The President of the Old Duck Hunters’ Association, Inc., softly closed his back door and came down the steps in the near dark to stow a last armload of gear into the car. A match flared as he relit the battered brier, and from the top of a telephone pole came the triumphant morning music of a robin.

“Listen!” the old man whispered.

He got in the seat beside me, closed the car door without slamming it, cranked down a window and cocked an ear. By the very faint outdoors light and some light from the instrument board I watched Mister President. His eyes crinkled at the corners as the lone robin sang of mysterious and wonderful things in which he would take part on this, the first day of May.

The President whispered: “That guy is the first one up every morning. He gets the tallest pole. Likes to hear himself sing – like a man in a bathtub.”

The soloist on the pole was making music from a full heart and a full stomach Obviously he sang of a fine world for living in, with acres of lawns and plenty of worms. He seemed carried into ecstasy with the wonder of it all, for at times there was too much music in him to come out of one robin throat. Then he sounded like two robins. This made the Old Man grin all the more.

The singer on the pole still had the stage to himself when I backed the car down the driveway and headed east. Other autos were on the go, all rolling east from the head to Lake Superior to scores of trout streams that emerge in the north Wisconsin highland and run down to the greatest of freshwater lakes.

Mister President pulled his old brown mackinaw about him and tended the battered brier.

“That robin on the pole,” he mused. “The beggar can sing, but he won’t work. You think helped me dig worms last night? No sir! He came around after I finished and gobbled up the little ones I left. Ah, dear. When a man’s in love he’ll stop at nothing.”

Daylight built up slowly. There were scores of cars on the road, all of them with trout fishermen, many of them driving a little madly as is the way on opening day. We were in no hurry. Johnny Degerman has reserved our canoe. We passed through sleeping hamlets where windows were lit – more fishermen gulping breakfast.

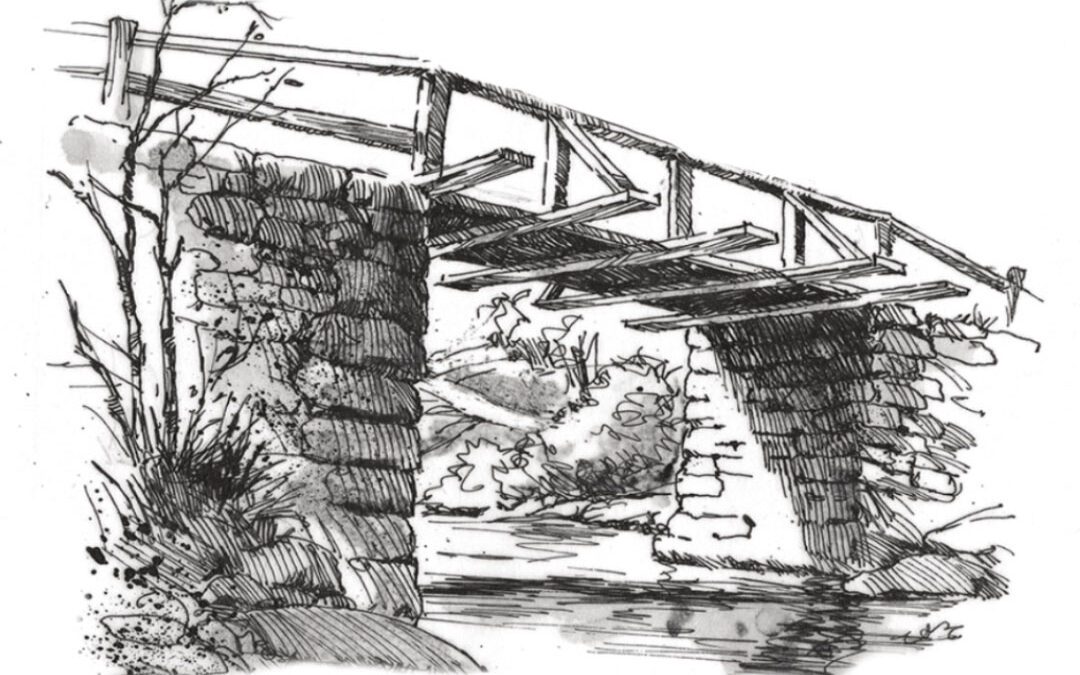

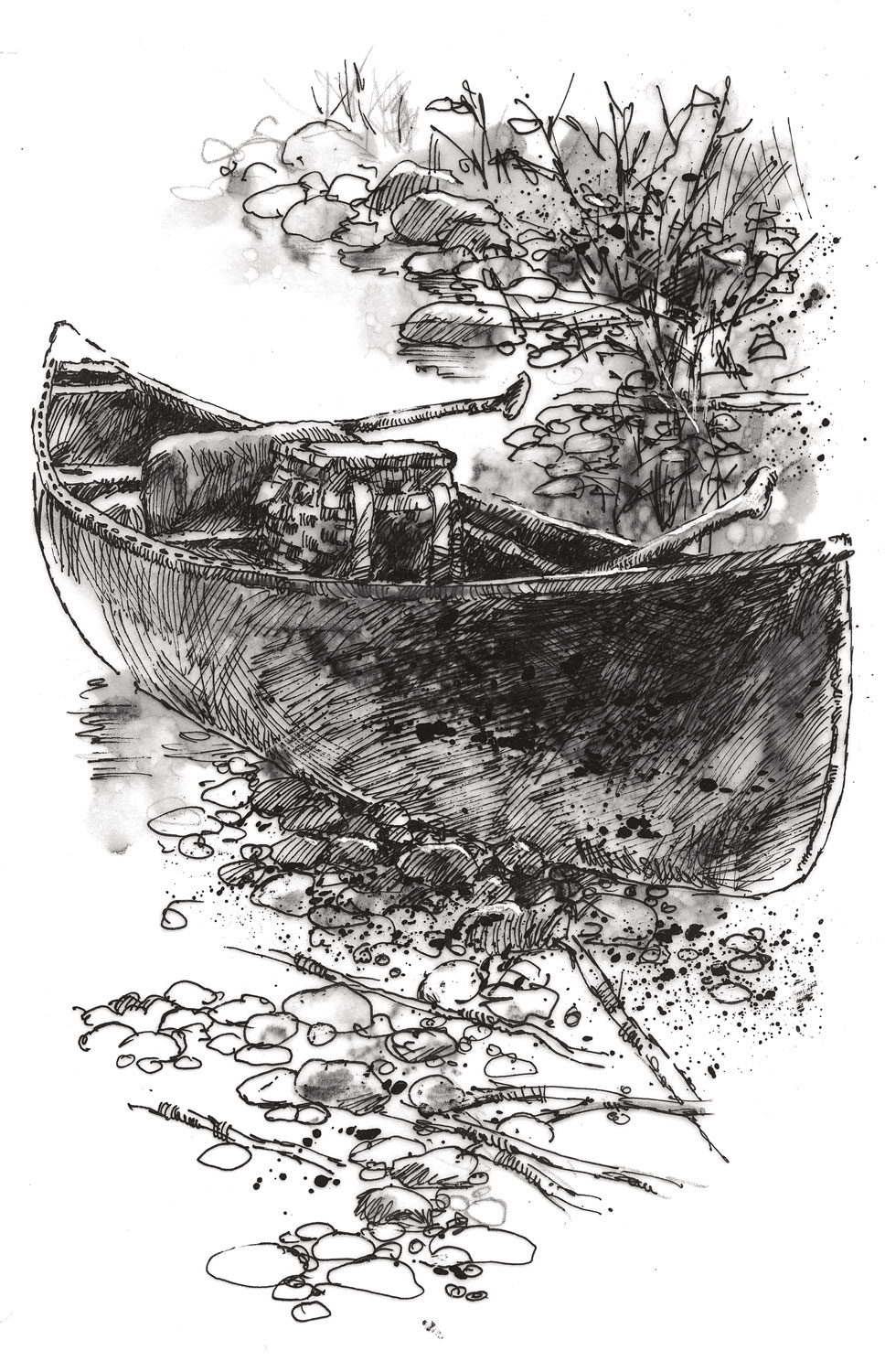

Beyond the village of Lake Nebagamon we went straight south over a crooked graved road to Stone’s Bridge on the upper Brule River. We were the first at the dock, as Johnny had guessed we would be. He had left a scribbled note on the bow chair of the canoe riding at the downstream end of a flotilla of twenty: “Mac, take this one.”

Mister President rigged his rod with the long grip while I loaded the canoe. It was fairly light as we shoved off, but there was no sign of the sun yet. The Brule took charge of the canoe, and we were off, the Old Man’s snaky brown line swishing over my head like the call of distant whippoorwills. The Old Duck Hunters’ Association fishes this river by ritual: the Old Man in the bow chair an hour, I in the stern with pole and paddle; then switch over for the next hour.

There is big magic in this lovely river, and never more than just before sunup of opening day. The brethren who have learned to love this stream will know how it can be.

Winter done. Waxwings murmuring in the cedars. The Brule sucking around the rocks. Dabs of fog rising here and there. A woodpecker hammering a rampike. The Bois Brule winding at the bottom of its deep valley, saying, “I’ve got ’em if you’re man enough to take ’em from me.”

We were not out of sight of Stone’s Bridge when the Old Man’s single wet coachman had found a good native brook about a foot long. It tore out from beneath brush and logs. I netted it and dropped it through the slot in the door of the live-well.

As is often the case on this river, Mister President was plagued with small rainbows. They are pugnacious, undersize busters willing to have a got at almost anything offered. These ridiculous midgets, thick in the belly, averaging five to six inches long, grab flies as large as No. 8s, then fling themselves hither and yon, as though they lick the world and everything in it.

We put the bridge behind us around the first bend and went on down between alders. The stream narrows here to about 20 feet in width, with deep water at the left bank where the alder tips trail Mister President nailed another native – a typical dark-bodied, red-bellied Brule ”speed” not smart like a brown, but bursting with vitality.

A half-mile from the bridge we knew the sun was up but that it would be awhile yet before it crept over the Norways on the high hills to flood the river. Mister President broached an idea: “Let’s shove on down fast for two good miles, just in case somebody from the bridge has the same idea.”

For half an hour we poled together, putting distance behind and passing up beautiful stretches of fly water. Never mind, there will be plenty of such good water down below. Yet it’s not an easy thing to pole when trout are dimpling. Then the hand itches for the feel of cork.

Below the Buckhorn, a luncheon ground marked by antlers nailed to a tree, Mister President went at it again. He feature that no lunker rainbows would be so far upstream. The spawning run had been early. So he retained his light leader.

To be sure, it happened; it always does. In a place where the Brule spreads out over washed gravel, a rainbow of about four pounds offered battle. It was all over in something like six seconds. The fish shot off the shoal to deep water, plunged downstream in the main current – and that’s all there was to it.

“Somebody in this organization,” Mister President wailed, “had ought to fine me about $10,000.”

“Put on a leader. There are a few big ones here anyway. I know a place.”

He re-rigged while I poled to the next likely spot for a big one Brule rainbows are great ones for lying over gravel beds in pretty swift current. I have seen scores of them lying so, up to ten pounds and better, in areas so restricted that they scrap among themselves for elbowroom.

The Old Man dug up a bass leader and with a dark, bass-sized bucktail, good Brule medicine on big fish, flailed the water. He failed to get a roll and his hour was up, so we exchanged places. I was using Mr. President’s outfit. He let the canoe work down to the end of this gravel bed.

Wham! What a fine word, that for rainbows. This fellow did as all smart rainbows do – work into the current, lie in it crosswise, then jerk, jerk, jerk! They have plenty of power and they know how to let the current add to it. I pinned my hopes on that bass leader. When the fish broke, he looked pretty good, deep in the middle. As soon as Mister President saw him, he ordered: “Hit the drink!”

Overboard the water was cold as sin. The Old Man knew what he was doing when he shouted that advice. He knew that a wading fisherman had more maneuverability than one in the most skillfully handled boat. The rainbow took me downstream about 50 yards. Once off the gravel bed there were holes to contend with, some of them right against the bank. Sometimes I got through them only by hanging to cedar boughs. Mister President followed in the canoe.

The rainbow gave me hell in more ways than one. Not the least of it was the cold of the river. The fish just decided: “If you’re going to fight me, you do it on my home grounds.”

When the jerking had subsided, I heard a splashing behind me. It was the Old Man in there with me, belly-deep. No waders. He was busy unwinding the white cotton mesh of a four-foot net as he waded below me and below the sulking fish. He did not miss on the first pass. Slabsides went to his destiny in the long white meshes.

The two of us got ashore and made a fire. We had to open the live-well cover to put the big rainbow inside. He was too much fish to go through the slot. We stripped before the fire and dried out. The sun had finally found the bottom of the valley. It felt mighty good. We boiled coffee and fried the two brookies.

If you ever get to fish the Brule, bring along a little bacon, some fresh homemade bread and a chunk of butter. And a frying pan.

It came Mister President’s turn to regain the bow chair. The sun was high and the day warm. He returned to a light leader and small wet flies. Under such conditions he swears by such flies as Cowdungs, Hare’s Ears and Brown Hackles.

He picked up some small native and a few flyweight rainbows, and so did I when it came my turn to ride the prow chair. These went into the livewell where Slabsides announced his living presence every whipstitch by banging his prison wall with a broad tail. It’s good to hear them thump like that.

After the noon hour Mister President announced, “We’ll go ashore here.”

The Old Duck Hunters always go ashore at this place, which is May’s Rips, six miles downstream from the put-in bridge. It’s a place where the Brule is beginning to feel its oats and starting to make some downhill jumps on its way to Gitche Gumee.

“I can eat ’em twice a day, and then some,” said Mister President, busy with the skillet.

We dried our clothes some more. We spread a couple of blankets on a cedar knoll and lazily watched other canoes, with other fishermen, come down the waters which we had explored first in the season. We listed to the croaks of wheeling ravens and the talk of the river elbowing down through May’s Rips, and also we listened to the dear music of the white-throated sparrow, which sounds so sad and makes trout fishermen so happy.

We dozed. Mister President was snoring when I awoke. He aroused slowly.

“Dammit!” he said. “I got a crick in my left shoulder. Dunno as I’ll be much good poling back upstream.”

There was evidence that the three hours of repose had stiffened his shoulder. It seemed the ground damp had come right up through the blanket.

“But my right shoulder’s all right,” he observed.

“You can swing a fly rod?”

“It’ll hurt, but I can do it.”

I took over the poling and he seized the bamboo scepter and moved in to the throne in the bow. Now it was upstream fishing with floating flies. The time of day was excellent for such business. It had been warm enough to produce a sustained hatch of gray-blue fliers, lots of them. A brown bivisible, size 12, did the trick. A good number of pan-warmers joined Slabsides in the live-well.

“But there ain’t much to show the neighbors except that rainbow,” Mister President pointed out.

In one still, deep pool the Old Man bit through the gut, stuck the floater in his hat-band and dunked with worms shamelessly and successfully for brown which would not surface. He took three. One, he insisted, would “go pound and a half on our butcher’s scale.”

Upper Brule browns in those deep holes are challengers. There are plenty of them, all very sharp-witted, or cautious, which amounts to the same thing for a fish. Given a dark, warm, windy day over these holes, a man has a fair chance to show them who’s boss. On most any other kind of day they just lie there and snicker at you.

The shadows of the cedars on the river stretched out. Clouds riding a southwest wind formed blackly. Nighthawks swooped. It would rain before we made Stone’s Bridge. Mister President put on his mackinaw and kept fishing. The rain stabbed violently at the Brule.

In ten minutes it was over and the nighthawks were diving once more. The sun came out strong. A porky swam the stream, floating high. The rain made everything smell good. Mister President loosened the button on his mackinaw and shook off the raindrops. He said, “My left shoulder is pretty creaky.”

I poled on upstream and he dozed in the sun. From my place in the stern I could see more of the gray of his hair as his head fell forward. Slab sides thumped in the live-well.

My hand itched for cork, as fish were rising. But it would not be the right thing to wake up the Old Man. The Old Duck Hunters’ junior membership opposes such nonsense.

There is a place about a mile and a half below Stone’s Bridge where the Brule twists and narrows among rocks and captured logs and brush. It was here where the itching rod hand became too much to ignore. I crawled forward and got the rod, crawled back to the stern and worked paddle and rod together, which takes some doing, unless you are of a piece with some Brule guides, which I am not.

A good fish was feeding boldly on the left bank, right under the brush. I managed to keep the canoe in position long enough to lay a fly in the right spot above him. It floated down. He just walked over and sucked it in. I dropped the paddle and let the canoe do what it would.

That brown was not more than a two-pounder. But he put a set in the rod on his first dash. It is not easy to handle a canoe and a brown at once in quick current. Luck and good tackle held him. He went under the canoe and then downstream while the canoe yawed in the current.

“Hit the drink!” It was the Old Man, suddenly awake, yellowing good advice again. In I went. The water seemed just as cold. And downstream went Mister Brown to a snaggy hole below a small rapids.

This time the President of the Old Duck Hunters’ Association did not join me. He did the entire job of coaching from the bow-chair throne. Sometimes he cussed a little, as when I let the fish get in under the bank. He hung on to cedar branches to keep the canoe from drifting down on top of the battle. Then he flung the net to me, and I grabbed its floating wood handle as it went by.

So eventually I came dripping back into the canoe with a nice fish and a badly set tip joint on a grand old trout rod. Mister President had the cover of the live-well wide open for me. He looked in on the welter of trout there. Then he took out his “gold watch and chain” and noted the time. He said we could just make it back to Stone’s Bridge before dark if he poled – in the stern.

Unloading at the bridge, I asked him, “How come you could pole up a mile and a half of current with that sore shoulders?”

“Sore shoulder? Oh, that. Funny the way them aches and pains come and go.”

Editor’s Note: “Hit the Drink” is reprinted courtesy of Willow Creek Press; www.willowcreekpress.com.