Standing before an audience seated around him in an open field was a stout middle-aged man wearing a shooting vest and a white flat cap emblazoned with a big red “W.” In his left hand he held a Winchester Model 63 autoloader .22 rifle and in his right hand, a small wooden block. He jabbered to the audience non-stop as he tossed wood blocks into the air and split them with practiced ease.

Next, he tossed marbles into the air and casually smashed every one while telling the audience “They are not hard to hit folks, just easy to miss.” Finally, a metal washer about the size of a quarter was thrown high into the air and at the sound of the rimfire rifle, it fell to the ground, apparently untouched. “He missed!” someone in the audience said. The shooter explained that he must have shot right through the hole in the washer.

The audience laughed at the absurdity of being able to actually shoot through the hole of a washer in mid air. Just to prove his point, he put a stamp over the hole and threw it up once again. At the next shot, the washer again fell, apparently untouched by the bullet. He then asked an audience member to retrieve the washer and hold it up so everyone could clearly see the .22 cal. bullet hole through the stamp! The audience erupted into applause. He then hurled four more washers into the air and proceeded to shoot the edge of each washer to make it jump left, right, up or spin in the air. He would later tell a reporter that “It’s the toughest stunt I do. The reason that one’s so hard is that I have to hit the washers on the side to guide them. It’s not hard to hit a coin in the middle, but it’s hard to hit a washer on the side.”

That shooter was none other than Herb Parsons, arguably America’s most skillful exhibition shooter and aptly named the “Wizard of Winchester.”

Exhibition shooting was a quintessentially American form of entertainment. During its heyday, which spanned from roughly the late 1870s to the mid 1900s, keen-eyed shooters could be found demonstrating their prowess with pistols, rifles and shotguns at state and county fairs, gun clubs, vaudeville theaters, circuses, rodeos and venues such as the Wild West Show. In their day, these shooters were admired for their skill much like professional athletes are today, and every farm boy with a .22 wanted to duplicate their shots.

Notable among these sharpshooters were William Frank “Doc” Carver and John “Doc” Holiday. Both dentists who gave up the drill in favor of exhibition shooting. In the late 1800s we also had Captain A.H. Bogardus. He started out as an Illinois market hunter and performed in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. However, he is perhaps best known for inventing a trap used to launch glass balls, the forerunner to our modern clay pigeon trap.

Also coming to fame at this time was a petite market gunner from Ohio. Phoebe Ann Mosley, better known as “Little Sure Shot” or Annie Oakley, was discovered in Cincinnati by Frank Butler, another exhibition shooter of the day. They eventually married and toured together for many years. Another notable husband and wife team were Adolph “Ad” and Elizabeth “Plinky” Topperwein. Ad was an exhibition shooter for Winchester beginning in 1901 and eventually passed the torch to Herb Parsons.

Other, more recent, shooters who come to mind are Bob Mundon, Tom Knapp (CZ-USA, Benelli, Federal), Ed McGivern (Smith & Wesson), Billy Hill (Remington) and another husband and wife team, Ernie and Dot Lind, who shot for Winchester-Western.

Herb Parsons was born to a hunting family on a farm in west Tennessee on May 5, 1908. From an early age, he was smitten with shooting and hunting and shot his first game bird, a quail, on the wing with a single-shot .22 rifle when he was only seven years old. He practiced shooting continuously throughout his childhood and saved every penny he could to purchase ammunition.

It wasn’t long before his reputation for being a crack shot spread. Two notable events occurred in his early years that led him to become an exhibition shooter. While still a freshman in high school, Parsons had the opportunity to witness the great Winchester Exhibition shooter, Ad Topperwein. It was at that point he decided that exhibition shooting was what he wanted to do for a living. Secondly, Parsons had the chance to hunt with a district salesman from Winchester-Western. That individual recognized Parsons’ special talent and helped him land a job with the company.

In 1929 at the age of 20, Parsons began his career with Winchester as a regional salesman covering the entire state of Mississippi. He soon realized that he could boost local sales by demonstrating his shooting skills with Winchester ammunition and firearms. His break into formal exhibition shooting came in the early 1930s, when Topperwein began looking for a successor due to his failing eyesight. Initially, Parsons shadowed Topperwein and his wife to learn the finer points of exhibition shooting before working on his own. Both men were adamant about never using trickery or rigged shots in their performances. What you saw was the product of pure skill, lots of practice and a mountain of ammunition.

Parsons’ remarkable marksmanship, smooth delivery and loquaciousness made him a natural showman and his efforts definitely increased firearm and ammunition sales wherever he went. His association with Winchester lasted for more than three decades and was unabated except during the war years when he became a gunnery instructor for the U.S. Army Air Corps. Parsons taught fighter pilots how to lead aerial targets while on the skeet field. He also instructed infantry soldiers how to properly squeeze a rifle’s trigger and how to control an automatic weapon. He also traveled to U.S. military bases around the country, performing for the troops and improving morale wherever he went.

Whether it was pulverizing oranges with a centerfire rifle, scrambling eggs he tossed from between his legs, making coleslaw from heads of cabbage, exploding watermelons stuffed with dynamite or powdering seven hand-thrown clays with a Model 12 pump shotgun, he always kept his audience entranced. The genial Parsons kept up a constant rapid fire gabble with his audience, mixing humor and homespun wisdom on sportsmanship and firearm safety with his shooting prowess.

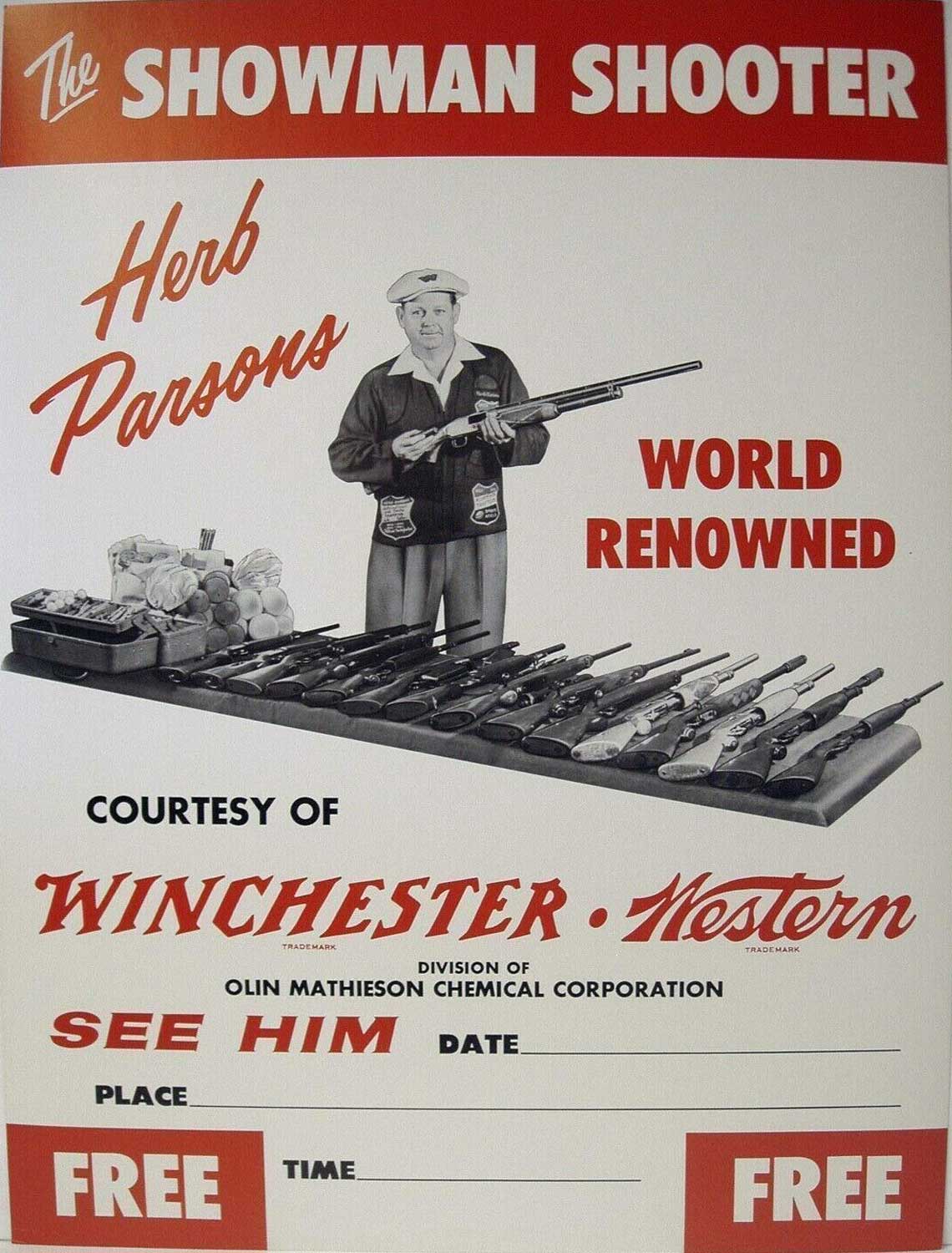

During an hour-long routine, he would fire 700 to 800 rounds of ammunition from more than a dozen different rifles and shotguns. He might run two shows in a day, often hundreds of miles apart, as well as conducting promotional visits to radio stations and television studios. For pure showmanship, skill and sheer spectacle, Herb Parsons was arguably the greatest exhibition shooter of his time.

Amid all that fancy shooting, it’s easy to forget that Parsons’ true job was to boost firearm and ammunition sales for Winchester. He was first and foremost a salesman for the company and was held to an ambitious sales quota for the local stores in the area and an even tighter travel allowance. He was on the road for weeks at a time, living in hotel rooms while he crisscrossed the country in a Winchester Red Pontiac station wagon. That car was literally stuffed with all of his firearms, ammunition, props and often a case of dynamite! Mounted to the top of the car were two large Winchester Shotgun Shells that cleverly held a pair of loudspeakers for his PA system. Imagine seeing something like that cruising down the expressway today! Throughout the 1950s, Parsons performed more than 130 shows a year and, at his peak, was booked three years in advance.

In addition to his exhibition shooting, Parsons also enjoyed competitive trap shooting and won the 1954 Grand National Trap Shoot and was a member of the All-American trapshooting team. He was posthumously inducted into the American Trapshooting Hall of Fame in Vandalia, Ohio. He was also a champion duck caller—twice winning the National Duck Calling Contest at Stuttgart, Arkansas, as well as the International Duck Calling Contest at Crowley, Louisiana.

He also had popular records on how to call ducks and crows, which are collectors’ items today. Parsons even dabbled in the movie industry during his career. He starred in a short film called “Showman Shooter” that highlighted his shooting feats. In 1950, he served as the technical consultant for the iconic Western film “Winchester 73” starring Jimmy Stewart and Shelly Winters. During the shooting contest scene, it was Parsons who stood off camera and, using his own Model 71 lever-action rifle, shot the metal disks as they were thrown into the air while Jimmy Stewart fired blanks. Parsons was also friends with a number of stars from that era and shot trap with both Clark Gable and Roy Rogers.

It should be mentioned here that Parsons sometimes had his sons accompany him on these trips. He was immensely proud of his boys and, although they were young and the shotguns they used were nearly as long as they were, both boys became very keen shots and were a valued part of the show. Beginning when they were only eight or nine years old, the boys could shoot four clays thrown into the air by their dad using a pump shotgun.

The audience loved the boy’s shooting performance and after the applause died down, Parsons would often exclaim in mock annoyance “Hey, who’s show is this anyway?”

Unfortunately, Parsons’ life was cut short at the age of 51 when on July 19, 1959 he suffered a fatal heart attack following a surgery to repair a hiatal hernia. Parsons was a close friend of John Olin, (his boss and vice-president of Winchester-Western at the time). A little known fact is that after Parsons died, Mr. Olin set up an anonymous educational trust for the two boys. Both Herbert Jr. and Lynn made good use of that trust. Herbert Jr. received his M.D. degree and became a well-respected general surgeon in Ohio until his passing in 2012 and Lynne received his Ph.D. degree in horticulture and was a professor at Texas A&M for many years. The book Showman Shooter, which was compiled by the boys, is dedicated to Mr. Olin for his friendship and generosity.

The era of the great exhibition shooters has now passed into the annals of history and we will likely never see anything like it again. This is not to imply that exhibition shooters no longer exist, but both their numbers and notoriety they enjoy in mainstream culture pale in comparison to those early shooters during what was unquestionably the golden era of exhibition shooting. Instead, many firearms and ammunition companies such as Smith & Wesson, Colt, Eley, Benelli, Federal, Beretta and Lapua, now sponsor competitive shooting teams to promote their products. Among such notables as the Topperweins, Bogardus, Oakley, Carver and Holiday, Herb Parsons stands out as perhaps the greatest of them all for his skill, speed, delivery and showmanship. He left a legacy that is still with us today, more than 60 years after his passing.

For those interested in learning more about the life and career of Herb Parsons, a book compiled by his sons entitled Showman Shooter, The Life and Times of Herb Parsons, is still available, as are copies of his movie “Showman Shooter.” A display of his firearms can be found in the Cody Firearms Museum of the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody, Wyoming, and a collection of his duck calling championship trophies can be found at the Ducks Unlimited headquarters in Memphis, Tennessee. ν