There’s a line in the film You’ve Got Mail in which Meg Ryan’s character laments the closing of her mother’s New York City book shop. She says that someone will probably call the closure a testament to the city, how it’s always changing into something new and never stagnating. But what is actually happening is a part of the character is dying, and the store will soon become something tacky, like a Baby Gap.

There isn’t a Baby Gap popping up on Theodore Roosevelt’s famed Elkhorn Ranch, but the site is changing, and not for the better. A gravel mine is up and running within a mile of TR’s former abode on the North Dakota Badlands. With the new operation comes significant changes to the land, and a property steeped in hunting lore will never again be surrounded by the untainted beauty our 26th president held so dear.

The Salt Lake Tribune published the story Tuesday to the sadness of many readers of Roosevelt. The mine is 25 miles in scope and owned by a Montana businessman named Roger Lothspeich. It began operating the same day on a U.S. Forest Service-owned ranch that lies next to the Elkhorn. While the federal government owns the land, Lothspeich owns the mineral rights.

The government bought the ranch in 2007 at the urging of more than 50 organizations — including Roosevelt’s brainchild, the Boone and Crockett Club — for the tidy sum of $5.7 million. Lothspeich protested, saying he owned the mineral rights to the land. He offered to sell the rights back to the U.S. or to the environmental groups against his proposed mining, but would not relinquish his claim.

An eight-year legal battle ensued, with the two sides coming close to a settlement three years ago. The government offered to transfer Lothspeich’s mineral rights to another piece of land in place of the North Dakota ranch or exchange it for another piece of land, which he accepted. He signed the agreement with the Forest Service, but when the feds didn’t move fast enough for him, he decided to move ahead with the mining operation anyway.

The Tribune wrote that Lothspeich “decided to mine gravel at the site instead to take advantage of a growing need for roads and other projects in North Dakota’s oil patch.”

His proposed operation reportedly posed no significant impacts to the area, so the Forest Service gave his mine final approval Monday; crews began digging the next day. According to Forest Service district ranger Shannon Boehm, Lothspeich’s mine has all the valid permits needed to operate.

The Chicago-based Environmental Law and Policy Center has filed a lawsuit to challenge the Forest Service’s approval, but the mine will likely continue its operations.

No work is being done on the Roosevelt ranch, but the next round of Google Earth satellite photos will certainly show a disparity between the neighboring properties. What is truly newsworthy for fans of Roosevelt is not the loss of the Elkhorn’s neighbor, but the loss of the wildness that captured TR’s heart in the first place. The 21st century is encroaching on the idyllic hunting locale, and despite Roosevelt’s work to protect millions of American acres from over-development and destruction elsewhere, his own ranch now sits at the doorstep to modern mining practices.

Roosevelt first came to the Badlands in 1883 to escape the heartbreak of his first wife’s passing in New York. He established two ranches: the Maltese Cross in 1883, and the Elkhorn in 1884. The Elkhorn was named, unsurprisingly, for two sets of antlers he found locked together in the area.

The Elkhorn quickly became his primary home on the range, with some historians believing he even had a darkroom in the cellar for photography — an unheard of thing for anyone at the time. The Little Missouri flowed within 150 yards of his doorstep, the river bottom of which he pursued whitetails in when not hunting away from the ranch for bigger game.

Today the Elkhorn lies 35 miles north of the village of Medora. Once much larger, it now encompasses 218 acres of Theodore Roosevelt National Park. All that remains of the original 60-by-30-foot lodge are the foundational cornerstones, along with the marked water well nearby. Several cottonwood trees on the site were alive a century ago when Roosevelt walked the land.

Surprisingly, he never owned any of the land the ranch sat on or even an acre of the prairie his cattle grazed. The Theodore Roosevelt Center remembers him as a typical-of-the-time squatter on public domain land and land granted to the Northern Pacific Railroad. In some ways, that’s even more picturesque of the then-future president. He lived a working-man’s life on land shared by all working men.

Several of his writings chronicled his time on the Badlands and at Elkhorn, including Hunting Trips of a Ranchman and The Wilderness Hunter. In Hunting Trips, Roosevelt described the ranch as follows:

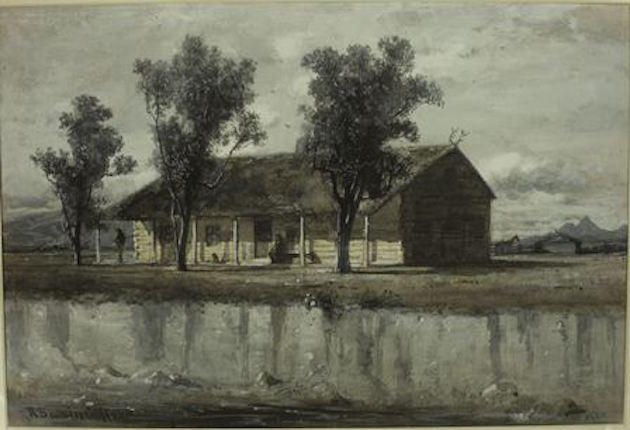

My home ranch-house stands on the river brink. From the low, long veranda, shaded by leafy cottonwoods, one looks across sand bars and shallows to a strip of meadowland, behind which rises a line of sheer cliffs and grassy plateaus. This veranda is a pleasant place in the summer evenings when a cool breeze stirs along the river and blows in the faces of the tired men, who loll back in their rocking-chairs (what true American does not enjoy a rocking-chair?), book in hand — though they do not often read the books, but rock gently to and fro, gazing sleepily out at the weird-looking buttes opposite, until their sharp outlines grow indistinct and purple in the after-glow of the sunset.

The story-high house of hewn logs is clean and neat, with many rooms, so that one can be alone if one wishes to. The nights in summer are cool and pleasant, and there are plenty of bear skins and buffalo robes, trophies of our own skill, with which to bid defiance to the bitter cold of winter. In summer time we are not much within doors, for we rise before dawn and work hard enough to be willing to go to bed soon after nightfall. The long winter evenings are spent sitting round the hearthstone, while the pine logs roar and crackle, and the men play checkers or chess, in the fire light. The rifles stand in the corners of the room or rest across the elk antlers which jut out from over the fireplace. From the deer horns ranged along the walls and thrust into the beams and rafters hang heavy overcoats of wolf-skin or coon-skin, and otter-fur or beaver-fur caps and gauntlets. Rough board shelves hold a number of books, without which some of the evenings would be long indeed.

The idyllic hunting home is down to its foundations. Now, with the opening of the mine, much of the picturesque scenery once seen from the veranda will likely disappear as well. The Badlands have certainly changed around Elkhorn over the last century, but always at a distance. Roosevelt’s ranch remained an oasis in the modern day, taking hunters and all those who wish to have lived in Roosevelt’s era back in time in a way. While Roosevelt’s actual ranch is still protected, and though the mining is legal and lawful, it’s a sad day when modernity rides so close to where such a great hunter once rode his horse. The former wildness of the Badlands now lives only in Roosevelt’s writings.