He wandered up to the door one day, and with a grunt of half apology and satisfaction dropped down. He had a sort of “I’ve come to stay and to leave you never more” expression. Yellow, gaunt and ungainly, he was a sorry specimen of a hound, and but for the fact that there was no place to bid him begone to, he surely would have gotten the “right about.’’ We made him acquainted with a pan of cornmeal bread, which disappeared with a gulp and a half sigh at the quantity.

“Henry,” said I, “what is it, and what are we going to do with it?”

“Well,” said Henry, “it’s a dog, and a no ’count one at that; but let him stay and we’ll use him to catch hogs.” So we christened him Pomp, and let him stay.

At this time Henry Carter and I were living on a claim in Turnbull Hammock, Florida. We had put up quite a comfortable cabin and had trapped and hunted with varying success all winter.

About a week before Christmas, we made all preparations for an extended tour up country after otters, and we had decided to visit Bull Island, a place much talked of as a wonderful game country and but little visited, as it was decidedly difficult of access.

The day before we started, Henry took Pomp down to Titusville where we went for provisions, and gave him away, for he had proved himself decidedly worthless as a hunting hound and did not appear to know a deer track from a ’possum’s.

How well I remember the morning we started. Henry mounted on a little rat-tailed scrub pony of great endurance, his pommel hung with otter traps, frying pans, a Dutch oven and other jangling camp fixings, while tied on at his back was a sack of oats and blankets. I rode a gray pony of greater size, whose saddle was decorated with traps, bags of provisions and other necessaries.

How well I remember the morning we started. Henry mounted on a little rat-tailed scrub pony of great endurance, his pommel hung with otter traps, frying pans, a Dutch oven and other jangling camp fixings, while tied on at his back was a sack of oats and blankets. I rode a gray pony of greater size, whose saddle was decorated with traps, bags of provisions and other necessaries.

And all was made merry by the mouthings of our hounds. We prided ourselves on our dogs. Bragg, Sherman and Troop cold trail deer hounds with the Birdsong strain strong in their pedigree, and whose music was joy to a hunter’s soul.

We rode straight across through the pine woods to Aurantia Station where we arranged to have another sack of oats left for us by the train from Sanford. From Aurantia Station we rode to Turkey Hammock and there we stopped for our noonday rest. The ride thus far had been through half-submerged pine woods and grass ponds, and the horses were already pretty tired, so we made a good long stop, making coffee and enjoying several pipefuls before starting. However, we at last got under way and, after another two hours’ ride through the worst sort of saw palmetto, we made camp for the night on the edge of a little hammock through which ran a sweet water branch. We gave the horses a good, generous feed of oats, put up our mosquito bars, cut a good supply of wood and made everything ready for the night.

I proposed to Henry that we take a look around the hammock for turkey and deer signs, but after an hour’s walk we didn’t find anything at all interesting, so returned, built up a fire and made a pone of bread and some coffee. After dinner we lit our pipes and somehow got talking about Christmas and what a great day it was for a good dinner, and I remember Henry’s remark: “We’ll have a big buck for our Christmas dinner up on Bull Island,” and then he crawled under his bar and, with a “goodnight,” left me sitting by the fire.

Henry Carter was one of the best fellows in the world, a Georgian by birth and an enthusiastic sportsman, and our idea was, if the ground looked promising, to make a permanent camp up in this island country and trap it thoroughly through the winter. It was a glorious night, and as I sat by the fire I wondered if we were going to have good luck and if there were big bucks up there, and I got a little sleepy and nodded and—what was that? The full notes of a hound on the trail—coming nearer—“Henry,” I called, “get out of that, here comes a hound running—perhaps there’s a deer in front of him”—and we ran out, guns in hands, ready for the fray, just as that mean, no ’count, yellow hound Pomp ran out into the moonlight and opened his mouth in one long howl of welcome. But he didn’t get it—Henry was mad at being waked up by that “low-born hound,” and our other dogs all met him with hair reversed and a series of threatening growls. Still, Pomp didn’t mind, he crept up to the fire and fell asleep as one who has faithfully attained his end.

Next morning found us on the road again, and at night we made our fire on the edge of the Blue Cyprus, across which lay our journey’s end. We didn’t dare tackle the passage at night, as it was dark when we reached the edge, and though the chance of a good dry camp looked anything but inviting, we at last found dry ground enough around an old pine to sleep and make a fire on.

The next day we made the attempt at the cypress swamp and finally rode out on to a good-sized pine island. But, oh, the vexations that lurked among those cypress trees! I remember once seeing Henry wedged in between two trees, his knees tangled up in the trap chains, one hand clutching the bag of oats that was just slipping off, and that restive steed of his receiving in fanciful word pictures a complete history of himself and ancestors.

Well, we found a beautiful place to camp, high and dry, and soon had a lean-to up, wood cut, blankets spread and, in the afternoon of our arrival, put out most of our otter traps. Never had we found so many signs, and on the morning of the following day we put five big dog otter skins on our stretchers. Christmas was two days away. That day we jumped a deer and our hounds ran him out of hearing and did not come back—all but Pomp. He stuck to our horses’ heels.

Next day in the afternoon, the hounds returned starved, lame and miserable. No more hunt in them. That night we supped, as usual, on a pone of cornbread and fried bacon. Henry wanted to know if I knew when Christmas was, and I told him yes, but we didn’t mention dinner. We had 14 otter skins stretched, and that made us feel pretty good, but you can’t eat otter, we needed meat for the dogs, and we could not afford to feed them cornmeal bread. If we did, we’d have to go back soon for more provisions. But up to Christmas morning we hadn’t killed a thing for meat, not a deer could we start—not even a quail could we find—not a ’coon put in an appearance.

We didn’t say much on Christmas Eve about dinner, the big buck or anything else calculated to arouse the appetite. It was a forlorn outlook.

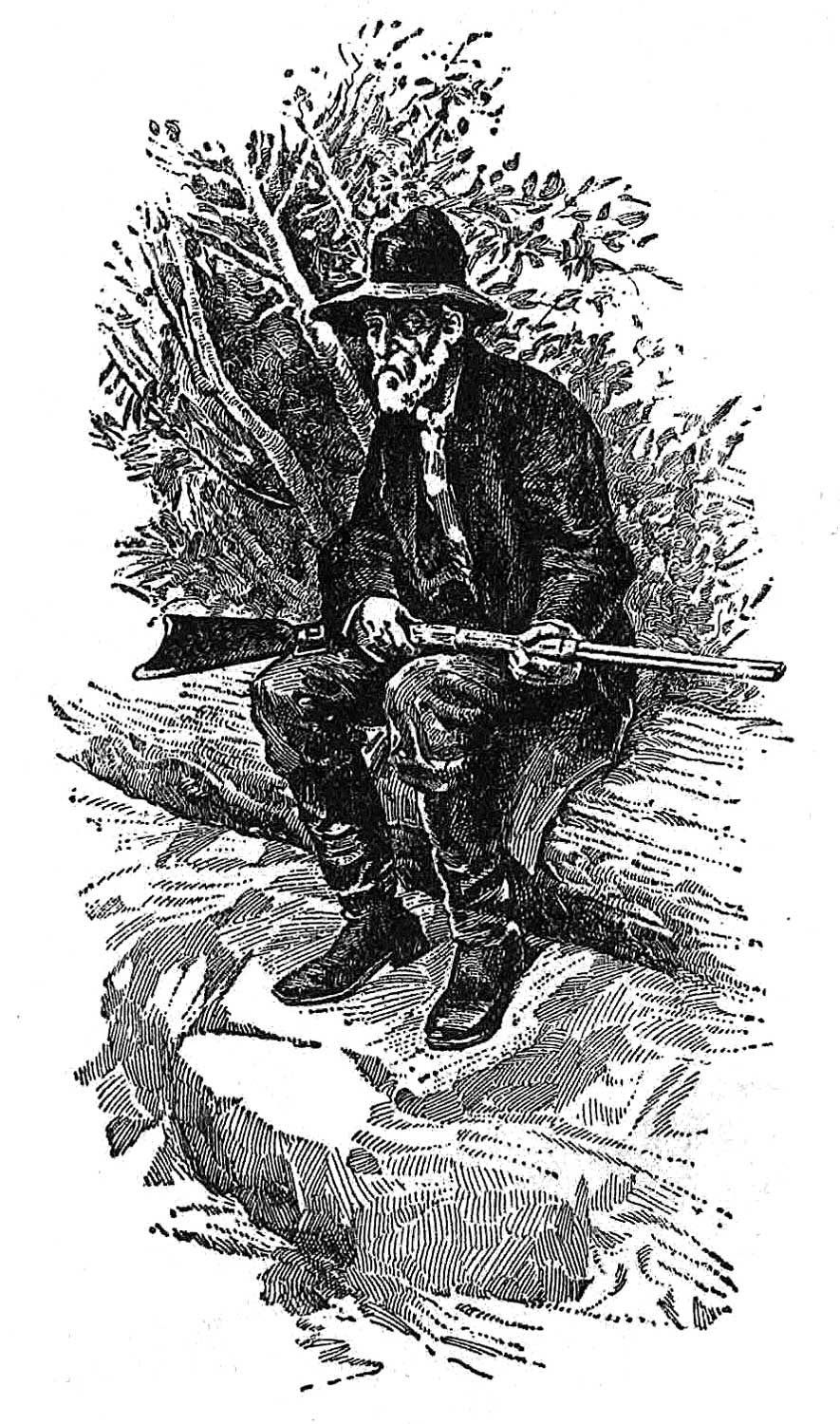

Next morning I wished Henry a merry Christmas, and we both threw what few scraps there were left from breakfast to the “good dogs,’’ abusing Pomp for coming along. As usual, Henry saddled up and started on the rounds of his traps. I started out with Pomp at my heels to get meat for dinner. I didn’t know what to do or which way to turn, the country seemed deserted, not a sign of life. Usually quail could be found, but we hadn’t seen a bird this trip.

Riding listlessly along, I took the direction of a small hammock where I had seen some turkey scratches a few days before, the visions of past Christmas gobblers urging me on. For the first time that morning, I noticed now that Pomp was running ahead of the horse, and really acted as though trying to pick up some cold trail. He appeared full of business, nose close to the ground, slowly working along, and once I heard him grunt his peculiar note of satisfaction, I became quite interested, for it might be a ’coon and that would be something.

I said nothing, but followed slowly on as he picked out the trail across a small grass pond. But just as I rode out on the other side, there, staring me in the face, fresh on the soft sand, the biggest buck track I had ever seen. To say I was interested would be drawing it mild. My heart put in an extra thump, and the whole earth looked more inviting, more like Christmas Day.

But I can’t quicken your pulse with cold pen and ink. You need the actual experience, the sight of that “sorry hound” following each capricious winding of the big deer, as he had fed through the night before. We followed the trail at least two miles to a small clump of palmetto trees and there I felt the end would come. Pomp was quickening his pace, and once or twice he had voiced his mind in a short exultant note, and I could see that he was sure of jumping his game.

Hastily dismounting, I threw the bridle over the horse’s head and, holding it on my arm, faced the trees. Pomp was out of sight, but I heard once or twice his “voice so sweet,” and then the quick-sharp, hair-raising, incessant notes of heavenly music, and I knew the deer had jumped. With a rush, he came out of the thicket, his head like a brush heap bouncing high at every jump like an India-rubber ball. Holding well on his glistering shoulder, I saw at the report the flag come down and on the next jump he stopped, turning his head from side to side, until Pomp’s urgent music started him on.

Jumping on the pony, I sat ready for a ride to head him off, but there was no need. Trotting slowly but majestically, the big buck came straight to where I stood and when within 10 feet of the pony, staggered, fell and died. Pomp got to him about as soon as I did, and we both made merry over him. That no ’count hound coming in for his share, wondering, I suppose, at the new treatment he received.

Well, we got the buck to camp—Pomp and I—and woke Henry up. He was a changed man, the smile froze on his face and stayed there all Christmas Day. We let no grass grow under our feet. Dinner was soon under way, and we sat down to the following menu: Fried backstraps of venison, roast ribs of venison; a beautiful pone of white bread, black coffee and hominy. And Pomp sat at dinner with us—to the exclusion of all other dogs.

After a soothing pipe, we felt at peace with all the world. Strange, but we were never out of meat again, and Pomp became our pride—but he never jumped a deer that I did not think of the old buck at Bull Island, and how he saved our Christmas.

This article originally appeared in the December 1919 issue of Forest and Stream Rod and Gun.