Before there was an Eldridge Hardie, a Tom Quinn or a Bob Abbett; before there was a William Harnden Foster or a Percival Rosseau; even before there was an Edmund Osthaus or a Gustav Muss-Arnolt, there was John Martin Tracy. And J.M. Tracy, to use the name he signed to his canvases, was nothing less than America’s first great painter of sporting dogs.

From 1878, when the then 35-year-old artist received a commission from the St. Louis Kennel Club to paint Berkley, a champion Irish setter that the club sponsored, until his untimely death in 1893 at the age of 49, Tracy depicted virtually every important pointer and setter of the era—the very fountainheads of the breeds as we know them today.

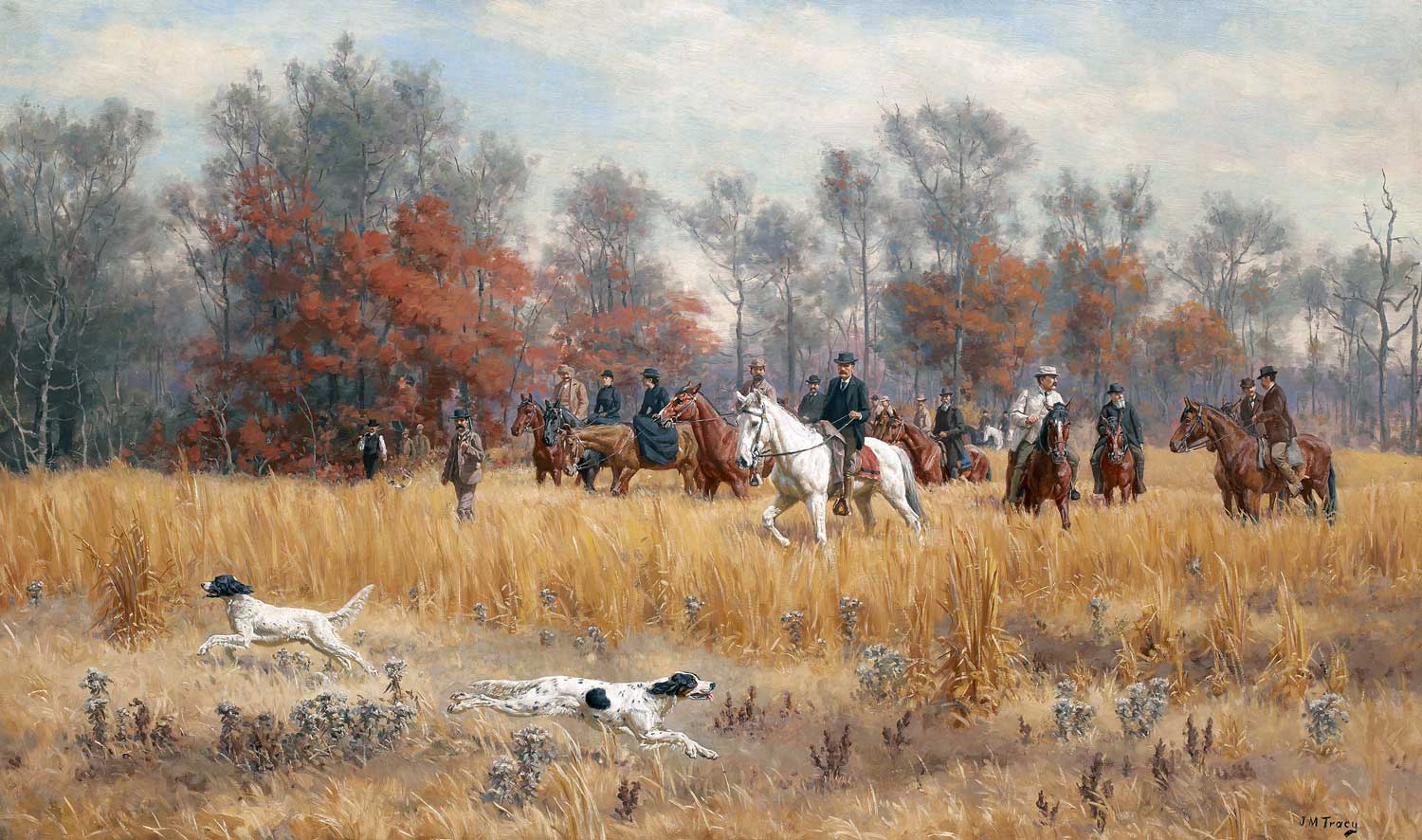

Southern Field Trials depicts the dogs Lightfield Deuce and Prince Lucifer. It was shown at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.

Other artists have painted dogs, and painted them well. But only Tracy was there to document the very beginnings of the American tradition.

He was no one-trick-pony, though. He wasn’t just a dog portraitist; he was a full-fledged sporting artist whose wingshooting scenes broke ground that was cultivated by a bevy of successors including A.B. Frost, Lynn Bogue Hunt and A. Lassell Ripley.

As an anonymous writer for the New York Times observed in 1895, “J.M. Tracy was an artist to delight the hearts of all sporting men… He painted the hunter before the flock of birds, the dog with tail extended and paw uplifted as he stood quivering over the scent, and he did it all con amore (with love), faithfully, and with full understanding and knowledge of his subject.”

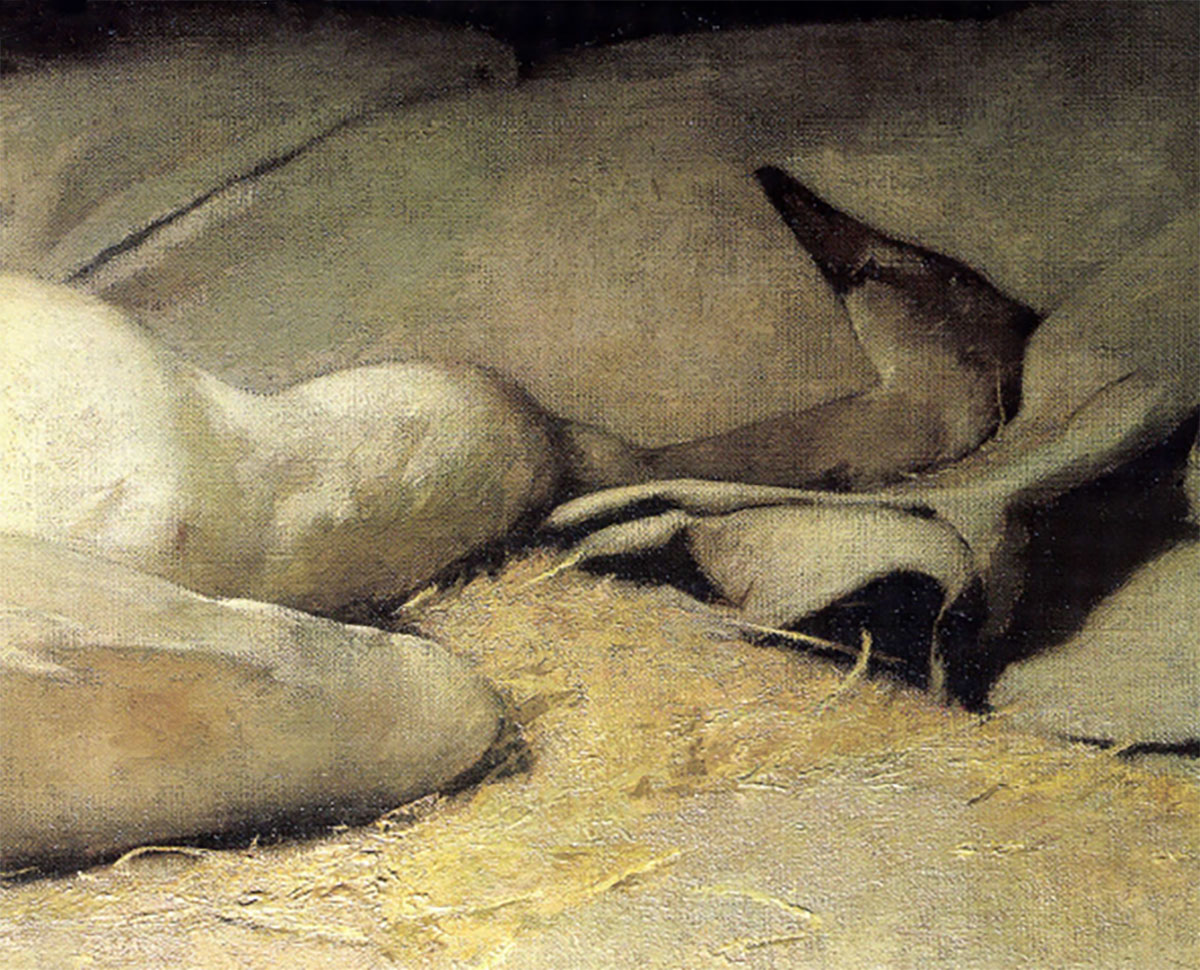

Marsh Shooting. This oil on canvas is a self portrait of the artist.

Tracy also did a number of paintings of field trial scenes, several of which were reproduced and sold as prints long after his death. These are the Tracy images most familiar to the sporting public at large: a brace of dogs, typically a pointer and an English setter, pointing and backing in the foreground, the handlers on foot behind them, the mounted judges and gallery in the rear. The sad thing is that while these dogs were undoubtedly actual field trial winners of the era, their identities have been lost.

Nevertheless, Tracy created a rich pictorial record of what was the formative period in the history of American pointing dogs, field trials and upland bird hunting. But while he will always be remembered as the chronicler of a golden age, the quality of his artistry is equally enduring. It shines forth brilliantly, undimmed by the passage of time.

His dogs pulse with energy and vitality. These are not the idealized specimens of Osthaus and Rosseau, but real flesh-and-blood, sinew-and-bone dogs of a type not terribly different from the pointers and setters that grace our kennels today. They’re beautiful, yes, but individualistic at the same time. Their genius is self-evident; it does not need to be idealized.

As a painter, Tracy had the whole package. His drawing was clean, fresh and authentic, and his sense of color was unerring. His palette emphasized the somber hues of autumn: the burnished chestnut of a blooded horse, the soft tan of a setter’s muzzle, the rich liver of a pointer’s ticking, the golds and russets and muted greens of hunting season. The sentiments of a leading art critic of the 1890s remain valid today:

The late John M. Tracy was recognized at home and abroad as a painter of the first distinction in the field of higher class sports, to which his art gave their proper dignity in the pictures he produced. His dogs and horses were portraits instinct (imbued) with life and full of character and expression; his landscapes scenes of actual nature, not mere backgrounds; and his sportsmen manly figures, taken from real life and with the action appropriate to their enjoyment.

Still, an undeniable aura of mystery surrounds John Tracy. While his art speaks for itself, many details of his life remain sketchy. This is particularly true of the period before 1878, when he first stepped into the national limelight.

From what little can be gleaned, however, his childhood, youth and early adulthood seem to have been extraordinarily tumultuous. The twists and turns began even before he was born, when his father, a radical abolitionist minister in the John Brown mold, was killed during an anti-slavery riot. Forced to fend for her three children and herself, Tracy’s mother, a strong, independent, remarkably “modern” woman, pursued a successful career as a journalist and later became a prominent figure in the suffrage movement.

Irish Setter on Point, Oil on canvas, c. 1890.

Tracy grew up in Rochester, Ohio, and after briefly attending Oberlin College, he transferred to Northwestern University near Chicago. He began his formal study of art there but hadn’t gotten very far when the Civil War erupted. Enlisting in the 19th Illinois Infantry, Tracy served with distinction, being wounded in battle twice and rising to the rank of lieutenant before the Confederacy gave up the ghost.

Following the war, Tracy embarked on a kind of personal and artistic odyssey. He picked fruit and taught school in southern Illinois for a couple of years, saving enough money to fulfill his dream of studying art in Paris. He spent two years there at the famous Ecole des Beaux Arts, then returned stateside where he may—or may not—have studied for a time at the California School of Design. He eventually ended up back in the Chicago area, writing and illustrating newspaper articles and becoming involved in a romantic entanglement that, as romantic entanglements tend to do, ended badly.

Seeking to make a fresh start, Tracy once again set sail for France. It was during this stint that he apparently rubbed elbows with John Singer Sargent and a number of other American expat painters who would go on to make names for themselves. He also got his love life back on track, marrying a French woman named Melanie Guillemin.

The newlyweds settled in St. Louis, where Tracy hung out his shingle as a portrait painter. The wives and children of the wealthy were his primary subjects until, sometime in 1878, the St. Louis Kennel Club approached him about doing the aforementioned portrait of Berkley, the club’s famous Irish setter.

That portrait proved to be the turning point of Tracy’s career. In the depiction of dogs—and, later, complete sporting scenes—he found his enduring métier. Soon, the owners of the country’s finest dogs were standing in line to commission him to paint their champions, or to portray their dogs and themselves as they partnered afield.

Soon, too, Tracy was being invited to judge the most important field trials and bench shows of the day (including Westminster), assignments for which his critically discerning eye and amazing powers of recall—it was said he could sketch virtually anything from memory—served him well.

In the early 1880s, Tracy moved to Greenwich, Connecticut. A few years later, he added a winter home and studio in Ocean Springs, Mississippi. Although he was only in his 40s, his health was already beginning to fail. Reflecting on Tracy’s visit to paint his portrait in 1887, the canine narrator of John Sergeant Wise’s Diomed: The Life, Travels, and Observations of a Dog mused: “I had always expected to see in Mr. Tracy a young, vigorous man. When he made his appearance I perceived at once that he was more gray, and bent, and older looking than I had expected. Such is the price men pay for fame…”

The price, indeed. In the early months of 1893, Tracy was working feverishly at his Ocean Springs studio to replace a group of paintings that had been destroyed by fire when his heart simply gave out. An obituary in the American Field attributed his death to “nervous prostration,” adding that it “brought to a close a life, the loss of which so many will regret and which will live forever in the annals of art.”

John M. Tracy was a groundbreaker, a man who found himself in the right place at the right time with the right set of skills. His paintings of bird dogs, field trials and wingshooting have rarely been equaled and never surpassed. To use the words of Nash Buckingham (who was a great admirer of Tracy’s), they depict a “vanished field gentility.”

Vanished, perhaps—but through the alchemy of Tracy’s art, immortal.

This article originally appeared in the 2019 November/December issue of Sporting Classics magazine.

Presents 150 paintings of upland bird hunters, waterfowlers and anglers. Readers will love his detailed depictions of many different breeds of gundogs. Throughout the book are sidebars relating to the general subjects of the paintings gleaned primarily from a lifetime of the artist’s own hunting and fishing experiences. There is also a special section devoted to the creative process where original paintings are paired with the preliminary studies and notes leading to the finished pieces. Buy Now

Presents 150 paintings of upland bird hunters, waterfowlers and anglers. Readers will love his detailed depictions of many different breeds of gundogs. Throughout the book are sidebars relating to the general subjects of the paintings gleaned primarily from a lifetime of the artist’s own hunting and fishing experiences. There is also a special section devoted to the creative process where original paintings are paired with the preliminary studies and notes leading to the finished pieces. Buy Now