One of the great wonders of young boys is never realizing how a chain of everyday events can so forcefully change and redirect your own life in years ahead, even into adulthood. For me, raised up in a 1940s small town in the foothills of northern California’s lovely and romantic Coast Range Mountains, it was an outdoor world of cowboy buck hunters that captivated and fascinated me to no end. How could it not?

This was all whiteface cattleand sheep country mixed in with blossoming rows of fruit ranches. Western Stetson hats, high-heeled cowboy boots and pick-up trucks with 30-30s in the rear window gun rack were all part and parcel of that world and mine. The major yearly fall event of these men was a gathering of pick-up trucks and loaded horse trailers lining the town’s one main street, Texas Street. The cowboy riflemen were pulling out to saddle hunt big mule deer in the Rocky Mountains after a three-day drive east. Us kids stood watching from across the street, wishing upon hope we were going, too.

What fantastic adventures would the buck chasers have to tell when they returned? How many thick-antlered bucks would be roped over camping gear in truck beds? Who pulled off that long, running shot at the last moment of a 5-pointer dashing for cover in brush? All we could do is stand watching men climb in their trucks, start their engines and slowly pull away down the main street until they were finally out of sight.

Weeks later when they returned, a second gathering took place as everyone went from truck to truck “oohing and ahhing” at big heads in each truck and listening to tall tales about the wonders of the whole trip. Those cowboy memories are as clear and exciting to me today as they were then, so many long decades ago.

Thankfully, the vagaries of whiskerless youth pass quickly enough, or we’d all vote for them never to end. In 1956 at age 20, I had a small, 10-foot camp trailer and an old GMC Jimmy two-wheel drive truck. My weapon was a lever-action, Savage 99 in 243 Winchester stoked with 100-grain bullets. I meant to chase those old cowboy dreams, even though I didn’t own a horse or trailer to haul one in.

On a map of Idaho, I stuck my finger on the small town of Riggins, set right on the banks of the big, brawling Salmon River. My Idaho Odyssey would begin right there. I was going mule deer hunting, and my “lessons” were also about to begin in ways I could have never imagined.

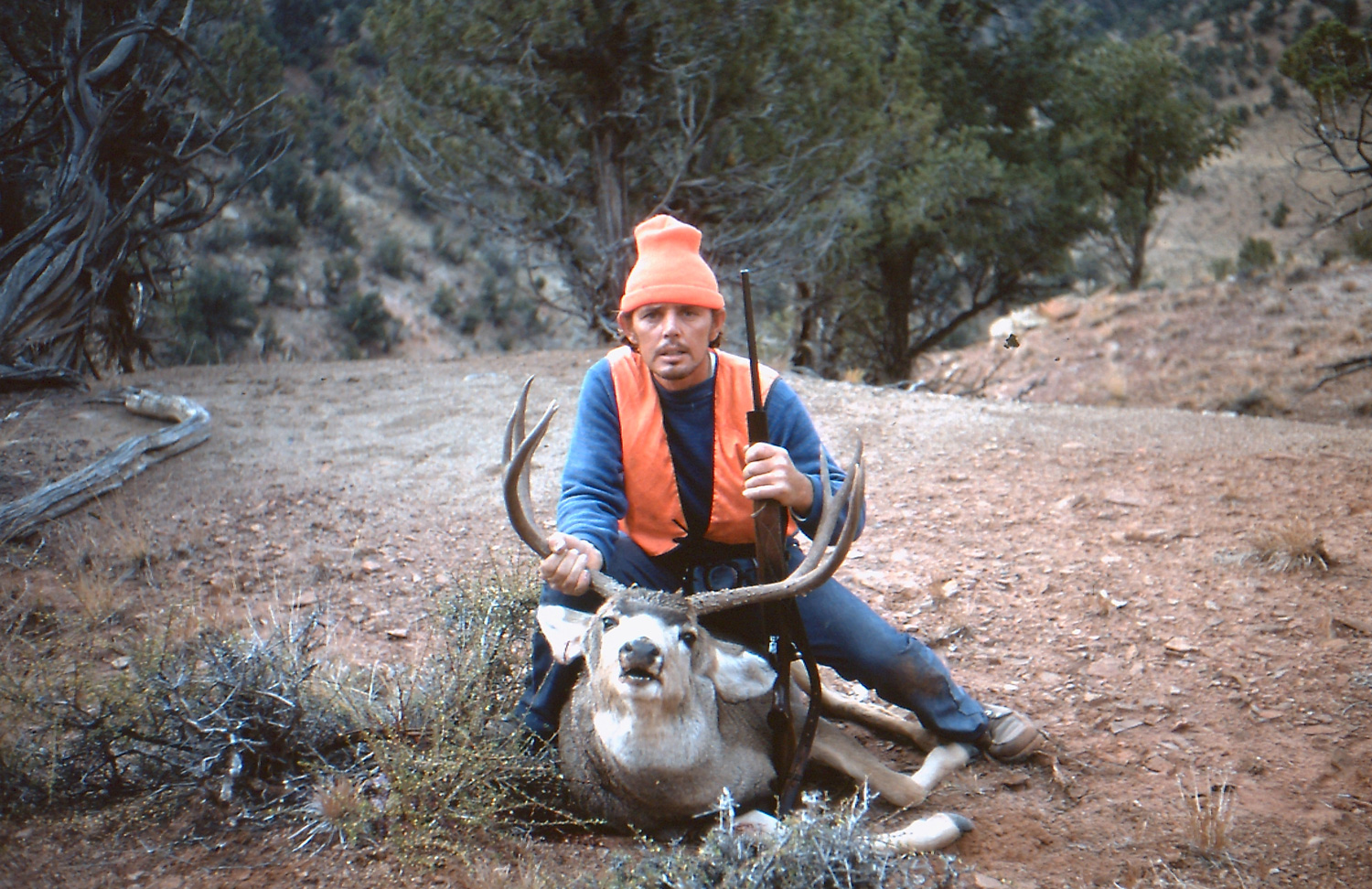

The author’s son, Troy, poses behind a nice 4-pointer taken in Colorado.

Like all Idaho high country, the mountains lining both sides of the Salmon River went steeply straight up and straight down. Any steeper and you’d need ropes. I parked my little trailer in a small camp surrounded by tall pines just behind the hushed hiss of the river. I wondered where to start in a world that all looked pretty much the same. But I was young, tough, had steel in my legs and could climb like a billy goat. I’d take those Idaho mountains head on, hunting right out of camp opening morning.

It took three days of back-busting climbs before I finally hit pay dirt. Halfway to the top, I discovered a series of small, brushy benches scattered with whitened shed antlers everywhere I looked. Big, thick 4- and 5-point mule deer antlers littered the ground. I even found a pair of 5-foot-long elk antlers. I’d unlocked the key to mule deer Valhalla for sure!

For the rest of that week, I climbed and hunted parallel along those benches. I never saw a single fawn, doe or buck. I was stumped. How could that be? Back in camp each evening, I’d sit by a crackling fire pondering my fate, praying to the Red Gods of the Hunt to somehow give me a clue what I was doing wrong. Only silence and the whisper of wind through pines was their answer. The $25 buck tag in my pocket remained unused. Fate and inexperience had dealt me a losing hand—one it seemed I could not win. There were no more aces up my sleeve. Then, something finally did begin to change—the weather. I woke up one morning to grey, ragged clouds hanging low and motionless over the canyons and basins. One day later, snow began falling. Rocky Mountain winter was about to begin.

I decided to abandon my fruitless terrace hunts, climbing instead into the Jimmy and taking on the steep dirt road angling up through Allison Creek Drainage not far from camp. The pattern of new snow made the slippery incline wheel-spinningly slow, the truck dancing side to side laboring higher. Halfway up, worried about getting stuck, I pulled off into a wide spot and shut down. Shouldering the lever gun, I dropped off down the side of the steep canyon and began slowly paralleling.

The air was still and chilly with a hint of more to come. Half an hour in, while stopping to take a break and kneading the feeling back into stiff fingers, I heard the strangest sound I’d ever heard drifting up from the tall timber far below. It started as a low whistle quickly growing into high roars with flute-like notes before tailing off.

At first it sounded like the steam whistle of a mountain logging train running down in the timber out of sight. Then it rose again to another series of high, shrill notes that no machine could ever match. I’d just heard my first bull elk calling out his mating challenge to all who dared come face him. Its beauty, wild and free, made the hair on the back of my neck tingle with electricity. I was in big game country for sure.

Back at the canyon next morning, after another night of intermittent snow, the road was even worse. The old two-wheel drive skidded and danced, losing traction until I finally stopped a bit higher than the previous day. Dropping off the steep sidehill, I began paralleling through brush and timber. Reaching a second canyon, I peeked over the edge downhill. My heart instantly jumped into my throat. There, on a snowy, open sidehill, a herd of mule deer were feeding on greenery through snow with their heads down. I carefully counted every single one, 23 in all, and not one inch of antler among them. Almost as important, I’d seen them first without being seen.

Trying to recover from shock, I happened to glance farther downhill to a line of pines ending the open slope. Something was moving there behind the screen of branches. Lifting the Savage, I peeked through the 4-power scope to a second shocker. Four bucks, all nose to tail, were moving, shadowing the feeders, but staying hidden in cover. I couldn’t believe they’d be so cautious, so secretive. The distance was too great for a shot, so all I could do was sit and watch mesmerized as the deer fed out of sight around the slope of the canyon. But I had learned something of great value: just how careful and cautious big bucks can be.

That night it snowed again. Ten inches of snow now covered the ground, and I knew I’d never get far back up the canyon road. Driving back to the bottom that morning, I lifted the Jimmy’s tailgate and began piling in large rocks for weight, praying for the traction I needed to get higher. This time, the old Jimmy managed to skid and bounce above the previous day’s level. Parking again, I grabbed the lever gun and went down the canyon side parallel hunting, hoping to match yesterday’s amazing discovery.

Morning sun had just lit the canyon rim as I made my way around to another large side canyon. The open slope across from me stood cold and empty and I began to worry I’d missed the only chance I’d get by not trying something more on yesterday’s deer. Sitting to think things over, I drew the Savage close against my cheek, feeling the icy bite of blued steel. A sudden, single, sharp sound like a hardwood club striking a limb came from dark timber directly below me breaking the canyon’s silence. Searching shadowed timber, I saw nothing. But something had to be moving down there.

The timber pocket ended in a steep, narrow shoot that came nearly straight up onto the open sidehill. Finally breaking my gaze into the tangle, I looked again onto the snowy sidehill directly across from me. There, as if by mountain magic, a big, blocky 4-point buck mule deer with wide sweeping antlers was slowly making his way across the open snowfield. How he got there without me seeing him is still a mystery to me even now. One moment the sidehill was empty, the next the big deer was halfway across. I fought off my astonishment slowly bringing the 99 to my shoulder. I was about to begin my mule deer hunting career by downing a buck of a lifetime. The Red Gods of the Hunt, had answered my prayer!

The dark image of the buck on that blazing white snowfield made judging the distance suddenly questionable. Was it 300, 350, 400 yards? I couldn’t be certain. The buck was getting farther away with each step. I had to decide, and now. Figuring for bullet drop, I leveled the scope crosshairs just over that grey back and pressured the trigger. The whiplash crack of the shot echoed off canyon walls, the buck jumping in his tracks and disappearing in two great leaps around the slope of the mountain before I could lever in a second cartridge. Did he jump from my bullet hit?

The author took this massive 4-pointer in Idaho.

It took me a full half hour to work my way over to where the deer had stood when I fired. There was no blood, no cut hair. Only the long, splayed out prints of a running deer. Following the tracks, they went around the slope then turned steeply downhill heading for timber far below. I kept thinking at any moment I’d see my buck lying piled up just yards away. But the farther down canyon I went without seeing him, the more worried I became. Eventually, near bottom, I lost his tracks in a welter of other tracks made by herd deer passing through earlier. Surely, if I’d connected, I should have been wrapping my buck tag around those warty antlers by now.

On the long climb back up, I’d never felt so low and miserable in my entire life. I’d had a great buck tossed into my lap and failed to connect. Reaching the spot where the buck stood when I fired, another shocker hit me. Looking at the distance back to where I’d shot from didn’t look like 300, 350 or 400 yards. No, it looked a lot more like possibly 250 yards at best. The play of angle and light over bright snow on a dark body made my misjudging stunningly poor. Slowly, I began to realize I’d simply overshot that 4-pointer and inexperience played a major hand in it.

I bore the misery of that missed buck every day I hunted until, finally, the last day of season was at hand. The snow-packed road up Allison Creek Drainage had frozen over hard enough that I could bounce and skid my way to the top, dangerous as it was without tire chains. I had no thermal boots or down jacket. Instead, I snapped on rain goloshes and a light wind breaker. I was going mule deer hunting right down to the last legal minute. Shouldering the little Savage, I started off around a level rim above the big canyon. In less than 50 yards, I cut the big, round, fresh tracks of a mountain lion going the same direction I was. Two of us were out deer hunting that morning.

A line of brush rimmed the saddle ahead of me. I hadn’t gone far when I saw two deer running behind it. Through a thin spot, the first deer, a nice 3-pointer, flashed through without stopping. The second, a little forked horn, stopped to see what put his big pal out. Instantly, I drove a 100 grain spitzer bullet in behind his shoulder. The buck whirled and disappeared downhill out of sight. Oh no, I thought, not again.

Pushing quickly to the drop off, I found a big splash of bright red blood on the snow. Twenty yards below, the forked horn lay piled up with his nose buried in snow. I finally had my first mule deer, even if it wasn’t the great buck I’d wanted so badly.

I’ve hunted Idaho many times over the years since that cold, icy morning high on Allison Creek Drainage. And I’ve taken big 4-pointers and even bull elk on hunts with outfitters and guides, in the saddle—the cowboy way of my youth. But these days, decades later, when I sit back and think about the thrill of becoming a bonafide buck hunter, it’s the image of that first big buck slowly traversing a brilliant white snowfield, that always comes to mind. That I fell short, did not dissuade me.

The Red Gods of the Hunt have made my Idaho Odyssey come true many times since. No rifleman can ask for more.