A mountain lion peers through glass patio doors, staring intently at a young girl just a few feet away inside the house. Behind the big cat is the family’s dead house cat, freshly killed by the 120-pound mountain lion. Inside, the girl’s mother frantically yells through the glass panes to scare the cougar away, but to no avail. The scene was part of an ad that was seen by millions of Coloradans leading up to one of the nation’s most hotly contested ballot measures last November.

Proposition 127, backed by mostly Washington D.C.-based animal rights groups, sought to ban mountain lion hunting in that state. The ad ends with Dan Prenzlow, former director of Colorado Parks & Wildlife observing, “The cat killed one meal (the house cat) and was eyeing the child as its next prey. That should give every parent chills,” he warns.

Without hunting, opponents of the mountain lion hunt ban argued that the cats would pose an increased risk to residents.

The ad was part of a campaign designed to message to Denver and Boulder mothers specifically and women in general, a demographic opponents of the measure knew were likely to be heavily in favor of the hunting ban.

“We knew the demographics were stacked against us,” says Chris Cox, founder of Washington D.C.-based Cap6 Advisers. For political wonks, his name will be familiar as he served as the long-time legislative architect of the National Rifle Association, with a long list of political victories under his belt.

“Cox has delivered for a long time,” said one Colorado political operative. “I would have handicapped the chances of stopping this measure about the same as a drunk embracing Dry January. This was a significant political upset and to win by 11 percent in Colorado was nothing short of stunning.”

Cox and his team were brought in by a handful of wealthy Colorado ranch owners who were still seething over the ballot measure to introduce wolves that passed in 2020 by less than one percent. It was voters in Denver and Boulder who ultimately decided the wolf referendum, even though the canines were never going to be released in their backyards.

“A coalition of ranchers, sportsmen and supporters of science-based wildlife management was not going to let another measure pass that would usurp the authority of the agency responsible for managing the state’s wildlife,” says Prenzlow, a thought-leader in the effort to defeat the proposition.

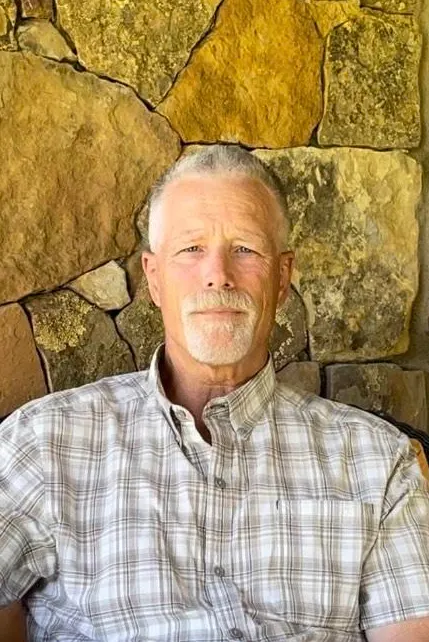

Former Colorado Parks & Wildlife Director Dan Prenzlow.

So-called ballot box biology has been an especially contentious topic across the West in recent years where some of the most bitter wildlife management fights have taken place from wolf introductions to grizzly management. Roughly half of all states have the referendum process, allowing citizens to bypass state legislatures and governors to simply take issues straight to voters. This so-called ‘direct democracy,’ however, is rife with special interest money backing campaigns where facts are often elusive.

A grassroots coalition of sportsmen’s groups led by Coloradans for Responsible Wildlife Management and their Save the Hunt effort marshalled the state’s base of hunters and trappers, holding rallies and producing and distributing ads mostly bolstering the efficacy of Colorado Parks & Wildlife management. CRWM spokesman Dan Gates, looking straight out of central casting for a Jerimiah Johnson remake, became a regular fixture on sporting podcasts and radio shows in Colorado and across the country.

A ballot measure to introduce wolves to Colorado narrowly passed in 2020. (Photo by JEAN-CHRISTOPHE VERHAEGEN)

Gates and many others were successful in convincing sportsmen from across the country that the Colorado fight was an inflection point for all hunters, that the strategy hunting opponents were attempting to execute in Colorado would soon visit other states if not stopped in the Rockies.

That sentiment was echoed by the Washington D.C.-based Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation, and other hunter-funded groups including the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, Safari Club International, Wild Sheep Foundation and more who helped fund the campaign to defeat the measure.

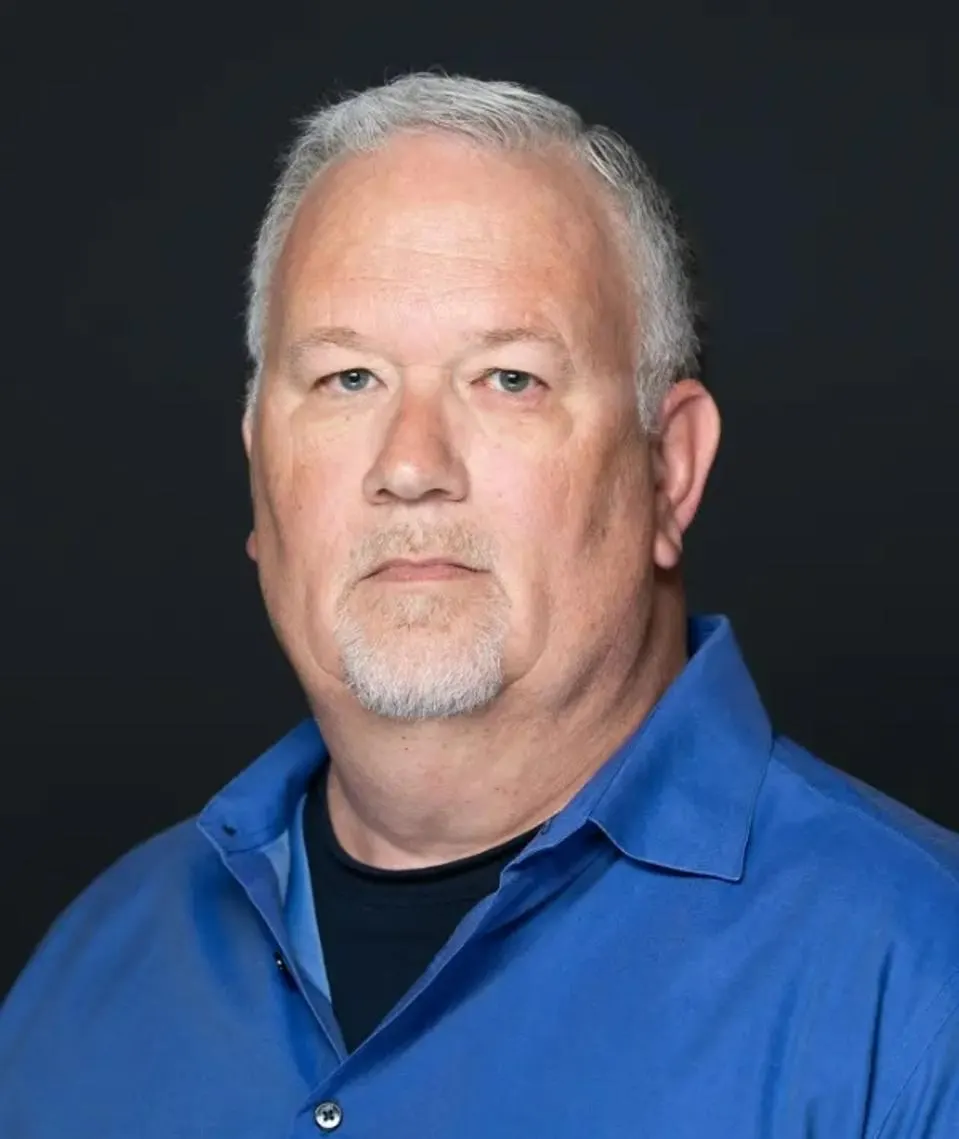

Long time strategist Chris Cox was an architect of the sportsmen’s victory in Colorado.

But hunters only account for seven percent of the population in Colorado, so it was clear to Cox and others that to defeat the measure, they were going to have to target key demographics with messages that resonate—and one of those groups was clearly suburban women. And little motivates more than fear.

Cox brought in veteran Republican pollster Wes Anderson to test commercial spots that highlighted the threat mountain lions can potentially pose to pets and people if populations aren’t managed. Following the defeat of the proposition, Anderson’s team surveyed nearly 1,000 voters to ascertain exactly what messages resonated and with which constituents.

“From our very first survey, it was clear that if the measure were unopposed, the purely emotional message of those seeking to ban mountain lion hunting would prevail,” says Anderson. “Second, their message was beatable if we countered with the inevitable rise of big cat encounters should the ban pass.”

“The path to victory was fighting emotion with emotion,” says Cox. “Championing science-based wildlife management and the important role of Colorado Parks & Wildlife was not, alone, going to defeat the measure.”

Veteran pollster Wes Anderson says warning women about the dangers of not managing mountain lion populations was key to victory in Colorado.

“Messaging against the initiative that focused on the sound science of wildlife management was very helpful for galvanizing hunting and hunter-adjacent households,” says Anderson, “but didn’t demonstrate much reach beyond that community. To impact voters with no direct or familial connection to hunting, we had to make the election about them. The most effective way to do so is to remind them of the very dangerous consequences of failing to manage big cats.”

“The message that a ban on big cat hunting would pose a real danger to kids and pets was clearly the most effective with suburban women,” says Anderson. “In other words, that message did best among the hardest voters for us to persuade—roughly twice as effective as the wildlife management message to that key demographic.”

“While animal rights groups sought to perfect their strategy in Colorado before taking it to other referendum states,” says Cox, “it looks like hunters just might have perfected theirs instead.”

Time will tell as the fight between the two factions is far from over.