Over Jim Harrison’s almost 50-year-long career, the Michigan-raised author has established himself as one of the most visceral and muscular outdoor writers, with classics such as True North and A Good Day to Die to his name.

While incredibly prolific—cranking out a book nearly every year since 1965—Harrison has inspired almost as much writing as he’s produced, thanks to his cantankerous and rollicking demeanor.

Below we’ve provided links to the six most essential articles about Harrison ever published, as well as excerpts from each.

“The Last Lion”

by Tom Bissell. Outside, August 2011.

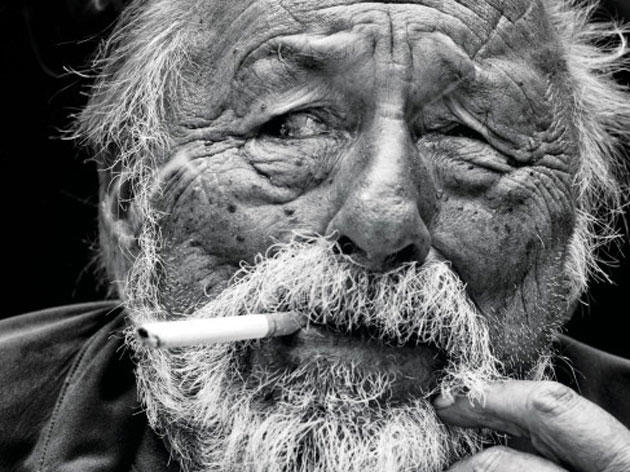

If you are describing Jim Harrison physically, you are pretty much forced to start with his eye. When he was seven a young girl, her motives unknown, pushed a broken glass bottle into his face, permanently blinding his left eye. When Harrison looks at you straight on, his left eye appears almost cartoonishly miscentered, as if he has taken a blow to the head and needs another, corrective blow to fix the problem . . .

In 1962, when Harrison was 25, he delayed the start of his father and sister’s hunting trip by debating whether he should accompany them. In the end, he decided not to. Judith, Harrison’s younger sister, was the only member of his family who shared his obsession with art and literature; the day Harrison waved goodbye to her was the last time he saw her alive. A few hours later, a drunk driver plowed into his father’s car. There were no survivors. When I asked about these events, Harrison said that his father’s and sister’s deaths “cut the last cord that was holding me down.” Soon after their funeral, he wrote the first poem he was able to consider finished . . .

In the Key West, Florida, of the early 1980s, McGuane, Caputo, Harrison, and several other writers and artists often gathered to fish and destroy themselves. Harrison described for me a notably druggy Key West convocation, during which he was sticking a straw in “a big Bufferin bottle of great coke. We didn’t even bother doing lines.” When he returned home to Michigan, he could not remember his cat’s name.

“The Art of Fiction No. 104”

Interviewed by Jim Fergus. The Paris Review, Summer 1988.

Interviewer:

This idea of movement and the metaphor of the river, seem to be central to your work.

Harrison:

It’s the origin of the thinking behind The Theory and Practice of Rivers. In a life properly lived, you’re a river. You touch things lightly or deeply; you move along because life herself moves, and you can’t stop it; you can’t figure out a banal game plan applicable to all situations; you just have to go with the “beingness” of life, as Rilke would have it. In Sundog, Strang says a dam doesn’t stop a river, it just controls the flow. Technically speaking, you can’t stop one at all.

“Jim Harrison Can Make You a Better Animal”

by John Avlon. The Daily Beast, September 2010.

Harrison lumbers into the lobby of Murray’s Hotel, his face like a weathered tomato and topped with thinning gray hair, windswept and spiked up at all angles, punctuated by a goatee hanging off his prodigious chin. He is an immediately warm and welcoming presence, offering easy greetings to the woman behind the counter. He has a rasping, rich laugh, and a higher-than-expected voice capped with a flat Midwestern accent courtesy of his Upper Michigan Peninsula background . . .

One the mysteries of Harrison is how his love of remote American locations—where his stories almost always take place—is balanced by his times as a scriptwriter in Hollywood hanging out with Jack Nicholson in the ’70s, fishing in Key West, and periodic indulgences in New York and Paris. “Well I have to have both. If all I did was pretend I was Wilderness Jimmy I would go stale. You know, I fish maybe 100 days of the year and bird-hunt, but if I didn’t go to Paris once or twice a year, I’d be crazy.”

“A Northern Michigan Literary Icon”

Interviewed by Jerry Dennis. My North, 2014.

Interviewer:

I know the place, right along U.S. 2. Great fishing. You often describe yourself as an “outdoorsman and a man of letters.” Why is being outdoors so important to you?

Harrison:

Very early my dad would take me trout fishing because you know I’d had my eye put out and I needed extra attention. I remember asking him the difference between animals and us and he said, “Nothing. They just live outside and we live inside.” Which struck me very hard at the time, because I could look at animals and say, “I’m one of you.” The real schizophrenia of the nature movement, if you ask me, was to think you could separate yourself from nature. Even Shakespeare says “we are nature, too.” So there’s this sense of schizophrenia to think you’re different or more important than a bird.

“Pleasures of the Hard-Worn Life”

by Charles McGrath. The New York Times, January 2007.

There was plenty for dinner nonetheless: some doves he had killed a day or two before, antelope from a recent hunt up in Flagstaff and elk loin that a friend had sent from Montana. Mr. Harrison, a self-described “food bully,” has very particular ideas about cooking. He thinks rosemary should be banned. He has no use for huge restaurant-style ranges: “Why should I spend $7,000 for a stove when I could spend $7,000 on food?” And he doesn’t believe that game, birds especially, should be tarted up with elaborate sauces. “As the French say, game birds taste best at the point of the gun,” he said.

So he roasted the doves over a mesquite fire in the living-room fireplace, after first basting them with butter and lemon juice and squirting a little Worcestershire sauce into the body cavities, just “for aromatic purposes.” Then, an American Spirit dangling from his lip, he set to sautéeing the antelope and the elk in a hot skillet on top of the electric stove while Zilpha and a visiting golden retriever scurried underfoot. The secret, Mr. Harrison explained, was to cook the meat very quickly in lardo, the neck fat of a pig that, for the final months of its life, dines on only fruit and milk. The elk was served with polenta, prepared with egg and Gruyère cheese by Linda, and there was plenty of red Bandol to drink, along with a couple of between-course cigarettes.

“Birnbaum v. Jim Harrison”

Interviewed by Robert Birnbaum. The Morning News, June 2004.

Interviewer:

You say you can write anywhere but might there be a different feeling where ever you might be—in the center of the country you are not near the concentration of microwaves and such—doesn’t Montana feel different?

Harrison:

Well, yeah. I was thinking last year in—not to overplay this hand but it’s interesting. But I was reading a galley by a guy named Mark Spragg coming out by Knopf, an intriguing book. And I was wondering if I agreed with the character who had been injured by a grizzly bear. OK, then I thought, “What am I thinking about?” Last year there were two grizzly attacks on humans within 15 minutes of our home, and last winter a pack of wolves killed 28 sheep within view of our bedroom window. Plus my dog got blinded by a rattlesnake in the yard.

+++

Be sure to subscribe to our daily newsletter to get the latest from Sporting Classics straight to your inbox.

All photos and text excerpted from their sources. Cover image courtesy of Steve Rhodes/Flickr.