In the 60s it was hip to be bass, and anglers everywhere welcomed a whole new breed of American hero.

By 1965, the bassing revolution was at full throttle and re-born bass fishing was rapidly becoming galaxial. It was hip to be bass. Popularity encouraged fraternity and pride prompted friendly prejudice. Erupting into fierce competition, it fired the attention of the national media, ordered a national belonging, and provoked an already burgeoning ingenuity to fantastic heights. Fame followed fortune, and by the end of the decade, even the dreamers were overwhelmed.

Here’s the final six of the most revered products and events of the 60s — arguably the most portentous — the phenomena, above all others, that would bring recognition, gloss and glory to modern bassing.

Skeeter & Ranger Boats

The quest for an icon to best symbolize new age bassing would be brief, almost pre-acclaimed. The charismatic profile of the low-slung sled with double jump-seats and a monster outboard has fixed the bass boat almost as firmly in national fancy as the prairie schooner. As the covered wagon and the railroad opened the West, the bass boat gave fishermen supremacy over big water and a manifest identity. No single person nor concern can begin to claim sole credit for the configuration. It arose like a patchwork quilt. and many of the contributors are ow as obscure as backyard ingenuity. As the commercial image and availability of the bass boat emerged in the 60s, however, two names became legendary: Skeeter and Ranger. Neither can be fairly mentioned in absence of the other.

The quest for an icon to best symbolize new age bassing would be brief, almost pre-acclaimed. The charismatic profile of the low-slung sled with double jump-seats and a monster outboard has fixed the bass boat almost as firmly in national fancy as the prairie schooner. As the covered wagon and the railroad opened the West, the bass boat gave fishermen supremacy over big water and a manifest identity. No single person nor concern can begin to claim sole credit for the configuration. It arose like a patchwork quilt. and many of the contributors are ow as obscure as backyard ingenuity. As the commercial image and availability of the bass boat emerged in the 60s, however, two names became legendary: Skeeter and Ranger. Neither can be fairly mentioned in absence of the other.

In 1948, a Shreveport. Louisiana, bass addict by the name of Homes Thermon developed a bulge-sided, canoe-type boat with a needle-like nose which suggested its name: Skeeter. Stable and shallow of draft, it was designed to probe backwater pockets. Thermon later marketed the Skeeter in Marshall, Texas. His friend. Russell Reeves, now 83 and the most venerable Skeeter dealer in the nation, gave it commercial life. A Reeves co-worker, Jimmy Dockery, meantime, came up with slick-steering from the bow.

In 1960, the Skeeter was offered as a pre-packaged rig, in wood or glass, with a trolling motor, sit-down seats, “Jim-Stick” steering, a7.5 Martin and a trailer. “A novel concept for the times,” observes Tom Zenanko, present-day Skeeter Marketing Manager, “an early forerunner of today’s packaged bass rigs.”

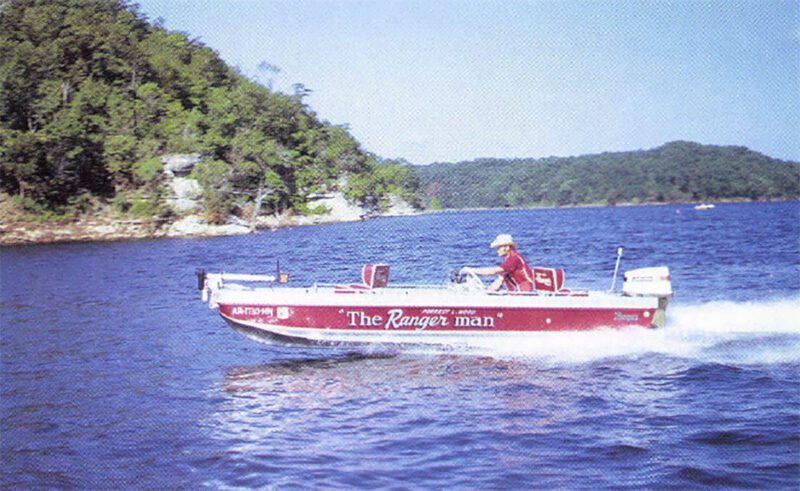

By 1965 the Skeeter line included a new series of fiberglass tri-hulls, destined for immediate success: the Skeeter Hawk, Sweet Thing and Super Skeeter. The Super Skeeter is the foundation boat for the modem Skeeter, and occasionally you find one in service on Texas waters even today. The Hawk was an elongated 16-foot lapstrake that could take a lot of water, and bass fishermen began customizing it for the purpose. In 1969, when Ranger was finding its water-legs commercially, the Skeeter Hawk was perhaps the most popular “pro-type” boat going, with a jaw-dropping, big-horse Merc or Chrysler clamped to the stern. Long, lanky Forest Wood grew up in the Ozarks, in hard times, doing what was necessary to piece together a livelihood. “You had to shoot what got up,” he likes to say.

Part of “what got up” was fishing, and Forest guided for trout and smallmouth on Crooked Creek, the White River and other local streams. After Bull Shoals came in, his wife, Nina, brother Mickey and the whole Wood family were involved. Forest was always fishing with his knees stuck up in his chest, so he started tailoring a boat or two for comfort, which resulted in a fiber glassed riverboat with raised fishing seats. Local folks admired them and with Mickey, Wood began building a few for sale. From the beginning, customers could help design their own. In the middle 60s Forest began competing in bass tournaments, accepting a few boat orders on the side, and Ranger was born.

Part of “what got up” was fishing, and Forest guided for trout and smallmouth on Crooked Creek, the White River and other local streams. After Bull Shoals came in, his wife, Nina, brother Mickey and the whole Wood family were involved. Forest was always fishing with his knees stuck up in his chest, so he started tailoring a boat or two for comfort, which resulted in a fiber glassed riverboat with raised fishing seats. Local folks admired them and with Mickey, Wood began building a few for sale. From the beginning, customers could help design their own. In the middle 60s Forest began competing in bass tournaments, accepting a few boat orders on the side, and Ranger was born.

“He’d come back with two or three customer drawings,” Mickey recalls, “often on a table napkin or a paper bag, and we’d go from there. “Forest and Mickey built a modest total of six “R” series Rangers in 1968, but demand would soon outstrip all imagination. Aroused bass “pros” were clamoring for a hull that could handle rough water and big engines “The first time a customer hung a 60-horse on one of our boats, I thought for sure he would kill himself,” says Mickey.

Ranger responded with the “tournament-weight” TR Series, which by 1970 was rapidly establishing the unmistakable profile of the modern bass boat. As one period observer fondly put it, “an early TR with a stacked-six, 115 Merc looked like a canoe with a smokestack.”

Coming out of the 60s, Skeeter faltered for a time, caught in Ranger’s backwash, then surged again. Today, as yesterday, among the bass elite, Ranger and Skeeter still occupy the pinnacle Ranger has remained the official boat of the B.A.S.S. Masters Classic since its beginning in 1971.

B.A.S.S. and the BASSMASTER Tournament Trail

By 1968, big-water bass fishing was riding an ascending star. Never had there been such a wealth of fantastically productive water, nor greater intrigue in its mastery Appellations such as Eufaula, Seminole and Ouachita were uttered like evening vespers, “pattern,” “structure” and “holding cover” were part of an elite new mantra, fresh products hit the sporting counters almost weekly, and the excitement was as infectious as measles. Bass fishermen were gathering spiritually, akin to folks at a Wednesday-night tent revival…ready for religion, but waiting for the right sermon.

By 1968, big-water bass fishing was riding an ascending star. Never had there been such a wealth of fantastically productive water, nor greater intrigue in its mastery Appellations such as Eufaula, Seminole and Ouachita were uttered like evening vespers, “pattern,” “structure” and “holding cover” were part of an elite new mantra, fresh products hit the sporting counters almost weekly, and the excitement was as infectious as measles. Bass fishermen were gathering spiritually, akin to folks at a Wednesday-night tent revival…ready for religion, but waiting for the right sermon.

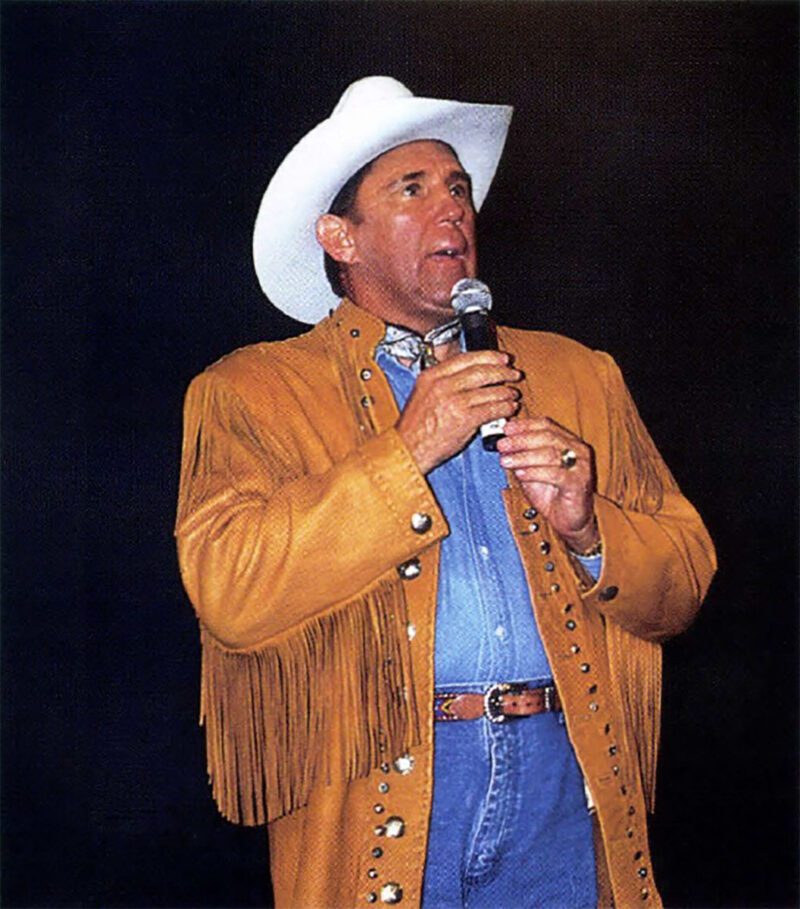

Like an evangelist drawn to Calvary, a resourceful dreamer named Ray Wilson Scott, Jr. took the pulpit and preached the Bass Anglers Sportsman Society (see “The Bass God.” Jan/ Feb ’96) It pressed the right button. The congregation was in the aisles, thumping the plate, shouting HALLELUJAHS! Nevertheless, Scott lived on faith fora time. “I made $26,000 in 1966, the last full year I was in insurance,” he recalls. “The first year of B.A.S.S. I maybe cleared $5,000. I survived, but by nothing more than the grace of God. I had no grand, passionate vision of a great revolution, much less a multi-billion-dollar industry, but I could sense something gathering.”

I remember my personal invitation from Ray Scott for charter membership in B.A.S.S. on March 5, 1969, advising that I had been duly endorsed as an “enthusiastic bass fisherman” and “recommended” by a friend, cleverly intimated. A few days later, my Charter Membership Certificate was in hand. On parchment bearing a gold BAS.S. seal, arriving just as the ink cooled, it “commissioned” me to “promote and elevate our Bass fishing sport to national prominence.”

It was a charge I and thousands of other fishermen across the country took to heart. B.A.S.S. emblems were affixed like diadems, slapped on everything from camper shells to toilet tops.

Today, the organization has a congress of state federations, 2,800 affiliated clubs (there’s even one in Italy), and upwards of 600,000 members.

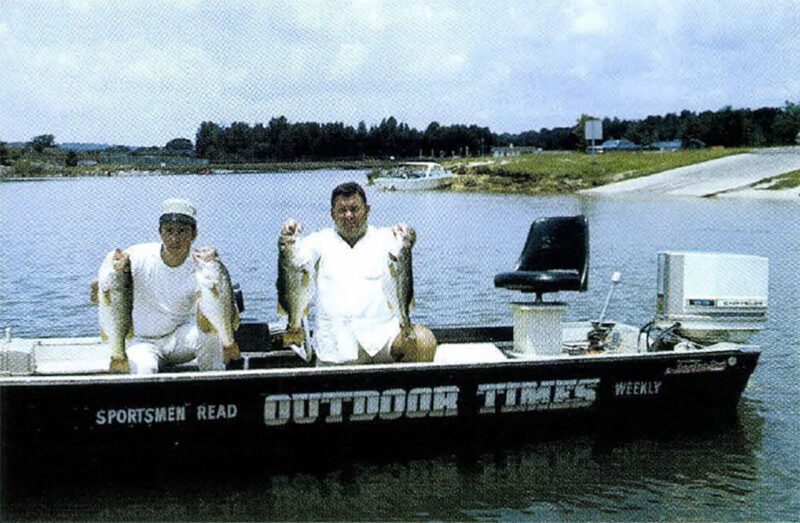

The B.A.S.S. Tournament Trail, the backbone of the enterprise, hit the water slightly before the organization itself with the first All American (what else?) Bass Tournament, orchestrated by Ray Scott on Beaver Lake, Arkansas, June 5-7,1967. One-hundred-six fishermen plunked down $100 apiece to compete for $5,000 in cash and prizes. The winner, Stan Sloan, a Nashville police officer, pocketed $2,000 and an unheralded trip to Acapulco On August 9, 1997, B.A.S.S. Masters Classic XVII, the 277th event in its tournament history, was concluded on Lake Logan Martin, Alabama. Bassing’s “Test of the Best” awarded a cool $101,000 to victorious circuit pro Dion Hibdon, only a fraction of the earnings he may expect over the next five years from sponsor contracts, endorsements, bonuses and seminar engagements. The weigh-in extravaganza and accompanying Classic Outdoor Show drew a live crowd of almost 100,000; an estimated 1.5 million viewers caught the nationwide TV simulcast. A long ways, baby, from a 50s flat-bottom and the yearly bass contest at the hometown hardware store.

The B.A.S.S. Tournament Trail, the backbone of the enterprise, hit the water slightly before the organization itself with the first All American (what else?) Bass Tournament, orchestrated by Ray Scott on Beaver Lake, Arkansas, June 5-7,1967. One-hundred-six fishermen plunked down $100 apiece to compete for $5,000 in cash and prizes. The winner, Stan Sloan, a Nashville police officer, pocketed $2,000 and an unheralded trip to Acapulco On August 9, 1997, B.A.S.S. Masters Classic XVII, the 277th event in its tournament history, was concluded on Lake Logan Martin, Alabama. Bassing’s “Test of the Best” awarded a cool $101,000 to victorious circuit pro Dion Hibdon, only a fraction of the earnings he may expect over the next five years from sponsor contracts, endorsements, bonuses and seminar engagements. The weigh-in extravaganza and accompanying Classic Outdoor Show drew a live crowd of almost 100,000; an estimated 1.5 million viewers caught the nationwide TV simulcast. A long ways, baby, from a 50s flat-bottom and the yearly bass contest at the hometown hardware store.

Love it or loathe it. in its 30-year span the B.A.S.S. Tournament Trail has been the most uncompromising underwriter’s laboratory in history for freshwater gear and equipment. has made professional bassing a lucrative reality, showcased bass fishing to national celebrity, and institutionalized the country’s most inviolable and consequential catch-and-release ethic.

Bassing’s Deadliest Triad: Sonar, Plastic Worms and Structure Theory

Fish-finder logic, plastic worm technique, and supposition of deep-water bass behavior wandered through the early 60s in addled essence, like gifted teenagers seeking life’s purpose. At the close of the decade, however, spurred by the new B.A.S.S. Tournament Trail, each had come to consummation. In the summer of 1969, the three were so perfectly and initially allied within an ideal time and place that the result became one of the most sensational in bass-fishing annals.

On May 24, Georgian Pete Henson won the Rebel Invitational B.A.S.S. Tournament on Ross Barnett That wasn’t the news. The word was how he did it Anchoring on a ditch from deep-water timber to a shallow flat, he never moved his boat more than a few feet the entire three days, and boarded a whopping 124 pounds, 3 ounces. Henson would be accused of “sitting so stubbornly that he was mistaken for a channel marker.” Less than two months later, on a scorching day in mid-July at the Eufaula National, Rip Nunnery stunned the tournament fishing world with the reigning B.A.S.S single-day catch record: 15 fish totaling 98 pounds, an average of more than 6.5 pounds per fish! Fishing in 18-20 feet of water over trees and snags, he boated 30 fish on 31 strikes, culling to the 15-fish limit. His partner added another 86 pounds to the live well! They broke a boat paddle trying to shoulder Nunnery’s gigantic string to the weight-in.

Nunnery finished the three days with almost 118 pounds of bass and, unbelievably, managed only third — behind Bill Dance and Blake Honeycutt Honeycutt, a veteran from Hickory, North Carolina, also fishing submerged timber on underwater drops with a Texas-rigged Jelly Worm, mostly one tree, stumbled to the scales with an incredible 138 pounds, 6 ounces of pot-bellied largemouths! Honeycutt’s catch remains the all-time B.A.S.S. Tournament Trail record.

“Structure fishing,” a.k.a. “hole sittin’,” emerged from Eufaula a gold-plated phenomenon — cutting-edge bassing, savoir faire. Practicing an elite knowledge of bass migration onto and about sub-surface topography and cover, you hunted with a depth-finder for a deep-water honey hole holding numbers of bass. Then you hunkered down and used the snagless versatility of a plastic worm rig to reap the benefits. Structure fishing and bass boats become inseparable to the image of modern fishing, and unimaginable stringers of lunkers would be mined from untapped bonanzas nationwide.

Florida Bass in California

In early 1959, a US Navy Transport flying a training mission from Pensacola to San Diego brought 20,000 Florida-strain bass fry (Micropterus salmoides Floridanus)to California. Heavily parasitized and inadequately oxygenated, few of the tiny fish survived. Immediately, a repeat mission was mounted. It stocked an equal number of healthy fry into Upper Otay Lake, a small, bowl-shaped30-acre brood pond and hatchery Florida bass had invaded California, and the aftermath would send the sportfishing world reeling.

From 1960-62, Floridas from Upper Otay were released in a series of small San Diego impoundments Sutherland, Wohlford, Lower Otay, Miramar and EI Capitan Through the balance of the decade, Florida bass continued to be stocked into other Golden State lakes. Rich with forage, especially rainbow trout and golden shiners, the diminutive waters proved perfect incubators for the aggressive Floridas, which dominated and bred freely with its northern cousin and grew twice as fast.

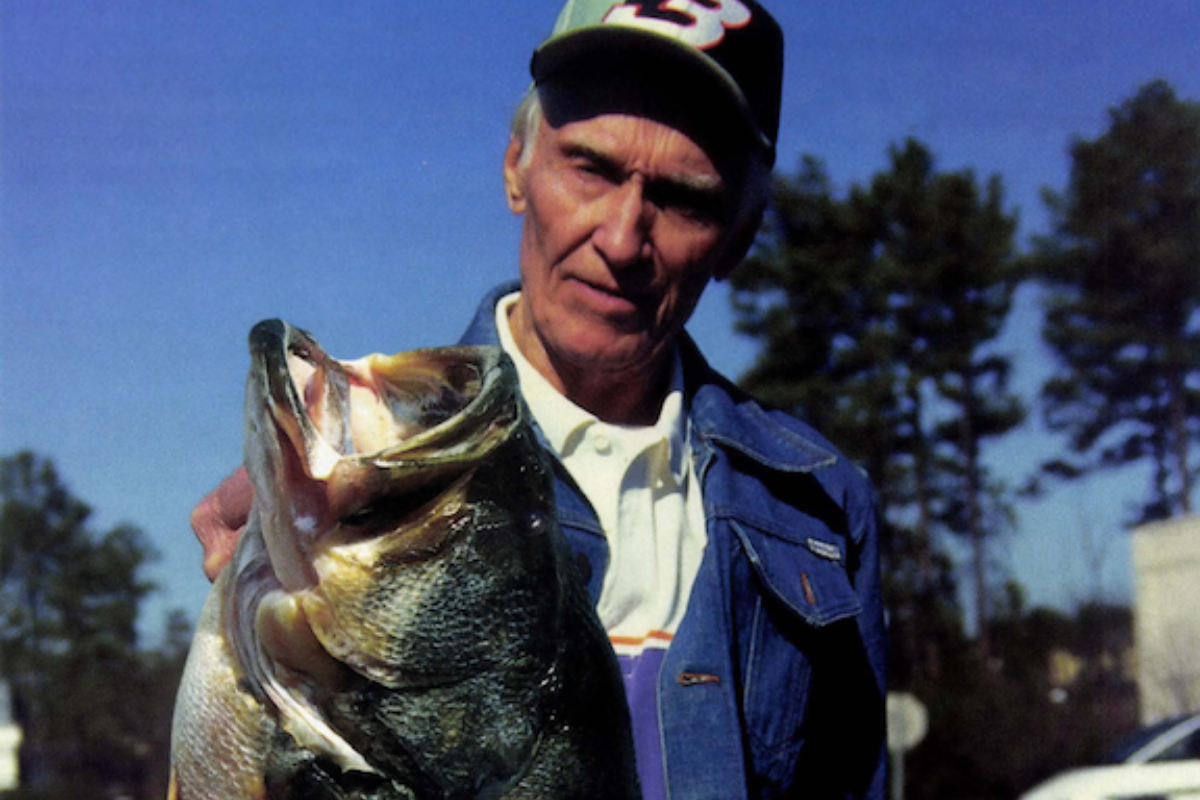

In the mid-60s, catches of six- to nine-pound Floridas became ordinary. In 1968, the 14-pound state record of 20years was demolished – then four times more in the next five years. By 1972, the ante stood at a whopping 17 pounds,14 ounces. On June 23, 1973, Dave Zimmerlee, a Missouri transplant himself, landed the 20-pound, 15-ounce behemoth that absolutely blew the doors off the trolley. His fish was a 12- to 14-year-old believed to have been spawned from original Lake Miramar stock. Almost overnight, hopes for a new world record became a suspense saga.

Intrigue gathered like sweat on a beaded glass! California biologists forecast a new world record within 24months, probably from Miramar. No less than Uncle Homer Circle, Sports Afield’s angling editor emeritus, agreed. “We have seen the next world record bass and we know where it lives” — “the countdown is ticking” — “yes, it could happen at any moment.”

It almost did, though more than a few moments later, with Bob Cruppi’s cliffhanging 22-pound monster of March 12, 1991, from Lake Castaic. Cruppi’s fish was a mere four ounces shy of Valhalla, and the Golden State is reputed to own 22of the best 25 largemouths of all time. California’s best includes two largemouths that topped 21 pounds, though lately, it seems, anything that gets really close to that weight is corroded with controversy.

Still, as perhaps the most portentous legacy of the 60s,transplanted Florid as continue to hold bass fishermen enchanted, if no longer breathless.

Epilogue

The 70s would explode with gear and technology, bring TV coverage, and incite the growing adulation of fans home and abroad. The eighties and nineties would rain glitz and glory. But the magic, the heart and soul of modern bassing, belongs to the 60s.Bassing pioneer and 1969 Eufaula Champion Blake Honeycutt puts it well.

“I was there, saw it all. It [the decade] revolutionized the sport, brought it to national prominence . . . generated a whole new breed of American hero. It was an exciting time to be alive!”

The Swinging 70s

If the 60s launched modern bassing, the 70skicked it full throttle, out of the hole, and onto the pads. The tempo was as catchy as a Bee Gee’s medley, and from Tallahassee to Toledo, the bass movement was in a strut.

The push was for power. Tournament power. By 1970, the B.A.S.S. Tournament Trail was three years old and thriving. Throughout the decade, each successive event would be a flashing strobe, disclosing the latest in tackle and tactic, illuminating another hero, pulsing with the charisma of big-time bassing. Largemouth passion was fanned so hot that it blew in an explosive swirl of sparks across the nation, igniting local contests by the hundreds, and inciting new legions to the ranks. Seasoned pro or star-crossed upstart, everyone scrambled for an edge. A battalion of entrepreneurs rushed to provide it, and gear and gadgetry rained like wind-driven spray.

Early on, with the bass boat still the center of the universe and its fabricators almost as ubiquitous as the craft itself, Ranger outstripped the pack with a revolutionary 18-foot TR-3. It boasted an unprecedented 64-inch beam and a whopping 140-horse rating! Five years of hard-charging, hull-pounding contention had driven home the point if you wanted to run with the big boys on big water, it better be bigger and broader.

Never a sideliner in a power play, Mercury Marine was there to greet it, with a stacked-six transom hanger that powered out at an exact 140. A year later, with at least one eye cocked at the burgeoning world of contest bassing, the company “power-ported” the same engine, harnessing another ten horses “for men who thought running second was running nowhere.” In 1976, its blood really up, Mercury unleashed the awesome 150 V-6 “Black Max.” Housed under a cowling as broad as a northbound gospel singer, sporting the way-cool, chin-in-the-wind icon of Max himself, it was unmistakably BAD! Complimented by a jackplate, trim unit, Hot-Foot and high-rake prop, it made the run to a remote honey hole a mile-a-minute handy.

Even America’s oldest maker of grandfather clocks joined the fray. In 1970, the Herschede Clock Company marketed a remote-controlled electric kicker called the “Motor Guide.” Tourney-tough and brawny, it won the respect of the frontrunners, freeing hands for fishing. On its heels, the 24-voltSuper Motor Guide, “25 percent more powerful” made the bow-mounted, foot-controlled, high-thrust electric a bass-rig necessity.

Heavier rigs blew eight-inch tires like maypops. So along came Everglades and Wonder State with the first of the drive-on, big-wheel trailers. Custom-fitted, with an adjustable undercarriage riding 4-ply, 6.50 by 13s on high-speed bearings, they kept the hook out of your hull and tamed the mileage. At the ramp, six boat-guides helped you load in a crosswind, while dual risers kept the tail-lights high and dry. White sidewalls, chrome wheel covers and pin-striped DuPont DeLux enamel made certain you reached the weigh-in with style.

As early as ’72, you could get all of the above, plus Machine Design, Inc.’s “Pro-Throne” jump-seat, power-pedestals and a lot more, in dealer-rigged packaging. Before you did, you could check out the Ranger Classic rig, specially appointed for the B.A.S.S. Master Classic. Then, as every year since, it showcased the hottest in bass boat goodies, including enough console instrumentation to rival a fighter cockpit.

Invention was hardly a corporate monopoly. A good-ol’ Tennessee boy named Fred Young whittled a way-out fishing plug from a chunk of balsa. It looked like a perch fry stuck to an oversized egg-sac. Young glued it to a small diving lip and passed it to brother Otis, who pronounced it bass-worthy. So Fred carved a few more and put them up in egg cartons for his tourney friends. Hail the “Big-O,” the soon-to-be-famous crank-bait, pregnant-perch original, which sold for a crazed $25 or more a pop before Young was overwhelmed and Cordell took over. Lure-makers exhausted the alphabet with copies: Big-Os, Big-Bs, Fat Alberts, Big-Ns and Big-Hedds, et al., were the rage.

Don Butler and Stan Sloan did something similar with their Okie-Bug, S.O.B. (Small Okie-Bug), and Aggravator safety-pin spinnerbaits Bushwhackers, Bush Hogs, Buzz Spins, Tarantulas and Destroyers become so trendy it took an extra tackle box just to stable them. Buzz-baits, rattle-plugs, finesse baits, Carolina rigs, flippin’, pitchin’, slow rollin’: all children of the 70s.

Oxygen monitors to pH meters, “Speed” rings to Sur Temps, kill switches to 60 mph transducers, Astro-Turf to Zorros, it happened in the swinging 70s.

The 70s put the topspin on high-tech bassing, and booted it right on into the 90s.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 1998 July/August issue of Sporting Classics.

Classic writing remains “classic” only insofar as people want to read it. Angling historians may study the evolution of tackle or tying techniques, or perhaps the methods of fishing used hundreds of years ago, but the wonderful stories about fishing are read and reread only because they give pleasure today; because they give us insights into why we fish and the nature of our passion; and because they are well written. This book offers sixteen of the best classic fishing stories that have stood the inescapable test of time. Buy Now

Classic writing remains “classic” only insofar as people want to read it. Angling historians may study the evolution of tackle or tying techniques, or perhaps the methods of fishing used hundreds of years ago, but the wonderful stories about fishing are read and reread only because they give pleasure today; because they give us insights into why we fish and the nature of our passion; and because they are well written. This book offers sixteen of the best classic fishing stories that have stood the inescapable test of time. Buy Now