The term “sportsman” is often applied to hunters, fishermen and trappers, but is that the correct moniker?

I even use it myself, grudgingly, because that term is recognized and aids communication. But is that what we are? Are we engaged in a sport? I think not.

“Sport” and “sportsman.” When I think of those words, I think of polo players, yachts, football, “extreme” pursuits, hordes of kids ferried frenetically from one soccer field to another. These poor kids never get to play on their own, outside, where they might encounter an insect, bird, flower or deer.

I think of people chasing some projectile around in an artificial enclosure, basking in the adulation of the adoring crowd.

I think of an activity with little purpose except entertainment and diversion.

I think of winning and losing and opponents and competition, which are fine in athletics but sorry reasons for hunting.

Hunting is not a “sport.” A cheating and dishonest player of sports is disagreeable; a cheating and dishonest hunter is corrupt.

The animals we hunt are not opponents. It is an abiding mystery that, while a hunter may claim the life of the quarry, the animal is never seen as vanquished or defeated. As we sit by an animal we have killed and feel its body heat still within it, we feel humility and some sadness. This is not the time nor place for high fives or fist pumps. Those behaviors are for the end zone of the junior-high mentalities in the NFL.

No, not there, with that animal in that moment of moments that eclipses all others in our hunting experience. The animal is held in the hunter’s mind and memory as a sacred remembrance.

And sacred is the right word for it, whether in ancient times or the modern day. Hunters hold their quarry and their pursuit as sacred. Hunting is not a game; hunters are not players. Sports are contrived and theatrical, but hunting has been a part of the life of humans since we first appeared.

And sacred is the right word for it, whether in ancient times or the modern day. Hunters hold their quarry and their pursuit as sacred. Hunting is not a game; hunters are not players. Sports are contrived and theatrical, but hunting has been a part of the life of humans since we first appeared.

All of the old ones, the ancient ones, felt the same power in it. They have said so in their writings, if they wrote, or in their cave paintings if they did not. Doubters might well consider the significance of entertainment versus death.

Aldo Leopold in Sand County Almanac summed up what is required of a hunter:

“A peculiar virtue in wildlife ethics is that the hunter ordinarily has no gallery to applaud or disapprove of his conduct. Whatever his acts, they are dictated by his own conscience, rather than by a mob of onlookers. It is difficult to exaggerate the importance of this fact.

“Voluntary adherence to an ethical code elevates the self-respect of the hunter, but it should not be forgotten that voluntary disregard of the code degenerates and depraves him.

“Ethical behavior is doing the right thing when no one else is watching – even when doing the wrong thing is legal.”

Hunters today leave the comfort of home to enter the wild world, with its dangerous weather, its discomforts and its pain. The hunter knows his chances of success are low, often just 15 to 25 percent. The hunter knows the odds are stacked against him, but he believes his skill, scouting, willingness to work harder and hike further, and ultimately marksmanship will overcome the odds. Often it doesn’t work out, but the hunter enters the hunt believing it will.

Every year 50, 60, 70 hunters out of every 100 come home empty-handed. And they all go back out the next year, optimistic again. Why? Because it is the hunt as much or more than the kill. One never feels as alive as when lashing on those boots, loading that magazine, shouldering that rifle and setting out into the hills and fields and marshes to hunt and maybe kill.

If the quarry is taken, that animal becomes part of that hunter forever. The hunter’s being soars in a spiritual partnership with the spirit of that animal, and the hunter is humbled and blessed. That animal becomes part of that hunter’s soul, and its memory lives on in that hunter forever.

Ancient human artists showed their love, reverence and awe of animals in their paintings on cave or canyon walls. They most often depicted humans as stick figures of little detail while rendering the animals with realistic characteristics and attention, giving them beauty and precise detail. Their work showed they held their quarry in high esteem, as current hunters of today.

Ruark said it best:

“…If you properly respect what you are after, and shoot it cleanly and on the animal’s terrain, if you imprison in your mind all the wonder of the day from sky to smell to breeze to flowers—then you have not merely killed an animal. You have lent immortality to a beast you have killed because you loved him and wanted him forever so that you could recapture the day…”

Hunters understand their responsibility to the fair-chase pursuit of game, responsibility to the resource and habitat, limiting take to what is sustainable, the requirement that they support wildlife and wild places with sweat and treasure to ensure it remains. The hunter, the fisherman and the trapper do far more for conservation than any other segment of society.

No, hunting was never a “sport.” And it’s not today.

Note: This article originally ran in the Idaho Falls Post Register and the Idaho State Journal. It appears here in a slightly altered format.

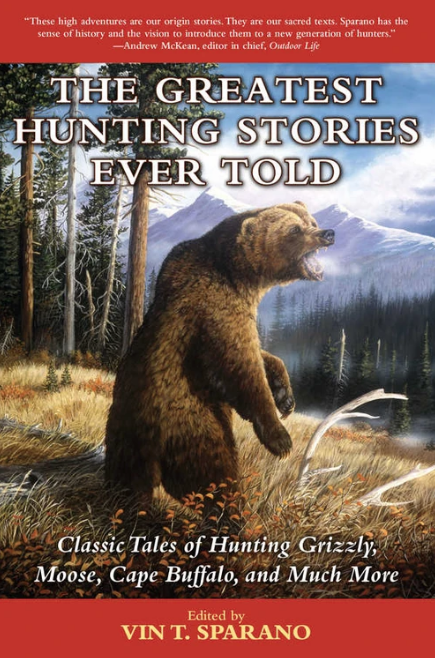

Now, for the forty million Americans who hunt, here is the perfect companion. The Greatest Hunting Stories Ever Told is a collection of true hunting tales, told by some of the most courageous and clever sportsmen. The quest for adventure has touched all these writers, who convey the drama, tension, stamina, and sheer thrill of tracking down game.

Now, for the forty million Americans who hunt, here is the perfect companion. The Greatest Hunting Stories Ever Told is a collection of true hunting tales, told by some of the most courageous and clever sportsmen. The quest for adventure has touched all these writers, who convey the drama, tension, stamina, and sheer thrill of tracking down game.

Included here are the experiences of Teddy Roosevelt in “The Wilderness Hunter,” of Jack O’Connor in “The Leopard,” of J. C. Rickhoff in “Wounded Lion in Kenya,” of Frank C. Hibben in “The Last Stand of a Wily Jaguar,” and of John “Pondoro” Taylor in “Buffalo,” among others. Buy Now