From the 2008 Sept./Oct. issue of Sporting Classics.

This is the way things were done, once upon a time.

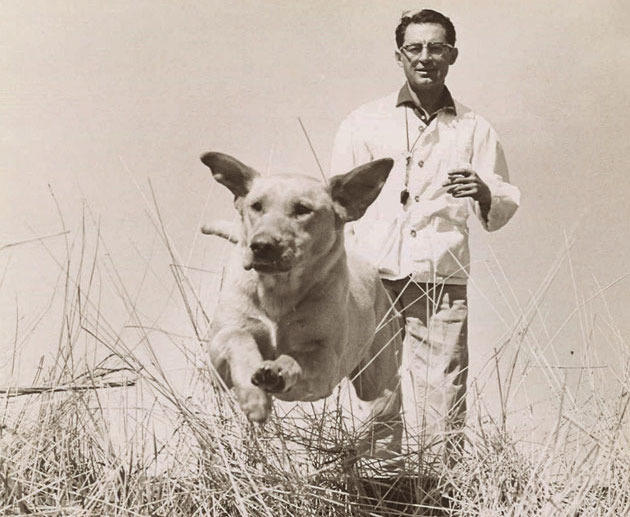

It was early in Joe DeLoia’s career as a professional retriever trainer—1949, to be exact. He’d been in the Army K9 Corps during the war, where he learned the principles and mechanics of training and where his ability to read a dog’s body language and anticipate its behavior left his superiors groping for explanations.

“They’d ask, ‘How did you know the dog was going to do that?’ ” he recalled. “I had no answer—but I always knew.”

He returned to his native St. Paul after the war, but it wasn’t long before a syndicate of retriever enthusiasts in Duluth made him an offer he couldn’t refuse: If he’d move there and set up a kennel, they’d kick in some seed money and throw plenty of business his way. They already had a property lined up, 20 acres and a nice home near Pike Lake, a few miles northwest of the city. The mortgage was $29 a month.

“I could tell you a lot of stories about that dog—but when I tell them, I don’t believe them myself.”

He hit the ground running, and by ’49 he’d already bred and trained one of the finest young retrievers in the country, a strapping black Lab named Massie’s Sassy Boots. Joe’s friend Art Massie was his owner, and between the two of them, they placed Boots 21 times in 22 field trial starts. The dog was so precocious that he was competing in All-Age stakes by the time he was 15 months old.

Massie wasn’t looking to sell Boots, but when a small fortune was offered him, he couldn’t turn it down. Joe delivered the dog to the famed Hogan Kennels, where the fine pro Frank Hogan would take over his training. Once he got there, though, a dispute developed over the price. Joe insisted that it was $3,200; Hogan countered that they’d agreed on an even $3,000. Both men had their owners’ full proxies, so when Hogan suggested they settle the matter by shooting a round of skeet, Joe, who’d been on the skeet team during his Army hitch, was all for the idea.

They both ran 24 straight, but when Hogan smoked his 25th, the pressure got to Joe and he dropped the last bird. Hogan split the difference and wrote out a check for $3,100. Massie’s Sassy Boots, of course, won the National Retriever Championship in 1956 and was eventually enshrined, along with Frank Hogan, in the Retriever Field Trial Hall of Fame.

It’s a good story but it gets even better. A few weeks after that transaction, Joe got a call from the express office at the Duluth train station. They said they had a dog there with his name on the crate. Joe wasn’t expecting any dogs for training or breeding but he went down to the depot and found a gorgeous, fully trained English setter—a gift from Boots’ new owner.

Now that’s Old School.

“I drove right to the woods and took that setter grouse hunting,” Joe told me a couple years ago, when I had the privilege of spending an afternoon listening to him reminisce about his life and career. “I could tell you a lot of stories about that dog—but when I tell them, I don’t believe them myself.”

Although for the most part he stuck close to home, by the mid-1950s Joe DeLoia’s reputation among knowledgeable retriever people was second-to-none. George Murnane, the head of the august Wall Street investment firm Lazard-Frères and a man who had the ear of the most influential and powerful people in the world, wanted Joe to train privately for him at his estate on Long Island. The package included a house, a car, the best schools for his children, the list went on.

“They weren’t just great dog trainers . . . They were the best guys in the world.”

For a young man who’d grown up in the St. Paul neighborhood known as Swede Hollow, supplying pheasants, ducks and rabbits to the 29 Italian families who lived there (and who for all intents and purposes were one family), it was a dream come true. But that was the problem: Joe’s roots in Minnesota ran too deep. He could never bring himself to leave, not even for the kind of money, and the kind of prestige, that George Murnane could offer.

He did, however, work for Murnane as an independent contractor, as he did for all his clients in his nearly 60-year career as a professional trainer. It was Joe, in fact, who convinced Murnane to buy the black Lab puppy that would become Spirit Lake Duke, the 1957 and ’59 National Retriever Champion.

“Mr. Murnane never dialed a phone in his life,” Joe said. “He always had his secretary do it. I’ll never forget something he told me: ‘When you do things for me at my suggestion or direction, you are my guest portal-to-portal. But I don’t want you eating wieners and charging me for steak.’”

It was a different world. In those days when a well-placed, well-timed marble was the method of choice for long-distance “correction,” someone at Ford thought the company could generate a little favorable press by fashioning custom aluminum slingshots for four of the country’s top retriever trainers. Joe was one; the other three were Cotton Pershall, Orin Benson and Charles Morgan.

“They weren’t just great dog trainers,” Joe will tell you, adding the names of Frank Hogan, Tommy Sorenson and Billy Wunderlich to the list. “They were the best guys in the world.”

He was a trainer’s trainer, and a hunter’s hunter. He loved waterfowling, but as a grouse hunter he was legendary. John O. Cartier, the longtime Outdoor Life field editor, called him “the most knowledgeable grouse hunter I’ve ever met.” He knew the bird’s habits so intimately that he could predict where they’d be not only day-to-day, but hour-to-hour.

And long before the term “pointing Labs” entered the vernacular, the Labs that were Joe’s personal hunting dogs always pointed. According to Joe, this wasn’t something he taught them but something they simply learned on their own. When one of his Labs out-pointed the pointing dogs at the 1984 National Grouse and Woodcock Hunt in Grand Rapids, Minnesota, it caused such a furor that Joe never went back.

He didn’t need the hassle, and besides, he had all the grouse he wanted, along with plenty of sharptails, the occasional pheasant and woodcock, and scads of ducks and geese at his hunting camp in the willow and wild rice boglands west of Red Lake. He’d stumbled onto the place in 1945, when it was nothing but a couple of shacks left behind by a crew of casket-makers. It’s much-improved since then, although it’s still nothing fancy—just the way Joe likes it. He’s been a guest at the poshest hunting camps in North America—the Daytons’, the DuPonts’, Nilo, Remington Farms—but he wouldn’t trade his for any of them.

Sadly, Joe’s hunting days are over. Now 91, his memory comes and goes, and his health in general is precarious. His family, including Lorraine, his wife of 67 years, recently made the hard decision to place him in a long-term care facility. When he’s feeling up to it, though, his friends take him to the meetings of the Duluth Retriever Club, among whose membership Joe is a kind of Godfather and patron saint. He is truly a beloved figure, a man of unimpeachable integrity and extraordinary generosity, a man of a type they don’t seem to make any more—the last of his breed.

This fall, when you gather at your own hunting camps in the company of great friends and grand dogs, raise a glass to Joe DeLoia. +++

Be sure to read Davis’ column in forthcoming issue of Sporting Classics.