“I don’t want to bunt every time. I’m going to swing for the fence.”

Jay Kemp is explaining how his most successful painting came to life. He wanted to paint a big bull elk, he says, running a hand through his hair, green eyes looking beyond the glass doors of his home studio in Gainesville, Georgia.

“I wanted him to be like he was bigger than full frame, and up in your face.”

Working Lab was selected as a Duck’s Unlimited print in 2011.

Kemp had the art expertise and wildlife experience — including an in-your-face encounter with a trophy bull in the Canadian Rockies. But people told him a painting of an up-close elk wouldn’t sell. Few buyers would be interested. Don’t waste your time.

Kemp painted it anyway.

In his basement studio on the shores of Lake Sydney Lanier, a full-sized print of the 3-by-4-foot original stares down visitors. The elk is in mid-bugle, neck out, chin up, frosty breath blowing from a half-open mouth. Antlers rise with the curling condensation. Thin mist steams from the thick fur. A scraped sapling and sloping branches frame the massive animal against deep forest.

Outside, Lake Lanier shimmers in the afternoon sun.

Inside, the elk captivates. It did the same at the 2012 Southeastern Wildlife Exposition, a premiere show for wildlife art in Charleston, S.C. Internationally acclaimed artist Carl Brenders was among the admirers.

Writing to organizers of the 2013 Expo, Benders said Kemp “might be, in my eyes, one of the greatest [wildlife artists] of today.

“Of all the wildlife art that I have seen in my 25-year career, his big painting of a bugling elk is the only one that brought tears to my eyes…It was not a painting…it was the elk itself. One must be a hell of an artist to realize such a piece. Jay’s work is outstanding; he is my favorite of the new generation.”

The elk original sold for more than $30,000 and served as a springboard to Kemp’s selection as the featured painter at the 2014 Southeastern Wildlife Exposition.

Yet the painting is also an exclamation point to the artistic development of this soft-spoken North Georgia native. A professional artist since 1991, Kemp is painting what he wants, how he wants.

He has moved from the small paintings that marked the start of his career to whatever size canvas a subject demands. He has switched from the fragile medium of watercolor and gouache to acrylic, with which he can be “relentless” in shaping an image. Although recognized for ultra-realistic detail, Kemp is drawing attention tor his ideas, composition and design, more subtle but critical aspects.

He is pursuing paintings he wants to create, not what publishing companies might favor.

“You don’t pay attention to [commercial] successes or failures,” he says.

In a career heavy on accolades, Kemp’s success allows him to work with organizations he supports, such as Ducks Unlimited, the Quality Deer Management Association and National Wild Turkey Federation.

He stresses, however that it remains all about the paintings. If they raise money to help conserve the animals, plants and natural habitats he loves, “that’s icing on the cake.”

In the late 1980s Kemp attended Anderson College in upstate South Carolina on a baseball scholarship. Practices often lasted until dark. Players regularly hit Hardee’s afterward. But the third baseman from Gainesville was feeling a growing hunger for something else.

The restaurant was decorated with wildlife art prints. “I would eat at a different booth every time to look at the prints,” Kemp remembers. He would also dream: Maybe he could do something like that.

There was no epiphany. Yet Kemp soon followed his heart. Instead of playing baseball and studying engineering at a four year school, he accepted an art scholarship to North Georgia College & State University, 30 minutes from Gainesville. His major: art marketing. Then his ability to draw caught the eye of professor Win Crannell.

If you work hard, Crannell told him, you can make a living at this.

“I didn’t believe him,” Kemp says, “but I listened to him.”

Now Kemp’s work sells for thousands and is favorably reviewed by wildlife art masters like Brenders and Robert Bateman. All of which leaves this married father of two humbled. ”I’m just a red-necked guy from Georgia,” says Kemp, 46.

He is also a hunter and angler. Mounted bass line part of a wall in his studio. His boys sometimes spend mornings in a deer stand with him. He is passing along his passion for the outdoors.

Through art, that interest can reach Further. Kemp hopes his work, like that of other artists and photographers, raises awareness of wildlife and support for conservation. It can, he says, reveal to a public largely disconnected from nature “what’s out there to protect.”

Showing what’s in his paintings is more difficult. Viewers may focus on the fin er-than-life detail of a red fox’s fur or the rich colors illuminating a preening egret. The complexity, though, runs deeper.

One of his pieces depicts Canada geese flying across a fog-cloaked field. In his early ’20s, Kemp had photographed geese near Lake Lanier. The memory stuck. The painting its parked is much different.

The shape and placement of a central tree and its branches, along with thick haze and pale clouds, hint at the lift of wings straining for altitude. The ragged flock appears out of shadowy fog on the light. The birds’ ascent is spurred by lines in the grass angling upward toward a field edge lost in vagueness. The wing tips are blurred. Adding detail would have made the image flat, Kemp explains.

Every part of his paintings is planned. Kemp says elements are thought through first as shapes and second as wildlife or natural features. ”I’m looking for a certain mood. I want it to have depth . . . I want [it] to be good.”

Rendering for extreme detail and texture can push a painting to capture imagery no photograph can match. Yet, adds Kemp, “The details cannot carry the message of a painting.” Ideas, design and elements such as light are foundational and “way more important than detail.”

The foundation of Kemp’s career is part talent and expedience, part hard work and striving.

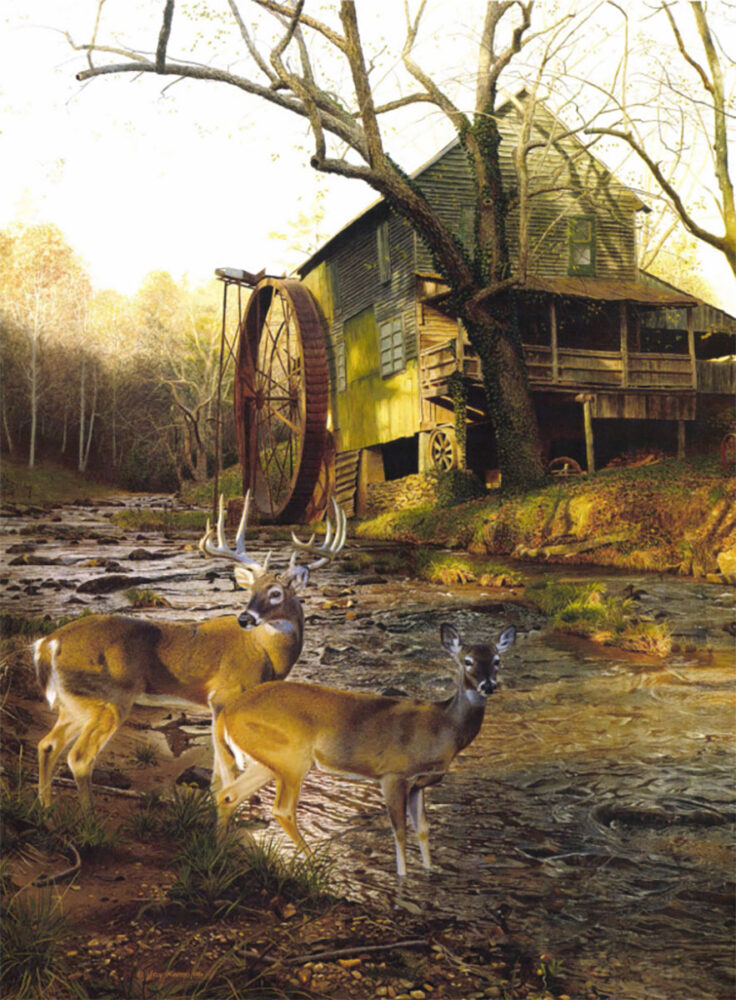

Mill Creek Crossing, which depicts Healan’s Mill not far from the artist’s Georgia home, was published in a limited edition by the National Wild Turkey Federation.

He spends hours outdoors. He studies composition and design, areas in his art he considers weaknesses. He welcomes reviews. He is ruthless in self-critique. Like many artists, Kemp sees his flaws, not his strengths. It is a mental fight, he admits. The challenge is to improve.

“I don’t want to bunt every time. I’m going to swing for the fence.”

That attitude made the elk painting. Kemp had chased elk for two weeks at Jasper National Park in Alberta, trying to find a herd or bull elk to shadow. He was praying for acold, frosty morning. He had an idea. He wanted to see it fleshed out.

Kemp awoke before dawn one morning to find his windshield coated with ice. Excited, he scraped off enough to see and began driving.

He spotted a herd of cows. The nan elk bugled. Kemp pulled onto the roadside. The bull sounded close; somewhere near a liver that curved below. He scrambled and slid down a steep embankment. At the bottom, he almost stumbled into the bull. It stood 20 feet away.

“This joker turned and bugled right in my face!” Kemp recalls with a grin.

The memory later became shapes, and color, and another accomplishment in an accomplished career.

Kemp says painting sometimes intimidates him. At the same time, it’s the most natural thing.

”When I’m painting, I don’t feel like I’m wasting my time. It feels like I’m doing what I’m meant to do.

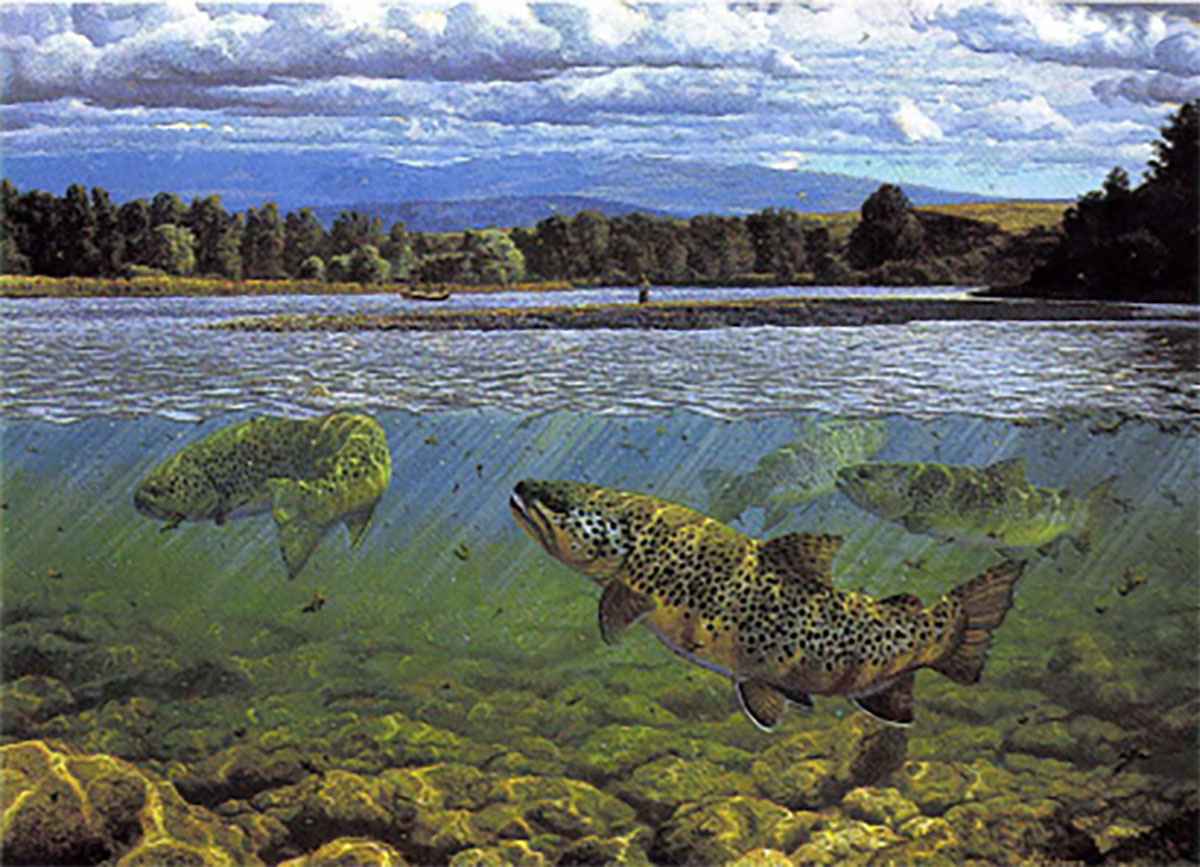

Michael Sieve is widely hailed as one of the America’s foremost painters of wild animals. Sieve has spent more than 40 years seeking inspiration in the natural world and channeling it into captivating images that can now be found in private and public collections around the world. Buy Now

Michael Sieve is widely hailed as one of the America’s foremost painters of wild animals. Sieve has spent more than 40 years seeking inspiration in the natural world and channeling it into captivating images that can now be found in private and public collections around the world. Buy Now