The clean lines and simplicity of all functions in George Hoenig’s Rotary Round Action gun camouflage the creativity and elaborate engineering involved in its creation.

Many premier side-by-side shotguns are sold as round actions, but rounded is the more accurate description. The sharp edges of the flat-sided action bar are sculpted with a gentle radius that blends smoothly into the similarly rounded grip and forend. The upshot is a graceful-looking gun that rides more comfortably in the hand when carried at its balance point. But it isn’t truly a round action.

George Hoenig’s Rotary Round Action is.

Hoenig is as original as his guns. The Idaho gunsmith is the kind of innovative iconoclast who comes along all too rarely. At age 16, as a new immigrant fleeing communism in war-torn eastern Europe, Hoenig entered a California high school shop class and talked his teacher into letting him manufacture a pistol. (This happened in 1952 and is unlikely to ever happen again.) The completed handgun won the teen a national industrial arts competition sponsored by Ford. The next year the precocious kid built a revolver that earned an honorable mention in the same competition.

I’ll bet if the contest were held today, George Hoenig’s rotary action gun would win. I keep calling this a gun instead of rifle because it’s both. And more. Hoenig can build it as an over-and-under rifle, as a shotgun or as a combination. The rifle can house any rimmed centerfire up to 450 Nitro Express or any rimfire.

“I built one in 17 HMR for a squirrel hunter down south,” Hoenig explained. “It shot very well and almost dead flat to 100 yards.”

When he’s feeling especially feisty, Hoenig will turn out his rotary action as a vierling.

Given the perfectly cylindrical, unencumbered receiver on this unique gun, “turned out” is exactly the right phrase describing how it is made. It’s turned elegantly on a lathe with no protruding handles, knobs, levers or switches. It’s the gun world’s ultimate example of form following function. But “turned” also describes its function.

To open the action and expose the chambers for loading, twist the barrels a quarter-turn right. This disengages the two massive locking lugs. Push forward about an inch to expose the hinge plate. The barrels now hinge down at about a 45-degree angle. Drop in two cartridges, raise the barrel, push together and turn to the left. Done.

Hoenig was inspired to design his Rotary Round Action by several life experiences. A big one was his years working at Pachmayr, where among other duties, he had to repair all Sears guns under warranty.

When the action is opened on Hoenig’s rifle, a simple cam on the breech face cocks both strikers.

“I learned what not to build,” he chuckled before enumerating. “No cheap trigger-blocking safeties. No single, selective triggers. And no ejectors. Those were always breaking. Why add all these complicated parts if they aren’t necessary?”

As for the rotating locking lugs, credit cannons. The massive locking lugs of certain heavy artillery turn into recesses at the back of the barrel. These are mechanically simple, rugged, nearly foolproof and can contain massive pressures.

But why apply this to a light, sporting gun?

Simplicity and durability. Traditional break- action doubles pivot around a hinge pin below the axis of the bores. Upon firing, expanding gases create the well-known Newtonian reaction to the action. The barrels leap forward, away from the face of the breech, but their linear motion is interrupted by the under-lug, which pivots around the hinge pin. Breech and barrels spring apart ever so slightly. This isn’t a huge problem with the low pressures generated by shotgun shells. But the 45,000 to 65,000 psi generated by centerfire rifle cartridges . . . ?

Houston, we have a problem.

Actually, two problems because bullets add significant lateral torque when they engage rifling. The rifle is literally trying to rip itself apart. None of this happens in the Rotary Round Action because the locking lugs are directly in line with the chambers, rigidly and evenly connecting breech and barrels. No hinging. And torque only reinforces the lock. No lever or locking device of any kind is needed to keep the action closed. A simple cam on the breech face cocks both strikers when the action is opened. The force required to accomplish this is so minimal that it’s hard to feel, unlike the cocking pressure one feels when opening a traditional break-action.

“I was able to do away with all those forend mechanics, completely eliminate the forend iron, since it isn’t needed for cocking anything,” Hoenig explained as he showed me the gun. “You can remove the barrels from the breech by pulling the extractor slightly back like this. Then simply pull apart.”

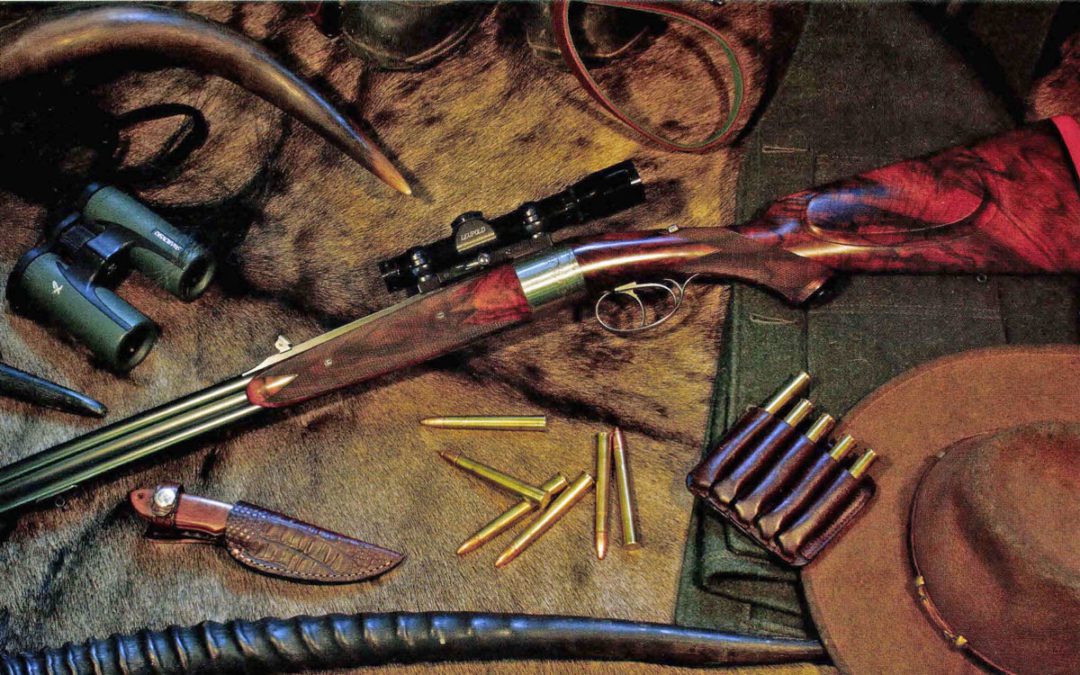

With his innovative Rotary Round Action Rifle, Idaho craftsman George Hoenig set out to design and build a firearm free of “those complicated parts that aren’t really necessary.”

In the next instant he held aloft both barrels with forend wood still attached in his left hand, the receiver and butt in his right. Just as quickly he slipped the two halves back together and locked them closed with a twist of the wrist.

Internally, the action is equally simple and nearly foolproof. The tiny firing pins are driven by strikers powered by coil springs, and all pieces are in a straight line behind the bores. You can dry-fire the gun as often as you want with no ill effects.

The safety directly engages the strikers, holding them back regardless of what the triggers do. Sear and striker engagement provide so much mechanical advantage that the double triggers can be set to break crisply with minimal pull weight. I can vouch for that. The triggers on the rifle I fired in 9.3x74R were just about perfect.

Unloading the gun after filing is dead simple. Merely rotate the barrels again, pull the receiver back one inch to expose the hinge pin and tip the gun upside down while hinging it open. Massive extractors engage half of each cartridge’s rim to push them far out of the chambers, at which point gravity pulls them away. Turn the gun upright, drop in two fresh rounds, push the receiver and barrel together, turn it a quarter-turn left, and you’re ready to shoot again.

The whole operation, like the rifle itself, is a beautiful thing.

Much of that beauty accrues from the marbled walnut chosen for the stock, precise hand-checkering and perfect wood-to-metal fit. The English scroll engraving on the barrel breech, action tang, trigger bow, hinged grip cap and barrel quarter-rib is done by Hoenig’s long-time associate, Owen Bartlett.

George Hoenig (left) and Owen Bartlett build five bespoke guns a year.

Additional touches on the rifle I examined included a flip-over front-sight hood (spare under the grip cap,) barrel-mounted sling stud, shadow-line cheekpiece, and integral quick-release scope mount that facilitates removal and replacement in a second without loss of zero.

The clean lines and simplicity of all functions in the Rotary Round Action camouflage the complicated creativity and elaborate engineering involved in its creation, final testament and compliment to its inventor. Your odds for finding a Hoenig Rotary Round Action gun of any type on a store shelf are slim to none. These are bespoke guns and just five are made each year by the two craftsmen.

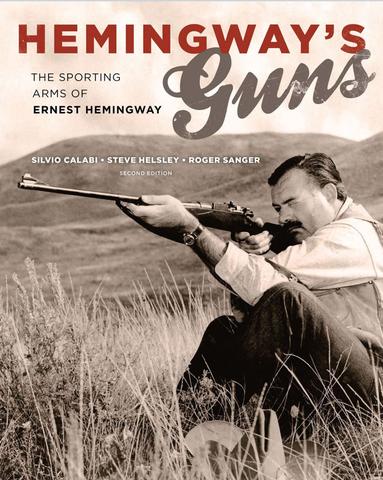

Ernest Hemingway’s friend A.E. Hotchner once described a “yellowed four-by-five picture of Ernest,” shown him by Hemingway, “aged five or six, holding a small rifle. Written on the back in his mother’s hand was the notation, ‘Ernest was taught to shoot by Pa when 2½ and when 4 could handle a pistol.’”

Ernest Hemingway’s friend A.E. Hotchner once described a “yellowed four-by-five picture of Ernest,” shown him by Hemingway, “aged five or six, holding a small rifle. Written on the back in his mother’s hand was the notation, ‘Ernest was taught to shoot by Pa when 2½ and when 4 could handle a pistol.’”Firearms and shooting infused Hemingway’s existence and thus his writing. He was a member of his high-school gun club and went to war when he was eighteen. He hunted elk, deer, and bear in the American west and went on two extended African safaris, which figured hugely in his writing and changed his life. To the day of his death, Hemingway remained an avid hunter, first-class wingshot, and capable rifleman.

Following years of research from Sun Valley to Key West and from Nairobi, Kenya to Hemingway’s home in Cuba, this volume significantly expands what we know about Hemingway’s shotguns, rifles, and pistols—the tools of the trade that proved themselves in his hunting, target shooting, and in his writing. Weapons are some of our most culturally and emotionally potent artifacts. The choice of gun can be as personal as the car one drives or the person one marries; another expression of status, education, experience, skill, and personal style. Including short excerpts from Hemingway’s works, these stories of his guns and rifles tell us much about him as a lifelong expert hunter and shooter and as a man. Buy Now