He returned to find that someone had broken into his house . . . the only thing missing was the Parker.

Red Timmons disappeared while hunting chukar partridge on a cold day in January. According to Sheriff Charlotte Beingasser, he drowned in the Salmon River, a few miles from White Bird, Idaho. The local folks thought it strange. Chukar hunters have been known to fall from cliffs, accidentally shoot themselves or die from heart attacks. But no one had ever heard of a chukar hunter drowning, unless it involved a boat accident getting from one hunting spot to another. Red Timmons didn’t hunt chukars from a boat. He did it the old-fashioned way, climbing the high, brown hills.

Red Timmons disappeared while hunting chukar partridge on a cold day in January. According to Sheriff Charlotte Beingasser, he drowned in the Salmon River, a few miles from White Bird, Idaho. The local folks thought it strange. Chukar hunters have been known to fall from cliffs, accidentally shoot themselves or die from heart attacks. But no one had ever heard of a chukar hunter drowning, unless it involved a boat accident getting from one hunting spot to another. Red Timmons didn’t hunt chukars from a boat. He did it the old-fashioned way, climbing the high, brown hills.

Searchers found boot prints and dog tracks in the snow leading out onto a shelf of river ice. The tracks ended at the edge of the ice about 30 yards from shore where a few chukar feathers lay scattered in the snow. Propped against a tree along the riverbank they found a loaded Remington Wingmaster Model 870 shotgun, presumably belonging to the deceased.

The theory went as follows: Timmons, hunting above the river, winged a chukar that sailed downslope, landing on the ice shelf. His Brittany, Two Dot, followed the bird onto the ice and ended up in the river. Timmons, trying to save his dog, met the same fate.

It was a plausible theory because Timmons, despite his reputation for shady financial dealings, was known as the kind of man who would risk his life to save a dog. But the search and rescue workers didn’t find Red’s body, nor that of Two Dot.

“They’ll turn up downriver in the spring,” opined Sheriff Beingasser. But after a year there was still no sign of the bodies.

Timmons’ sometime hunting partner, Heath Vawter, remained skeptical, but kept his suspicions to himself. Vawter had hunted chukars with Timmons many times and had never known him to carry that Remington pump. A dedicated double gun man, Timmons favored a vintage 16-gauge L.C. Smith for everything but waterfowling. The Eagle-Grade “Elsie” ranked in his affections only behind Two Dot and his golden-haired wife, Maddie.

Maddie played the distraught widow convincingly enough. She kept her job at the local grocery and soldiered on bravely with day-to-day life. After a period of mourning, she dated the occasional cowboy or logger, but romance never blossomed. In time, Heath Vawter himself tried to console her. One night at the Silver Dollar Bar, after they’d gone a few rounds with Jose Cuervo, Heath laid his cards on the table. “Let’s move in together, Maddie,” he whispered in her ear.

“I can’t, Heath.”

“Why not?”

“I need more time,” she said, without elaborating.

A side from Maddie, Two Dot and the Elsie, Timmons had one other abiding passion, bordering on lust: A beautifully engraved Parker A-I Special 12-gauge shotgun made in 1908, now belonging to Heath Vawter. It was a case of unrequited love, because Heath had no intention of giving up the Parker.

“You fixing to sell that gun, Heath?” Red liked to ask, a smile lurking under his drooping red mustache.

“No, Red, I’m not fixing to sell it.”

Although the gun “belonged” to Heath, it had come into his possession under circumstances that some people might have found distasteful, or even illegal. Such people, Heath mused, are philistines who have no appreciation for handcrafted American double guns.

Although the gun “belonged” to Heath, it had come into his possession under circumstances that some people might have found distasteful, or even illegal. Such people, Heath mused, are philistines who have no appreciation for handcrafted American double guns.

Heath had befriended a local trapshooter named A.O. Plummer when he first moved to White Bird. Tall and ramrod straight, A.O. cut an imposing figure with his Open Road Stetson, high cheekbones, and piercing blue eyes. Despite his 72 years, A.O. could still run a score in the high 90s with his old Ithaca single barrel trap gun.

A youthful A.O., so the story went, had won enough money in big-time trap and live pigeon shoots in Europe to buy a modest ranch outside of Grangeville. Over the years, as his reflexes, nerves and luck began to wane, A.O.’s shooting fortunes reversed. As the local wags put it, A.O. eventually “shot the ranch out the end of his gun barrel.” Forced to sell everything but his house, he went to work for other, more prosperous landowners.

In the first autumn of their acquaintance, A.O. and Heath hunted the stubble fields above the Salmon River gorge for Hungarian partridge. When A.O.’s Gordon setter, Nellie, drew to a point, he routinely clipped two Huns from the covey with his Parker. At first Heath was lucky to bag a single bird from a covey rise, but he slowly got the knack. In time he acquired a gundog of his own, a female Brittany named Spoon, littermate to Red Timmons’ Two Dot.

That winter, afflicted with prostate cancer, A.O. suffered declining health. The following summer the two men talked about the dove opener in September.

“If I’m still kickin’,” said A.O. with a wry smile, “we’ll set up in the trees at the Bolstad place.”

When opening morning came, Heath helped a frail A.O. to a shady spot at the edge of a grainfield where doves had been using. Shortly after dawn A.O. plucked a high-flying bird from a group of three winging overhead, sat down in his folding chair and unloaded the Parker.

“That’s it,” he said. ‘When my time comes, and it ain’t far off, I want to remember how I made a good shot on my last high dove.”

“It may not be your last dove,” Heath said. “You may beat this thing yet.”

A.O. ignored him and continued. “I want you to have the Parker,” he said, patting the gun fondly. “My granddad special-ordered it in 1908. And I want you to promise you’ll take care of Nellie for me.”

“You have my word on that.”

Not long after his last dove hunt, A.O. moved to a nursing home in Grangeville, leaving Nellie in Heath’s care. Heath visited a couple of times a week through September and October, Nellie in tow, regaling him with tales of staunch points and covey rises.

“The wagon wheel covey at the Miller place has a dozen birds this year,” Heath would report, bringing a smile to the old man’s face.

On a rainy morning a few days after Thanksgiving, A.O. passed away. His wife had died years earlier and they’d had no children. That night, while Nellie and Spoon waited in the truck, Heath crawled through an unlocked window at A.O.’s house and liberated the Parker. A week later, having been notified by Sheriff Beingasser, a niece from Portland showed up with her tattooed boyfriend to claim A.O.’s few belongings.

“I believe he had some guns,” said the sheriff, who had retrieved A.O.’s house key from the nursing home. A.O. had not left a will. Because Heath had expressed to the sheriff his interest in making the niece an offer on the guns, he’d been invited along.

“As far as I know,” said Heath, “A.O. had an Ithaca trap gun and I believe an old Smith & Wesson .38 revolver. Those are the only guns I’m aware of. If you folks would like to sell them, I’d be happy to make you an offer.”

“As far as I know,” said Heath, “A.O. had an Ithaca trap gun and I believe an old Smith & Wesson .38 revolver. Those are the only guns I’m aware of. If you folks would like to sell them, I’d be happy to make you an offer.”

“We’ll be taking them back to Portland,” the boyfriend said curtly.

On a foggy morning in December, a month before Red Timmons vanished into the dark currents of the Salmon River, Spoon nearly met her maker. Hunting chukars above the Salmon River on White Bird Hill, Heath and Red caught a glimpse of Spoon on point near the edge of a fog-shrouded promontory. When the birds flushed wild, she charged after them and hurtled down a 20-foot cliff, landing in a heap in the rocks below.

Red was the first to reach the motionless dog. “She’s breathing,” called Red, “but it doesn’t look good.”

The two men took turns carrying Spoon off the mountain, a grueling slog that took the better part of an hour. They got Doc Larsen on the cell phone while racing to his veterinary clinic in Grangeville. Miraculously, Spoon had no broken bones, but an ultrasound showed internal injuries. With her ruptured spleen removed, Spoon slowly recovered.

Later that month Heath made a hip to Minnesota to spend Christmas with his ailing mother. He returned to find that someone had broken into his house in White Bird. The only thing missing was the Parker. He filed a theft report with Charlotte Beingasser, but doubted he’d ever see the gun again.

January brought the news of Red Timmons’ drowning. After the memorial service, life returned to normal in the sleepy town of White Bird. When more than a year had passed, Maddie Timmons received a $500,000 check from the life insurance company. She eventually moved away, back to her hometown of Spokane, some said. Down at the Silver Dollar, there was late-night talk about Red’s gambling debts. Not everyone believed he was dead.

Two years after Red’s disappearance, Heath Vawter, coming off a bout of walking pneumonia, decided the January sun and warmth of southern Arizona might do him good. He packed his clothing and hunting gear, whistled Spoon and Nellie into the truck, and headed south for a rental house in Tubac, south of Tucson.

Once settled in his new surroundings, Heath’s attention turned to the reclusive little bird known as the Mearns quail. His first outing on the Coronado National Forest found him driving upward through a forest of evergreen oaks and junipers to more than 5,000 feet. Turning off on a side road, he parked, uncrated the dogs and headed into the hills. Under the spreading branches of an oak tree, where grama grass and Texas bluestem formed a thick understory, Spoon stiffened on point and Nellie backed. When Heath scrambled up the slope and walked in front of the dogs, the covey flushed in a flurry of wings. He brought down a pretty polka-dotted male with the one shot he was able to get off. Later Nellie pointed a single, and he bagged a cinnamon-colored hen.

“A.O. would have enjoyed this, Nellie,” he said, patting the dog’s dark head when she delivered the bird. His next trip took him to Parker Canyon Lake in the Huachuca Mountains east of Nogales, a few miles north of the Mexican border. When he pulled into the Forest Service campground, with its old cement picnic tables, he noticed several trailers belonging to hunters. One of them, a canvas pop-up camper, had a Brittany tied in front. Next to the dog, an attractive woman with long blond hair sat in a camp chair reading a book. The dog had an orange spot over each eye, and the woman bore a striking resemblance to Maddie Timmons.

When Heath strolled over and stopped in front of her, the color drained from her face.

“Hi Maddie.”

The Brittany whined and strained at his rope.

“Two Dot, how are you?” asked Vawter, kneeling to scratch the dog behind his ears. “I’ve missed you.”

Maddie Sighed. “How’d you find us?”

“I remember Red talking about this campground. He said he spent some good times here as a kid, hunting quail with his dad and uncle.”

“You gonna drop a dime?” asked Maddie, her voice scarcely above a whisper.

“Damn right I am. Red hurt a lot of people back in White Bird. Just one question: How’d he pull it off? Disappearing without a trace, I mean?”

Maddie closed her book and laid it on the ground.

“I floated down the river in a raft right at dark and picked him up at the edge of the ice. No one saw us. We had a truck parked a mile downriver. We bought it off a farmer in Montana . . . cash deal, no title transfer, no paperwork. Red had enough cans of gas stashed in the back of the truck to get well south of Idaho without stopping. After that, he wore a disguise and paid for everything in cash. Slept in the truck. No credit cards, no paper trail. We planned it down to the last detail.”

“I floated down the river in a raft right at dark and picked him up at the edge of the ice. No one saw us. We had a truck parked a mile downriver. We bought it off a farmer in Montana . . . cash deal, no title transfer, no paperwork. Red had enough cans of gas stashed in the back of the truck to get well south of Idaho without stopping. After that, he wore a disguise and paid for everything in cash. Slept in the truck. No credit cards, no paper trail. We planned it down to the last detail.”

“Where’d he hide out all that time? I’m sure the insurance company did some investigating.”

“Mexico. Red grew up down here, and he knows how to cross the border without being seen. After we collected the insurance money and the heat was off, he just walked back across and met me here , at this campground. We have a little place in Rio Rico now and new identities. But we spend a month or so every winter hunting quail out of this campground. Just our luck to be he re when you rolled in.”

“Is that where he is now? Out hunting?”

“No, he’s been out all day with some boys from Nevada, looking for an English pointer that turned up missing yesterday. You know Red when it comes to dogs.”

An image suddenly flashed through Heath’s mind, an image he’d tried to forget. It was a vision of a sweating, exhausted Red Timmons, struggling to carry Spoon’s limp body down the treacherous slopes of White Bird Hill.

“Yeah, I know Red when it comes to dogs … and shotguns. Okay, Maddie, here’s the deal. Tell him if the Parker doesn’t show up at my house in Tubac in two weeks, I’ll have Charlotte Beingasser on speed dial. If I get the gun back, my lips are sealed.”

He scribbled his address on a scrap of paper and handed it to her. Then he gave her a long, loving look.

“You know, Maddie, I’m doing this for you.”

“No, Heath , you’re doing it for the shotgun. But that’s okay.”

A week later a UPS truck showed up at Heath ‘s house in Tubac with an oblong box. “You’ll need to sign,” said the driver.

When Heath ‘s trembling hands tore open the box, he found A.O. ‘s Parker inside. He couldn’t help but smile when he read this note taped to the barrels: “And they say there’s no honor among thieves.”

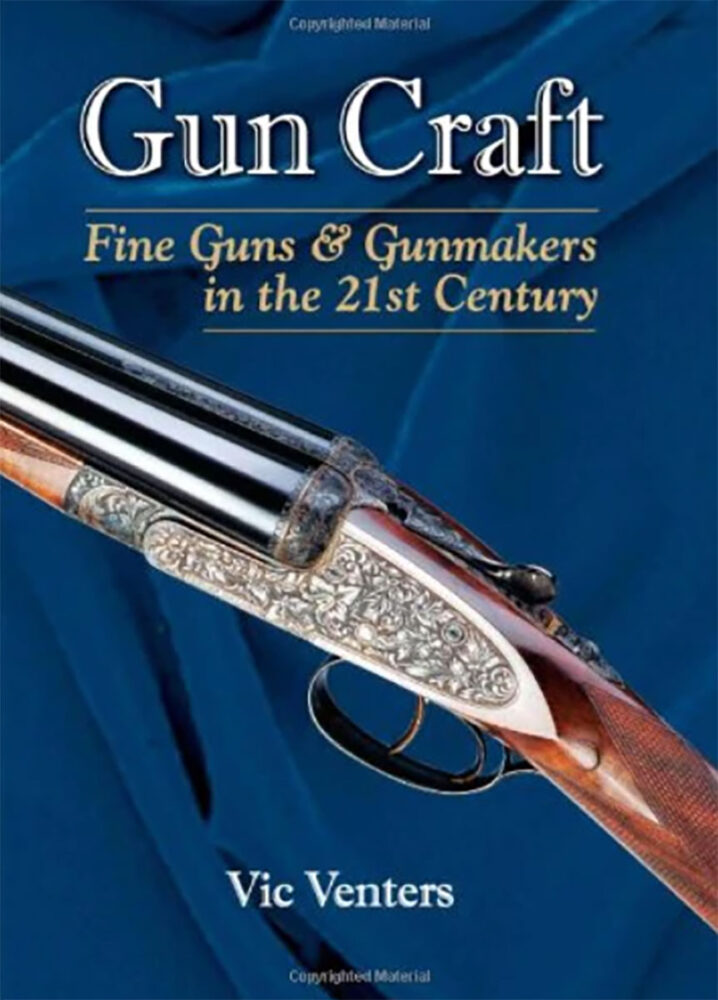

Gun Craft examines today’s artisanally made guns, as well as the craftsmen who make them. In it, the author takes the reader into the workshops and factories of the world’s best gunmakers, making their sometimes-arcane craft skills accessible and relevant to anyone who shoots, owns or collects fine guns. Each chapter explores a separate topic; each has been chosen, however, to provide readers with a unified insight into the complicated task of making hand-made guns in both Europe and the United States. Buy Now

Gun Craft examines today’s artisanally made guns, as well as the craftsmen who make them. In it, the author takes the reader into the workshops and factories of the world’s best gunmakers, making their sometimes-arcane craft skills accessible and relevant to anyone who shoots, owns or collects fine guns. Each chapter explores a separate topic; each has been chosen, however, to provide readers with a unified insight into the complicated task of making hand-made guns in both Europe and the United States. Buy Now