The Labrador retriever’s distinctions are many. If there’s one arena in which the Lab is utterly and incontrovertibly dominant, it’s retriever field trials.

The most popular purebred dog in America; the most popular gundog, too: the Labrador retriever’s distinctions are many. Still, if there’s one arena in which the Lab is utterly and incontrovertibly dominant, it’s retriever field trials.

Think of it this way: If the field trial Lab were a sports franchise, it’d make all the other legendary sports franchises—the Yankees of Babe Ruth, the Celtics of Bill Russell, the Packers of Vince Lombardi—look like a bunch of also-rans.

Since 1951, all the winners of the National Retriever Championship have been Labs. And since the inception of its companion stake, the National Amateur Retriever Championship in 1957, only one winner has not been a Lab.

In the retriever field trial kingdom, Labs rule.

Tubb, a National Amateur Field Champion in 2014, is registered as NAFC-FC Texas Troubador.

On the face of it, this seems puzzling. The Lab, the golden and the Chesapeake have all been bred over hundreds of years and dozens of generations to do pretty much the same thing: run and/or swim to where a gamebird has fallen, pick it up and bring it back. Put a well-trained individual of any of these breeds in a duck blind and watch him do his intended job over the course of a season, and there probably wouldn’t be much to choose from between one and the other.

What is it, then, about field trials, which are essentially competitive tests of retrieving ability, that so lopsidedly favors the Lab? What do Labs have that goldens and Chessies don’t?

The first retriever field trial in the United States was held on a private estate near New York City in 1931. Affluent Eastern sportsmen—Marshall Field, W. Averill Harriman, August Belmont, the list went on—had begun importing Labs from Great Britain in a big way in the 1920s. The breed’s original role here was to serve as “pick-up” dogs during elaborately orchestrated driven pheasant shoots—the same role these socially prominent sportsmen had witnessed Labs perform, impressively, on shooting holidays in the British Isles.

John Russell prepares to send Tubb at the National Amateur in Ronan, Montana.

Of course, Messrs. Field, Harriman, et. al. needed people to train and handle these Labs, also to manage their kennels and oversee the pheasant-rearing on their estates, so they hired and imported their own gamekeepers as well. Most came from Scotland, with a smattering from England, Ireland and Wales.

These first-generation keepers, finding themselves in a foreign country but in generally close proximity to one another (most of the Lab-owners’ estates were on Long Island or in the Hudson River Valley), were a tight-knit bunch. Back home they’d enjoyed the friendly competition of field trials; why not in America?

In any event, that first field trial—which consisted of braces of Labs walking at heel and being sent on command to retrieve as pheasants were flushed and shot ahead of them—came off. Beyond the insular community of keepers and their employers, however, very little note was taken of it.

But then, in 1932, a group of Chesapeake enthusiasts held a field trial that focused on retrieving from water. “That event proved to be a disaster for the Labrador,” wrote Richard Wolters in his book Duck Dogs, “because the tests were all water work and the Labs were field dogs . . . But it so happened that this ‘disaster’ became the lucky fluke that cemented the future for the Labrador in the United States.”

Once the keepers had had a chance to train their Labs to retrieve from water—an easy task, given that the breed descended from dogs developed on the coast of Newfoundland expressly for water work—they came back and, in Wolters’ words, “beat the Chessie at its own game.”

But the golden retriever, too, was coming on strong. Indeed, two of the first four National Retriever Championships, and four of the first 11, were won by goldens. And while it never broke through to win a National, the Chesapeake continued to have a significant field trial presence in those early years as well.

Over time, though—and, in particular, as field trials changed from simulations of “real world” hunting situations to invented tests of diabolical difficulty—the Lab gradually but ineluctably asserted its dominance. You can point to any number of reasons for this, but the catalyst was the introduction, in the mid-1930s, of the blind retrieve. Or, as it’s more commonly known, “the blind.”

These days the blind is such a familiar part of the retrieving repertoire that it’s hard to imagine a time when it didn’t exist, but in fact credit for the innovation goes to one man: a Scottish gamekeeper named Dave Elliot who came to America in 1934 and, to quote Wolters again, “did more to change and advance field trials in this country than any other person.”

Inspired by watching herdsmen handle their sheepdogs at long distance via whistle and hand commands, Elliot devised a similar system for retrievers. If one of his dogs went for a retrieve but drifted off the proper line, he’d stop it with a whistle blast. The dog would then turn, sit and, watching Elliot intently, wait for a hand signal to point it in the proper direction to find the bird and complete the retrieve. This same basic system, with a few refinements, remains in use today.

The introduction of the blind retrieve opened up an undiscovered country of possibilities. Before the blind, all retrieves were “marks”—retrieves in which the dog sees the bird fall and “marks” the location in his visual memory. When marks were the exclusive name of the game, the Big Three retriever breeds competed more-or-less on equal footing.

But as mastery of blinds increasingly became the litmus test that judges relied on to separate the winners, the Lab left the golden and the Chessie in the dust. And this process only accelerated as the distances became longer and the necessity of the dog’s maintaining a straight line, despite all manner of fiendish diversions contrived to influence him off that line, became all-important.

Is the Lab somehow inherently better at running or swimming in a perfectly straight line than the golden or the Chesapeake? Of course not. What the Lab is better at, as the field trial community figured out pretty early in the game, is responding favorably to the specialized training necessary to inculcate the behavior. It requires a high degree of what retriever trainers somewhat euphemistically refer to as pressure, a good definition of which is this one, from Tom Quinn’s The Working Retrievers:

“Pressure is the trainer’s insistence on task performance through methods of force or implied force.” Force, as defined by Quinn, is “the physical means and ability to discipline a dog and compel him to perform tasks—some of which may be unpleasant or boring and contrary to his natural choice, inclination, and will.”

The e-collar, needless to say, is by far the most effective “force delivery mechanism” ever invented, especially for enforcing “correction” remotely, i.e., at long range. In the old days, trainers routinely used slingshots, BB guns and even small-gauge shotguns loaded with poppy seed-sized “rat” shot for the same purpose.

No, I’m not kidding.

To put it as simply as possible, Labs, as a rule, can “take” the pressure of training for advanced blind retrieves, including holding that razor-straight line, better than goldens or Chessies can. Ultimately, this is the quality that has made the breed all but invincible in field trials—and beloved by professional trainers, to whom time is money and, again as a general rule, are able to make more progress with a Lab in a given amount of time than they’re able to make with a golden or a Chessie.

And that, ladies and gentlemen, concludes today’s history lesson.

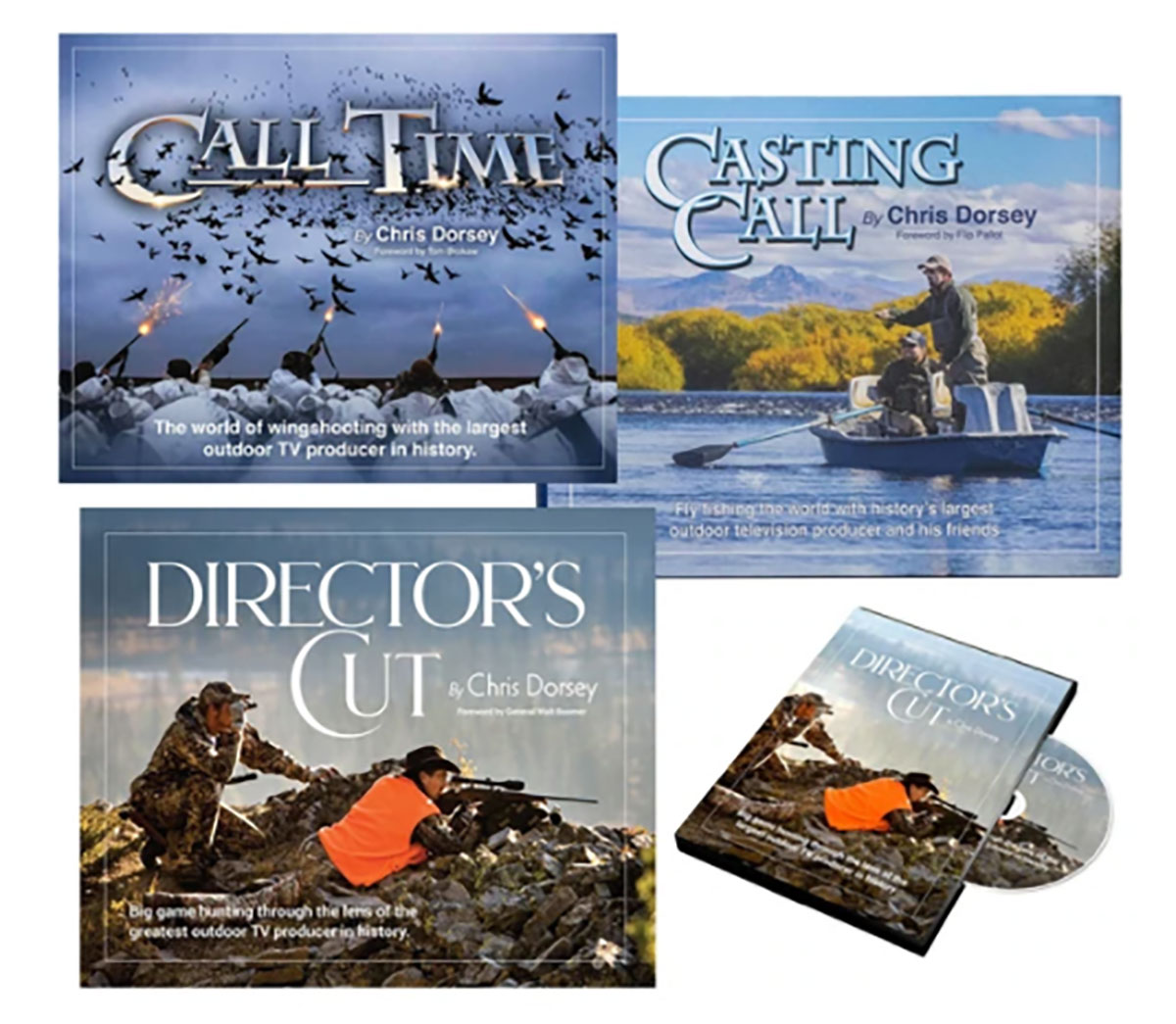

Featuring Casting Call, Call Time and Director’s Cut this bundle includes a book and film production more than 30 years in the making. Author and Executive Producer Chris Dorsey, along with a team of the world’s best sporting life photographers and cinematographers, embarked on expeditions to distant corners of the globe to create an indelible portrait of wingshooting, fly fishing, big game hunting and the great outdoors. Each large-format 250+ page book includes a DVD with corresponding film shot on location for every chapter. Buy Now

Featuring Casting Call, Call Time and Director’s Cut this bundle includes a book and film production more than 30 years in the making. Author and Executive Producer Chris Dorsey, along with a team of the world’s best sporting life photographers and cinematographers, embarked on expeditions to distant corners of the globe to create an indelible portrait of wingshooting, fly fishing, big game hunting and the great outdoors. Each large-format 250+ page book includes a DVD with corresponding film shot on location for every chapter. Buy Now