“Hurry and shoot before he runs away,” urged Totze.

“Yes, hurry,” added Bawlo. “He’s a wonderful trophy, and if he gets away we’ll never find another half as big.”

Even grizzled old Malkopje joined in.

“Ah, look at those horns, the biggest buffalo I’ve ever seen in my life.”

I didn’t know it at the time, but I was the beneficiary of an African con job. It probably would have worked too, except the trio of African trackers crouched behind me were jabbering in a bush lingo as strange to me as my language was to them.

The object of their urgent encouragement was a big Cape buffalo standing in the midst of three smaller bulls some 80 yards away. All had their heads up and muzzles leveled at us like a quartet of heavy artillery.

The bull was big, no question, by far the biggest I’d seen in six days of on-and-off hunting. He was also very old, nearing the end of his years, so old that almost all the hair was gone from his grayish-black hide, leaving his shoulders like granite boulders. His horns were craggy and worn with age, but even so they out-spanned those of his companions by several inches. This, I figured, was the one I’d been looking for, but before pulling the trigger, I wanted an opinion from Lew Games, my professional hunter.

“What do you think?”

“He’s pretty good,” Lew answered, “but I think we might find something a bit better.”

Which was all I needed to hear, so I dropped the big .458 Magnum from my shoulder to the accompaniment of a chorus of groaning disappointment from the three trackers.

“What’s wrong with this fellow?” they lamented. “We find the biggest bull in the world and he doesn’t shoot!”

Back at the truck, a laughing Lew supplied me with a translation of the trackers’ comments and also explained the reason for their disappointment.

Africans have a well-founded fear of the Cape buffalo, and their idea of a shootable buffalo is one that can be bagged with as little risk to life and limb as possible. The buffalo I’d just passed up had been situated on fine running ground and hadn’t been too far from the truck. If anything had gone wrong, the trackers would have had a good chance of making it back to the safety of the vehicle. Plus, the fact that the surrounding vegetation was sparse enough meant that tracking a wounded animal would have been relatively safe and easy. Which, basically, is why they had been so much in favor of my shooting the bull.

Thinking it over, I was much inclined to share their point of view, because only a couple hours earlier we’d narrowly escaped what could have been a showdown with a vengeful buffalo cow.

To my notion, the Cape buffalo is the real nitty-gritty of African hunting. I’ve long been fascinated by the huge black beast with tremendous horns and terrible temper. Weighing close to a ton and born with a vengeful nature, the Cape buffalo has a well-earned reputation for being able to absorb a magazine full of thumb-sized bullets and still have enough meanness left to grind his adversary into the ground.

According to accounts I’ve read, and stories I’ve heard from survivors firsthand, a favorite tactic of wounded buffalo is to escape into dense cover, then circle back to ambush his pursuers. Memories of which had resurfaced throughout the morning when I found myself almost at the center of a buffalo herd, at moments so close that I could have hit them with a tossed stone. At one point I had even put the crosshairs of my heavy rifle on a bull and came within a whisker of pulling the trigger.

We had started out just after daybreak from our camp near the edge of Botswana’s Chobe swamp and planned to hunt west along the Kwando River. It was my first African safari, and in less than a week I’d already seen more game and had more adventure than I’d ever dreamed of.

I’d been named shooting editor of Outdoor Life a couple years before, and ever since signing on I’d been dropping hints to Bill Rae, my boss, that he needed to send me to Africa to do some “field testing” with a few rifles and some of the exotic-looking new generation bullets I’d hand-load for them. Rae, who ruled the magazine like an Olympic deity, finally agreed that the African experience would probably do me some good, and seeing as how hunting adventure articles always sold well, sent me on my way with orders to find something interesting to write about and take lots of photos.

“Focus your camera and hold it still,” had been his parting instructions. By the end of just this first week of a month-long safari, I’d already bagged enough game and taken enough pictures to fill the magazine for a year. And I still had a buffalo license to fill.

We’d been seeing buffalo every day, but they had either not measured up to what I was hoping for or had disappeared before we could get near enough for a close look. Which is why we were headed for the Kwando and a change of scenery. Lew had done some scouting there during the previous season and thought it would be a likely area to find bigger horns than we’d been seeing. There was a chance we’d see sable antelope, which I had a license for.

The road to the Kwando, as Lew remembered from his last trip there, was little more than an uneven, untraveled track, and it would probably take us better than an hour to get to the river. So we took along lunch and extra water, and I was looking forward to making a day of it, especially since no other hunters had been in the area since the year before, and I’d be having a first look at the game.

As it turned out, we never made it to the river.

About a half-hour along the way, while skirting the edges of the swamp, we came to a wide stretch in the road where the crust of its hard-baked dirt surface had been ground to powder by the hooves of passing buffalo. Judging by the width of their trail, and the numbers of overlapping tracks, it had been a good-sized herd, possibly 50 or more, and they had crossed only a short time before. So recently, in fact, that the pall of powdery dust still hung in the cool morning air. Obviously, they had watered at the swamp and had crossed the road on the way back to their home grounds.

We immediately abandoned our plans for the Kwando, because a herd of that size would very likely include some good bulls. So, with my .458 Magnum rifle in hand, we set off after them.

Their trail led away from the swamp’s dense green foliage into a more open landscape of tawny-colored grass and Botswana’s ubiquitous scrub of brushy mopane trees. Though shoulder high in some places, the brittle, winter-dried grass was easy to pass through, so we made good time and within a couple miles caught up with the herd, which had stopped and scattered out between patches of mopane. Most of them had bedded down and the high grass made it difficult to see, but here and there we could make out the outlines of their reclining hulks.

This was not exactly an ideal situation, but Lew figured that the tall grass and scattered trees would give us enough cover to tippy-toe around the herd and see if any big bulls were in residence. Performing a ritual I had witnessed many times over the preceding days, Lew pointed at his foot and shuffled the toe of his shoe into the dry ground. A small cloud of dust rose and then lazily settled from where it had risen. There was no wind, meaning we might get even closer to the animals without being detected. But the prospect of getting close to a herd this size reminded me of something Lew had warned me about just the day before.

A herd of buffalo can be utterly unpredictable, he had said, and like most cattle they are quite curious. It is their curiosity that can be the undoing of an unsuspecting hunter.

When a herd spots an unfamiliar creature, such as a human, they have a natural tendency to stop and stare. The buffalo at the rear of the herd want to have a look too, so they begin to push and crowd toward the buffalo at the front. This shoving from behind pushes the front ranks toward whatever they are watching and can cause them to panic. And when they panic they are liable to stampede, and whatever or whoever happens to be in their way will probably be the worst for it.

A Cape buffalo is a dangerous adversary, much less a whole herd of the angry beasts. (Photo: TellMeMore5000/iStock)

This bit of information had made quite an impression on me, and I had resolved at the time to never get involved with any curious buffs. Yet here I was at the edge of a herd, and of my own free will, about to get very much involved.

When we’d slipped to within a hundred yards or so of the closest animals, Lew instructed Bawlo and Malkopje to stay behind, because the buffalo would be more likely to spot the five of us if we stayed together. The two Africans enthusiastically agreed, but Totze didn’t appear the least bit happy about Lew’s directive, and even less so when Lew handed him his rifle, indicating that, as gunbearer, he would be in the thick of whatever ensued.

Totze was not one of our original crew and had simply appeared at our camp three days earlier, seemingly out of nowhere. Almost naked except for a string of crude ornaments hanging from his neck along with equally rough bands on each arm, he’d been squatting at the camp’s perimeter when I spotted him on the first morning of our hunt. Apparently he was uncertain if he would be welcome in our camp and was waiting for some signal as to whether or not to come closer.

The odd-looking stranger was still there when we returned later that afternoon, looking like he had not moved from the same spot. When Lew drove close to him and stopped, I instantly recognized the man as a member of a fascinating race I’d read about, but never thought I’d see face to face. Standing scarcely five feet, crowned with peppercorn hair, and with almost oriental facial features, the man was unmistakably a Bushman, the distinctive race known for uncanny survival in the harshest environments such as their Kalahari homeland, and for their almost mystical tracking skills.

Speaking in a language punctuated by odd tongue-clicking, Lew and the bushman had a short exchange, after which the newcomer followed us into camp. After hanging around for a couple days, the bushman decided life there was pretty good, no doubt immensely better than wherever he’d come from, and the evening before had come to our campfire appealing to hire on as a tracker. After considerable discussion in the Bushman’s peculiar language, then more in another language, Lew agreed to give him a try, explaining to me that good trackers are always valuable, especially one possessing the skills for which Bushmen are legendary.

His name was Totze, Lew said, and he thought he understood the local languages well enough to follow orders and get along peacefully with everyone. I had already noticed that several of the staff regarded him as something of a curiosity and had even provided him with some ragged clothes.

Which is how Totze came to be hunting with us on his first day after being hired, and why I was surprised when Lew handed him his rifle, a job usually reserved for the most reliable assistants. His purpose, I decided, was to test the little Bushman’s skills and staying powers. There couldn’t have been a more ideal circumstance in which to do so, as I would soon discover.

By snaking through the grass and taking advantage of the scattered clumps of mopane, we worked our way closer to the herd than I would ever have guessed possible. The buffs were divided into groups of threes and fours, and Lew’s technique was to slip to within 50 yards or so of each lounging group and check for big bulls. Sometimes a head would be turned so we couldn’t see the horns and we’d have to wait a few minutes for the buff to move its head. Then we’d sneak off and find another bunch.

There wasn’t a breath of air stirring. If there had been, our quarry would have surely caught our scent and become too wary—and dangerous—for us to get as close as we were. Before sneaking from one brushy concealment to the next, Lew or I would test the air by sifting a handful of the powdery Botswana soil between our fingers, but there was never a hint of a current that might carry our scent to suspicious noses.

Gradually we worked our way so close to the center of the herd that dark shapes loomed all around us and I could even hear their bellies rumble as they belched up hunks of cud. Once, just as we had slipped through an opening in the brush, we found ourselves only a dozen feet from an old cow on her feet and looking straight at us. She studied our frozen forms for a few long moments and must have decided that we were part of the foliage because she went back to chewing her cud and flicking her ears at the flies. We had been standing so motionless that a bird landed no more than ten inches from Lew’s face and gave him a good looking over.

Each time we stopped to check out a batch of heads, Totze would squat down close to my legs in a huddle of trembling flesh so tiny that I could have almost cover him with my two hands. He was obviously terrified of the nearby buffalo, but stayed right with us, maintaining a death grip on Lew’s rifle all the while. Every time we moved, he would be right on my heels, watching my every move, his eyes shifting from me to my rifle and back again. His behavior struck me as rather peculiar, and I made a mental note to ask Lew about it later.

On the first day of my safari, I had made it clear that no matter how many reliable gunbearers we had on hand, I would carry my own rifle at all times. The main reason being the stories I’d heard and read about hunters who had been left to face dangerous game empty-handed because their gunbearers had run away with their rifle. Now, with dozens of buffalo all around us, I was feeling doubly righteous for having pledged to do my own gun-toting. I also had a camera strapped around my neck, and probably could have taken some great shots of buffalo, but I was afraid the shutter click might spook them. We were that close!

Cautiously zigzagging through the mopane scrub, we had checked quite a few heads but had spotted nothing but cows and calves and a few smallish bulls. If there were bigger bulls in the herd, they had to be off by themselves where we couldn’t see them. We were wasting our time, not to mention risking our necks pussyfooting around cows with calves, which can be every bit as dangerous as bulls.

Then, just as we were backtracking out of harm’s way, a serious situation presented itself in the form of a little black calf. We had noticed it frisking about earlier, but it had been about 40 yards away and no particular cause for concern. But now it had suddenly taken an interest in the clump of brush where we were and came trotting over for a closer look. When he spotted us, he skidded to a stop and stood there no more than 15 feet away, twitching his nose and trying to figure out what we were. After a few moments of this standoff, his momma, some distance behind, got curious too and heaved herself to her feet.

This, I figured, was it—the old gal was going to come over for a closer look and probably decide that we were picking on her kid. Remembering what Lew had told me the day before, I had visions of a buffalo stampede with us caught in the middle.

For the moment, our only defense was to remain absolutely motionless and hope the little bugger didn’t bellow for his mom. After a few breathless minutes the calf lost interest in us and scampered off to join his playmates. His mother took a final long look our way, then lay down again.

I breathed a long sigh of relief, and I think Lew did too. Totze never took his eyes off me.

Doubling back the way we had come, we picked up Bawlo and Malkopje and made a wider circle around the herd to look for any isolated bulls.

While we were taking a short break, Totze gave his fellow trackers an animated account of his adventure among the buffalo, with special emphasis on his coolness in the face of imminent danger, with a chuckling Lew providing a translation of the narrative. Which reminded me to ask Lew why the little Bushman had followed so close and eyed me so strangely, which for several minutes he couldn’t answer for being choked up with laughter.

“Damn, I guess I forgot to tell you, Jim, but I told Totze you would shoot him with your elephant gun if he ran away with my rifle. He must have been convinced you would do it.”

The only bulls we found on our circuit around the main herd were the four with the bigger bull that our trackers had tried to con me into shooting. So after leaving the old guy to spend the rest of his days in peace, we went back to the truck and resumed our trip to the Kwando. It was past noon by then, and after the morning’s hours of creeping among the buffalo, I was looking forward to a peaceful lunch along the river’s cool banks.

Along the way the narrow road left the open grass plain and meandered into denser riverside growth. Rounding a copse of trees, we almost ran into a band of four bulls standing right in the road! They looked like big ones with good horns, but before we could get a better view, they charged into thick cover toward the river, snorting and wringing their tails over their backs.

Lew, thinking fast, hit the gas and we raced down the road, then stopped out of sight from where the bulls had been. Grabbing our rifles, we ran toward the thick woods, which would provide enough cover for us to get a closer look and possibly even a shot. But it didn’t work out that way, because when we spotted the bulls again, they were 80 yards away, headed back to where we’d first seen them. The animals were ambling across mostly open ground with scattered clumps of waist-high grass. To get closer we would have to cross part of the open area in full sight of the bulls.

“If we’re lucky, they might let us get close enough for a good look,” Lew whispered. “But even if they spook and run, we won’t be any worse off than we are right now.”

“Let’s go take a look,” I whispered back, trying to sound casual, even though my heart felt like it was banging its way out of my chest.

Motioning for the three trackers to stay back out of sight, Lew took his .458 and, with me close behind, we approached the bulls at an angle so as to appear to be headed somewhere other than in their direction. Walking fast and bent over with our heads down, the tactic worked, and when we’d shortened the distance to about 70 yards, we stopped and straightened up enough to see over the grass.

The buffalo knew we were there because they were looking straight at us, nervously flicking their tails as if undecided what to do. Standing before us were three trophy-sized heads, all bigger than the bull I’d refused earlier. One, however, made his companions look like a bunch of boys. His horns swept down to his jaw line, then curved out and upward in a tremendous arc, forming a symmetrical circle so nearly complete that the tips pointed back at his massive head. His wide boss spread over his head like a helmet of black armor. There was no need to ask Lew about this one; he was one for the record books—the trophy of a lifetime.

My fantasy of 30 years was suddenly becoming reality. The flood of memories must have caused me to hesitate; I don’t know how long I hesitated, an instant perhaps, but long enough for the bull to wheel and charge back into the denser river vegetation.

Gone.

My heart was sinking, but there was still a chance for a fine trophy—and a great adventure story for the magazine—if any of the other bulls would stay for a moment. They thrashed around for a moment, acting like they were about to run but then settled down and resumed looking at us, their curiosity overcoming their natural instinct to escape. But I knew they wouldn’t stay long, and if I was going to get a shot, I’d have to make a quick choice and shoot.

Scanning the bulls through the low-power scope on my rifle, I could see no difference between them and had settled the crosshairs on the closest bull when Lew grabbed my arm.

“Hold it! The big one’s coming back . . . there he is.”

Off to our left, the bull stepped through the trees to where I could see his head, then his shoulders, and finally nearly half of his body. And then he stopped, looking straight at us.

Would he come out farther? I didn’t care.

I’d hesitated too long before, but not this time. At the roar of my big rifle, all of the bulls spun and charged back toward the river, crashing out of sight through the wall of trees. My bull disappeared even before I could cycle the bolt of my rifle, so there was no way I could hit him again.

Damn! Had I wounded a buffalo? All I knew was that he wasn’t where he was when I shot and was now lost somewhere in heavy cover.

“Lew, I called the shot good,” was all I could think of to say, certain that the crosshairs had been on target before the rifle recoiled, hoping he’d seen the bullet hit and the animal react before disappearing. The answer I hoped for did not come.

Seeing what had happened, the trackers came on the run and gathered around Lew who, gesturing toward where the bull had disappeared, quietly gave them an analysis of the situation and a plan of action.

Though I could not understand the natives’ language, I clearly knew what he was explaining to the three serious-faced men, just as I also understood the meaning of solemn nods of understanding from each of them. They had a job to do and they knew it. I understood the purpose of their standing quietly for long moments with hands cupped behind their ears and facing where they thought the buffalo might be. They were hoping to hear a clue—the groaning bellow of a dying buffalo perhaps. I cupped my ears too, desperately listening, but the only sounds were the distant cries of river birds.

Shaking their heads, the trackers indicated they heard nothing. The buffalo might be dead, but he might also be waiting for us, and there wasn’t anything to do but go in after him.

I had heard about similar situations where the PHs have requested, even ordered, their hunters to stay behind and out of the way. Lew made no such suggestion, and even if he had, I would have refused. When I’d told him my shot looked good, he had seemed satisfied that it had been. But as the five of us moved closer to the trees where a wounded buffalo might be waiting, my confidence plummeted. The shot had looked good, and I was confident it was.

But had I shot too fast, before I could see all of the buffalo? Should I have waited for a better angle? Would it have been wiser to shoot one of the closer buffalo? Either way, no point in second-guessing myself; I had done what I’d done and right or wrong I would live with it.

Such doubts were erased seconds later with a loud yelp from one of the trackers, followed by an even louder shout from another, and then all three waving their arms. A grinning Malkopje pointed to blood splotches on the side of a tree and then another tree even more spattered with red. Beyond the trees lay a wide trail of blood-sprayed vegetation that ended at the unmoving form of my buffalo.

It looked very dead, but then, dead buffalo have been known to get up and charge. Lew and I made a wide circle around the animal and cautiously approached its head until we were close enough for Lew to touch its eye with the muzzle of his outreached rifle.

Nothing, no reaction. It was truly dead.

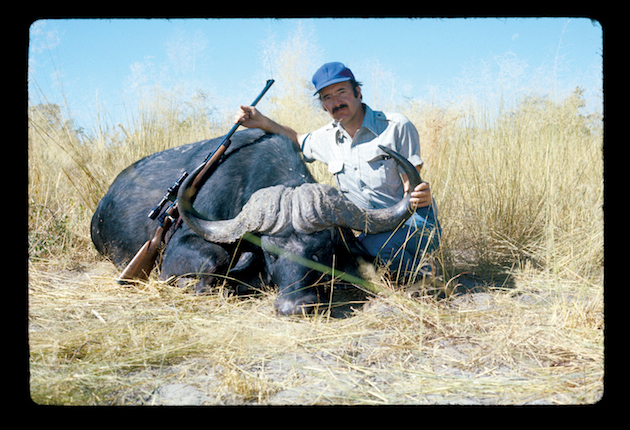

The author’s buff, a trophy for the ages. (Photo: Jim Carmichel)

The heavy solid bullet had gone completely through his chest and he had died in seconds, but enough time for the tough animal to spin around and run nearly 20 yards. Now there were black hands grabbing mine, rejoicing and laughter, joyous relief from the fears and tensions of only minutes before.

Then it was time to go about the other business I had come for, taking pictures for what would be my Outdoor Life story about this incredible day. My cameras were sent for, and as I was posing with the three trackers around the buffalo, a happily smiling old Malkopje made a brief comment to his companions that prompted their enthusiastic agreement. Whatever he said caused Lew to laugh, and I asked what was so funny, especially since I figured it was something about me.

“They are saying you should be happy they didn’t let you kill that bull you wanted to shoot this morning, because they all knew it was much too small,” he explained.

Classic Carmichel

This exciting adventure is among 31 chapters in Classic Carmichel, a fascinating new book by longtime Outdoor Life Shooting Editor Jim Carmichel. Published by Sporting Classics, the book presents nearly 400 pages of hunting adventures from Alaska to Africa, Russia to New Zealand. Recognized as one of the world’s foremost authorities on sporting firearms, the author shares his incredible expertise and experience in a number of fascinating stories on guns and shooting.

Complementing these stories are some 50 full-color photographs that have never been published. Classic Carmichel is available in a hardcover Collector’s Edition for $50 and in a Deluxe, signed, leather-bound edition of 350 copies for $75. Copies can be ordered here, or call (800) 849-1004.