If John Bryan was looking for the easy way out, he never would have tried to make it as a sporting artist in wood.

But then again, this is a guy whose favorite quarry is the ruffed grouse, whose idea of fun and games is slashing through thickets of alder and oak in search of a few good shots. The rougher the cover the better, not because he thinks there’s something particularly macho about wrestling with briar bushes the size of pickup trucks, but because he knows that’s where he’ll find birds.

Cruising Tarpon – Wall Panel in White Pine.

Bryan’s been that way for a while. Unlike most of his classmates at Choate School in Wallingford, Connecticut, for example, he didn’t head right off to college after graduating in 1973. Instead, he took a job as a lumberjack with the Great Northern Paper Co., working for a year along the Maine-Canadian border before trading in his chainsaws for textbooks and starting classes at the University of New Hampshire. He spent four years there, but rather than joining his peers on Wall Street and Madison Avenue when his studies were done, Bryan returned to open his own furniture business. “I knew it would be a tough way to make a living,” he says, “but it was something I really wanted to do.”

But soon even that became too mainstream, and Bryan felt a certain dissatisfaction with his work. So not long after building a post-and-beam home on seven acres of woodland in North Yarmouth, Maine, not long after his wife Winty had given birth to their third child, he decided to forsake furniture-making altogether and carve fireplace mantels and wood panels.

First Beat – Grouse in Walnut

“It seemed completely nuts at the time, considering the debt I had accumulated and the new baby,” Bryan says. “But I was getting stagnant. I needed to do something that would let me inject more of my personality into my work, that would help distinguish it from others.”

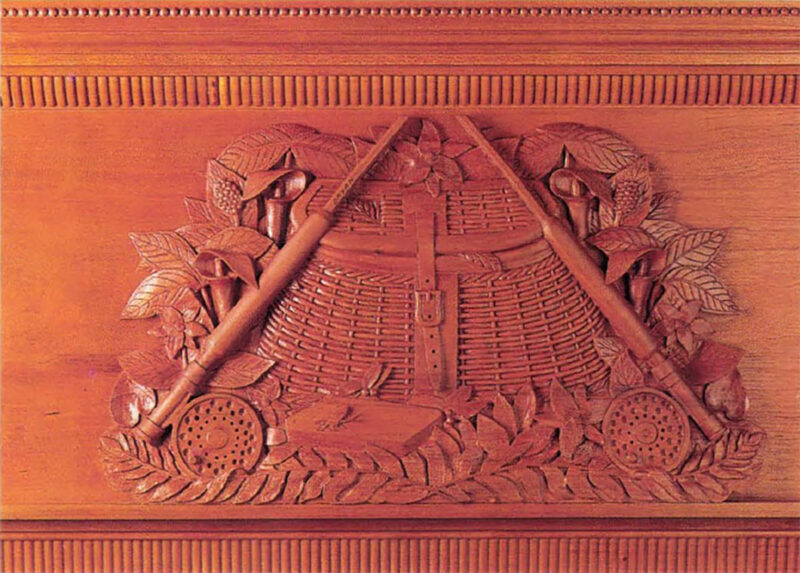

He made that move five years ago, and in that time Bryan has created some of the most dramatic and distinctive pieces of sporting art in the country. From an intricate cherry fireplace mantel with hand-carved trout flies to a basswood panel featuring a woodcock spiraling through sumac branches, he has fashioned unique, extraordinarily beautiful works that evoke the genuine spirit and grace of hunting, fishing and the outdoors.

Bryan works out of an airy, two-story barn he built a couple of hundred yards from his home. There, with his wood stove burning, his Labrador retrievers —Emmy and Tiller — curled up on dog beds, his stereo cranking out tunes from the Allman Brothers Band Live at the Fillmore East album, he hunches over a slab of black walnut and chisels out the image of a grouse in flight. His six-year-old daughter Skyler ambles in after school, hops on a bike and begins pedaling between the planers and saws set up around the barn floor. Neatly arranged in one corner of the shop are some of Bryan’s most recent works: a pine mantel featuring a pair of Atlantic salmon hovering over a gravel riverbed; a cherry panel with two swimming loons; a walnut sculpture of an osprey perched on a tree branch with a weak fish in his talons.

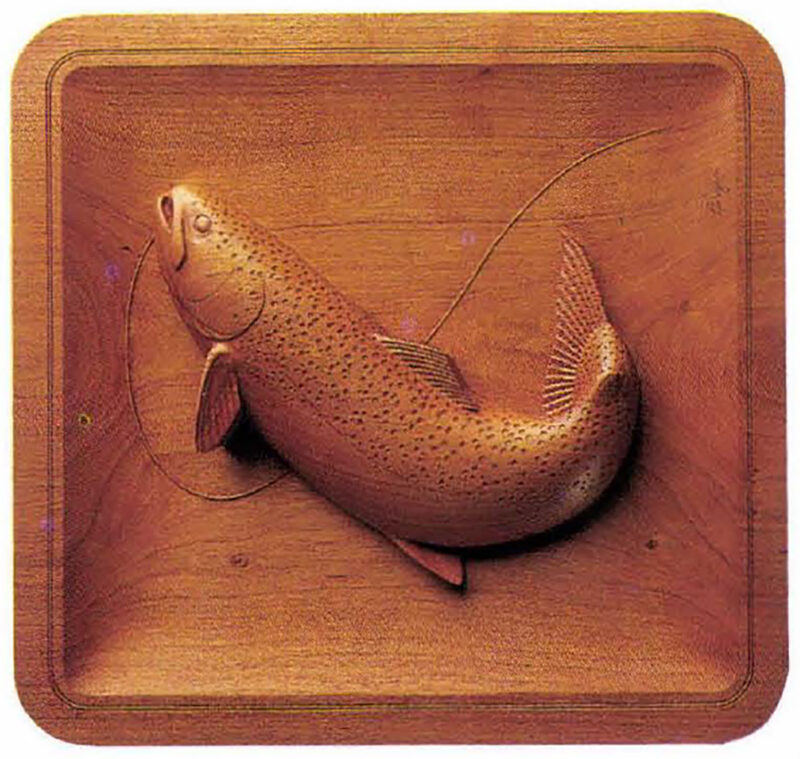

Talented Maine carver John Bryan fashioned Permit Schooling from a 24x 36-inch piece of basswood.

“I sort of got into this by accident,” he says between cuts. “I took lots of side jobs when I was making furniture, re-canvassing old canoes, making signs for guided missile frigates the Navy built at Bath Iron Works nearby— anything to help make ends meet. Once a woman asked me to carve a fireplace mantel, something in the Adams style, with flowers, acorns and sheaves of wheat. It was a major learning process, because I was exploring new territory But I really enjoyed doing it, and I liked my client’s reaction.”

Soon after Bryan completed the mantel, an acquaintance began talking to him about the country house she and her husband, a sporting art collector and wingshooting enthusiast, were restoring. “Do you think you could carve a mantel with an upland hunting scene?” she asked. Bryan nearly fell over. “Here, finally, was a job that would allow me to combine my love of the outdoors with my skills as a woodcarver. I thought I had died and gone to heaven.”

Nightstalkers – Striped Bass in Walnut.

Bryan has made that trip several times since then, usually with very satisfying results. “My primary goal is to elevate people’s expectations of what they can see in a piece of wood. The medium has a lot of soulfulness, and I try and bring that out in each piece.”

About 40 percent of his work is done on speculation; the rest is commissioned. The first thing Bryan does with a prospective client is talk extensively about the project.” Some people have a very specific request,” he says, “and already have a certain motif or theme in mind. Others are not so sure, so it’s up to me to help them create something special. I’ll go to their house and walk around their grounds, see what their interests are, their surroundings, see what’s important in their daily lives, get to know them a little bit. And we’ll go on from there.”

Once the basic idea is agreed upon, Bryan composes a pencil drawing, which he then reviews with his client. “That gives him, or her, a chance to react and editorialize. If we sit down together and plan accordingly, there’s no reason why we can’t create something of tremendous quality.”

Once the basic idea is agreed upon, Bryan composes a pencil drawing, which he then reviews with his client. “That gives him, or her, a chance to react and editorialize. If we sit down together and plan accordingly, there’s no reason why we can’t create something of tremendous quality.”

After the final design has been approved, Bryan heads for the sawmills in search of the appropriate piece (or pieces) of wood. He buys the wood rough and mills it himself in his shop. Then, working primarily with hand chisels, he carves the image.

“How long I spend on each piece depends, of course, on the piece itself;’ he says as he gets up from his stool and walks over to the salmon mantel. “I did this on spec, and it took about 350 hours. I’m asking $14,000.” The panels, which are smaller and can be hung like paintings, take anywhere from fifty hours on up and start at $2,500.

So what is it that doesn’t come easy? “Money, for one thing,” Bryan says. “Coming up with enough work is another. I know I have the talent, but this is still a very difficult way to making a living, especially with an uncertain economy and a family of five to feed and clothe.

So what is it that doesn’t come easy? “Money, for one thing,” Bryan says. “Coming up with enough work is another. I know I have the talent, but this is still a very difficult way to making a living, especially with an uncertain economy and a family of five to feed and clothe.

“Woodcarving is a challenging profession;’ he adds.” I want to impress people with my seriousness, and I’m driven to attempt things I haven’t ever seen before, to make my work that much better. I take a lot of risks, and coming down the home stretch on a mantel or panel is like walking on coals. There’s a certain element in each of my pieces — be it a trout fly or a fishing line or a sumac branch — so delicate yet so central to the feel of the carving that if I mess it up in any way, I ruin everything. It’s tough because I put a tremendous amount of heart and focus into my work, and when I’m done with a piece, I feel completely drained, like I’ve been emotionally mugged. Sometimes it’s very hard going back out to the shop the next day and starting all over.”

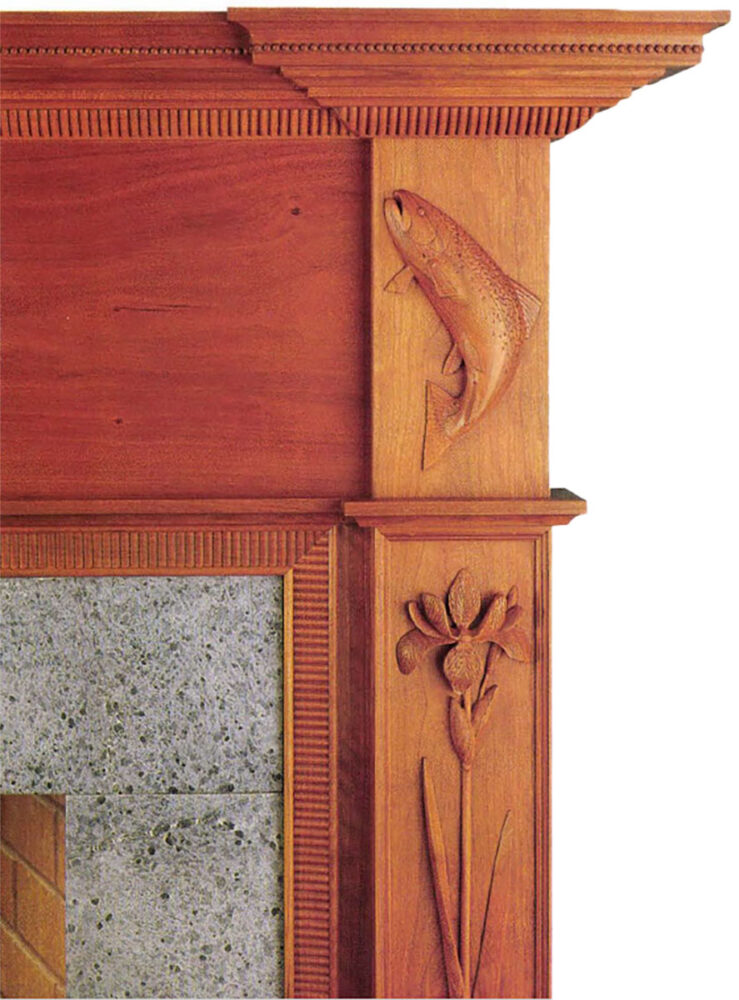

Landlocks – Hearth Panel in Cherry

The profession can also put some strain on a marriage, especially when the days between commission checks begin to add up and the Bryan clan keeps on having to do without. “I was out buying some wood for a job a couple of years ago;’ Bryan recalls, “and I found this gnarly walnut stump, so big it didn’t fit in the back of this guy’s pickup truck. It was an ugly tangle of roots, but I saw potential in it, so much so that I bought it off the guy for $150. My wife wanted to kill me when I showed up at home with a stump in the back of an old pulp truck, especially after telling her what I paid for it. I was in the middle of pretty bad dry spell, and there were so many other things we could have spent the money on. But over the next six months I carved and then sold two sculptures from that stump and have three others in the works. So I think she’s forgiven me.”

The artist devoted almost 350 hours to creating Streamside, this beautiful fireplace mantel with its intricately carved figures. Bryan prefers cherry for a large piece such as this. “It’s readily available in high quality, yields good detail, and the wood ages to the kind of really nice patina that many people are looking for,” he explains.

Tough as it may be at times, Bryan’s work has its obvious rewards. One is the money that comes with each sale. And there are a number of non-cash payoffs. “I get a real thrill finding someone who wants to buy something that has come from my heart and soul,” Bryan says. “I also like the creative process, coming up with different ideas, being able to give a fish or bird a certain attitude or personality just by carving their eyes a particular way. It’s exciting to complete a job that not only stretches my creative boundaries, but also thrills the client. But the best part of all is the finishing — putting the oil on a piece of wood I’ve worked with so long, rubbing it in and letting the color and grain come alive.”

Bryan walks back to his stool and resumes shaving pieces of walnut from his carving. He certainly didn’t take the easy way out when he picked this line of work. Yet, through sheer talent and determination he has literally carved himself a place among the sporting art elite. But if you know him at all, you realize that isn’t such a remarkable feat. For this is a guy who doesn’t miss many grouse shots either.

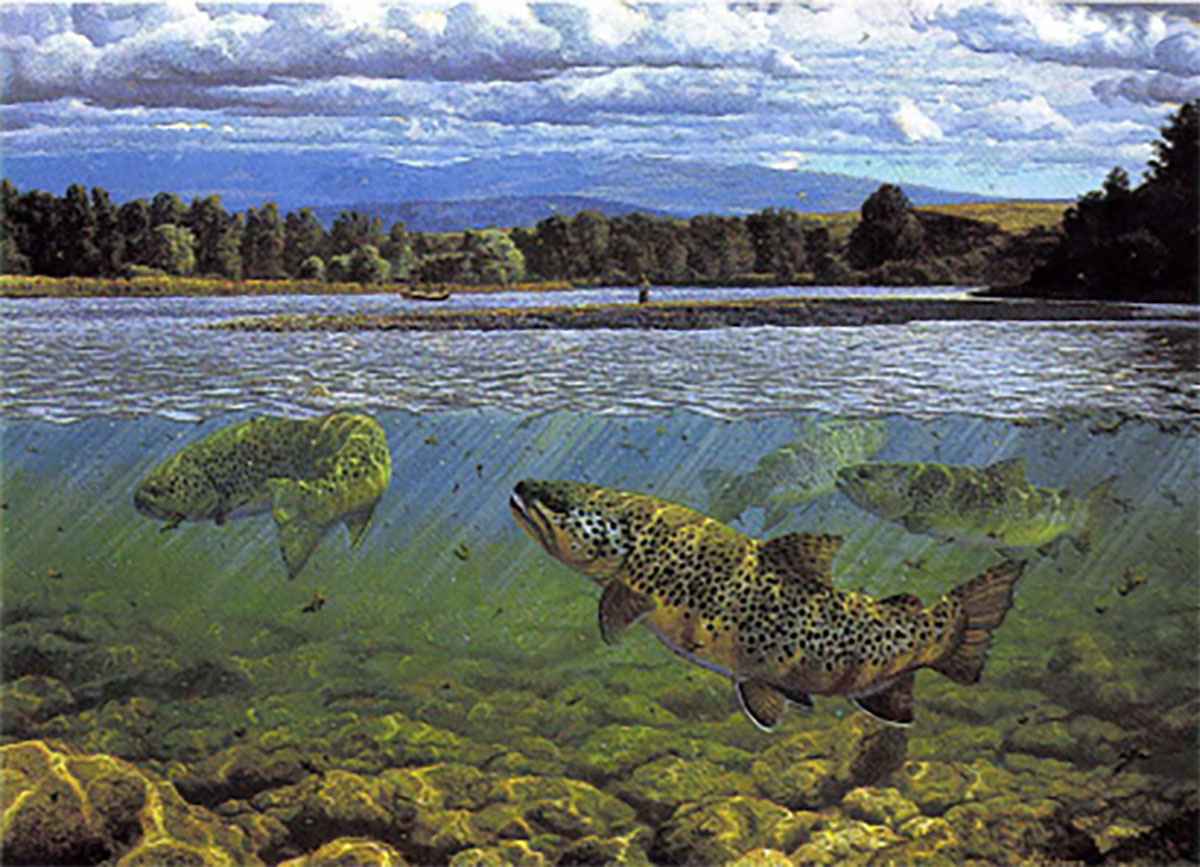

Michael Sieve is widely hailed as one of the America’s foremost painters of wild animals. Sieve has spent more than 40 years seeking inspiration in the natural world and channeling it into captivating images that can now be found in private and public collections around the world. Buy Now

Michael Sieve is widely hailed as one of the America’s foremost painters of wild animals. Sieve has spent more than 40 years seeking inspiration in the natural world and channeling it into captivating images that can now be found in private and public collections around the world. Buy Now