The rugged desert mountains of Pakistan are home to two revered big game animals.

Asia, the largest continent on earth, has fascinated Westerners since the dawn of recorded history and attracted bold adventurers and shikar hunters since Marco Polo reported of his journeys in the Middle Kingdom 750 years ago. My destination was the desert mountains of Pakistan in hopes of harvesting a Blanford urial and Sindh ibex. My intention was to hunt with a rifle while my husband, Ricardo, used his bow.

The lure of hunting in Asia is shrouded in mystic stereotypes and cast presumptions. Just as one conjures images based on the writings of Ruark and Hemingway about the bygone ivory hunters in colonial Africa, so too the shikars from a hundred years ago capture the imagination vivid with texture.

Not many people travel to Pakistan these days, and most who do are men. Understandably so, as there is a fair bit of taboo surrounding travel in this predominately Muslim country, especially as a white, Christian, American woman—thanks media—but really, Pakistan is a safe country to hunt.

“Did you feel safe? Were you nervous as a woman?” Those were common questions during my post-Pakistan interrogation from friends and family.

If you like to push yourself mentally and physically, and at times even out of your comfort zone, Pakistan is a good place to start. Mentally overcoming the preconceived ideas of a woman traveling to Pakistan was all part of the preparation and anticipation. My comfort grew to excitement during my research—speaking to people who had been to the country, and the confidence of our outfitters, Caprinae Safaris. Generally, conflicts happen along the borders of Afghanistan and India; however, we would be hunting in Balochistan in the center of the country, about a two-hour drive north of Karachi.

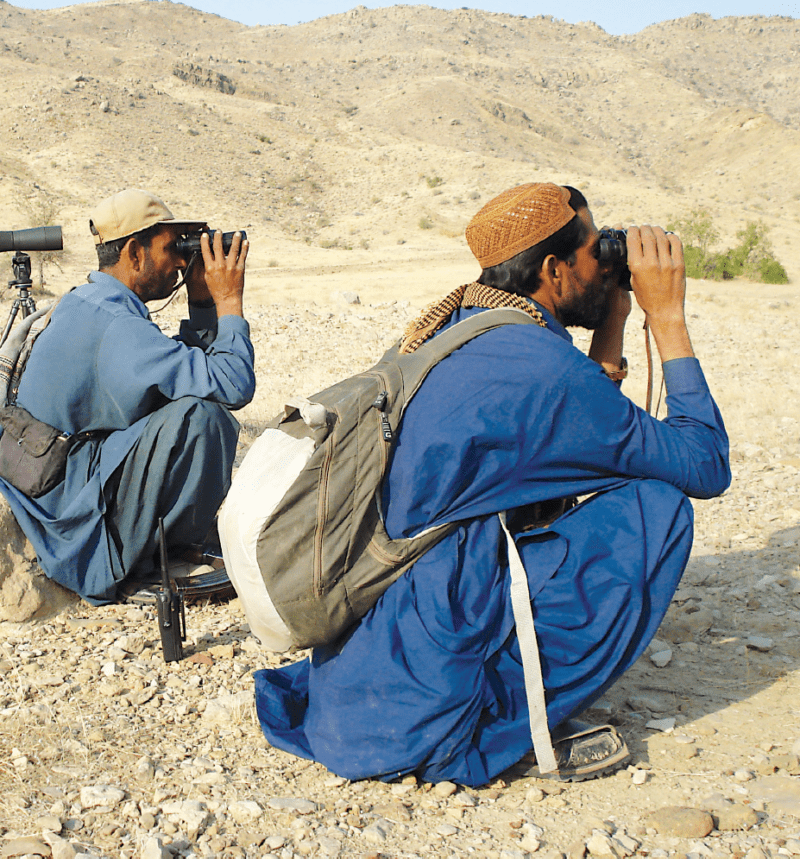

Local tribesmen scan the cliffs for signs of movement. Once animals were spotted, the hunters would begin their arduous trek into high ground.

Prince Bhootani owns and governs the area, and we were staying as his guests. From the comfortable accommodations, we trekked out several hours to the mountains to glass, locate and climb. The rugged, arid, sharp mountains rise from rolling dry plains dotted with well-irrigated fields and mud hut villages.

The remoteness was daunting, yet exciting. At one point I stopped on a jagged tan mountainside peppered with wispy, grayish-green brush, surrounded by the exotic foreignness of the Pakistani dialect, of men in traditional flowing garb and simple sandals, overlooking the dusty depths of barren wilderness below. This dry land cannot sustain much life, I thought, as I watched several men hacking at the sparse brush with their decorated tribal axes and machetes. Their task was to build a makeshift blind tucked into a crevasse on the mountain peak for Ricardo’s bow hunt for a Sindh ibex (Capra aegagrus blythi).

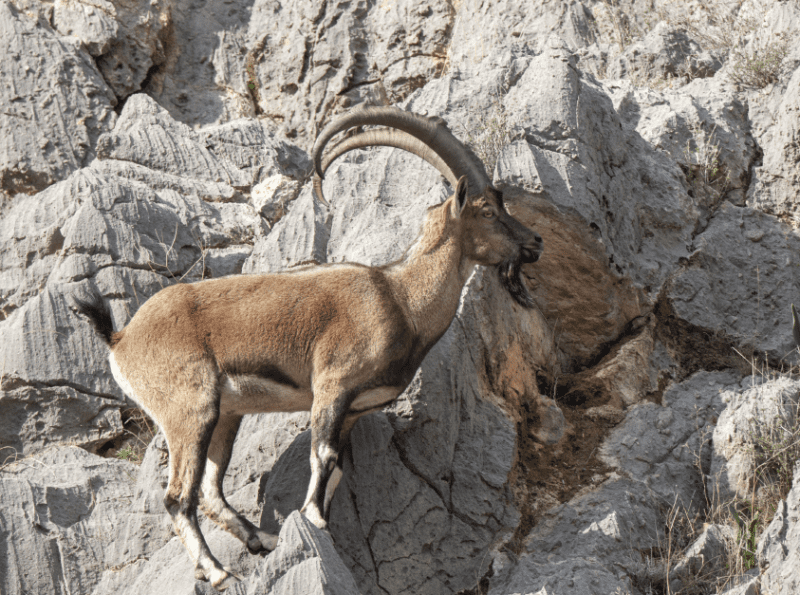

Named after the Sindh Desert of southern Pakistan, the Sindh ibex has a thick-set body and strong limbs terminating in broad cloven hooves. The bearded, mature males are spectacularly handsome, with long scimitar-shaped horns that are strongly keeled in front, then sweep upward and out with the tips diverging. Their almost silver-white bodies are offset by a sooty-grey chest, throat and face.

We were looking for older males, which stand out because of their larger mass and darker face pattern. In adult males, there is also a conspicuous black stripe that runs from the withers down the front of the shoulders and merges with the black chest.

A young ibex pauses while traversing a sheer mountainside.

In the blind later that afternoon, Ricardo and I waited in silent ambush. The local tribesmen knew the patterns of the ibex and had positioned us within bow range along several game trails. Within about an hour, we heard the soft clacking of hooves on the rocks from above and behind us. A small band of ibex appeared, moving slowly and deliberately as they traversed the rock faces, skirting in between boulders and thornbush. One young male made a standing leap of about five feet onto a vertical rock surface, then hopped away in a playful show to join a small herd of other immature billies.

Two handsome billies crested the ridge and casually trotted into range. I saw my husband’s breath change as he whispered to the guide and interpreter while mentally selecting the best of the two animals. Clasping his wrist release to the bow string, Ricardo pulled back fluidly, securing the arrow to the anchor point on his cheek, and within moments released the arrow down the edge of the mountain.

At 47 yards, the arrow entered silently through the vitals, and the ibex flinched and bounded uphill and away from us. Although only a hundred yards away, it took us about 20 minutes to make our way slowly up the sheer cliffs. Some areas provided only a few inches of space to secure our feet or find a handhold as we climbed to where we found him dead.

The Muslim guide punctured the animal’s throat with his small knife, allowing a bit of blood to flow out onto the rocks as he murmured his Halal prayers of thanksgiving, sanctifying the meat for later consumption.

Although I did not kill the ibex, I was more than just a spectator. When my husband and I hunt together, we know that with every step we take in the wilderness and each time we set our sights on an animal, there is much more at hand than the tangible.

There are thoughts and doubts, shared conversations and silent internal monologues, revelations and worries each time we embark into the wilderness. There is always love and death, celebration and sorrow.

We said our own internal prayers as we knelt beside the majestic animal, feeling a very humbling dimension of humanity as a hunter.

Several days of similar setups for Blanford urial, a wild sheep, did not prove as fruitful. We spent long hot hours in brush-covered blinds, lying on handwoven mats of palm leaves, reading Wilbur Smith and occasionally looking up to scan the arid hills for signs of movement or new shapes.

The Blanford urial (Ovis orientalis blanfordi) is a dainty animal, standing only about 30 inches at the withers and weighing less than 90 pounds. The rams have less of a bib than other urial species and no distinctive saddle patch; regardless, they are an impressive desert dweller with both grace and agility to scale these Godforsaken mountains and thrive.

As the days wore on, a number of urials would come and go—ewes and rams that were too small or out of bow range. Shifting my weight as quietly as possible, I could just make out a different ram through the crosshatched acacia branches of the blind. Anxiously, I motioned to the guide and my husband that he was coming in.

We dialed in our binoculars and watched him make his way down off the ridge into the valley. The old ram remained about 200 yards away, not venturing anywhere close to bow range.

Ricardo leaned over and said, “He’s yours, you saw him, you liked him…take him.”

Britt with her Blanford urial taken with a .300 Win. Mag. Blaser customized for the author by Blaser USA.

A bit flustered with the change of plans, I slid into position with the rifle and took the shot. I saw the bullet hit the ground and raise dust behind the ram as he sprinted hard up the mountain. My heart sank and I felt a dreaded pang of disappointment rise up as my throat tightened. The others kept their binoculars on the ram.

“Do you want me to shoot again?” I asked hurriedly.

“No, no—it’s good, just wait,” said Ricardo.

And within a few moments, the ram was down. He was hit cleanly, but instinct and adrenaline forced him to run several hundred yards up the steepest side of the mountain.

Once again, the Halal prayers were said over him, blessing his meat. I placed my hand on the noble Roman nose of my first wild sheep of Asia and felt my own emotions change from a surge of adrenaline to the humbling, sorrowful understanding of what it feels like to take a life. I told the ram that because of him, I was there. I thanked him for giving himself to me, for this experience I would keep in my heart forever.

I am now internally connected to this place, to this animal and to the hunters both past and future who will sit and glass these hills, hoping for the opportunity to collect more than just memories.

Britt visits with Muslim girls from the Dureji Girls’ School.

As our hunt was coming to an end, we organized a trip to deliver our Safari Club International Foundation Blue Bag filled with school supplies to the Dureji Girls’ School. Ricardo and I had brought a year’s worth of supplies for 30 students (pens, pencils, sharpeners, workbooks, scissors, paper, etc.) in addition to backpacks, soccer balls and pumps. I made certain that the interpreters told the girls that we were hunters and that we thanked them for having us in their mountains. I showed them our field photos and they were completely captivated with not only an American woman being in their small school, but also that the woman was hunting, which was considered a men-only activity for their tribe. I highly recommend all hunters to deliver SCIF Blue Bags wherever they go. The experience is priceless.

With 25 superb illustrations, this 288-page book is a must-read for anyone who thrills to hunting big game.

With 25 superb illustrations, this 288-page book is a must-read for anyone who thrills to hunting big game.

From brown bear and Dall’s sheep in Alaska, to elephant and Cape buffalo in Africa, Dwight Van Brunt has hunted much of the world’s great game. In Born a Hunter, his first book, he takes the reader along on more than thirty exciting trips afield. Honest, humorous and edgy, Van Brunt writes in a fashion that goes beyond the too-common where-to-go and how-to-do-it that is so common in outdoor writing. Join him on an exciting chase after a cattle-killing leopard and a grueling hunt for a grand desert bighorn. Share his adventures for Stone’s sheep in the Yukon, desert mule deer in Sonora, and both sable and kudu in Namibia. Look over his shoulder as he hunts bighorn sheep, moose, elk, and deer alone and with his son and daughter. With field photography, and superb illustrations by Jocelyn Russell, Van Brunt has spent a lifetime pondering why he is so drawn to the hunt. His book is a must-read for anyone who shares his passion. Buy Now