In the last despairing hope of obtaining fresh supplies from Kampala by the road from Uganda to the Upper Nile, I remained at Wadelai, Emin Pasha’s old station, for upward of a month. Lieutenant Cape, R. A., was in command of the station, and together we went into the Shuli country for a few days’ hunting.

We pitched our tents under a large tree about a quarter of a mile from a populous Shuli village, hoping thereby to induce the natives to go out and endeavor to locate game.

Sir Samuel Baker gave the Shulis a splendid reputation as keen and fearless hunters, a reputation which, I regret to say, they entirely failed to live up to. By much baksheesh and promise of more, we did prevail upon sundry gentlemen with more enthusiasm than craft to stroll about the country. But for several days their efforts were not productive of startling results. There certainly was or had been a bull giraffe somewhere in the vicinity, as for four consecutive days we were shown, with no little assumption of acumen, traces varying from two to seven days old.

One elderly optimist, after leading us a weary tramp for hours over sun-baked stones and through ingenious thorns, in the course of which we ascended a hill higher and more inaccessible than the Matterhorn, even went so far as to declare that he had seen the beast. To bear out this statement he summoned by a peculiar whistle another elderly optimist, who emerged from a thorn tree and averred that he had been watching the giraffe since elderly optimist number one had left him in the early morning. He assured us in hissing and as it seemed to me penetrating whispers, that the mythical brute had lain down behind a bush, which he indicated about half a mile away.

With all the creeping and mysterious caution of the climax of a stage villainy we approached the bush and found a sun-baked patch of sand tenanted by a puff-adder. After that we relegated our giraffe to the corner of our memories devoted to fairy tales and the unobtainable lollipops of childhood. At a mere whisper of “twigs” (giraffe) we chanted sweet nothings or gazed into the unfathomable skies.

I am not sure but that we even feared to see one, dreading the horrible carnage that might ensue. At any rate, we refrained from godless hours for a few days, and sipped our morning bohee in gentlemanly ease. Thus it was that one morning at nine o’clock we were sitting in our desk chairs gazing down upon the vast valley of the Nile, which at this hour still showed in all its manifold detail far below. Our camp was on the summit of the ridge that forms the divide between the thankless, bush-clad plains and the stony hills of the Nile Valley, and the endless rolling grass uplands of the Shuli country. Hence our view was not only extensive but of varied interest.

To the east stretched billow upon billow of green downland, ever rising in its unending waves, ’til it smeared the far horizon with a purple streak vaguely suggestive of incalculable distance. Its treeless immensity appealed to our imagination, and we would have given much to penetrate into its as yet undivulged secrets. But station ties kept Cape within a small radius of his base, and the great track between Lake Rudolph and the Nile still remains of the fast-shriveling refuges of the African unknown. A few of even its secrets have, however, already been torn out by the great American explorer, Dr. Donaldson Smith.

To the west lay the great basin of the Nile, a stone-bound, godless waste, scarce redeemed by wide-spreading acacias and the green-streaked courses of innumerable streamlets that oozed from the sun-baked hills and struggled through the dancing heat of the lowlands to join the Nile. The bends of the Nile itself and the small lake above Wadelai showed like silver splashes in the strong focusing of dawn and eve, but during the cruel heat of day wrapped themselves in clinging folds of mist, from out whose ghostly shroud the streaming water blinked blinding flashes at the tyrant sun when the mist parted to the fickle breeze.

When the storm cloud lowers and the sky-rending sheets of flame stagger the welkin to its utmost reach and bring out the turmoil of salient features in bold relief, or when the whole land sobs in content and bursts with responsive green to the warm splashing of the rain, it is a country of surprising beauty. But as it lies for many weary months panting beneath that withering sun, when the grass drifts as brown ash upon the furnace blast, when tree stems split and rocks sear like hot irons the unwary fingers that touch them, then it seems that the curse that blights the African soil has touched the tragic Upper Nile with unsparing hand.

So it was that bright morning when we lazily watched the blue smoke rings from our pipes rise in the viscid air, hang expectant of the breeze, and vanish in the waiting. Early as it was, the mists were banking in the glens, the withered leaves were crinkling together still, the thorn pods burst with ceaseless crackle, the small birds crouched in each shady spot and waited open-mouthed for the far-off evening breeze. The cattle bowed their heads and sought cover of the trees. Even the goats walked staidly or laid down to pensive chewing of what the cool morning hours had brought.

We congratulated ourselves that we had not again been inveigled into that heart-breaking quest of the ephemeral giraffe and swore that nothing would draw us from camp but buffalo, which Cape was particularly anxious to obtain.

A stir ran through the sphinx-like groups of watching Shulis. The feeling of interest spread to us. We glanced up and saw our untiring optimist swinging with giant strides across the hill. Deep in our hearts we cursed him.

After a few moments’ delay, the tall, ebony, white-teethed, grinning Dinka, who, as Cape’s orderly, was self-constituted master of ceremonies, approached with stately salute and informed us that men wished to speak. At the query “Giraffe?” he grinned more comprehensively still, and with majestic wave signified that the Shulis might approach the Presence.

The elderly optimist and an agitated youth, with the curved glass-stick of the Shulis distorting his lower lip, marched up, bowed respectfully, squatted on their hams after deferentially laying down their weapons and, as their custom is, gazed abstractedly into the heavens, waiting for us to speak. As is appropriate on such occasions, we acknowledged their greeting whereat they uttered satisfied grunts and languidly pursued our conversation to its close. Then we turned to them and asked what news they brought.

The elderly optimist, in a manner not unknown at home, proceeded to meander through a sinuous mesh of verbiage, in the course of which he detailed to us his family tree, our pursuit of the giraffe, the last year’s famine, the weather prospects, all of which was sprinkled with vague allusions to buffalo and rhinoceros. At intervals we made efforts to confine him to the desired thread; efforts which only entangled him more inextricably than before.

When he at last emerged from the maze, the agitated youth plunged in and wrapped the matter in superadded ever-cumulating wildness of phrase. At length he too failed. Then their Dinka chaperon, who had listened with unmoved countenance to it all, informed us that they had marked down some buffalo about two hours’ march from camp; that the buffalo were lying down under a tree and would not move during the great heat of the day.

That sounded good enough. We were soon making our preparations for the chase. The lounging flannels were thrown off and old toil-stained pants and thorn-scored gaiters took their place. We donned our heaviest boots for protection against the blistering soil and glanced down the barrels of our rifles for lurking hornets’ nests (a joke occasionally perpetrated by those persistent insects on unsuspecting sportsmen).

I took my beloved double barreled .303 and my grand old barker, the Holland and Holland double barreled hammerless 4-bore, which weighs 26 pounds, and throws with the bursting 14 drams of powder a 4-ounce ball. Cape took his double 8-bore smoothbore and his double .303. Our two guides meanwhile stood motionless as storks, showing no trace of the excitement which stirred within their dust-smeared shell.

When we emerged ready from our tents, they turned like well-trained hounds loosed from the leash and broke into a determined trot. As we swung across the wide sunburnt millet fields, the hushed excited hum that murmured in the village showed the interest that was felt in our success. Buffalo meat, alas! is now a little-known luxury, as that fearful blight, the rinderpest, has swept the Upper Nile as clean as it has swept the whole stretch of Eastern Africa, withering with its pestilential breath the countless myriad mighty beasts that once literally clothed the continent from north to south.

Across the smooth fields we tramped, down the wold-beetling crags of the hill slope, through giant trees shooting far above the tangled undergrowth, across great stony, thirsting wastes, picking our way between miles of unyielding thorn scrub, over rolling hills of withered grass. Blackened beyond recognition by the penetrating ash of burnt weeds, whose stiffened canes tore and spared not, along a water-course wrapped in the soothing shade of wondrous forms of creeping plants and feathered rush we made our way, ’til at last we emerged into a parklike country, where the new grass was sprouting, wakened to life by some fickle storm cloud that had passed the surrounding regions by.

Then, and not ’til then, our guides paused in their weary trot. The heat was beyond belief. The perspiration had ploughed dirty courses through the thick layer of dust and ash that covered us from head to foot. Our clothes hung in more pitiful tatters than ever.

We cursed the fearful sun. It was but a whisper in the great roar of loathing that daily rises from tortured man. What can men in town who write songs in the sun’s praise know of that aching ball of fire that slowly wanders from east to west and leaves a clean-swept track of desolation in its wake. How I, as others, have yearned for the kindly wrapping of a London fog, and dreamed of damp, thawing, wind-bleak streets as havens of sweet content!

The natives told us that we were near the buffalo. They wrapped their goatskins closer ’round their waists, balanced their spears and discreetly dropped behind. We advanced cautiously across an open glade, skirted some thorn bushes and crept step by step toward a wide-spreading tree, which hovered in a chamber in the gorge below. It was underneath this tree that the buffalo were supposed to be lying.

We each took our double .303, and advanced on parallel lines at 20 yards apart. From bush to bush, from tree trunk to tree trunk, we stole. Our natives dropped behind and crouched in the bushes, where they directed our movements with frenzied gestures. Closer and closer we approached, ’til we reached the top of the short gentle slope that led down to the level patch beneath the broad mimosa tree. Behind this patch were some small bushes and a line of dense reeds growing in a small stream; beyond that again was a sharp slope, which led up to the interrupted plateau from which we now gazed down on the level of the watercut.

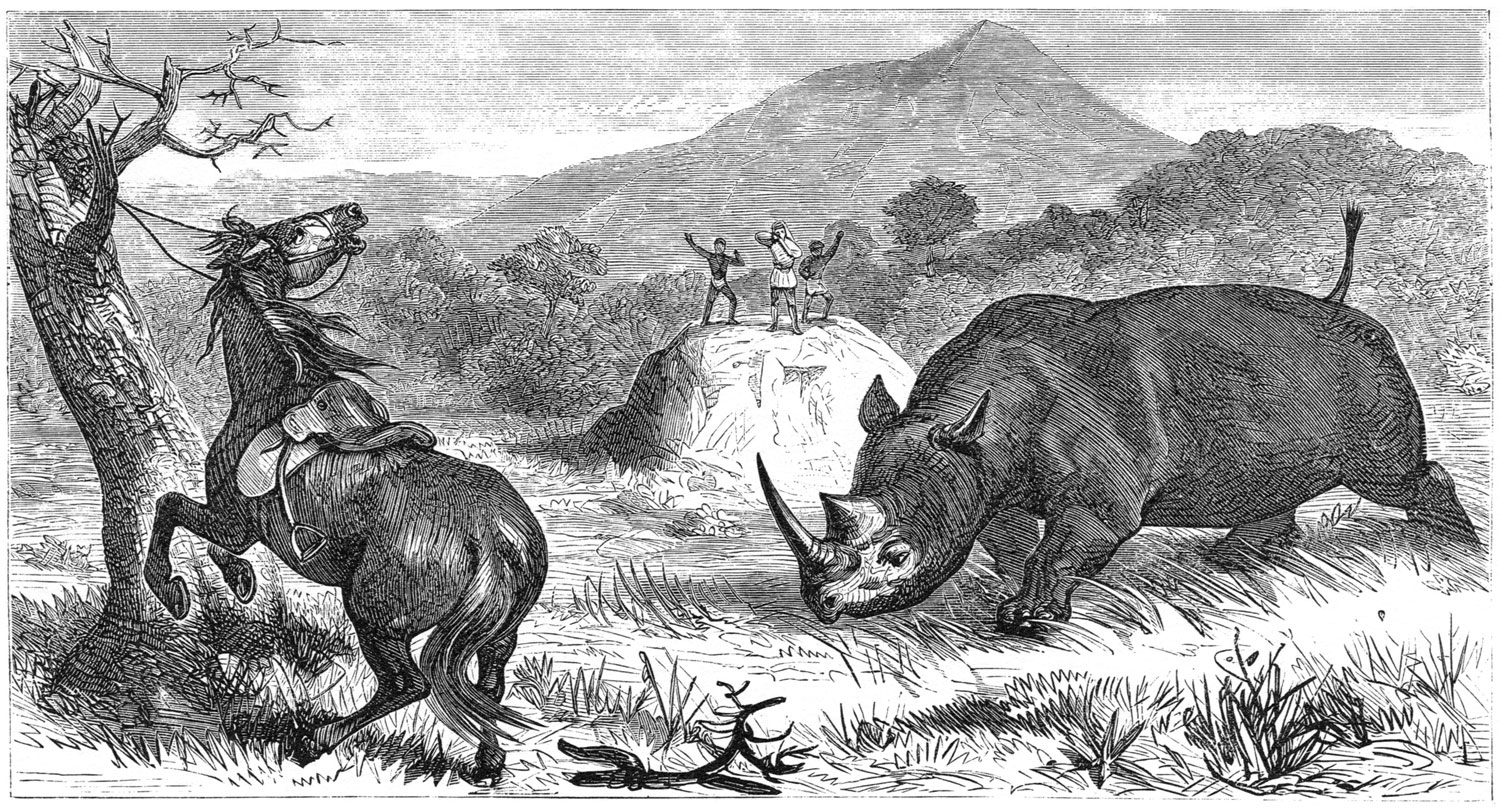

On the ridge we paused, crouching low behind the grass. The sunlight was so dazzling that, in the contrasting shade thrown by the tree, at first we could discern nothing. As my eyes became accustomed to the gloom, I saw at a distance of 40 yards a long convex mass, which at first I took to be an ant hill. I was endeavoring to pick out the detail when a sudden change in the faint breeze chilled the perspiration on my neck. At the same instant the mass moved. A huge beast reared up and showed against the bright light beyond the shade thrown by the tree the heavy outline of an enormous bull rhinoceros.

The overlapping lip, the two horns, the high forehead, the ears alert, the massive chest, the great lumpish neck, stood out in decisive silhouette. He was sitting up on his hams and twitching his nostrils to feel for that alarming scent. Again, the chill on my neck warned me to be quick. As he arose on all fours, I fired the .303 at his shoulder. Cape, from whom the brute had been hidden by a small bush, saw the movement and fired as the animal turned to my shot. Two more rhinoceroses rose at the report, and all three, after a little preliminary pirouetting, during which I gave the bull my second barrel, crashed away through the bushes and into the reeds.

Shrieks as of an engine in its death throes, wild squeals and thundering grunts showed their course. We both rushed down the slope to get clear of the tree. As we reached the bottom, one brute showed for a moment against the sky on the top of the opposite slope and we both fired a double barrel. It was the work of but a moment to dash through the bushes, plunge into the reeds, scramble up the rocky bank of the stream and emerge on the slope.

Cape rushed up to see the course of the one at which he had just fired, while I paused to see if the others had branched off or gone the same way. The ground was too stony to carry much spoor, but, fortunately, there was a little water in the stream and the wet mud from their feet told an easy tale. As I suspected, they had branched; I found the tracks of the one that we had last hit. Thus, we had two wounded, and it behooved us to be careful.

I soon found the tracks of the other two. The strong indentations of their toes showed that they were traveling, and the brightness of the blood splashes showed that one at least had not far to go. After crossing the stream, they had branched at right angles, and were evidently keeping to the bed of the gorge.

Satisfied that they were not in dangerous proximity (I don’t like wounded rhinoceros on my immediate flank), I scrambled up the slope and joined Cape. He was at fault on a very stony piece of ground. Immediately in front of us there was a bare strip of ground, but beyond that endless vistas of close bush just high enough to cover a rhinoceros, and thorny enough to prevent activity in case of a charge. It was a nasty country in which to follow a wounded beast, and especially nasty when there happened to be two.

Meanwhile, my men had joined us. We all cast ’round for spoor to indicate the direction. Suddenly Zowanji, my best shikari (if he might be called a shikari), whistled. We hurried up and found the tracks leading straight into the bush. The brute was walking. He was either sick or feeling “nasty.” Cape took his double 8 and I took my double 4 to be ready for emergencies. As we advanced cautiously through the cover about 20 yards apart, an angry squeal warned us. A rhinoceros pushed through the bushes 30 yards in front, faced us for a moment, then swung round and crashed obliquely away.

Cape’s gun spoke, and the great bullet whistled through the air and “plumped” right royally on the beast’s hide. A protesting grunt greeted the ball, but the brute held on its way without a stagger. By his size we recognized him as the first bull. Throwing prudence to the winds we dashed off in pursuit, vying with one another for the next shot.

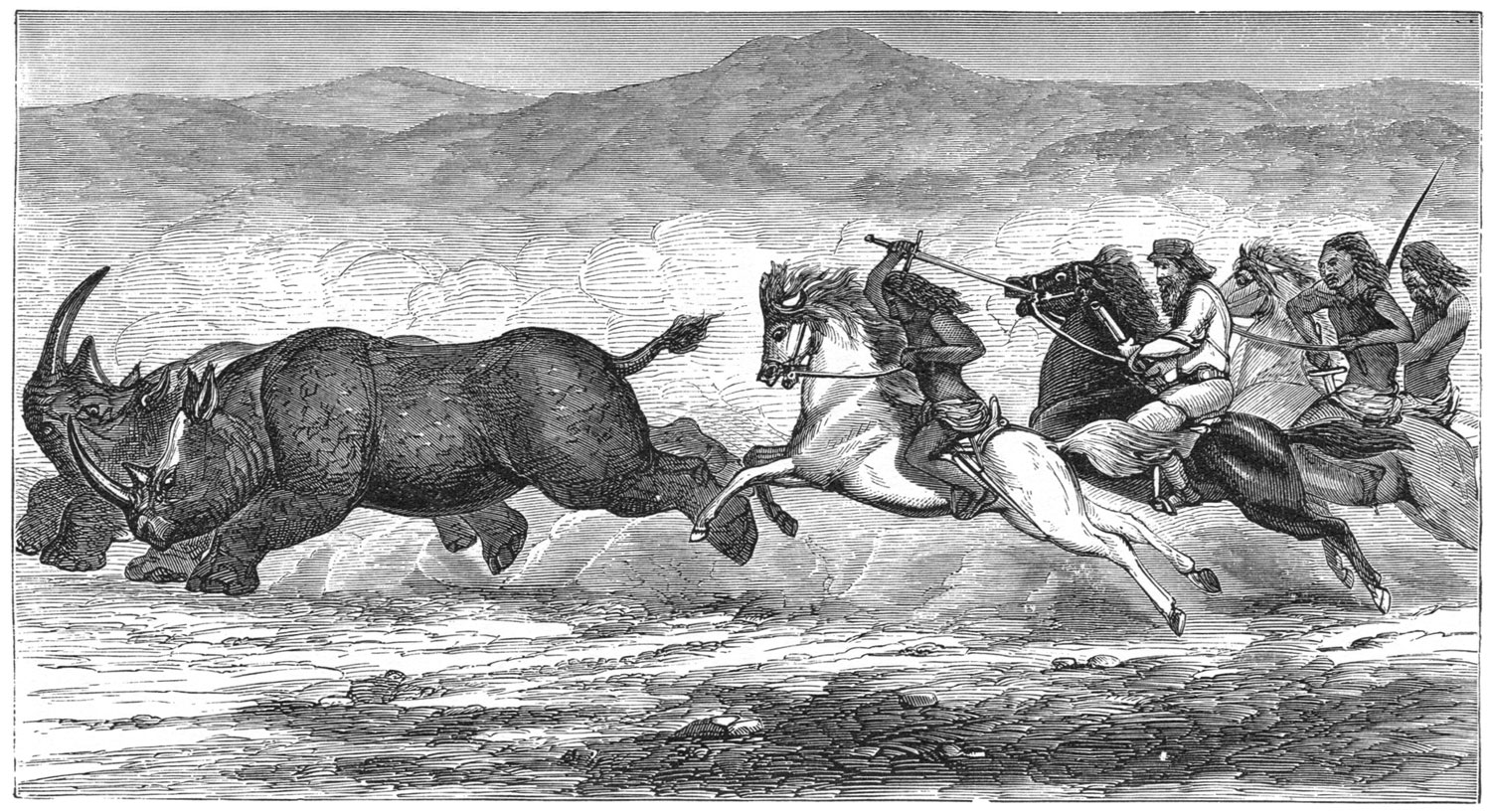

The ground was now soft, and the burst shrubs, torn earth and upturned stones showed plainly the course of the fleeing rhinoceros. The thorns shrieked as they took toll of our rags and buried themselves deep in our flesh to rankle as lasting souvenirs of that great hunt; the sun blazed, the perspiration rolled in great streams, the country danced in the terrific heat, our men lost their fear and became more eager even than we; 4-bores seemed as feathers as the mad procession of fleeing rhino, straining men and sweating natives streamed through that sun-baked waste.

In the fierce zest of that mad chase, we dashed blindly ahead ’til a long whistle called us to our senses. We glanced ’round. The faithful Zowanji, with eyes starting from his head, pointed desperately in front. I gazed hard into the sea of bush and saw nothing but the dancing waves of heat. Then it flashed upon me. Not 15 yards away the evil face of the brute watched us from between two trees. The 8-bore barked, the 4-bore roared, clouds of white smoke wrapped us in, as it seemed, eternal folds, squeals rent the air, and bushes shrieked in their dire distress. The smoke cleared, the evil vision had gone, and again the wild chase began.

Over stone-strewn ridge, through rasping strips of withered grass, along reed-girt watercourse, in and out between fierce clutching thorns, down gentle slopes where the soft earth took sharp impressions of their feet, we kept the terrific pace. The wild dance led us along the inland valleys, up the long gorge and out on to the great terrace that overlooks the Nile.

The last sharp rise had winded the beast. The spoor told us that he was going slow and the dragging of his hind legs showed that the race was almost run. Near the top of the sharp incline another spoor joined the one that we were following. Just below the ridge was a clump of bushes; there the bull had lain down while the other had evidently walked ’round and ’round endeavoring to urge him to fresh efforts.

The blood-flecked foam told of the poor brute’s piteous plight. Knowing that he must now be close, we slackened our pace and peered cautiously over the edge on to the long sweeping slope in front. I soon saw them standing together under a tree surrounded by small bushes. We approached to within 70 yards, when one suddenly turned and faced us. He squealed with rage, stamped the ground, and looked like charging.

It was useless to fire at him thus facing us and, as the other offered a fair broadside shot, I pulled the 4-bore. The bullet went home with a deep thud, and the recipient dashed off at a tremendous pace down the incline. The other turned sharply and received the contents of Cape’s 8-bore. He stumbled off at right angles and stood again under a tree. The end was evidently near. We crept up close and Cape finished the poor beast’s troubles with a shot behind the ear. He dropped like a stone with all four legs underneath him. We went up to him thinking that he was dead. But as Cape passed in front of his nose, with a prodigious effort he rose to his forefeet only, however, to gurgle a last defiance and flop back dead. Satisfied that he was really dead, we drained the last drops of our water bottles, girded up our loins, and sorrowfully cast round for the other spoor.

We were much distressed at having inadvertently wounded the other, and the sun was to exact a fearful atonement for our crime. I had hoped that my last shot would have finished the unfortunate brute’s days. But when we found the spoor, the dark colored blood showed that the ball had entered too far back. After the first burst, he settled down into that long swinging walk that whispers to the tired hunters of endless aching miles.

Elderly optimist slipped quietly away to tell the expectant village of the great store of meat lying waiting for the knife. But the agitated youth was bitten with the fever of the chase and scorned the long miles if they would but bring blood. His face squirmed with excitement and his yellow eyes rolled in ecstasies at the wondrous guns, which could bring down the much-feared rhino.

For a quarter of a mile the track led through long grass, and the quantity of blood made it easy to follow. But after that the rhinoceros had turned down the stony bed of a dry watercourse. We followed this for some time without seeing any place where he could have climbed up the bank. An occasional blood spot showed that we were right, but after a time all trace vanished.

Trusting to luck, we kept to the course a mile farther ’til we came to a patch of sand. The absence of tracks showed that we were at fault. We doubled and hunted both banks. At last I found a spoor. This we followed ’til a small cobweb stowed away in a toeprint showed that the track was not sufficiently recent. Feeling sure that he would try to reach the water, we cast ’round between the Nile and the dry watercourse and eventually picked up his blood tracks.

He had doubled along the donga and had climbed out near where he had entered. Thus, we could only have missed coming closer on to him by about 30 seconds. Disgusted at the loss of time we almost gave him up, as the sun was well-nigh unbearable. But we owed the poor old brute the mournful duty of putting him out of pain, and so we persevered.

Following on his tracks, we soon saw that the country opened out into great rolling slopes with no bush. Only a few trees gave small, isolated spots of cover. With our glasses we could sweep several miles in front, but no signs of the rhino met our longing gaze. Loud and long we cursed that unlucky shot at what we had taken to be the bull, when at the very start he had usurped his line of flight.

The sun beat in giddy waves off the bare ground, the hot puffs of wind crackled in our parched, panting throats, our skin seemed to gape as we could perspire no more and in front stretched out that great sweeping sun-swept waste. Somewhere in that vast tract was the fast-plodding rhino.

Utterly exhausted by the heat, we sat down under a small tree and lit our pipes, hoping to be able to see him moving. Every rolling ridge, every hollow, every tree we searched, but in vain. The grass crackled in the sun and drifted like paper ash at each hot blast of wind. Our rifle barrels seared blisters wherever they touched our flesh. Adjective after adjective we applied to the poor brute. All the time we knew that he was probably trekking, but we would have that rhino if he traveled to the sea.

Our pipes smoked ill-temperedly because of the heat and failed to soothe. Our men spoke in laughing monosyllables, as is the way of natives in disgust. But time was flying and likewise the rhino. Pocketing our pipes, we rose and resolutely stepped out on the last lap, determined that it should end only at his death.

Luckily the ground was soft, so that it was quite easy to keep his spoor. For mile upon mile, we swung along the shadeless waste. After some time, his spoor was joined by that of another, possibly the original third, but more probably one whom he had met, as the whole country teems with rhinoceros. This was discouraging, as the presence of another might induce him to keep on the move.

In grim determination, without ever a word, we relentlessly left the long miles behind, crossed the mail track from the Somerset Nile to Wadelai, and began to descend the last slopes to the level of the Nile. I was leading, Zowanji followed close behind, then Cape and the lengthening tail of natives. A perfectly bare sweep lay before us, with one tree casting a small ring of dark shadow.

I was dashing along, confident that the rhino must be still far ahead when Zowanji again whistled. I could see nothing ’til he pointed out the brute lying quite close to me. The sun beating on his mud-caked hide made it blend so perfectly with the red earth and yellowish grass that I should have walked right up without seeing him.

He sprang to his feet. We both fired. He made a short dash toward us but thought better of it and rushed down a small slope onto a flat bed of short reeds. There he turned again and defied us. Again the heavy guns roared; he spun ’round and ’round several times, staggered, recovered, and dashed off only to stop, however, under the next tree.

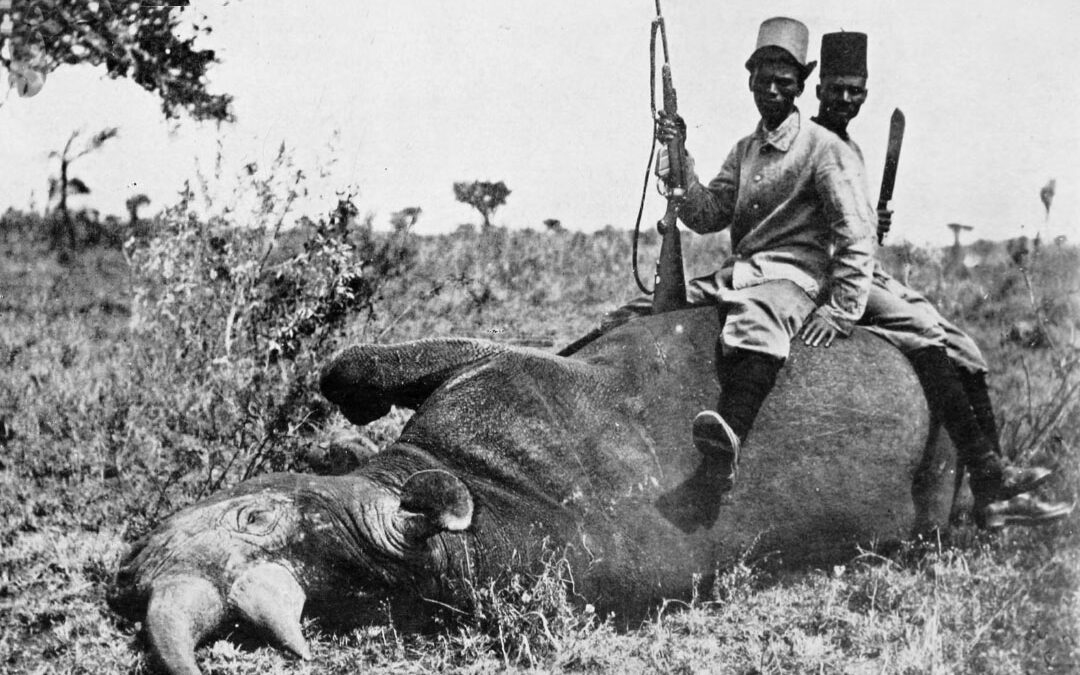

The .303s cracked, and in a wild chorus of thankful yells he toppled over, rose again, spun ’round, and finally subsided into the grass. We went up quite close to finish him. He fought hard to rise and have a last charge, but the little pencil-like bullet again sped on its sad errand, and the game old relic of prehistoric times breathed his last.

We were sad men as we gazed upon his grotesque, misshapen form. Somehow one feels such a blatant upstart in the presence of the pachyderms, when one thinks of the unbroken line that dates back unchanged into the unthinkable ages of the past. It was some small consolation to find that he was a very old rhino, and at least we had in some measure expiated our unintentional crime.

We took off the tender meat that lies on the ribs and, when boiled, makes an excellent substitute for rolled ribs of beef, and, leaving our men to collect the well-earned tidbits such as the liver, heart and tripe, started on our weary tramp home.

The agitated youth wallowed in the blood and thought himself amply repaid when he had carefully secured the long tendons of the back, which are in great request for bowstrings. The return journey without the goad of excitement seemed unending; however, we relieved our sufferings by taking a slight deviation from our previous course, which resulted in the discovery of a small pool containing a 75 percent, solution of greenish mud. It was “no true, no blushful Hippocrene,” yet mud and all slipped down with a smoothness that the jaded palate vainly seeks where are “beaded bubbles winking at the brim.”

A wheeling crowd of vultures showed us our course, and soon the din of excited native-hood rent the peace of the glades. We pushed through the screen of bushes, and at our appearance the fierce babel was stilled. The vast carcass still squatted as we had left it, but no longer in the solitude of the bush. Scores of wild, long-limbed Shulis, all naked as the babe unborn, clustered around and sharpened spears and knives. In their gentlemanly way they had possessed their souls with patience and awaited our permission to begin. We waved assent. Immediately they cast off their proud restraint, yelled, hacked and tore, broke into fierce wrangling, gesticulated, raved, plunged their gaunt arms into the reeking mass, and gave themselves to a wild carnival of gore.

Having given directions as to the removal of the head and feet, we began our weary tramp homeward. The fragrant incense of hot cups of tea, the grateful eddying wreaths of smoke, clung with soft warm embrace around our weary hearts and fanned to bright flame the restful pleasure of battles fought and won. Yet it was sad to think of those strange lives, surviving letters of the almost illegible pages of the past, scattered to all the winds that blow.

Note: This article originally appeared in the September 1902 issue of Outing magazine.