Night and day they would pursue the huge beast that was threatening the very existence of several villages.

Hope is twenty-three and Faith is two, and they live together, mother and child, in a tiny mud and grass-thatched rondavel a couple of miles from a place called Chakupaleza. The name is a commandment from the Catholic priest who directed the building of the church there to, “Trust that every gift comes from God.” Even though I’ve been there, I can’t tell you exactly where it is, because I don’t know. It is somewhere on the dark side of Zimbabwe.

Not long ago, before Hope and thousands more were settled there by the government, her little spot in the bush was part of an immense “farm” that was lightly tended by a white man, who in the way of his kind, claimed it as his own. Before that, for millennia beyond comprehension, it was the domain of the elephant and the lion and the leopard, that roamed it at will and took from it as they needed.

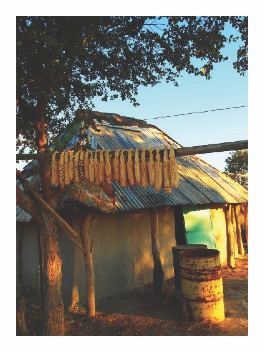

A flimsy stick-and-wire fence rings the tiny hut where Hope and Faith live and separates the bare rust-colored dirt yard from the field of mealies that grow around the little compound. Hope planted the weedy little patch of corn herself with a hoe that she fashioned from a stick and a scrap of rusted metal that her brother-in-law found alongside the dirt track that winds through the bush to the church. Two small, squat mopanes lend sparse shade in the tropic heat. The surrounding land is harsh and thorny, the ground stony, and there is no water short of the well that the missionaries dug behind the church.

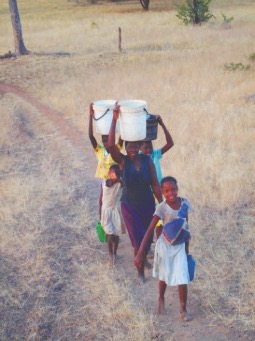

Every morning, before the heat comes, Hope’s sister, Mary, keeps Faith while Hope walks the two miles to the well to fill her empty pail and carry it back on her head so that she and her child can live. Ever since Mary’s husband was killed while trying to chase the big elephant from the field, Hope and Mary tend the field by themselves, taking turns with Faith. In the evening Mary retraces the route to the well and returns to her own hut on the far side of the hill, leaving Hope and Faith alone.

The little field of corn provides the only source of nutrition for the three of them, and if it is stolen or if it fails they will die a slow, painful death of starvation. There are no jobs in the bush. There is no government safety net. They walk the razor-thin edge of starvation all the time. There is no game. Only the elephants. The last game of any other kind disappeared years ago, as the snares of hungry people took their horrific toll. Not so much as a hare or duiker is to be seen. Their friends and family would help them if they could, but they are hard pressed to secure their own survival.

Native women and children return with water from a nearby well to their rondaevals, crudely fashioned from mud and thatch. Many families plant small plots of maize, which are easy pickings for hungry elephants. Woe to the luckless native busily tilling his crop who suddenly finds himself surrounded by the huge beasts.

This story begins on a searing hot afternoon near Victoria Falls. The temperature hovered near 100 degrees, and I was sleeping away the midday heat in Gordon Stark’s Nhoro Safaris camp on the bank of the Zambezi, where he sometimes allows vagrant writers and other undesirables to crash. The ten-foot stone walls and high thatched-grass roof of the hut provided a small temporary refuge.

Gordon’s sun-creased face suddenly appeared in the doorway.

“Want to shoot an elephant?”

“Not really. Why?”

“Because we’re going to shoot one if we can. Tonight, or in the morning.”

“What’s up?”

“I just got word from the local chief that there is a big tusker raiding the fields a few hours from here, and the tribal council has put out a hit on the old bastard,” Gordon said. “He’s already killed once and when an elephant realizes how easy it is to kill a human, it often becomes a habit.”

The elephants come out of the parks to steal corn and when the locals try to chase them out of the fields, the elephants are annoyed,” he added. “Of course, it’s not good to annoy an elephant, but the locals have no choice. Then the elephants learn to solve the problem in the most expeditious way possible.

“This big-toothed old guy picked up a local with his trunk and beat the poor fellow on the ground until he stopped moving, then put him down and carefully, with malice aforethought, stepped on his head for good measure. We have a license, so it’s up to us to solve the problem before he does it again.

“So, do you want to shoot an elephant?”

We left camp just past 1 a.m. in the absolute black of a moonless African night. Gordon and Ezekiel, the chief, rode in the front with the driver. A couple of trackers, the government game scout and I crouched in the back, hunkered against the rear of the cab for warmth. One of the trackers was of the Ndebele tribe and spoke no English. Jefferson, who spoke impeccable self-taught English, was a Shona. Along the way, Jefferson spoke of crossing the Inyantue River and the Lukosy, but I don’t know. From my position, all that I can say for certain is that we were beneath the Southern Cross.

We rolled into the yard of the little stone church just before dawn, stretched to work the kinks out and set out single file down a small a ridge that ran between two deep valleys, picking up a local guide en route. He knew nothing more than what we’d heard but guided us to a small group of huts where one of the chief’s cousins lived. Unfortunately, the news was not good. Nobody had seen the elephants or heard any new reports during the night.

“What’s next, Bwana?”

“We’ll send out some runners to look around,” said Gordon. “Just relax. It looks like we’ve got a wait on our hands. If any of the locals sees elephants, they’ll beat a drum, if they have one. If not, they’ll bang on whatever they have until someone comes to check it out. We’ve got quite a network out. If anybody sees him within ten miles of here, we’ll get word of it. It may be tonight, though.”

We propped on elbows in the slim shade of a small mopane and settled in to wait. The day stretched interminably as runner after runner returned without news while we passed the time as best we could. Politics, sports, women, all the usual topics were thoroughly flogged. Weather. The heat. And elephants. The subject always returned to elephants. We ate and drank and whittled sticks and doodled in the dirt while African insects, as of yet unnamed, ran strafing run after run. Rifles were checked and re-checked, and cartridges inspected, one by one. But no news came. We napped in the sparse shade. Still no news.

Finally, the burnt-orange sun fell, and the evening filled with the sounds of the African twilight. Somewhere in the valley cowbells thud-clanked as some hardy soul sang a poultice against the night and drove his charges along. Children laughed in the distance and the crisp whacking of a wood-chopper echoed from the far ridge.

When the last light from the thin, reclining moon faded, we spread a canvas tarp to lie on, wrapped in a light cotton blanket and tried to sleep.

Gordon had warned, “You should sleep if you can. It’s likely to be a hard night. We’ll probably get word of them, if they haven’t spooked and gone back into the park. Somehow they know that we won’t follow them across the park boundary. The parks are ‘cash cows,’ and we can’t go in, even for a man-killer. If we don’t hear anything tonight, we’ll move a few miles and wait again.”

Around 11 o’clock we were awakened by an excited chatter that ran through the group of huts. A runner had come from a couple of miles away to report that someone had heard banging in the direction of the place where the big elephant had killed.

Gordon went to check out the report and returned. “We’re going after him. Load your 416, put it on safety and watch where it’s pointing. If we can safely shoot in the dark, we will. If not, we’ll try to pick up his trail where he leaves the field in the morning and hope he stops to feed or rest in the middle of the day. If he does, we may get a shot. If he doesn’t, we won’t catch up to him.”

Gordon’s face hardened, “Are you sure you’re up to this? This isn’t going to be easy. I don’t mean to be insulting, but you’re not a young man, and you don’t have to do this. Are you sure?”

“I’m sure.”

“Then get your boots on, we need to move fast!”

Two or three miles into the darkness we, too, heard the rhythmic banging, barely discernable at first, carried softly on the night, then growing louder as we closed the distance. Visibility was nearly nonexistent, limited to the black frame of Gordon directly in front of me and vague shuffling shapes ahead of him.

We followed a worn footpath through thick bush, crossed a dry creekbed and entered a small cornfield. The head-high stalks further limited visibility and I was trying to make out the treeline, when Gordon stopped with such suddenness that I ran into him, nearly causing both of us to fall. Despite the collision, no one spoke, and it seemed that all were frozen in place, when I saw the reason for the sudden stop.

The enormous shape of an elephant’s head was outlined in starlight no more than 20 yards ahead. By squinting, I could make out another, much smaller form slightly to the right of the first.

Not good! A cow and calf were standing directly in our path, and I suddenly understood the meaning of the term “pucker factor!” Her trunk rose and tested the wind for several seconds, and then she and the calf were simply gone. There was no sound. No perceptible motion. There was only naked, starry sky in the spot where they’d stood. One-by-one we slowly exhaled.

By skirting the downwind side of the field, we found another half-dozen elephants and when we closed a bit on the source of the banging, we almost had another pile-up.

Jefferson was leading and had seen three elephants about 30 yards out in the field. When the wind shifted slightly, we realized that we were close enough on the downwind side to smell the pungent odor of dung. One of them was clearly larger than the other two, but not so much as the difference between the cow and calf.

Gordon and Jefferson crept forward as the others fell back. Gordon tugged my jacket for me to follow, but we had only closed about another ten steps when the two men stopped, watched for what seemed an eternity, then began easing cross-footed backwards between the stalks. The others followed, and when we had put some distance between ourselves and the elephants, Gordon whispered, “It was the big bull, alright, but he had two smaller askaris with him.

“We might have taken a shot, but it was just too dangerous. If the shot were not good, or if the askaris rushed our light, we would have had a bad time. Probably they wouldn’t, but with elephants you never know. And these are bad elephants.”

As soon as we were free of the three bulls, we continued to follow the downwind side of the field until we closed in on the source of the banging. Illuminated in the narrow beam of the flashlight, we could see a young woman, squatting in the doorway of a small mud hut, banging on a pan and mumbling unintelligibly.

“What is she saying?”

Jefferson answered, “She’s praying.”

The young woman lurched when Ezekiel’s voice came from the darkness, but she didn’t speak. Her face, like ours, was caked with the ever-present dust. Our small light revealed where her tears had run their course before puddling into small dark spots on the earthen floor. She held a large wooden spoon limply in her right hand and a small tin pan in her left. A small girl in a dirty blue and yellow dress lay in the dust a few feet away in the center of the room. She didn’t seem to be afraid, but her dark eyes seemed oddly blank as if she were somehow detached from the goings on around her.

The chief said that the woman’s name was Hope, and when he told her that we would stay until dawn, she calmed, and we left her and re-crossed the hard-packed earthen yard where we sat quietly in a line along the fence and waited for daylight while she and her child slept.

At dawn, Gordon sent out the two trackers who circled the field and picked up the trail where the three bulls had left the field before dawn. One track was big, well over 20 inches, slick-heeled and deeply riveted. The other two were smaller. We followed their trail from the field through long uphill miles of thick jesse, then over a steep rocky ridge and down into a long valley of ten-foot elephant grass where visibility was no more than an arm’s length. An elephant ten yards away would have been invisible.

As we inched along, Gordon and I walked in the trackers’ wake with rifles at port arms, constantly searching for some slight movement that would give away a charge. After a couple of hours, the trail broke out of the grass and onto a sandy creekbed that led us to a small waterhole barely three feet wide.

The three fugitives had stopped at the spring to drink, and since all of the sign indicated they were now well ahead of us, and the sun was lowering, we decided to sleep there on the ground for the night.

Within a few minutes slender dark forms began to emerge from the surrounding bush. Our presence was apparently well known in the area. Greetings were exchanged, and mealies were offered. We thanked them and boiled the hard dry cobs in a small black iron pot and choked down the meager fare before we went to sleep. We were too tired to talk. As they left, one grizzled, gray-bearded old man in dirty khaki shorts, stopped, and in perfect English, said “Thank you for coming to kill the elephant.”

We trailed the herd until about noon the next day, through hilly bush that turned to green mopane forest and into another deep valley filled with elephant grass. In the center was a rock spire about 40 feet high, and Gordon told the Ndebele tracker to climb it and take a look. The tracker climbed as far as he could, then glanced down and simply shook his head.

Gordon looked back and said, “We’re done. The ridge in front of us is the park boundary and if we cross it, we’re in more danger than the elephant.”

With that, we turned our backs on the elephants and began the long walk home. No one spoke.

This story isn’t unique. It’s repeated on a daily basis. Only the names change. It always ends poorly for someone, either the people or the elephant. No one talks about what happens here, because talking is dangerous in Zimbabwe. The people fear their own. And they fear repercussions from people who live far away and who know nothing but what they read and what they imagine. People who turn a deaf ear to the truth because they don’t want their prejudices contaminated by facts. People who condemn them for simply trying to survive.

Gordon was right. I am an old man. And with age I have become somewhat cynical. But I know how any conflict between man and beast inevitably ends. How it must end. How history dictates that it always ends. History will record many villains in the story of the passing of the elephants. It will include commercial ivory poachers, corrupt politicians, unconcerned and incompetent wildlife officials, and the government that orchestrated this unholy mess. But there are no villains in this story. Not the people nor the hunters nor the elephant. There is no moral here. It’s just a simple story of a couple of days in Africa. As in all of the African bush, it is amoral. It simply is what it is.

I have known the elephant. I have stood in his footprints and trembled in his shadow. I feel for the people and I grieve for Africa. And when he is gone, I will grieve for the wild African elephant in a way that the fraudulent “animal rightists” cannot even begin to understand. They do not know the elephant and never will.

Africa will indeed be the poorer when the elephant is gone, but history has shown that man will not live in close contact with deadly beasts indefinitely, and the grief of so-called “rightists” rings hollow when it is claimed to be for someone that they never knew.

Personally, I don’t care much what ignorant people think, but often in the night I lie awake and wonder how many of the ivory tower dwellers would sacrifice their own life or their own child to the idol of the elephant, and I wonder what has become of Hope and Faith. I wonder if they live. I wonder if the elephants have come again to take their food. I wonder what will happen to Faith when the malnutrition that stalks them both weakens her mother to the point where she can no longer walk to the well by the little church at Chakupaleza. And I am haunted by a vision of Hope, kneeling in her doorway and sobbing as she bangs upon her only pan and prays to the white man’s God for someone to come and save them from the elephant.

Sporting Classics has compiled this remarkable anthology showcasing the best African adventures published in our award-winning magazine.

Ruark, Capstick, Roosevelt, Markham – the legends in outdoor literature are all here, sharing their stories of deadly encounters with dangerous game, of bizarre run-ins with witch doctors, gorillas and man-eaters, of safaris into the uncharted wilds of deepest Africa.

Illustrated by world-renowned artist Bob Kuhn, AFRICA features more than 400 pages of unforgettable stories by some of the finest professional hunters and writers of sporting adventure. Buy Now