Ben shouted the Indian’s name until his throat became raw. Much later, on the far side of the camp in rock shadows, he found a note held down and partially hidden by rock.

Ben Choat, the lean, dark-skinned river guide, met the old Indian at the railing entrance of the Colorado River, just below Glen Canyon Dam in late August of 1978. He eyed the beautiful granddaughter as she kissed and hugged her grandfather, Gray Feather, who stood stoic waiting for the guide to finish packing the raft.

Ben Choat, the lean, dark-skinned river guide, met the old Indian at the railing entrance of the Colorado River, just below Glen Canyon Dam in late August of 1978. He eyed the beautiful granddaughter as she kissed and hugged her grandfather, Gray Feather, who stood stoic waiting for the guide to finish packing the raft.

Blinking her eyelashes, Mary gave Ben a look that sent chills through him. As he walked over, she said, “Please take care of him.”

Ben grunted. “I’ve never lost a paying passenger yet.” She smiled, showing white, even teeth, touched Ben’s arm, climbed into a Land Rover, drove up the Winding dirt road away from the river and was soon out of sight.

“We won’t be leaving until noon,” Ben said, eyeing the old man. “There’s fly-fishing equipment on the boat for each of us. After 15 to 20 miles, the river turns a milky brown with no trout. What we eat tonight depends on what we catch.

“We’ll float about 15 miles downriver today and fish again in the morning for our breakfast, and then we’ll eat what I’ve brought, which isn’t much, but it’ll keep us alive. We can fish for trout again near Lake Mead at the other end.”

Gray Feather seemed to look through Ben with no outward show of emotion one way or the other. He lifted a rod, eyed its length for straightness, tested it gently for flexibility, took a box of flies and walked east toward the dam.

Ben grabbed the other rod and flies, and turned downriver, anger riding him for agreeing to take the old fool at all. He’d noted how quickly the old man chose the best rod — his rod. We probably won’t speak to each other the whole way, he thought.

After three hours of tying different flies and casting relentlessly, Ben drew a blank and headed back to the boat.

Gray Feather was resting in the shade of a stand of Cottonwoods set back from water. In the river, tied by twine to a rope attached to the side of the raft, were seven cleaned rainbow trout, none less than 16 inches long.

The Indian eyed Ben and smiled. “Good rod, good fly fisherman. Four are mine. You have three since you don’t seem able to catch trout for yourself. Can you cook them, or do I do that too?”

That night they ate in silence. Ben fumed and avoided looking at the Indian, and Gray Feather seemed completely happy with studying the river, sky, birds, trees and cliffs, a look of contentment pasted across his rugged face.

Ben intended to rise before dawn and make up for being skunked the night before, but when he did wake up, which was early, the old man was landing another trout, attaching it to the same twine where four others thrashed in the shallows.

Ben intended to rise before dawn and make up for being skunked the night before, but when he did wake up, which was early, the old man was landing another trout, attaching it to the same twine where four others thrashed in the shallows.

“Damn,” Ben said aloud as he rolled his gear and grabbed the other rod.

Breakfast was a silent venture, the Indian once again providing meat for the table.

“If you need lessons on fly fishing, boy, we’ll deduct them from the outrageous cost of the trip,” Gray Feather smiled.

Ben looked hard at the old Indian, and then broke out in a laugh. “You’ll do, old man, you’ll do.”

Ben had risen early to climb the vermillion cliff above the Colorado river just below Havasu Rapid. From Lee’s Ferry, his entry point into the river at the foot of Glen Canyon Dam, he was about 150 miles downstream. Ben was at a place where the clear, blue-green water of Havasu Creek flowed into the Colorado — chocolate brown, muddy water now from recent August rains far away and high up in the Arizona desert.

Ben climbed until he could no longer hear the music of rushing water. He watched rocks take form with colors of white, gray, pink and purple as morning sun descended into the canyon on the north side, touching and bathing them with warmth — almost a spiritual experience for him. “Damn,” Ben Choat said softly as he gazed at the colorful formation.

When the light had merged with dancing water, he returned to camp, made cowboy coffee and started cooking another breakfast for Gray Feather.

As he Sipped the strong brew, he thought back to his first meeting with Gray Feather’s granddaughter at his river Outfitter shop in Fredonia, Arizona. The young, black-haired beauty had been both timid and persistent as she persuaded Ben to take her 93-year-old grandfather through the canyon in his two-man raft.

Once they’d left Lee’s Ferry, it had taken them an afternoon and evening to bump into — walk around, make fleeting eye contact and finally bridge the 68-year age difference between their trout-fishing experiences.

When done, it was a forever bonding between an American Indian and a white man.

For six days they had reveled in a celebration of light, speed and color while floating the pristine wilderness river. Bighorn sheep, hawks and deer watched their passage. On day three, Gray Feather, who had far-seeing eyes, spotted a mountain lion sunning on a shelf of rock above the river and pointed it out to Ben.

For six days they had reveled in a celebration of light, speed and color while floating the pristine wilderness river. Bighorn sheep, hawks and deer watched their passage. On day three, Gray Feather, who had far-seeing eyes, spotted a mountain lion sunning on a shelf of rock above the river and pointed it out to Ben.

Gray Feather could read the river almost as well as Ben, and he often shouted as they dropped 10 to 12 feet through big rapids like Sockdolager and Horn Creek, both rated near 10 in afternoon high-water. Both men were soaked to the skin after each rapid, though they dried out quickly in the canyon heat.

At night, the canyon’s ancient rocks cradled them until there was peace in the rhythm of their beating hearts, and for a time, everything was as it should be.

One day Gray Feather asked Ben to tie the raft to some driftwood so he could inspect salt that was imbedded in rock along the south side of the river. He pointed to a hunt trail leading away from the place toward cliffs and crooked canyons.

“The ancient ones came here to gather salt, Tall Brother. It was a pilgrimage for them . . . a long trek through harsh land from their homes.” Then he walked the trail silently until he came to the cliff, his head up, his stride that of a younger warrior, perhaps feeling the spirits of those who passed before.

A footstep behind Ben started him out of his reverie. He turned to watch his new friend walk over to stand on the far side of the fire facing the cliffs. A soft, gentle wind tugged at long strands of white hair that fell below bony shoulders of the Apache Indian and Tribal Elder. Gray Feather’s face was a roadmap of wrinkled skin, leather hard and mahogany brown. His flat nose was spread between high cheekbones, and protruding below bushy eyebrows were wide, deep-set black eyes. His mouth was also wide, with full lips that were cracked from the canyon’s afternoon heat.

A smile played at the corners of Gray Feather’s mouth a she turned to look at Ben. “What are in your thoughts this morning, Tall Brother?”

“I was thinking about my dad. The last time I was home, we fought until I left. I hurt him because I refused to talk about Vietnam. I couldn’t.”

“Do you remember our first night in the canyon?”

“Sure I do. Why?”

“The sounds of the river could not cover your cries as you slept. Each night I heard those sounds until you opened your heart and spoke to me of that place. Now I hear only the sounds of wind and water. A father and son should have no secrets between them, Tall Brother.”

Ben looked into the coal-black eyes of the Apache across from him, and wondered what Gray Feather had been like when he was young. What had he seen and done? How far had he traveled in his lifetime? Where?

“Now, do you intend to sit by the fire all morning like an old, plains Indian squaw sulking, or can you finish cooking my breakfast,” Gray Feather asked, as he poured himself a cup of coffee.

“Finish fixing your own breakfast, Indian. It’s about all you do besides complain all day. I’m going up river; grit my teeth, get wet in 50-degree water and take a bath.”

When Ben returned to camp, Gray Feather was gone. At first, Ben thought the old man had wandered off to look at rocks. Maybe he’d spotted a deer or mountain lion and was following it, but as time passed Ben thought the old man was playing another trick on him, so he doused the fire and then went over to get Gray Feather’s gear.

Except for his sleeping bag, it was gone. A sense of urgency and fear swept over Ben. He started running along the river wondering if the old man had stumbled over a rock and fallen in. Ben shouted the Indian’s name until his throat became raw. Much later, on the far side of the camp in rock shadows, he found a note held down and partially hidden by rock.

Except for his sleeping bag, it was gone. A sense of urgency and fear swept over Ben. He started running along the river wondering if the old man had stumbled over a rock and fallen in. Ben shouted the Indian’s name until his throat became raw. Much later, on the far side of the camp in rock shadows, he found a note held down and partially hidden by rock.

Ben:

If you’re reading this, grandfather has chosen to end his life in the canyon in the Indian way. Several months ago he was diagnosed with liver cancer, and given just a few months to live. He did not want to die in a hospital; he wanted to control the end. Gray Feather said he saw you in a dream. He said you were a warrior in a far land, a Tall Brother with a good heart toward our people. I hope you can forgive me and be with him at the end.

Mary

Ben found it hard to breathe normally. His heart raced, and his hands shook as he read the note over and over. The ever-present murmur of the river, a sound that had been so soothing, was now harsh as it beat against his eardrums. The heat in the canyon swirled around him as a sense of rage swept over him. Fear tore at his guts. The young guide’s mind raced as he thought of all he and Gray Feather had shared. Ben desperately wanted that to continue and soon there emerged an intense determination to find his old friend and take him out of the canyon.

But Ben was no match for his red brother’s skills when it came to tracking. Gray Feather had left prints in sand leading away From the river toward the cliffs, and Ben found pieces of his shirt tied to mesquite brush or held down by rock, and then he left nothing.

“Damn you, old man! This isn’t a game,” Ben shouted as he looked around. “If you wanted me to find you, why did you stop leaving clues?”

Moccasin prints had stopped at the base of a cliff on the south side of the river gorge leading into Havasu canyon. In frustration, Ben began to climb where others before had explored the canyon above the turquoise-colored rock at the bottom of Havasu Creek.

About 200 feet above the creek in the canyon, Ben found the Apache Indian lying with his back against cliff rock, his face pale, sweat beading his brow. Ben heard a soft, “Thank you, Brother Snake,” escape the old man’s lips just as he spotted a big desert rattler slither away into the crevice of a rock outcrop, the ominous sound of its rattles warning him not to follow.

Eyeing the old man, Ben spotted drops of blood mixed with venom seeping from two puncture wounds on his neck, the fang marks a good inch apart, and knew it was a death strike.

The Indian was dressed in a soft-tanned doe skin shirt and leggings. Tanned elk moccasins covered his feet, and a small leather pouch was tied around his neck. One spotted eagle feather was stuck through a beaded leather headband at the back of his head. Ben lifted the Indian and tried to get him to drink water, but Gray Feather’s already swollen lips remained closed. His dark eyes locked on Ben’s as he whispered. “The spirit is here. Can you feel it, Tall Brother?”

“Damn you, I can’t feel anything but fear and anger. We had something, you and me, then you go running off and get mixed up with that rattler, and now I can’t help you. It’s too late. I’ve seen men die, old man. Why did you pick me? Why did you want me here?”

“I chose you . . . saw you in a dream, and we have become brothers. A brother should not die alone, I knew you would come.”

Tears filled Ben’s eyes as he gripped the cold hand of his friend. “Why did you go off like that? I could have helped you. You could have stayed with me and not in a hospital until the end. Why did you let that snake strike you?”

“Tall Brother, how I die is as important to me as how I live. My spirit longs to follow the wind. It is my time, and Brother Snake was the instrument.”

Ben shivered as he leaned back against cliff rock, cradling in his arms the frail body of his friend. Soon, the swelling would close Gray Feather’s ‘windpipe, and death would come slowly and hard. How could a man summon the courage to let a snake strike him like that?

Ben shivered as he leaned back against cliff rock, cradling in his arms the frail body of his friend. Soon, the swelling would close Gray Feather’s ‘windpipe, and death would come slowly and hard. How could a man summon the courage to let a snake strike him like that?

“It is good what you and I shared. Remember it, Tall Brother,” Gray Feather whispered.

Ben wanted to say a hundred things, but knew there was no time to say any of it. I’ll remember, old man. I’ll remember you the rest of my life.”

The Indian’s voice, when it came, was so soft Ben had to lean down to hear his words. “It grows dark. Can you see the eagle floating up there by the canyon rim? My spirit goes to meet it.”

Ben squinted into the late-afternoon sun, unable to see anything. And at that moment, he sensed the Indian’s passing. Ben gently reached down a trembling hand and closed the eyes of his friend for the last time. Softly, in a choked voice, he said, “Fly high, old man. Fly high.”

The rocks, sand, plants and living things of the side canyon caught the strange sounds carried by the wind from high up on the cliff, but were not afraid. It was a softly whispered prayer drawn from the heart of a washboard, gut-thin white man, spoken straight and honest and simple as he stood with his head up, knees unbent, facing his God in the Apache custom of his red brother.

Centuries past, similar sounds echoed through the cliffs by the people who came before. The rocks remembered, and it was good.

Gray Feather had come full circle. A quarter moon of time marked Ben’s progress in the cycle of life, and except for his time in Vietnam, he felt nearly all of it had been lived in the last six days.

In death, the Apache had closed the book on a life so different, and yet so special. Through stories told in the canyon each night, Ben was able to glimpse a part of that life, the history of a man who knew no boundaries, spiritual or physical.

As Ben looked across the rugged canyon in the dim light of early evening, tears came, unashamed and unstoppable. God, how he would miss the old man! Darkness crept down the cliffs, and sometime later, fat stars bloomed thick and white in the night sky. Time dried Ben’s tears, and after a while, the rhythm of the rocks and river crept back into his soul to soothe and hold him until there was peace.

In the early light and quiet of the morning, Ben Choat gathered rocks and placed them around and then over the blanket-wrapped body of the Apache Indian whose earth name was Gray Feather. A Single spotted eagle feather was all that was left to mark the grave.

Only God and Ben Choat know the place, and will remember.

Five days later, Ben made two telephone calls from a pay phone at the outskirts of Las Vegas, Nevada. “Mary, it’s Ben. Gray Feather . . .” He gripped the telephone so hard his knuckles turned white as he fought to control his emotions. His breathing was ragged and his voice trembled as he softly said, “Your grandfather died in the canyon. I buried him there.”

For a long time he stood listening to her cry, feeling her grief as tears rolled down his cheeks. When he was able to talk again, he said, “I’ll be at your home in about an hour to tell you the story.” Ben waited for an answer and then hung up.

For a long time he stood listening to her cry, feeling her grief as tears rolled down his cheeks. When he was able to talk again, he said, “I’ll be at your home in about an hour to tell you the story.” Ben waited for an answer and then hung up.

The quarters made a musical, clinking sound as they tumbled out of sight into the telephone box on his second call. On the seventh ring, a voice said, “Hello?”

Ben’s breath trembled . . . “H-Hey, Dad.”

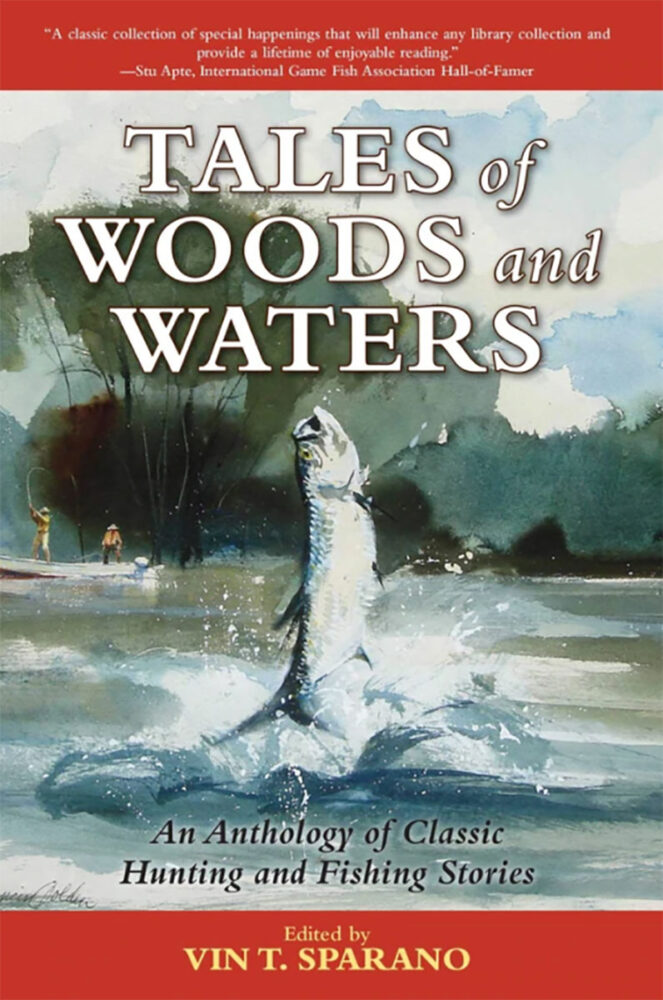

In Tales of Woods and Waters, well-known outdoor editor Vin T. Sparano has collected thirty-seven of the greatest, most enjoyable, and most well-written outdoors stories to have been published. Experience the tension of hunting in the jungles of Tanzania in Jim Carmichael’s “Kill the Leopard,” the joys of your first .22 in Garth Sanders’s “My First Rifle,” the nuances of river fishing in Frank Conaway’s “Big Water, Little Men,” and the enduring challenge of turkey hunting in Charles Elliott’s “The Old Man and the Tom.” Spanning the world and its varied forms of wildlife, these stories demonstrate that no matter where one hunts, shoots, or fishes, the outdoors will always be an important place to form memories that last a lifetime. Buy Now

In Tales of Woods and Waters, well-known outdoor editor Vin T. Sparano has collected thirty-seven of the greatest, most enjoyable, and most well-written outdoors stories to have been published. Experience the tension of hunting in the jungles of Tanzania in Jim Carmichael’s “Kill the Leopard,” the joys of your first .22 in Garth Sanders’s “My First Rifle,” the nuances of river fishing in Frank Conaway’s “Big Water, Little Men,” and the enduring challenge of turkey hunting in Charles Elliott’s “The Old Man and the Tom.” Spanning the world and its varied forms of wildlife, these stories demonstrate that no matter where one hunts, shoots, or fishes, the outdoors will always be an important place to form memories that last a lifetime. Buy Now