News of Dad’s death was a stunning loss to many of his longtime readers and fans, but a much deeper personal loss to me. My world had been turned topsy-turvy. I knew immediately that I would face profound changes in my life.

With the death of my mother the following July, I became an orphan at 45. Yet I was left with a treasure trove of pleasant memories of many hunts with them in Africa, the U.S., Canada and Mexico.

One of my most vivid early memories was of my first deer, a handsome little Arizona whitetail on Major John Healey’s ranch in the Huachuca Mountains about 70 miles southeast of Tucson. It was 1946, a few months after I had turned 13.

We were on a ridge glassing for deer when Dad spotted a buck partly concealed by brush in the canyon about 100 yards below us. He motioned me to sit in a comfortable shooting position, then whispered: “Hold the crosshairs about three inches below the shoulder and s-q-u-e-e-z-e the trigger.”

I shot and the boom of the .257 Roberts echoed across the canyon. Before I had time to reload, the buck staggered, stood for a moment, then collapsed.

“Well Brad, you got your first buck,’’ Dad said.

And my first case of buck fever. I was so excited that my legs failed me and Dad had to carry my rifle while helping me walk down to the deer.

That same .257, a Mauser 93 fitted with a 3x Weaver scope, was put to good use later when my brother Jerry and I used it to shoot a couple desert mule deer in Sonora, Mexico.

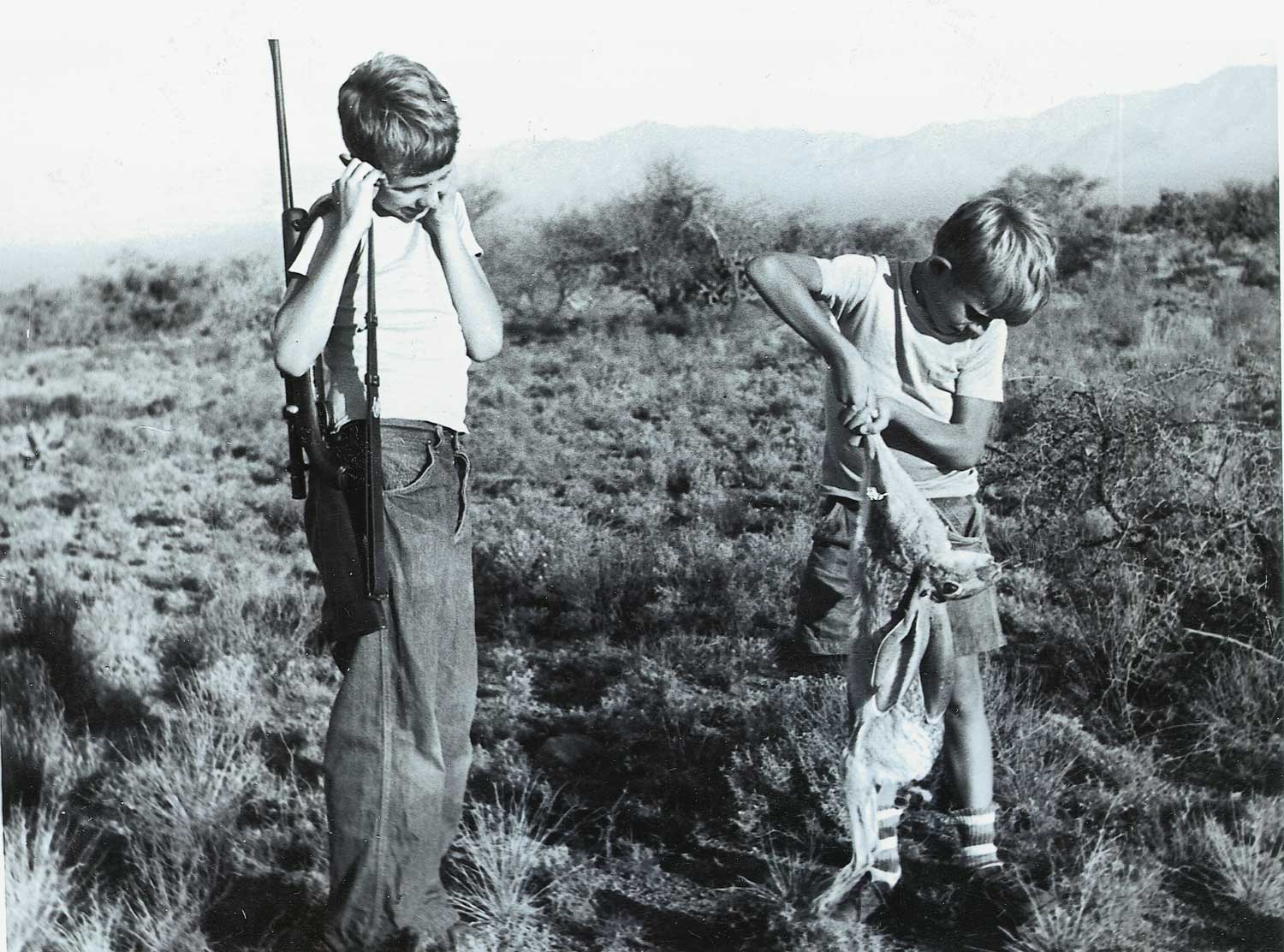

Bradford (right) and brother Jerry with a jackrabbit they bagged in the desert near Tucson (circa 1940).

I recently came across a photo of me at age 5, holding a pair of quail in one hand and what appears to be a kid-size, side-by-side shotgun, no doubt a toy. I don’t know when or exactly where that picture was taken, but I know for certain it was somewhere in the Sonoran Desert not far from our home in Tucson.

I was 5 or possibly a bit older when I began tagging along with Dad and his friend Carroll Lemon on desert hunts for quail and antelope jackrabbits, often in the searing heat of summer.

Those treks (“sashays,” Dad always called them) into the desert were long and tiring for a tender kid, and I always looked forward to returning to our Ford station wagon where Dad or Carroll would reward me with a cold bottle of Coke from the ice chest.

On one of these outings I watched Dad kill a running coyote with one shot, offhand, at more than 200 long paces. The shot was no fluke. In the many years I hunted with him, I can’t recall a single shot that missed.

Dad was also a legendary wingshooter. I first realized this when our family would head to fields near the San Xavier del Bac Mission south of Tucson on hot September afternoons, armed with shotguns and campstools to intercept waves of white-winged doves flying to feed in nearby fields. Dad would limit quickly, scoring on almost every shot, while Mother and my brother Jerry and I would struggle to fill ours.

He was still a deadly shotgunner decades later when his eyes developed cataracts. The fall before he died, three of us in our party missed a pheasant that had flushed 20 yards away. Dad slowly raised his 28-gauge Arizaga side-by-side, said, “Oh hell,” and fired. The rooster folded and fell to the ground with one pellet in the head, 60 paces from where Dad stood. Pure luck? I think not.

Over the next few decades I hunted with Dad and often with both parents in Sonora, Idaho, Wyoming, British Columbia, the Yukon and Zambia, Zimbabwe and Namibia in Africa. All of the hunts were memorable, but the one I think about most often was in the northern wilderness of British Columbia in 1951.

Our party included Vernon Speer and Dr. Elmer Braddock, but Dad and I hunted together most of the time during the month-long expedition. As northern hunts go, this one was quite successful. I took my first wild sheep, a mountain goat and a caribou, and I also learned valuable lessons about ethics and the virtue of patience.

We were a couple of weeks into our hunt and moving our packstring to a new camp when two caribou with magnificent antlers approached, attracted by the scent of one of our mares in heat.

I begged Dad to let me shoot the largest bull, but he forbade it because the caribou season would not open for another day or two, and besides, “to shoot such a dim-witted, sex-addled creature would not be sporting,” he told me. Although I was heartbroken, this was just another reminder that my father was a man of impeccable hunting ethics.

The lesson in patience came at the end of our hunt. We had not seen a caribou for nearly two weeks and there was very little hope of seeing one on this, our last day. A truck from Atlin had already arrived at the end of the road and was waiting to carry our gear and supplies back to Whitehorse from where we would fly home.

While the others packed their gear, Dad suggested that I head to a basin a few miles away where the guide had seen bull caribou at the start of the rut. Hours later, the guide and I returned to camp exhausted but elated. I had shot the granddaddy of all caribou, a bull with massive antlers that would take first place in the Boone & Crockett competition for that year and become the No. 4 mountain caribou at the time.

My patience had been rewarded.

I was 18, no longer a kid, but certainly not an adult. I was a bit rebellious, so that month of father-and-son bonding in the northern wilderness was a combination of good fellowship, outdoor classroom and boot camp.

During long, tedious hours on the trail, we talked of many things, and I began to understand Dad’s deep love for sheep and sheep country, his love for wilderness and his disdain for those who spoil it. I also began to appreciate his passion for the written word. Although I did not realize it at the time, the hours we spent discussing writing shaped my decision later to study journalism and to become an outdoor writer at The Seattle Times.

Almost every day of our 28-day safari in Zambia in 1969 was memorable. Most days I went with Professional Hunter Mike Cameron, while Dad and Mother hunted with PH Ron Kidson. Though we rarely crossed paths, we all met late in the afternoon for a sundowner and a tipple or two to rehash our chases of the day.

One evening I told about a cow elephant that had charged our Toyota Land Cruiser as we headed off the Zambezi Escarpment on a road leading to camp. The enraged animal had come within a few feet of hitting our vehicle.

Dad listened patiently to my account, but said nothing. I knew he was skeptical.

A day or two later, when Mike and I returned to camp from the day’s hunt, Dad greeted me as we drove up.

“Brad, we met your damned cow,” he said. Then he told me about his encounter.

About an hour earlier Dad, Mother and Kidson were on the same road when the cow burst out of a mopani thicket and charged their Land Rover, getting so close that Dad had chambered a cartridge in his .416 Rigby and was ready to fire. Kidson stomped on the accelerator and barely managed to gain ground on the elephant before she stopped and ambled back to her calf.

The saga of the testy cow ended three days later when she attacked four of us while we were on foot scouting for bull elephants on the Zambezi floodplain. It was either the cow or us, so we had little choice but to shoot her.

Jack O’Connor takes young Bradford for a spin in the family’s 1926 Chevy coupe (1934).

By the time I was in my teens, Dad had taught me much of everything I know now about shooting. I started out with a .22 at age 6 or 7, then a .410 a little later, followed by the .257, and still later by handguns and fine shotguns.

However, it was not until 1951 that Dad introduced me to handloading. He thought it would be a good experience for me to load my own .270 ammunition for our hunt in British Columbia. Although I had a youthful fascination for all things that went boom, handloading scared the hell out of me. I regarded it as some sort of devil’s alchemy and that one misstep would blow up a rifle – or worse. But under Dad’s close supervision, I loaded enough cartridges in an afternoon for not only the B.C. hunt, but for several other hunts in the years to follow.

What I learned from Dad that day stuck in a strange way. I committed most of what I learned to rote, and today, more than a half-century later, I can recite details on powder loads, bullet weights and muzzle velocities as easily as I can my date of birth and telephone number.

I recently persuaded a shooting buddy to load some .270 cartridges with Dad’s favorite load of 62 grains of 4831. Big mistake. Neither of us realized that the modern 4831 burns faster than what Dad and I used back in 1951. We didn’t blow up my .270, but the load was so hot we had to tap the expanded cartridge case out of the chamber. Why neither of us consulted a modern reloading manual is beyond me.

Through my father, I met Frank Pachmayr, Bill Ruger, Roy Weatherby, Bill Sukalle and Al Biesen, but I was just a dumb kid who didn’t realize all of these men were giants in the world of guns and hunting.

From the time I was old enough to hunt my first deer, I had access to fine rifles and shotguns, but it took years for Dad’s love for them to rub off on me. Well into my 20s and 30s, I was perfectly content to do most of my upland and waterfowl hunting with a homely but functional 12-gauge Remington 870. But through the years, the more I handled fine guns, the less I hankered to hunt with the old 870. Now, I’m known to swoon shamelessly over the sight of a fine custom rifle or an elegant side-by-side shotgun.

Shortly after Dad died, I took up bicycling, starting with a shockingly expensive road-racing bike built to my measurements at a custom shop near Milan. I was so smitten with this bicycle that within a decade I ordered three more Italian road bikes. The first bike has more than 100,000 miles on its frame. I replaced a front fork damaged in an accident, two sets of wheels, a dozen or so tires and chains, but the frame and the vital components of the drive train are almost as good as new.

What I learned from bikes applies to fine firearms. Fine guns and fine bicycles are built to last and to provide years of flawless service. Dad would not have argued over that.

So today, when I head to the skeet range or to the same brushy draws and stubble fields of northern Idaho or eastern Washington where Dad and I used to hunt pheasants, I leave the old 870 at home. I pack the sweet little 16-gauge Winchester Model 21 Dad gave me when I was a teenager, and even if I don’t see a rooster or fire a shot, at least I’ve spent a day holding something beautiful and savoring the memories of hunting with Dad.

Note: This article originally appeared in the 2010 March/April issue of Sporting Classics magazine.

There’s something about the deer-hunting experience, indefinable yet undeniable, which lends itself to the telling of exciting tales. This book offers abundant examples of the manner in which the quest for whitetails extends beyond the field to the comfort of the fireside. It includes more than 40 sagas which stir the soul, tickle the funny bone, or transport the reader to scenes of grandeur and moments of glory.

There’s something about the deer-hunting experience, indefinable yet undeniable, which lends itself to the telling of exciting tales. This book offers abundant examples of the manner in which the quest for whitetails extends beyond the field to the comfort of the fireside. It includes more than 40 sagas which stir the soul, tickle the funny bone, or transport the reader to scenes of grandeur and moments of glory.

On these pages is a stellar lineup featuring some of the greatest names in American sporting letters. There’s Nobel and Pulitzer prize-winning William Faulkner, the incomparable Robert Ruark in company with his “Old Man,” Archibald Rutledge, perhaps our most prolific teller of whitetail tales, genial Gene Hill, legendary Jack O’Connor, Gordon MacQuarrie and many others. Buy Now