The Benchrest Shooters, a small band of intensely dedicated riflemen, have influenced essentially every aspect of modern riflery.

There are only a few thousand of them at most. When they get together, a crowd of only 60 to 80 is considered a major happening, and their biggest event of the year will be attended by only a few hundred. They call themselves Benchrest Shooters, and the object of their game is simple: firing five, sometimes ten, shots into a single round hole that is no larger than the diameter of the bullet.

This may seem like a pointless enterprise, especially since after decades of trying no one has managed to do it, but along the way, they have changed the face of today’s riflery. The rifle you hunt with, the ammo you use, the scope you sight with, even the way you clean your rifle barrel—all have been greatly influenced by this small, but intensely dedicated, band of riflemen.

Benchrest shooting gets its name from the way rifles are fired from solid benches, usually concrete, with the rifles rested on sandbags (some of these “sandbags,” by the way, eat up most of a thousand-dollar bill). The purpose is to eliminate, as much as possible, errors in holding and aiming. But don’t let anyone tell you bench shooters aren’t keen marksmen. Many are longtime target shooters who have simply graduated to a higher degree of accuracy.

Call it a blending of fine marksmanship, technology and extreme accuracy, with a big dose of competitiveness tossed in to keep the kettle simmering.

An accomplished benchrest shooter will judge within a tenth of an inch the effect crosswinds will have on his bullet’s flight at 100 yards, and aim accordingly. And he or she (never bet against a female bench shooter) will do it dozens of times during the course of a tournament. No other target-shooting game cuts it anywhere near this fine.

The common image of benchrest shooters and the game they play is a bunch of wild-eyed accuracy geeks with Rube Goldberg contraptions that look more like Star Wars laser guns than ordinary rifles. This conception—or misconception—is reinforced from time to time by pictures of these iron monster rifles in various shooting magazines. Usually these rifles are pictured only as curiosities without explaining that they represent a relatively small and steadily diminishing segment of organized benchrest competition, and no longer represent the razor edge of rifle development.

That’s because several years ago some of the wiser heads in the benchrest game realized that despite their ingenuity and fascination, the monster rifles were taking them down a one-way street. Searching for the Holy Grail of pure accuracy was largely a fool’s errand, and if benchrest shooting was to have any lasting purpose, beyond the swapping of ingenious ideas, their rifles would have to be more like—well—like rifles ought to be.

Which is why if you visited a benchrest competition today, say a major competition like the Firearms Industry Super Shoot, you would see scores of rifles that, other than looking like they had been painted by a graffiti artist on a manic high, are not all that different in shape and weight from, say, your Remington or Savage heavy-barreled varmint rifle. Surprise!

This by no means is to imply that we should expect our factory-made hunting rifles to be as accurate as bench rifles, because a winning performance in the Varmint Classes of benchrest rifles will be five, five-shot groups probably averaging about two-tenths of an inch or less!

When I set a new world record for the Light Varmint Class, no rifle and scope could weigh more than 10½ pounds. The average size of my five-shot groups was .1441-inch, which is about 1/8-inch. That was in 2012, and as of this writing my record has already been broken twice, which gives you some perspective of what fine accuracy is all about.

In contrast, of the hundreds of factory and non-benchrest custom rifles I’ve tested over the years, only a skimpy handful have delivered even one group that small, and quite by accident at that. Never mind website chatterboxes who proclaim themselves possessors of hunting rifles that will print half-inch groups “all day long.” Apparently, such claimants have been putting beans in their noses.

The “gold standard” for a really accurate hunting rifle is one that will deliver 100-yard, five-shot groups that measure about one inch on a more or less regular basis. Even among heavy-barreled varmint rifles a true half-incher is a jewel. In either case, extremely good ammo is necessary for fine accuracy, which complicates matters considerably.

The point here, however, is not to compare the rifles we take deer hunting with expensive custom-made benchrest rifles, but to make clear the definitions of accuracy and how rifles you now buy off a dealer’s rack, and the ammo on his shelf, have benefited greatly from rifle developments and improvements first tried and proven by benchrest shooters.

Take for example the effect benchresters have had on scopes. I’ve yet to meet a benchrest shooter who was entirely satisfied with his scope (or anything else for that matter), and they are constantly barraging the scope manufacturers with complaints and suggestions. Scope-makers tend to pay close attention to benchrest shooters, which is why there has been a constant stream of newer and improved target and varmint-type scopes over the past several years, with more and more optics companies getting into the act. New developments and improvements in scopes, proven at the benchrest, filter down to hunting-type scopes, which is readily apparent when you compare the quality of hunting scopes made today with the best of those made a generation ago.

If you’re like thousands of other new rifle-buyers, you practice breaking in a new barrel, an accuracy-enhancing trick originated by benchrest shooters several years ago that has become very much in vogue even among non-benchresters. But by the time such advances have become common practice in the general world of shooting, they may have been rendered obsolete in the esoteric world of benchrest by newer and even better discoveries.

Benchrest competitions are like the laboratory for the rifle-shooting world.

A case in point being the accuracy-improving technique known as pillar-bedding. Benchresters were doing this years ago, but by the time it was adopted by everyday gunsmiths and gunmakers, it had already been abandoned by bench shooters in favor of the even more accurate method of actually epoxy gluing the rifle’s action into the stock. (Don’t try this with your hunting rifle.)

Though it would be unfair to say that benchresters taught bullet-makers how to make accurate bullets, there’s no denying that they picked up on the benchrest concept. Not only liberally applying the term “benchrest” to their most accurate bullets, but borrowing the hollow-point profile of handmade bullets cranked out one at a time by benchrest shooters.

Nowadays there are a dozen or so makers of custom bullets who cater to the benchrest market, and while their jewel-like bullets are suitable only for punching holes in paper or varmints, they set the standard for accuracy that other bullets are measured by. By continuously raising the bar on accuracy, these custom-made benchrest bullets have forced ammo-makers to produce increasingly accurate cartridges, to the benefit of all shooters and hunters.

The best-known fallout from benchrest is, of course, fiberglass stocks. They were developed by bench shooters who wanted a combination of strength, light weight, and stability.

Chet Brown was one of the first makers of fiberglass stocks. Back in the early 1970s, Chet loaned me one of the very first fiberglass stocks to appear in benchrest competition. Painted a bright yellow, it caused quite a sensation, but nearly everyone loved wood back then and most allowed they would rather date the bearded lady at the County Fair than be seen with a fiberglass stock like I was shooting.

This opinion was also shared by hunters when synthetic stocks began appearing on their rifles—but their resistance didn’t last long. Nowadays synthetic stocks of one material or another are about as common as camo T-shirts.

Meanwhile, benchrest shooters have continued to improve on fiberglass with even lighter and stronger materials, such as carbon fiber.

Paradoxically, wood stocks have now returned to the bench game. Creative stock-makers like Terry Leonard have united wood with carbon fiber to produce stocks that are amazingly strong, light, and even rather pretty. I expect this benchrest development will eventually make the leap to hunting rifles, and they will certainly be better looking than today’s “Tupperware” stocks. But don’t expect them to be cheap.

Cruise the gun care departments of a shop or thumb through a shooting gear catalog and you’ll see plenty of products that were incubated in the benchrest hothouse. Popular bore-cleaning chemicals such as Wipe-Out, Montana, Extreme, and Butch’s Bore Shine first showed up on the bench range, with their commercial success coming about only after the critical trials and final acceptance of the benchrest clan.

Bench shooters are notoriously persnickety about what they stick in their barrels and would rather kiss a frog than use an ordinary cleaning rod. Several years ago benchrest shooter John Dewey got fed up with existing rods that he suspected were hurting—even ruining—fine barrels and introduced the line of super-slick Dewey rods widely used by all types of shooters. Other, even more improved rods made of carbon fiber and the polished stainless steel rods I personally favor, were hatched in the benchrest game.

Despite this constantly growing list of rifle improvements we’ve inherited from the benchrest world, if I had to name the most lasting contribution, it would be the revolution in our understanding of accuracy and in the attitudes of makers of guns and ammo.

Benchrest shooters and their rifles established reasonable benchmarks of accuracy and thereby served notice to the gun industry what their customers should expect in the way of accuracy. There was a time, not too long ago, when gunmakers didn’t want to talk much about accuracy, as if it were some sort of immoral subject best kept hidden from inquiring minds. Sure, their advertisements unfailingly described their rifles as being “accurate,” but only in nebulous terms.

A good example of this attitude was an expensive rifle purchased by a friend who could afford such things. Made by a big name manufacturer, it turned out to be dismally inaccurate. Tinkering with it as we might, our 100-yard groups were seldom better than three inches, and usually even worse. So my pal packed it up and returned it to the manufacturer with a sampling of the target groups.

Naturally, he expected the maker to do whatever necessary to improve the rifle, but they simply sent it back with a form letter stating that his rifle fell “within their accuracy specifications.” They never explained, however, what those “specifications” were, and remained smug and untouchable, just as they had for generations past. But that gunmaker couldn’t get away with it these days.

That’s because two organizations—the National Bench Rest Shooting Association (NBRSA) and International Benchrest Shooters (IBS)—sanction tournaments and regularly publish new records plus the performance winners and also-rans of bench matches. (Check out benchrest.com and you’ll see what I mean.) This has put real numbers before the shooting public and flushed gunmakers out of hiding from behind their mysterious “within our specifications” wall. Previously unknown terms such as “sub-minute-of-angle” have become part of our everyday shooting lingo, and now when gunmakers claim to make “accurate” rifles, they had better be ready to back it up.

And some of them actually do, thanks to those funny talking guys with their peculiar-looking rifles.

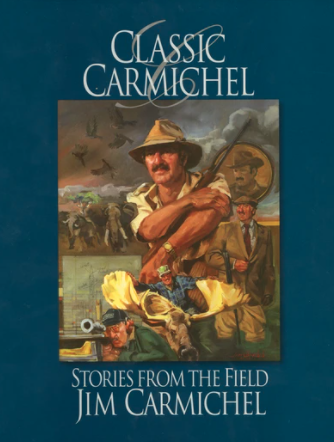

Note: This chapter was excerpted from Jim Carmichel’s book Classic Carmichel, available in the Sporting Classics Store.

Jim Carmichel hunted around the world during his 40 years as Shooting Editor of Outdoor Life magazine. But none of his amazing adventures ever made it into book form —until now.

Jim Carmichel hunted around the world during his 40 years as Shooting Editor of Outdoor Life magazine. But none of his amazing adventures ever made it into book form —until now.

Classic Carmichel features nearly 400 pages of hunting adventures and firearms expertise by Carmichel, widely acknowledged as one of the foremost experts on sporting arms.

Carmichel’s exploits and prowess had no equal during what is arguably the Golden Age of international hunting and shooting. These are not just stories by a well-traveled adventurer—they are pure literature, written with a style and eloquence that deserve inclusion in any collection of great outdoor books and writers. The big 9 x 10½-inch book will feature more than a hundred never-before-published photographs. Buy Now