“Sharks!” I yelled, hauling away for dear life.

Time is probably more generous and healing to an angler than to any other individual. The wind, the sun, the open, the colors and smells, the loneliness of the sea or the solitude of the stream work some kind of magic. In a few days my disappointment at losing a wonderful fish was only a memory, another incident of angling history.

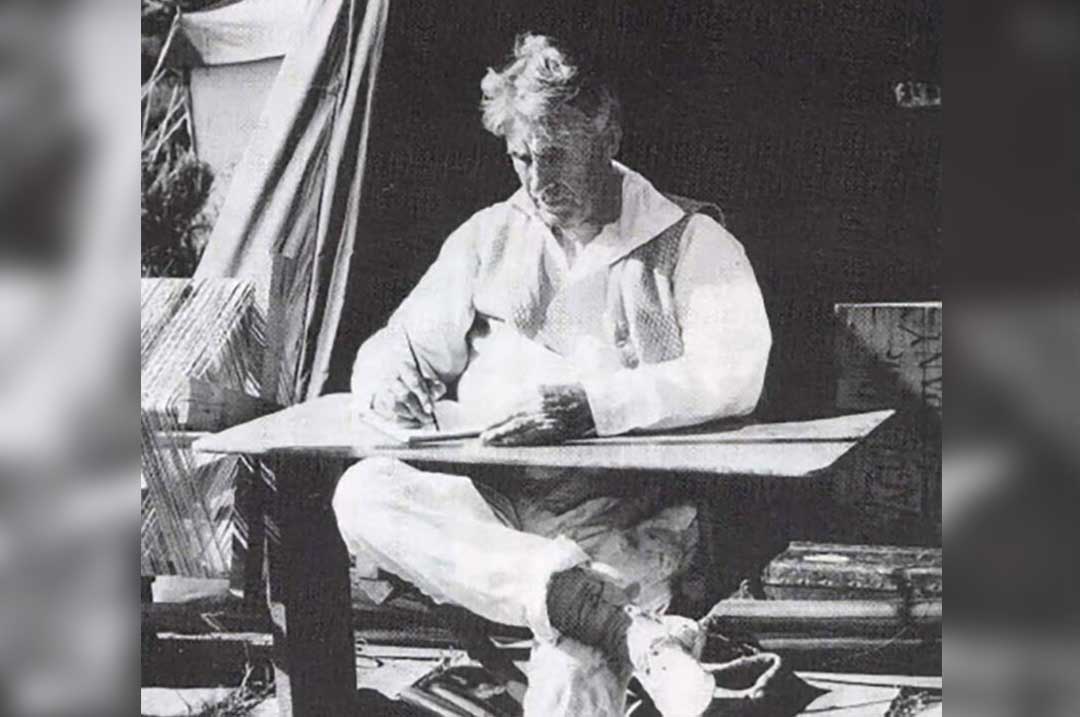

On the 15th of last May, which was the seventh day of clear, hot, sunny weather, I stayed in my camp near Tahiti, in the South Seas, to do some neglected writing, and let Cappy run out alone off the east end, where we had not scouted for several weeks. He returned to report a rather choppy sea, but he had raised two marlin, one of which was a good-sized fish that came for his bait three times, to refuse it, no doubt because it was stale. Tuna, a small species, were numerous, and there was some bonito showing.”

“Same old story,” averred the Captain (Captain Laurie Mitchell). “If I’d had afresh bait I’d have hooked that bird. A lunker, too. All of 500 pounds.” Just what had transpired in my mind I was not conscious of then. It all came to me afterward, and it was that this game was long, and some day one of us might capture a giant Tahitian marlin. We would go on trying.

That night the dry spell broke. The rain roared on the pandanus roof, most welcome and dreamy of sounds. Morning disclosed dark, massed, broken clouds, red-edged and purple-centered, with curtains of rain falling over the mountains. This weather was something like March come back again for a day! Wondrous South Seas!

I took down a couple of new feather gigs — silver-headed with blue eyes — just for good luck. They worked. We caught five fine bonito in the lagoon, right off the point where my cottage stands. Jimmy, one of my natives, held up five fingers: “Five bonito, Good!” he ejaculated, which voiced all our sentiments.

Cappy had gone up the lagoon toward the second pass, and we tried to catch him so as to give him a fresh bait. As usual, however, Cappy’s natives were running the wheels off his launch, and we could not catch him. The second pass looked sort of white and rough tome. Cappy went out, however, through a smooth channel. Presently we saw as well gather and rise, to close the channel and mount to a great, curling, white-crested wave which broke all the way across. Charley, who had the wheel, grinned up at me: ”No good!” We turned inshore and made for the third pass, some miles on, and got through that wide one without risk. Afterward Cappy told me his guide, Areiareia, knew exactly when to run through the second pass.

Cappy had gone up the lagoon toward the second pass, and we tried to catch him so as to give him a fresh bait. As usual, however, Cappy’s natives were running the wheels off his launch, and we could not catch him. The second pass looked sort of white and rough tome. Cappy went out, however, through a smooth channel. Presently we saw as well gather and rise, to close the channel and mount to a great, curling, white-crested wave which broke all the way across. Charley, who had the wheel, grinned up at me: ”No good!” We turned inshore and made for the third pass, some miles on, and got through that wide one without risk. Afterward Cappy told me his guide, Areiareia, knew exactly when to run through the second pass.

We headed out. A few black noddies skimmed the dark sea, and a few scattered bonito broke the surface. As usual — when we had them — we put outa big bonito on my big tackle and an ordinary one on the other. As my medium tackle holds 1,000 yards of39-thread Swastika line it will seem interesting to anglers to speak of it as medium. The big outfit held 1,500 yards of line — 1,000 of 39-thread and 500 yards of 42 for backing; and this story will prove I needed Hardy rod and reel, and the great Swastika line.

Off the east end there was a brightness of white and blue, where the clouds broke, and in the west there were trade wind clouds of gold and pearl, but for the most part a gray canopy overspread mountain and sea. All along the saw-toothed front of this range inshore the peaks were obscured and the canyons filled with down-drooping veils of rain.

What a relief from the late days of sun and wind and wave! This was the kind of sea I loved to fish. The boat ran easily over a dark, low, lumpy swell. The air was cool, and as I did not have on any shirt the fine mist felt pleasant to my skin. John Loef was at the wheel. Bob Camey sat up on top with Jimmy and Charley, learning to talk Tahitian. The teasers and heavy baits made a splashing, swishy sound that could be heard above the boil and gurgle of water from the propellers. We followed some low-skimming boobies for a while, and then headed for Captain M. ‘s boat, several miles farther out. A rain squall was obscuring the white, tumbling reef and slowly moving toward us. Peter Williams sat at my right hand, holding the line which had the larger bonito. He had both feet up on the gunwale. I noticed that the line on this reel was white and dry. I sat in the left chair, precisely as Peter, except that I had on two pairs of gloves with thumbstalls in them. I have cut, burned, and skinned my hands too often on a hard strike to go without gloves. They are a nuisance to wear all day, when the rest of you, almost, is getting pleasantly caressed by sun and wind, but they are absolutely necessary to an angler who knows what he is doing.

Peter (saltwater guide from New Zealand) and I were discussing plans for our great round-the-world trip next year, boats, camp equipment, and what not. And, although our gaze seldom strayed from the baits, the idea of raising a fish was the furthest from our minds. We were just fishing, putting in the few remaining hours of this Tahitian trip, and already given over to the hopes and anticipations of the new one. That is the comfortable way to make a trip endurable — to pass from the hard reality of the present to the ideal romance of the future.

Suddenly I heard a sounding, vicious thump of water. Peter’s feet went up in the air.

“Ge-suss!” be bawled.

His reel screeched. Quick as thought, I leaned over to press my gloved hand on the whizzing spool of line. Just in time to save the reel from overrunning!

Out where Peter’s bait had been showed a whirling, closing hole in the boiling white-green water. I saw a wide purple mass shooting away so close under the surface as to make the water look shallow. Peter fell out of the chair at the same instant I leaped up to straddle his rod. I had the situation in hand. My mind worked swiftly and coolly. It was an incredibly wonderful strike. The other boys piled back to the cockpit to help Peter get my other bait and the teasers in.

Before this was even started the fish ran out 200 yards of line, then, turning to the right, he tore off another hundred. All in a very few seconds! Then a white splash, high as a tree, shot up, out of which leaped the most magnificent of all the leaping fish I ever saw.

Before this was even started the fish ran out 200 yards of line, then, turning to the right, he tore off another hundred. All in a very few seconds! Then a white splash, high as a tree, shot up, out of which leaped the most magnificent of all the leaping fish I ever saw.

“Giant marlin!” screamed Peter. What had happened to me I did not know, but I was cold, keen, hard, tingling, motivated to think and do the right thing. This glorious fish made a leap of 30 feet at least, low and swift, which yet gave me time to gauge his enormous size and species. Here at last on the end of my line was the great Tahitian swordfish! He looked monstrous. He was pale, shiny gray in color, with broad stripes of purple. When he hit the water he sent up a splash like the flying surf on the reef.

By the time he was down I had the drag on and was winding the reel. Out he blazed again, faster, higher, longer, whirling the bonito round his head. “Hook didn’t catch!” yelled Peter, wildly. “It’s on this side, He’ll throw it.”

I had instinctively come up mightily on the rod, winding with all speed, and I had felt the tremendous, solid pull. The big Pflueger hook had caught before that, however, and the bag in the line, coupled with his momentum, had set it.

“No, Peter! He’s fast,” I replied. Still I kept working like a windmill in a cyclone to get up the slack. The monster had circled in these two leaps. Again he burst out, a plunging leap which took him under a wall of rippling white spray. Next instant such a terrific jerk as I had never sustained nearly unseated me. He was away on his run.

“Take the wheel, Peter,” I ordered, and released the drag. “Water! Somebody pour water on this reel! Quick!”

The white line melted, smoked, burned off the reel. I smelled the scorching. It burned through my gloves. John was swift to plunge a bucket overboard and douse reel, rod, and me with water. That, too, saved us.

“After him, Pete!” I called, piercingly. The engines roared, and the launch danced around to leap in the direction of the tight line.

“Full speed!” I added.

“Aye, sir,” yelled Peter, who had been a sailor before he became a whaler and a fisherman.

Then we had our race. It was thrilling in the extreme, and, though brief, it was far too long for me. A thousand yards from us — over half a mile — he came up to pound and beat the water into a maelstrom.

“Slow up!” I sang out. We were bagging the line. Then I turned on the wheel drag and began to pump and reel as never before in all my life. How precious that big spool-that big reel handle! They fairly ate up the line. We got back 500 yards of the 1,000 out before he was off again. This time, quick as I was, it took all my strength to release the drag, for when a weight is pulling hard it releases with extreme difficulty. No more risk like that!

He beat us in another race, shorter, at the end of which, when he showed like a plunging elephant, he had out 750 yards of line.

“Too much-Peter!” I panted. “We must — get him closer! Go to it!”

So we ran down upon him. I worked as before, desperately, holding on my nerve, and, when I got 500 yards back again on the reel, I was completely winded, and the hot sweat poured off my naked arms and breast.

“He’s sounding! Get my shirt — harness!”

Warily I let go with one hand and then with the other, as John and Jimmy helped me on with my shirt, and then with the leather harness. With that hooked on to my reel and the great strain transferred to my shoulders, I felt that I might not be tom asunder.

Warily I let go with one hand and then with the other, as John and Jimmy helped me on with my shirt, and then with the leather harness. With that hooked on to my reel and the great strain transferred to my shoulders, I felt that I might not be tom asunder.

“All set. Let’s go,” I said grimly. But he had gone down, which gave me a chance to get back my breath. Not long, however, did he remain down. I felt and saw the line rising.

“Keep him on the starboard quarter, Peter. Run up on him now. Bob, your chance for pictures!”

I was quick to grasp that the swordfish kept coming to our left, and repeatedly on that run I had Peter swerve in the same direction, so as to keep the line out on the quarter. Once we were almost in danger. But I saw it. I got back all but 100 yards of line. Close enough. He kept edging in ahead of us, and once we had to turn halfway to keep the stem toward him. But he quickly shot ahead again. He was fast, angry, heavy. How his tail pounded the leader. The short, powerful strokes vibrated all over me.

“Port — port, Peter,” I yelled, and even then, so quick was the swordfish, that I missed seeing two leaps directly in front of the boat, as he curved ahead of us. But the uproar from Bob and the others was enough for me.

As the launch sheered around, however, I saw the third of that series of leaps — and if anything could have loosed my chained emotion on the instant, that unbelievably swift and savage plunge would have done so. But I was clamped. No more dreaming! No more bliss! I was there to think and act. And I did not even thrill.

By the same tactics the swordfish sped off a hundred yards of line, and by the same we recovered them and drew. Close to see him leap again, only 200 feet off our starboard, a little ahead, and of all the magnificent fish I have ever seen he excelled. His power to leap was beyond credence. Captain M.’s big fish, that broke off two years before, did not move like this one. True, he was larger. Nevertheless, this swordfish was so huge that when he came out in dazzling, swift flight, my crew went simply mad. This was the first time my natives had been flabbergasted. They were as excited, as carried away, as Bob and John. Peter, however, stuck at the wheel as if he were after a wounded whale which might any instant turn upon him. I did not need to warn Peter not to let that fish hit us. If he had he would have made splinters out of that launch. Many an anxious glance did I cast toward Cappy’s boat, two or three miles distant. Why did he not come? The peril was too great for us to be alone at the mercy of that beautiful brute, if he charged us either by accident or design. But Captain could not locate us, owing to the misty atmosphere, and missed seeing this grand fish in action.

How sensitive I was to the strain on the line! A slight slackening directed all my faculties to ascertain the cause. The light at the moment was bad, and I had to peer closely to see the line. He had not slowed up, but he was curving back and to the left again — the cunning strategist!

“Port, Peter — port!” I commanded.

We sheered, but not enough. With the wheel hard over, one engine full speed ahead, the other in reverse, we wheeled like a top. But not swift enough for that Tahitian swordfish. The line went under the bow.

“Reverse!” I called, sharply.

We pounded on the waves, slowly caught hold, slowed, started back. Then I ordered the clutches thrown out. It was a terrible moment, and took all my will not to yield to sudden blank panic.

When my line ceased to payout, I felt that it had been caught on the keel. And as I was only human, I surrendered for an instant to agony. But no! That line was new, strong. The swordfish was slowing. I could yet avert catastrophe.

“Quick, Pete. Feels as if the line is caught,” I cried, unhooking my harness from the reel.

Peter complied with my order. “Yes, by cripes! It’s caught. Overboard, Jimmy! Jump in! Loose the line!”

The big Tahitian in a flash was out of his shirt and bending to dive.

”No! Hold on, Jimmy!” I yelled. Only a moment before I had seen sharks milling about. “Grab him, John!”

They held Jimmy back, and a second later I plunged my rod over the side into the water, so suddenly that the weight o fit and the reel nearly carried me overboard.

“Hold me — or it’s all — day!” I panted, and I thought that if my swordfish had fouled on keel or propellers I did not care if I did fall in.

“Hold me — or it’s all — day!” I panted, and I thought that if my swordfish had fouled on keel or propellers I did not care if I did fall in.

“Let go my line, Peter,” I said, making ready to extend the rod to the limit of my arms.

“I can feel him moving, sir,” shouted Peter, excitedly. “By jingo! He’s coming! It’s free! It wasn’t caught!”

That was such intense relief I could not recover my balance. They had to haul me back into the boat. I shook allover as one with the palsy, so violently that Peter had to help me get the rod in the rod socket of the chair. An instant later came the strong, electrifying pull on the line, the scream of the reel. Never such sweet music! He was away from the boat — on a tight line! The revulsion of feeling was so great that it propelled me instantaneously back into my former state of hard, cold, calculating, and critical judgment, andiron determination.

“Close shave, sir,” said Peter, cheerily. “It was like when a whale turns on me, after I’ve snuck him. We’re all clear, sir, and after him again.”

The gray pall of rain bore down on us. I was hot and wet with sweat, and asked for a raincoat to keep me from being chilled. Enveloped in this I went on with my absorbing toil. Blisters began to smart on my hands, especially one on the inside of the third finger of my righthand, certainly a queer place to raise one. But it bothered me, hampered me. Bob put on his rubber coat and, protecting his camera more than himself, sat out on the bow waiting.

My swordfish, with short, swift runs, took us five miles farther out, and then, welcome to see, brought us back, all this while without leaping, though he broke water on the surface a number of times. He never sounded after that first dive. The bane of an angler is a sounding fish, and here in Tahitian waters, where there is no bottom, it spells catastrophe. The marlin slowed up and took to milling, a sure sign of a rattled fish. Then he rose again, and it happened to be when the rain had ceased. He made one high, frantic jump about 200 yards ahead of us, and then threshed on the surface, sending the bloody spray high. All onboard were quick to see that sign of weakening, of tragedy — blood.

Peter turned to say, coolly: “He’s our meat, sir.”

I did not allow any such idea to catch in my consciousness. Peter’s words, like those of Bob and John, and the happy jargon of the Tahitians, had no effect upon me whatever.

It rained half an hour longer, during which we repeated several phases of the fight, except slower on the part of the marlin. In all he leaped fifteen times clear of the water. I did not attempt to keep track of his threshings.

After the rain passed I had them remove the rubber coat, which hampered me, and settled to a slower fight. About this time the natives again sighted sharks coming around the boat. I did not like this. Uncanny devils! They were the worst of these marvelous fishing waters. But Peter said: “They don’t know what it’s all about. They’ll go away.”

They did go away long enough to relieve me of dread, then they trooped back, lean, yellow-backed, white-finned wolves.

“We ought to have a rifle,” I said. “Sharks won’t stay to be shot at, whether hit or not.”

It developed that my swordfish had leaped too often and run too swiftly to make an extremely long fight. I had expected a perceptible weakening and recognized it. So did Peter, who smiled gladly. Then I taxed myself to the utmost and spared nothing. In another hour, which seemed only a few minutes, I had him whipped and coming. I could lead him. The slow strokes of his tail took no more line. Then he quit wagging.

“Clear for action, Pete. Give John the wheel. I see the end of the double line. There!”

I heaved and wound. With the end of the double line over my reel I screwed the drag up tight. The finish was insight. Suddenly I felt tugs and jerks at my fish.

“Sharks!” I yelled, hauling away for dear life.

“Sharks!” I yelled, hauling away for dear life.

Everybody leaned over the gunwale. I saw a wide, sheery mass, greenish silver, crossed by purple bars. It moved. It weaved. But I could drag it easily.

“Manu! Manu!” shrilled the natives.

“Heave!” shouted Peter, as he peered down.

“By God! They’re on him!” roared Peter, hauling on the leader. “Get the lance, boat hook, gaffs-anything. Fight them off!”

Suddenly Peter let go the leader and, jerking the big gaff from Jimmy, he lunged out. There was a single enormous roar of water and a sheeted splash. I saw a blue tail so wide I thought I was crazy. It threw a six-foot yellow shark into the air!

“Rope his tail, Charley,” yelled Peter. “Rest of you fight the tigers off.”

I unhooked the harness and stood up to lean over the gunwales. A swordfish rolled on the surface, extending from forward of the cockpit to two yards or more beyond the end. His barred body was as large as that of an ox. And to it sharks were clinging, tearing, out on the small part near the tail. Charley looped the great tail, and that was a signal for the men to get into action.

One big shark had a hold just below the anal fin. How cruel, brutish, ferocious! Peter made a powerful stab at him. The big lance head went clear through his neck. He gulped and sank. Peter stabbed another underneath, and still another. Jimmy was tearing at sharks with the long-handled gaff, and when he hooked one he was nearly hauled overboard. Charley threshed with his rope; John did valiant work with the boat hook, and Bob frightened me by his daring fury, as he leaned far over to hack with the cleaver.

We keep these huge cleavers on board to use in case we are attacked by an octopus, which is not a far-fetched fear at all. It might happen. Bob is lean and long and powerful. Also he was mad. Whack! He slashed a shark that let go and appeared to slip up into the air.

“On the nose, Bob. Split his nose. That’s the weak spot on a shark,” yelled Peter.

Next shot Bob cut deep into the round stub nose of this big, black shark — the only one of that color I saw — and it had the effect of dynamite. More sharks appeared under Bob, and I was scared so stiff I could not move.

“Take that! And that!” sang out Bob, in a kind of fierce ecstasy. “You will try to eat our swordfish — dirty, stinking pups! Aha! On your beak, huh! Zambesi! Wow, Pete, that sure is the place.”

“Look out, Bob! For God’s sake – lookout!” I begged, frantically, after I saw a shark almost reach Bob’s arm.

Peter swore at him. But there was no keeping Bob off those cannibals. Blood and water flew all over us. The smell of sharks in any case was not pleasant, and with them spouting blood, and my giant swordfish rolling in blood, the stench that arose was sickening. They appeared to come from all directions, especially from under the boat. Finally, I had to get into the thick of it, armed only with a gaff handle minus the gaff. I did hit one a stunning welt over the nose, making him let go. If we had all had lances like the one Peter was using so effectively, we would have made short work of them. One jab from Peter either killed or disabled a shark. The crippled ones swam about belly up or lopsided, and stuck up their heads as if to get air. Of all the bloody messes I ever saw, that was the worst.

“Makes me remember-the war!” panted Peter, grimly.

And it was Peter who whipped the flock of ravenous sharks off. Chuck! went the heavy lance, and that was the end of another. My heart apparently had ceased to function. To capture that glorious fish, only to see it devoured before my eyes!

Run ahead, Johnny, out of this bloody slaughter hole, so we can see,” called Peter. John ran forward a few rods into clearwater. A few sharks followed, one of which did so to his death. The others grew wary; they swam around.

Run ahead, Johnny, out of this bloody slaughter hole, so we can see,” called Peter. John ran forward a few rods into clearwater. A few sharks followed, one of which did so to his death. The others grew wary; they swam around.

“We got ’em licked! Say, I had the wind up me,” said Peter. “Who ever saw the like of that? The bloody devils!”

Bob took the lance from Peter, and stuck the most venturesome of the remaining sharks. It appeared then that we had the situation in hand again. My swordfish was still with us, his beautiful body bitten here and there, his tail almost severed, but not irreparably lacerated. All around the boat wounded sharks were lolling with fins out, sticking ugly heads up, to gulp and dive.

There came a let-down then, and we exchanged the natural elation we felt. The next thing was to see what was to be done with the monster, now we had him. I vowed we could do nothing but tow him to camp. But Peter made the attempt to lift him on the boat. All six of us, hauling on the ropes, could not get his back half out of the water. So we tied him fast and started campward.

Halfway in we espied Cappy’s boat. He headed for us, no doubt attracted by all the flags the ‘boys strung up. There was one, a red and blue flag that I had never flown. Jimmy tied this on his bamboo pole and tied that high on the mast. Cappy bore quickly down on us, and ran alongside, he and all of crew vastly excited.

“What is it? Lamming big broadbill?” he yelled back.

My fish did resemble a broadbill in his long, black beak, his widespread flukes, his purple color, shading so dark now that the broad bars showed indistinctly. Besides, he lay belly up.

”No, Cappy. He’s a giant Tahitian striped marlin, one of the kind we’ve tried so hard to catch,” I replied, happily.

“By gad! So he is. What a monster! I’m glad, old man. My word, I’m glad! I didn’t tell you, but I was discouraged. Now we’re sitting on top of the world again.”

“Rather,” replied Peter, for me. “We’ve got him, Captain, and he’s some fish. But the damn sharks nearly beatus. ”

“So I see. They are bad. I saw a number. Well, I had a 400-poundswordie throw my hook at me, and I’ve raised two more, besides a sailfish. Fish out here again. Have you got any fresh bonito?”

We threw our bait into his boat and headed for camp again. Cappy waved, a fine, happy smile on his tanned face, and called: “He’s a wolloper, old man. I’m sure glad. ”

“I owe it to you, Cap,” I called after him.

We ran for the nearest pass, necessarily fairly slowly with all that weight on our stem. The boat listed halfa foot and tried to run in a circle. It was about 1 o’clock, and the sky began to clear. Bob raved about what pictures he would take.

“Oh, boy, what a fish! If only Romer had been with us! I saw him hit the bait, and I nearly fell off the deck. I couldn’t yell. Wasn’t it a wonderful fight? Everything just right. I was scared when he tried to go under the boat. ”

“So was I, Bob,” I replied, remembering that crucial moment. “I wasn’t,” said Peter. “The other day when we had the boat out at Papeete I shaved all the rough places off her keel. So I felt safe. What puts the wind up me is the way these Tahitian swordfish can jump. Fast? My word! This fellow beat any small marlin I ever saw in my life.”

I agreed with Peter, and we discussed this startling and amazing power of the giant marlin. I put forward the conviction that the sole reason for their incredible speed and ferocity was that evolution, the struggle to survive, was magnified in these crystal-clear waters around Tahiti. We talked over every phase of the fight, and that which pleased me most was the old whaler’s tribute:

“You were there, sir. That cool and quick! On the strike that dry line scared me stiff. But afterward I had no doubt of the result.”

We were all wringing wet, and some of us as bloody as wet. I removed my wet clothes and gave myself a brisk rub. I could not stand erect, and my hands hurt — pangs I endured gratefully.

We arrived at the dock about 3o’clock, to find all our camp folk and a hundred natives assembled to greet us. Up and down had sped the news of the flags waving.

I went ashore and waited impatiently to see the marlin hauled out on the sand. It took a dozen men, all wading, to drag him in. And when they at last got him under the tripod, I approached, knowing I was to have a shock and prepared for it.

But at that he surprised me in several ways. His color had grown darker and the bars showed only palely. Still they were there, and helped to identify him as one of the striped species. He was bigger than I had ever hoped for. And his body was long and round. This roundness appeared to be an extraordinary feature for a marlin spearfish. His bill was 3 feetlong, not slender and rapier-like, as in the ordinary marlin, or short and bludgeon-like, as in the black marlin. It was about the same size all the way from tip to where it swelled into his snout, and slightly flattened on top — a superb and remarkable weapon. The fact that the great striped spearfish Captain Mitchell lost in 1928 had a long, curved bill, like a rhinoceros, did not deter me from pronouncing this of the same species. Right there I named this species, “Great Tahitian Striped Marlin. ” Singularly, he had a small head, only a foot or more from where his beak broadened to his eye, which, however, was as large as that of a broadbill swordfish. There were two gill openings on each side, a feature I never observed before in any swordfish, the one toward the mouth being considerably smaller than the regular gill opening. From there his head sheered up to his humped back, out of which stood an enormous dorsal fin. He had a straight-under maxillary. The pectoral fins were large, wide, like wings, and dark in color. The fin-like appendages under the back of his lower jaw were only about 6 inches long and quite slender. In other spearfish these are long, and in sailfish sometimes exceed 2 feet and more. His body, for 8 feet, was as symmetrical and round as that of a good, big stallion. According to my deduction, it was a male fish. He carried this roundness back to his anal fin, and there further accuracy was impossible because the sharks had tom out enough meat to fill a bushel basket. His tail was the most splendid of all the fish tails I ever observed. It was a perfect bent bow, slender, curved, dark purple in color, finely ribbed, and expressive of the tremendous speed and strength the fish had exhibited.

This tail had a spread of five feet two inches. His length was 14 feet 2 inches. His girth was six feet nine inches. And his weight, as he was, 1,040 pounds.

Every drop of blood had been drained from his body, and this with at least 200pounds of flesh ‘the sharks took would have fetched his true and natural weight to 1,250 pounds. But I thought it best to have the record stand at the actual weight, without allowance for what he had lost. Nevertheless, despite my satisfaction and elation, as I looked up at this appalling shape, I could not help but remember the giant marlin Captain had lost in 1928, which we estimated at 22or 23 feet, or the 20-foot one I had raised at Taudra, or the 28-foot one the natives had seen repeatedly alongside their canoes. And I thought of the prodigious leaps and astounding fleetness of this one I had caught. “My heaven!” I breathed. “What would a bigger one do?”

Every drop of blood had been drained from his body, and this with at least 200pounds of flesh ‘the sharks took would have fetched his true and natural weight to 1,250 pounds. But I thought it best to have the record stand at the actual weight, without allowance for what he had lost. Nevertheless, despite my satisfaction and elation, as I looked up at this appalling shape, I could not help but remember the giant marlin Captain had lost in 1928, which we estimated at 22or 23 feet, or the 20-foot one I had raised at Taudra, or the 28-foot one the natives had seen repeatedly alongside their canoes. And I thought of the prodigious leaps and astounding fleetness of this one I had caught. “My heaven!” I breathed. “What would a bigger one do?”

Editor’s Note: this article originally appeared in the 1984 July/August issue of Sporting Classics.

This book is a selection of some of Grey’s best work, and the stories and excerpts reveal a man who understood that angling is more than an activity–it is a way of seeing, a way of being more fully a part of the natural world. No writer exceeds Zane Grey’s ability to integrate the fishing experience with a world he saw so vividly. Buy Now

This book is a selection of some of Grey’s best work, and the stories and excerpts reveal a man who understood that angling is more than an activity–it is a way of seeing, a way of being more fully a part of the natural world. No writer exceeds Zane Grey’s ability to integrate the fishing experience with a world he saw so vividly. Buy Now