brown bear of about 700 pounds appeared in his viewfinder. John sat perfectly still while the bruin passed him — at a distance of six feet.

Such hairy encounters go with the terrain. It is clear that John would not compromise his work by being too conservative. He and Allen are discussing a trip to southern Africa in 1999 and the wealth of inspiration to be found there.

Tom Carson, owner of The Carson Gallery in Denver, is Schoenherr’s principal dealer, having represented him for 24 years. Says Carson, “John is not trying to pussy-foot around. His paintings are bold, his images are strong. They appeal to a very strong individual. Other artists often remark that they wish they had the confidence to present their subjects like John.”

As a result, Schoenherr’s art has enabled Carson to develop a most unusual profile of customers, many of them top executives, Fortune 500 CEOs, entrepreneurs and other high-flying achievers at the top of their own food chain who pay anywhere from $10,000 to $20,000 for a painting. I was somewhat surprised to learn that John’s work remains largely undiscovered by Safari Club members and other dedicated big game hunters I personally know many sportsmen who will not be able to live without his work once they see it.

In his element, the studio, lay the accoutrements of John Schoenherr’s craft. He ambles by jarred rows of upturned brushes like a bear in waist-high grass.”

In his element, the studio, lay the accoutrements of John Schoenherr’s craft. He ambles by jarred rows of upturned brushes like a bear in waist-high grass.”

A friend once told me that I am actually a bear disguised as a man,” he growls. “Furry, grumpy, solitary.”

A self-described existentialist, he is the artist’s artist, unconcerned with the trivial, loathsome of distraction.

“I’m trying to make some sense of my art,” he says with a not too frequent grin. “I find a lot of art today is one-shot. You see it and say ‘Oh, yeah, wow’. You walk away and five minutes later it’s out of your mind. I want to do things that people keep wanting to look at.”

“I’m trying to make some sense of my art,” he says with a not too frequent grin. “I find a lot of art today is one-shot. You see it and say ‘Oh, yeah, wow’. You walk away and five minutes later it’s out of your mind. I want to do things that people keep wanting to look at.”

And one does, beyond simple admiration for this artist’s major talent. There is the urge to step inside John Schoenherr’s paintings and explore the terrain, to search beyond the limits of the canvas for something else — one’s self perhaps.

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now