Hal, a Dacotah was no ordinary Dakota. A frontiersman, politician and fur trader—Hal was a white man who, in 1839, would find himself on an adventure of a lifetime along the half-frozen Cedar River of Iowa.

It was late November, and it was cold. A sub-zero cold front had pushed its way into the north country, casting single digit temperatures that brought an abrupt end to a pleasant autumn. Almost overnight, hibernating animals fled to their dens, wetlands iced over and migrating birds picked up and headed southward. Winter was fast approaching, and for the Dakota/Sioux, it was the time to hunt, the time to head into the woods and river bottoms in search of game that could sustain them through the long winter ahead.

The Mdewakanton Dakota band of Wasuwicaztaxni, or “Bad Hail,” were heading south for an annual hunt. From their village in Minnesota, they struck their lodges and traveled south to the Cedar River. There, they would pursue the whitetail deer that were in the midst of their breeding season. Tagging along for the hunt was Hal, a white man and well-known frontiersman from Ft. Snelling.

Indians in the Snow (circa 1880) by William Hahn.

Hal was no stranger to the north country—he was a veteran fur trader and adept to life on the frontier. His real name was Henry Hastings Sibley—a name that earned respect from both whites and Indians alike—Hal was the pseudonym Sibley used to pen his adventures for readers of The Spirit of the Times, a publication back in New York.

Sibley was born in 1811 at Detroit, Michigan. His father, Judge Solomon Sibley, was embroiled in the region’s politics, and when war broke out in 1812, commanded a force of militia that was defending Ft. Detroit. At the age of 18 months, Sibley would be one of many civilians huddled in the fort’s confines as it was attacked by British General Isaac Brock and the famed Shawnee war chief, Tecumseh. His mother would later remark that she held little Henry in one hand while making cartridges in the other. The battle was lost, and the Sibley family were turned into refugees. They would return to the fort one year later, however, as it was retaken by U.S. forces under the command of William Henry Harrison.

Sibley spent his formative years in Michigan, and at the request of his father, studied law at the Academy of Detroit. By the age of 17, however, Sibley could study no more. He found the pursuit of law to be “irksome” and yearned for a life in the wilderness. In 1828 he traveled to St. Marie, a fur trading center that catered to both the United States and Canada. There, he found work as a clerk, but slowly began to rise through the ranks and in 1834, moved to Mendota where he became head of the American Fur Company—Sioux Outfit.

In his later years, Sibley would enter the political ring and even rise to the rank of Governor of Minnesota, yet it was his time spent in the fur trade that solidified his status as a frontiersman and solidified his relationship with the Dakota when he married a young Mdewakanton woman named Tahshinaohindoway, or Red Blanket Woman.

The union was made in the hunting camp along the Cedar River and was done in a la facon du pays fashion—a practice of common law marriage that was typical between white fur traders and Native Americans. It was arranged by Bad Hail, who happened to be Red Blanket Woman’s father. In his eyes the marriage would create an unbreakable kinship tie between he and the powerful Henry Sibley.

In 1839, the north country was a mecca of wildlife—deer, black bear, wolves, prairie chickens and bison were all common on the frontier. Hal was, of course, just as familiar with the land and the animals that walked upon it as the Dakota hunting party he was a part of. Together, they made camp along the river, and in an effort not to overhunt the area, created a stringent set of rules that all the hunters were obliged to follow. The rules included a limit to which could be hunted as well as a boundary that could not be crossed. Those who broke the rules were punished, the most severe form of which included having the offender’s coat ripped from their body and destroyed.

With rules set, the hunters woke the first morning at dawn and ventured into the countryside in search of game. Hal set out on horseback. Alongside him was his old friend and faithful companion Lion, Hal’s wolfdog. Deer seemed scarce that morning and Hal was finding little success. As he rode along the river, he spied a small group of a dozen mallards resting on the frosty bank. The river was one of the boundaries set out in the rules, yet Hal supposed that since he would not have to cross the river for the kill, the birds were fair game, and he and his new wife would be treated to some fat ducks for supper.

Hal leisurely extracted the lead balls from his double barrel and then loaded it with No. 2 bird shot. He hitched his horse some distance away from the river and motioned for Lion to stay there. With the icy wind at his favor, Hal snuck along the riverbank to a large willow tree from which he could take a clean shot.

The ducks were nearly motionless and totally unaware of the hunter who crouched in the willows. Nine had their bills nestled beneath their wings, asleep, and the other three were busy nipping through their puffed-out feathers. Hal shouldered the gun and slowly pulled the hammers back with a mechanical sounding “click.” He took a deep breath, exhaled slowly, and braced himself for the charge that was about to exit the weapon.

All did not go as planned.

Suddenly, and seemingly out of nowhere, a heavy hand fell upon Hal’s shoulder, and he was spun around to face a large Dakota man, a fellow hunter from the party named Wacootah. The hunter scolded Hal for hunting over the border. He grabbed the gun out of Hal’s hands and raised it in the air as if to break the weapon. Hal intercepted the gun as Wacootah brought it down, “If you break my gun,” he said, “I will surely break your head.” As per the rules, a weapon could not be rendered unserviceable as punishment, so Wacootah handed it back and instead snatched Hal’s fur hat off his head and stowed it under his belt. Hal tried to protest, wished to argue that he was not crossing the border, yet was not given the chance and was ordered back to the camp.

He dared not disobey. Hal was a guest, but more importantly, the temperature was near zero and he was now bareheaded. He prayed that his coat would not be destroyed as it was the finest in camp and the only one he possessed. To clear his name, Hal ordered a massive feast to be made and invited the other hunters into his lodge to feast. He apologized, explained that he did not know he was breaking the rules, then offered the food. They ate, they smoked and they left. No further punishment was made, yet the hat was not returned.

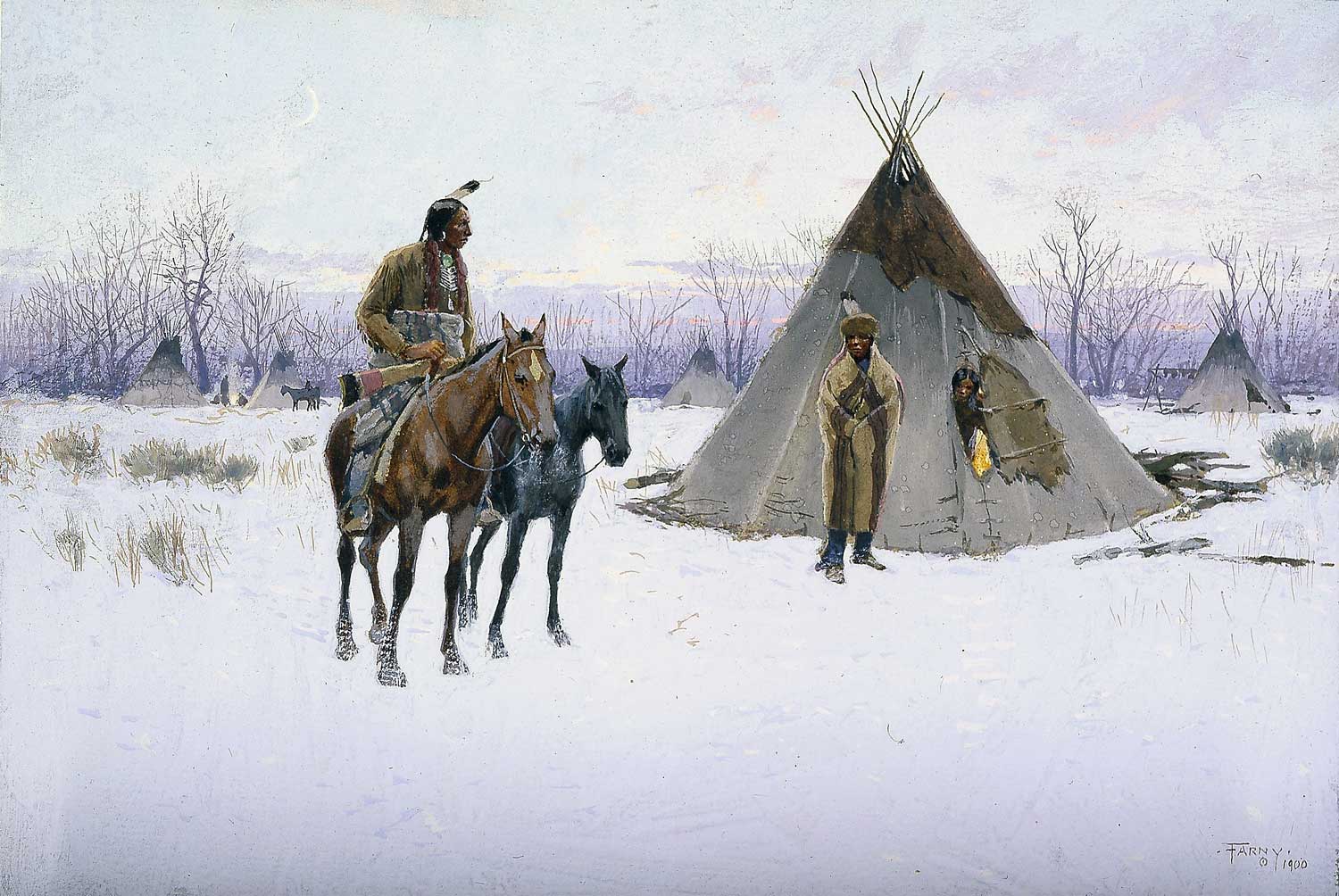

Early Start (1900) by Henry F. Farny.

The Noble Lion

The following morning found Hal paired with Wacootah and another younger hunter he did not know. The three set out on horseback in hopes that some deer could be acquired on this second day of the hunt. Just as the morning prior, Lion trotted happily alongside his owner as the small group set out from camp.

No more than a mile from camp, a deer sprang from the willow thicket ahead of the group. It was a large buck and had a heavy, gray coat to accent thick, polished antlers. The deer exploded from the brush and sprinted toward the woodline. Hal shouldered his gun and sent a carefully aimed ball soaring through the air. The distance proved to be too far, however, and the ball missed the deer as it sprinted away unharmed. The deer and the gunshot roused the dog, however, and Lion raced excitedly toward where the buck jumped into the woods. Hal yelled for his return, fearing the dog would be gored or worse, yet Lion had no intention of stopping.

The chase was on. Lion’s ears lay flat and stretched backward as he sprinted headlong toward the deer. The dog was fast, and in mere minutes was on the deer’s haunches and ready to pounce. The buck, while trying to avoid tangling his antlers in the brush, was forced to slow just long enough to allow Lion to spring an attack and sink his muzzle into the buck’s neck like a wild timber wolf. With a thunderous crash, the buck fell to the ground. It thrashed, kicked its hind legs and shook its head in an attempt to throw the dog from its back.

Hal heard the crash and beckoned to his companions that Lion had the buck down. The two hunters only laughed—in no way could any dog outrun a deer they said. Hal was unsatisfied, however, and spurred his horse toward the commotion. Racing through the trees, he came upon an opening surrounded by poplars and was treated to a spectacle of primal combat.

The fight was thrilling. The buck broke free of Lion’s grip and turned on its haunches. It lowered its head and charged the dog. Lion proved to be too quick, however, and dodged the buck’s attempt to gore him. Lion again jumped on the buck’s back and sank his teeth into its neck. He growled, tore at the muscle and shook his head wildly while the deer thrashed with every bit of strength it could muster, yet Lion refused to relent. Hal approached the animal, pulled his pistol, and fired a shot into the animal’s skull, killing it and effectively ending the chase. Lion had won his quarry.

The two other hunters caught up to Hal just as he was preparing to skin the buck. They motioned him to leave it. They explained that others would be along to collect the kills and bring them to camp. Hal protested, explaining that the deer belonged to him. The hunters disagreed, however, and explained to Hal that since he now part of the band, and since one of the band’s hunters killed the deer, the animal belonged to the whole band. Obliged to follow the rules, Hal left the buck and continued the hunt.

Hal’s Revenge

Being paired with Wacootah allowed Hal to keep a close eye on him. He didn’t entirely trust him, nor did he like him. All through the day, Hal watched closely and waited for a moment when he might break a rule. In the remaining minutes of daylight, Hal spied his new “friend” from a willow thicket just a hundred yards away. The thicket was near the same place Hal was caught the day prior, but this time, it was Wacootah in the wrong. He spied a fine doe about a hundred yards on the wrong side of the river. Temptation was too great. He looked around, saw no one, then stole himself toward the doe. At the report of a fired shot, the deer fell dead. Hastily, Wacootah dragged the animal across the river, which was now frozen over, then attempted to cover his tracks. Hal remained hidden the entire time, watching and making a mental note of what was happening. He would report the scoundrel back at camp and, if all things went well, his hat was sure to be returned.

Sundown came, and the hunting parties returned to camp with their spoils. Wacootah was especially proud of the fine doe he had just felled. As is custom in any hunting camp, the men ate, smoked, shared stories and filled the evening with laughter. Hal was sought after by several other hunters who wished to hear the thrilling tale of the dog taking down the deer—Lion was sure to be the recipient of many head scratches that evening. When it came time for Wacootah to tell his story, however, Hal smirked—it was time to reveal the lie and get his hat back.

Wacootah told of how he spied the doe, how he just barely caught it from the corner of his eye and how he ever so slowly crept within shooting distance and dropped it in its tracks. When asked where the animal was shot, he explained that it was not far, just near the river’s edge.

Hal interrupted the story, in Dakota he explained that the doe wasn’t exactly where Wacootah said it was. Wacootah protested, but Hal persisted, stating that if the rest of the group would follow him to the kill site, they would see that Wacootah was lying. They agreed, and with torches to light their way, set out the short distance with Hal leading the way.

The hunters assembled near the river. Wacootah showed them where the deer laid—the same spot where it was collected after the hunt. Hal, of course, brought the group closer to the river, revealing the drag marks that crossed the river and demonstrating that deer was killed over the forbidden line. Wacootah confessed, apologized to the group, then laid the doe skin at Hal’s feet and asked for forgiveness.

Had he wanted to, Hal could of enacted a severe punishment. Instead, he calmly walked up to Wacootah, grabbed his gun, raised it over his head as if to destroy it, then simply broke the ramrod off inside its sheath which would not render the weapon useless, but would make for a difficult time in retrieving the broken piece. Hal then accepted the doe hide, shook Wacootah’s hand and headed back to camp to ready himself for the next morning’s hunt.

His hat, however, was never returned.

This article originally appeared in the 2023 November December issue of Sporting Classics magazine.