With only a surplus bullet press in a rented garage, Joyce Hornady began building a company that produces some of the most innovative ammo on today’s market.

A hardy and long-season cultivar, Brussels sprouts continued to thrive on English farms through the hard years of World War II. Much to the chagrin of U.S. servicemen stationed in Britain, these little cabbages became the war-torn island’s ubiquitous vegetable du jour, served in mess halls not only seven days a week but also ladled out at breakfast, lunch, and dinner. At war’s end, many a returning G.I. vowed to never eat one of these mushy globules again.

Selling Brussels sprouts to America’s veterans was, in a sense, the challenge faced by Joyce Hornady when he and his partner, Vernon Speer, decided to begin manufacturing a line of bullets shortly after the war.

“The Harvard Business School,” chuckles his son, Steve Hornady,” should have written up my father’s idea as a classically flawed business premise that worked. Who would think that all those guys, after four years of combat, would want to do more shooting? There’s no way it should have worked at all.”

Nonetheless, it did. America had paid a heavy price during World War II, but in peacetime, our nation was a land of new promise, of better things to come. A growing economy, vacation time for the average worker, and a car in the driveway resulted in not only a new level of prosperity, but also the opportunity for Americans to enjoy the things they loved to do. And for millions, that meant spending time afield or at the range. Before the war, there were some six million hunters in the U.S. By the early 1950s that number had more than doubled.

Growing up hunting and shooting, Joyce Hornady had taken a job as a marksmanship instructor in a National Guard training unit at Nebraska’s Cornhusker Army Ammunition Plant. After the war, the Hornadys stayed in Grand Island and opened a small sporting goods store. Joyce’s passion, however, was in precision accuracy, something he knew could only be achieved with better bullets.

When Speer split off to form his own company (Speer Bullets in Lewiston, Idaho), Joyce found a surplus bullet-assembly press, set up in a rented garage and began producing his own .30-caliber bullet. From the start he had a winner. More than 60 years later his original .30-caliber, ISO-grain Spire Point continues to be one of the company’s best sellers.

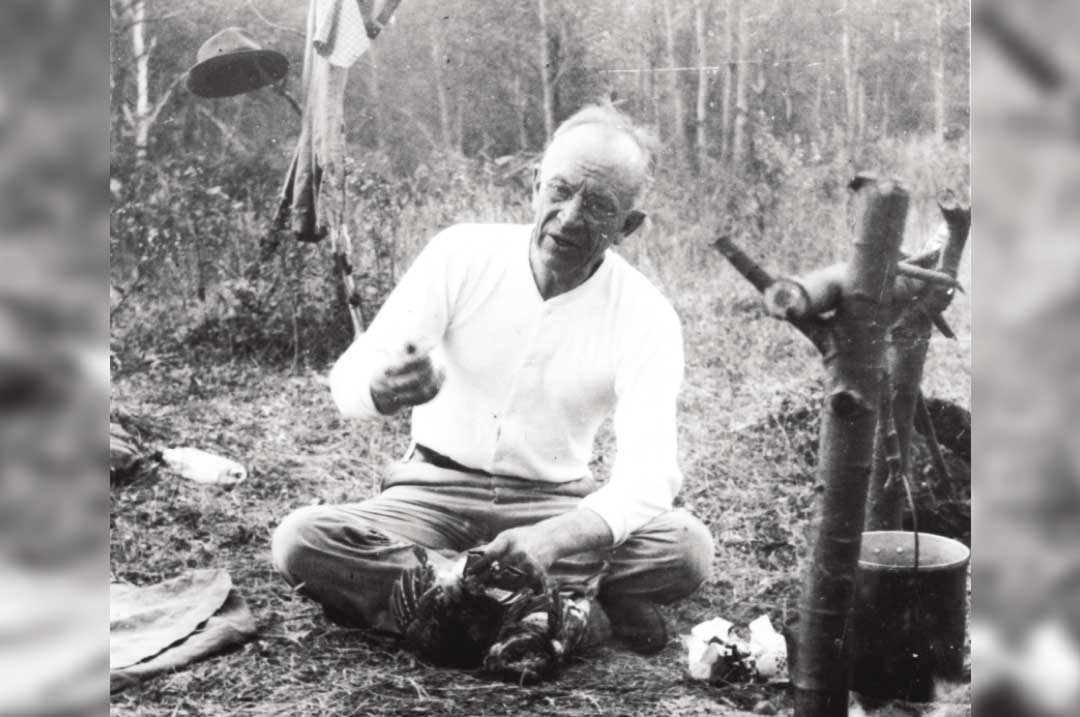

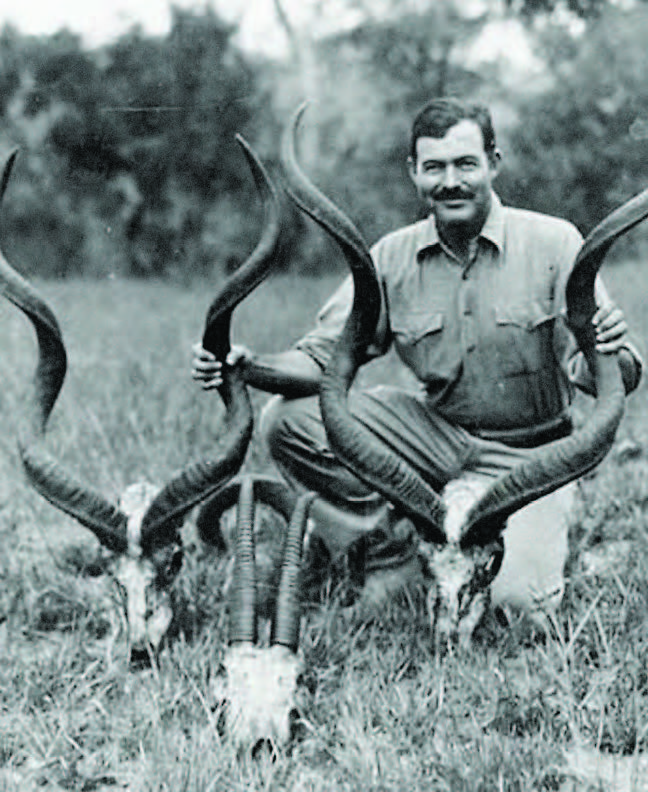

An avid big game hunter, Joyce Hornady ran the company that carries his name for nearly three decades.

With a good start, Hornady committed to building his business, adding more staff and equipment. The severe shortages caused by the Korean conflict looked to cripple the fledgling company, but Joyce quickly shifted production to new areas, notably a government contract for condenser cans. When peace returned, Hornady was able to utilize the material and technology originally used to make the cans to fabricate ultra-thin copper jackets for his line of varmint bullets – a key advance for the company.

By the late ’50s Hornady had started construction on a new factory that would grow to include a 200-yard underground testing facility. Always a hands-on engineer, Joyce had previously driven to the Grand Island Rifle Range to test each individual lot of bullets, whether Nebraska’s sun was shining or not. In the next several decades Hornady continued to expand beyond the bullet business, first with its line of Frontier Ammunition and later with the acquisition of Pacific Tool Company, a manufacturer of reloading equipment.

In the midst of the company’s growing success, tragedy struck. In 1981 Joyce Hornady, along with engineer Edward Heers and customer service manager Jim Garber, were killed when the company plane crashed en route to the SHOT Show in New Orleans. Joyce’s son, Steve, took the helm and continues today as the company’s president.

When I visited with Steve, I asked him what he considered his most important accomplishment over the past 30 years. I expected he might point to the company’s tremendous growth or to a particular Hornady cartridge.

“If anything,” he said, “I fostered a culture in our company that I believe has been the key to our success. We appreciate our employees, and they like coming to work at our factory. That makes a big difference in the effort and the thinking they put into their jobs. We’re all about making great products not just hitting a number at the end of a quarter.

“If we don’t hit our numbers,” Steve smiled, “well, I won’t fire me.”

Being a family-owned company does have its advantages, which aren’t just limited to how the company operates.

“One big reason hunters and shooters like buying from us is because they know we’ve long supported them. We aren’t just shoving it out the door. We give back to the hunting community.”

The Hornadys have given generously to a wide range of hunting and shooting sports organizations, and Steve has long been an industry leader, serving on the boards of the National Shooting Sports Foundation, the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers Institute, and the National Rifle Association.

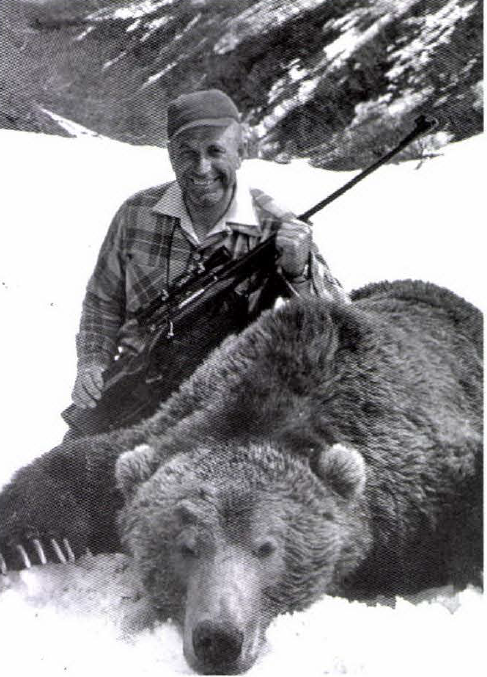

Like his father, Steve grew up hunting and shooting, and for years has pursued wild sheep throughout the world.

“Experience in the field teaches you what works,” Steve noted. “For many years, I hunted sheep with a rifle in .280 Rem. I’ve killed sheep out to 500 yards with that caliber. Over the years, you learn as much about what you need as what you don’t.”

I asked Steve what advice he’d give fellow hunters to help improve their shooting skills.

“Easy,” he replied. “Shoot all the ammo you can possibly afford! We’re like the Frito guys, we’ll make more.

“Seriously, it’s really about learning the fundamentals of good marksmanship and then, practice, practice, practice. Proficiency with a rifle is all about spending time at the range.”

Change in the ammunition business tends to be incremental, typically with revisions and additions to traditional fodder than anything truly out of the box. Not so at Hornady. The introduction of its Leverevolution line, for example, represented a major breakthrough in ammunition designed for lever-action rifles. Safe for use in tubular magazines, these bullets deliver dramatically flatter trajectory, increased velocity, and up to 40 percent more energy than the traditional flat-point loads that lever-action users were historically limited to. It’s ammunition that doesn’t just add to but transforms the capability of a rifle.

The idea behind the Superformance loads came from an employee’s suggestion rather than a formal process.

Hornady’s Superformance ammunition is another a gamechanger. Using specialized powders at normal charge weights, Superformance ammo is 100 to 200 feet per second faster than conventional ammunition. Yet it achieves this added zip without increases in felt recoil, muzzle blast, temperature sensitivity, or loss of accuracy. In essence, it’s getting more from the same.

“The powders we use in Superformance ammunition burn at peak pressure longer,” Steve explained. “It’s like keeping your foot on the accelerator longer. You can pick up speed without going over the red line.”

Whether it’s Leverevolution, Superformance ammunition, or more recent products such as the 17 HMR or 204 Ruger, I asked Steve where these innovative ideas come from.

“Well,” he replied, “we don’t really have a formal process. It really gets back to the company culture I spoke about earlier. Our people are enthusiastic about what they’re doing, and often we create something new when one of them asks, ‘Gee, wouldn’t that be neat?'”

Today, Hornady Manufacturing has more than 300 employees and 100,000 square feet of production space. In a single day, and on just one press, they can produce more bullets than the company’s entire first-year production. Joyce Hornady famously said that, “Accuracy doesn’t come easy.” Nor, I might add, does success. Fortunately for all of us who like to shoot tight groups, the Hornadys have figured out the formula for both.

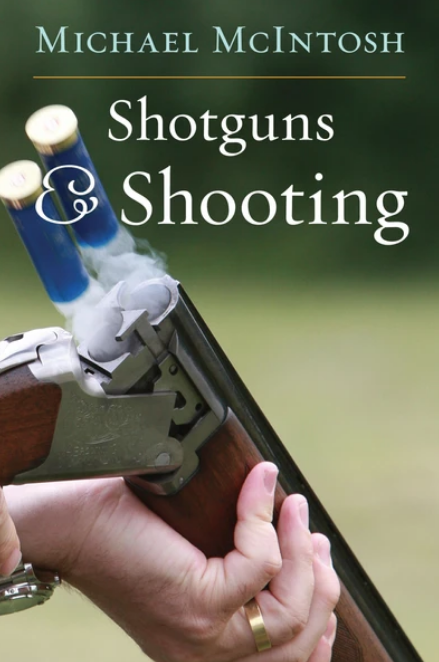

“Truly fine guns are as much works of art as poems, novels, or paintings,” writes acclaimed outdoor writer Michael McIntosh in this classic book. And who better to guide us through the world of fine guns than McIntosh. Here, he captured the whole gun–the gun as a combination of form, fit, and function. Divided into two sections, the first on the art of guns and gunmaking, and the last on the art of shooting, this book is, as McIntosh himself says, “a celebration of the gun.” Indeed, it’s a celebration no lover of fine double guns should miss. Buy Now

“Truly fine guns are as much works of art as poems, novels, or paintings,” writes acclaimed outdoor writer Michael McIntosh in this classic book. And who better to guide us through the world of fine guns than McIntosh. Here, he captured the whole gun–the gun as a combination of form, fit, and function. Divided into two sections, the first on the art of guns and gunmaking, and the last on the art of shooting, this book is, as McIntosh himself says, “a celebration of the gun.” Indeed, it’s a celebration no lover of fine double guns should miss. Buy Now