It was the greatest North American hunting trip ever, though the men’s survival was always in doubt.

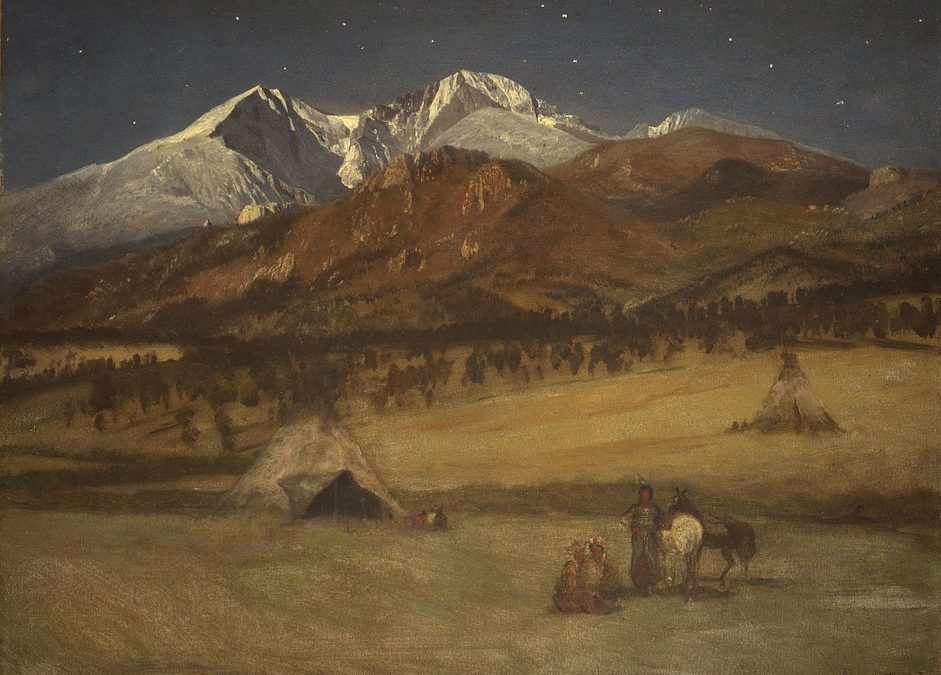

Fall of 1804, Meriwether Lewis was halfway up the Missouri, St. Louis to Great Falls, though he could not name the Great Falls until he had seen them, yet many months away. In the middle of what someday would be North Dakota, Lewis put quill to paper. “The country we passed today was the same as yesterday, beautiful in the extreme.”

The expedition wintered over in Ft. Mandan, a cottonwood log stockade named for hospitable Indians along that stretch of the Big Muddy. Besides Captain Lewis, there was second in command Lieutenant William Clark, 55 men, a Shoshone girl, her Métis common-law husband, their newborn baby and Seaman, a Newfoundland dog. All but the baby and the dog were under commission from the President of the United States.

The expedition wintered over in Ft. Mandan, a cottonwood log stockade named for hospitable Indians along that stretch of the Big Muddy. Besides Captain Lewis, there was second in command Lieutenant William Clark, 55 men, a Shoshone girl, her Métis common-law husband, their newborn baby and Seaman, a Newfoundland dog. All but the baby and the dog were under commission from the President of the United States.

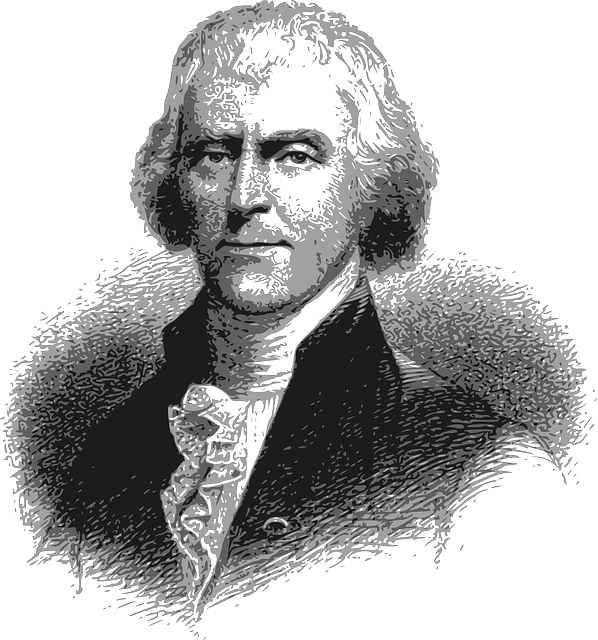

Can you even imagine? In those days it was as daring as a mission to Mars. Jefferson knew the longitude of St. and also the numbers published by Spanish and English seafarers on the Pacific coast, some 1,800 miles to the west. But nobody knew what lay between. Few white men had been even halfway, and those who had, never lived long enough to tell the tale. There was some vague but forlorn hope there might be a clear passage to the riches of the Orient. But the riches they found were more precious than anybody could have predicted.

“The object of your mission is to explore the Missouri River” Jefferson’s handwritten order read, “& such principle stream of it, as, by its course and communication with the waters of the Pacific Ocean, whether the Columbia, Oregon, Colorado, or any other river may offer the most direct & practicable water communication across this continent for the purpose of commerce.”

This “Corps of Discovery” was also to collect specimens — mineral, plant and animal — for the President, a world-renowned naturalist. The orders were simple, but the story is not and it should prick the heart of every hunter, 200-odd years later.

And it almost did not happen. Building boats, gathering volunteers and supplies, Lewis and Clark spent most of 1803 and all of 1804 getting to Ft. Mandan against a backdrop of international intrigue. New Orleans was a Spanish city in those days, a violent backwater, plagued with pirates, prostitutes, sundry cutthroats, awash with tropical disease, itinerent Indians, Africans, Spanish exiles, French exiles, Cajuns, half-breeds, three-quarter breeds, and a collection of international freebooters, increasingly American. Hardly a tourist destination, but it was the only port for American goods coming down the Mississippi.

When the banks failed in 1783 and the treasure ship that was to bail them out was lost at sea with a half-million pieces of eight, the Spanish gave up, ceded the city to the French. Americans, in turn, contemplated its purchase. Jefferson could deal with the Spanish, but nobody wanted to bet on Napoleon Bonaparte, dictator of France.

“The object of your mission is to explore the Missouri River” Jefferson’s handwritten order read.

Jefferson sent James Monroe to Paris with authority to offer ten million for the city and lights to the river. Monroe was entirely blindsided by the French counteroffer: Fifteen million for all of Louisiana, some 827,000 square miles, which would effectively double the size of the United States at the extravagance of three cents per acre, the biggest real estate transaction in the history of the world. It took some fancy footwork with Congress, but Jefferson got it done. Then he sent Lewis and Chark to see what he had just bought. Meanwhile, a Spanish military force, who knew nothing of the deal, left Santaa Fe, with orders to intercept and arrest any trespassers. The Spanish never even got close–700 miles maybe.

Clark drew the maps for the expedition; both men collaborated on the journal. Clark had a steady hand but could not spell. Even in those days before spelling was standardized, he managed to spell Sioux 27 different ways, obviously a record.

Beautiful in the extreme. Living off the land as they went, the Corps of Discovery was the greatest hunting trip ever mounted on this continent, even to this day. Indeed, pushing and pulling a 55-foot keelboat, rowing skiffs, paddling canoes against the swift-running Missouri, or struggling up mountain passes, each man consumed an average of seven to nine pounds of red meat per day, some 33,000 meals over 28 months—nearly a half-million pounds, not counting fish and birds.

The Corps of Discovery carried 15 flintlock rifles for hunting, 15 muskets for defense, two blunderbusses for close combat, one small cannon to terrorize the “savages,” assorted sidearms, fowling pieces and Lewis’ prized .36-caliber squirrel rifle. Powder was packed in watertight lead cans that could be melted down and cast into bullets when empty.

But their most unusual gun was not the cannon, but a .46-caliber Austrian Girandoni air rifle, a 14-shot repeater.

But their most unusual gun was not the cannon, but a .46-caliber Austrian Girandoni air rifle, a 14-shot repeater demonstrated to impress the potentially hostile Sioux. No noise, no smoke, one shot after another? Powerful medicine! And how many of these magic guns did the white strangers have?

Some historians have speculated the Girandoni was the biggest single factor in the expedition’s safe passage. Indeed, only one man was lost, to fever, not hostile natives, and only one Indian was killed, a Blackfoot warrior in the Rocky Mountains, and his tribe held a grudge for generations. But the Indians might not have been so impressed by the Girandoni had they seen the gun being readied. It took hours and 1,500 strokes on a hand pump to fully charge the piece to 850 PSI, wearing out several men in the process.

Come spring thaw, Lewis sent his keel boat downriver to St. Louis. On board were a sergeant and oarsmen, muskets and the cannon, notes from the journal, biological, geological and zoological specimens for the President, with orders to shoot their way through any Indians contesting their passage. The rest of the party continued upriver in canoes and pirogues, greatly disappointing half a dozen Mandan girls who had become very fond of several members of the Corps. Two weeks upriver from Mandan, they were deep in county no white man had ever seen. And they were on their own.

The hunters bagged “partridges,” but did not account them by species, indeed, because they did not know the species. Today we can assume they were sharp-tailed, ruffed and sage grouse, plus pinnated grouse, the prairie chicken. The Corps missed pheasants, of course, as the Chinese cackler was not introduced until 75 years later, on some of the same ground they trod, by the Former U.S. Consul General to Shanghai.

The hunters bagged “partridges,” but did not account them by species, indeed, because they did not know the species. Today we can assume they were sharp-tailed, ruffed and sage grouse, plus pinnated grouse, the prairie chicken. The Corps missed pheasants, of course, as the Chinese cackler was not introduced until 75 years later, on some of the same ground they trod, by the Former U.S. Consul General to Shanghai.

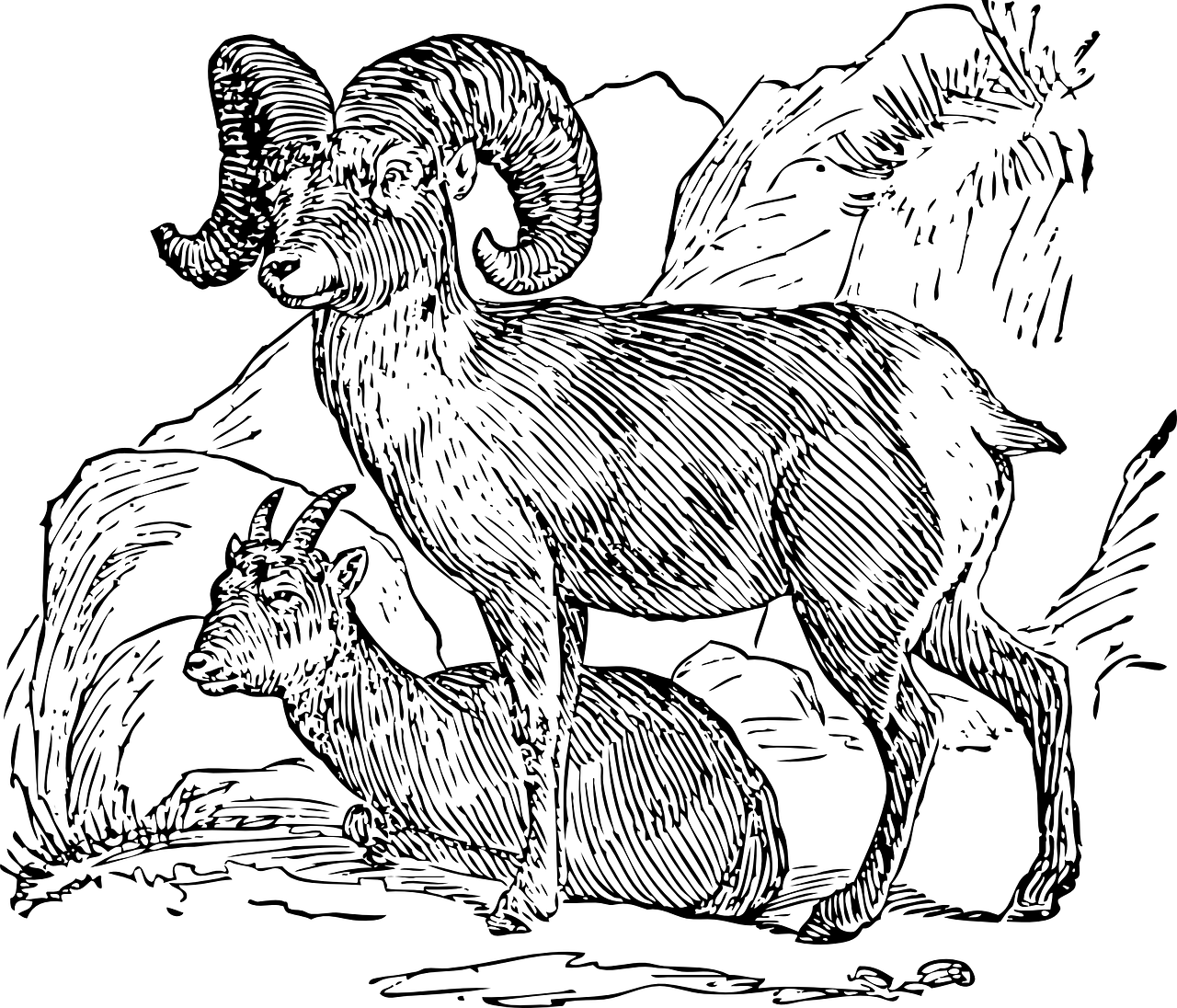

During their expedition, the members dined on ducks and geese, gray and fox squirrels, moose, mule deer, elk, black bear, bison and beaver; broiling the “tender morsels” on sharpened sticks over campfires. They shot and ate species never before encountered by Americans, including pronghon antelope, bighorn sheep, and “the turrible bear;” the grizzly, Ursus horribilis.

Pronghorns were a challenge, as Lewis noted with his cantankerous spelling. “We found the Antelope extreemly shye and watchfull insomuch that we had been unable to get a shot at them; when at rest they generally seelect the most elivated point in the neighbourhood, and as they are watchfull and extreemely quick of sight and their sense of smelling very accut it is almost impossible to approach them within gunshot … they will frequently discover and flee from you at the distance of three miles. I had this day an opportunity of witnessing the agility and the superior fleetness of this anamal which was to me really astonishing. I beheld the rapidity of their flight along the ridge before me it appeared reather the rappid flight of birds than the motion of quadrupeds.”

Clark had better luck on September 14, 1804. “In my walk I Killed a Buck Goat [antelope] of this Countrey, about the height of the Grown Deer, its body Shorter … the Colour is a light gray with black behind its ears down its neck… Verry actively made, has only a pair of hoofs to each foot, his brains on the back of his head, his Norstrals large, his eyes like a Sheep he is more like the Antilope or Gazella of Africa than any other Species of Goat.”

Not being formally trained naturalists and with previous experience limited to eastern North America, neither man could know the pronghorn, Antilocapra americana, is not an antelope at all, but a unique species native to the western plains. Their misnomer stuck and the animal is commonly called “antelope” to this day.

Third in command, Sergeant John Ordway, was directed to keep an alternative journal for back up. On April 3, 1805, Ordway wrote: “Saw a Mountain Sheep on a high Steep bluff on N. S. which had a lamb with it. One man went up the bluff to Shoot them. They took down the bluffs and ran along whare it was nearly Steep where there was a black Stripe in the bluffs. He Shot at them but at too Great a distance. They run untill they got round the bluffs and ran in to the prairie. The coulour of the Sheep was white. Had large crooked horns, & resembled our tame Sheep only much Iarger Size & horns.”

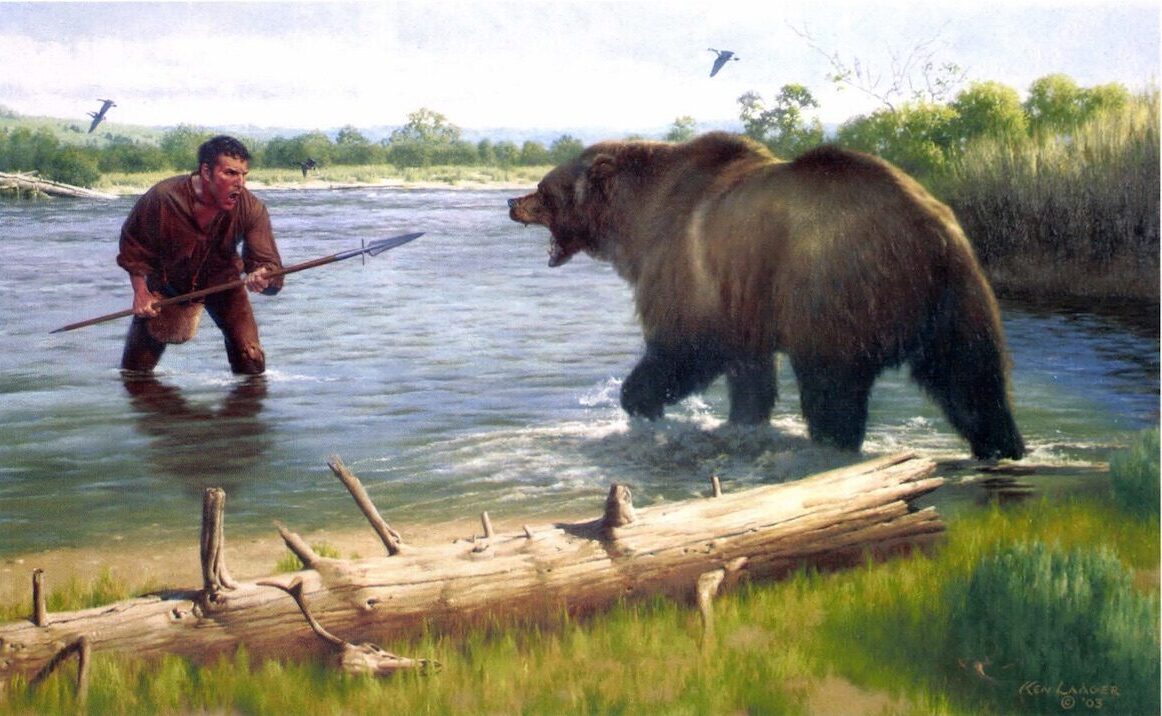

Mandan Indians had given fair warning about “white bears,” saying their hunting parties would not even approach one unless at least ten men strong and even then the bear might kill one or more hunters. Clark dismissed the warnings as coming from indifferent hunters with bows and arrows or maybe cheap trade fusils, but changed his mind quickly on May 5, 1805, when he encountered his first, a 6OO-pound specimen, “a very large and turrible looking animal” that took ten shots to bring down.

Lewis had his own dustup on June 15. He was wandering alone and shot a buffalo, not knowing the buffalo was being stalked by a bear. The bear winded the blood and Lewis raised his rifle, but to his considerable dismay realized he had not yet reloaded. No tree handy and no time to waste, Lewis jumped into the Missouri. The bear splashed after him, but for some reason, abandoned the chase and retreated into the cottonwoods along the bank.

Expedition member Hugh McNeil was scouting alone on horseback when he jumped a grizzly in heavy cover. His horse spooked and threw him nearly atop the now enraged animal. Too close to shoot, McNeil cracked the bear across the nose with his rifle, which gave him enough time to climb a tree. Unlike black bears that can shinny 30 feet in three jumps, grizzlies are poor climbers. There followed a waiting game, the bear trying to shake McNeil loose as he hung on for dear life. The bear lost interest after a couple of harrowing hours and the hunter beat it back to camp. Nobody believed him until he showed them his rifle, the stock cracked nearly in two at the wrist.

From then on, Lewis would not allow his men to venture out alone and ordered every man to sleep with his rifle at the ready in case a griz wandered into camp. Given potentially hostile locals, this was an order long overdue, but it took a bear to get it done.

At the confluence of the Yellowstone and the Missouri, Lewis mused he had better stop writing about all the game or nobody would believe him. He reckoned the country he’d crossed to be so vast it would take a hundred generations to populate, when it only took 80 years. In 1893, when the population of the West had risen to an average of three persons per square mile, the Department of the Interior proclaimed the frontier closed.

Back at Ft. Mandan, on the expedition’s return trip in 1806, one man looked wistfully over his shoulder and asked to be dismissed. Seeing what he had seen, there was no way he could ever live a civilized life again. His request was granted. He gathered provisions, turned around, and headed back upstream. He was John Coulter, the very first American mountain man.

Lewis and Clark were hailed as heroes wherever they went and both were awarded government jobs. William Clark became governor of Missouri and Chief Indian Agent. He married a Virginia girl, fathered five children and died happy at 68, a respectable age in those days. Others did not fare so well. Lewis was elected governor of the Louisiana territory but never lived to see the publication of the expedition’s journals. He met a violent end just a few years later, in a lice-infested roadhouse along the Natchez Trace, shot twice and cut three ways, high, wide, and frequent. He was alone with the innkeeper’s wife and to this day nobody knows for sure what happened. Was it suicide, sexual murder or political assassination? Clark thought Lewis killed himself — “the burden of his mind was too great.” A modern DNA test found the blood of three individuals on his Masonic apron but requests by the family to exhume his remains have been nixed by the National Park Service, custodian of the grave.

The Shoshone girl died in the Missouri Territory of “a putrid fever” just before Christmas 1812. William Clark adopted her two children. One of the expedition’s enlisted men published his own journal and made money from it, but incurred the wrath of his former commanding officers. Sergeant Ordway’s account, the alternative journal, was lost and unpublished until 1912.

The names and the fates of most of the others have been lost in history’s eternal shade. But say a prayer for them, light a candle, raise a glass of good whiskey around a campfire. They gave us the Great Plains, the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific Northwest, some of the best hunting on earth.

An extraordinary collection of fifteen stories that celebrate America’s unquenchable thirst for excitement.

An extraordinary collection of fifteen stories that celebrate America’s unquenchable thirst for excitement.

Great American Adventure Stories contains page-turning accounts of the Galveston Hurricane, the Alaska Gold Rush, a robbery featuring Jesse James, an eyewitness account of the Johnstown flood, and much more. For a taste of the American frontier, Daniel Boone and famed scout Kit Carson depict what they saw and experienced as the country expanded and blossomed in the West. These accounts all have one thing in common: They capture the grit and spirit of people who made America what it is today.

Created for adventure addicts there has never been a more exciting collection of stories that celebrate the indomitable spirit of the American character. Buy Now