The date was Tuesday, January 22,1929. There was nothing to hint that the day would be any different from the many others Sweet had spent fishing through the ice for lake trout, there on the submerged reefs off Crane Island.

Tramping across the rock-strewn, snowy beach of Crane Island with two companions that bitter-cold winter morning, on his way to the rough shore ice and the lake-trout grounds beyond, Lewis Sweet had no warning of what grim fate the next seven days had in store for him, no intimation that before the week was up his name would be on the lips of people and the front pages of newspapers across the whole country. Nor did he guess that he was walking that Lake Michigan beach for the last time on two good feet.

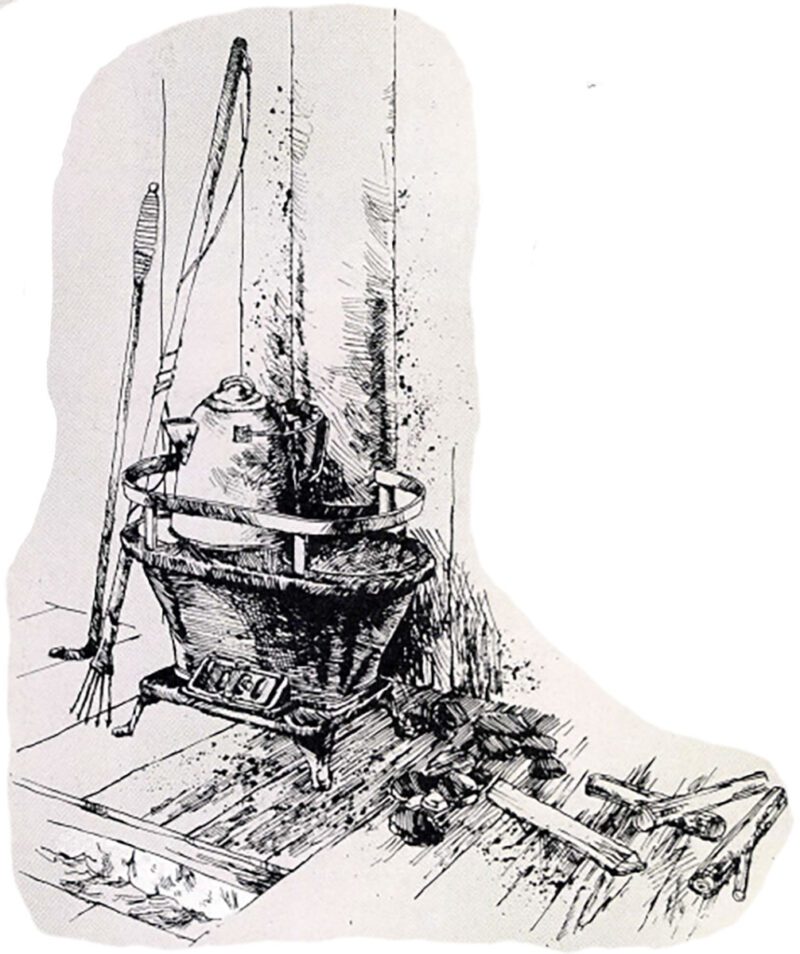

He’d walk out to his lightproof shanty, kindle a fire of dry cedar in the tiny stove, sit and dangle a wooden decoy in the clear green water beneath the ice, hoping to lure a prowling trout within reach of his heavy seven-tined spear. If he was lucky he’d take four or five good fish by midafternoon. Then he’d go back to shore and drive the 30 miles to his home in the village of Alanson, Mich., in time for supper.

It would be just another day of winter fishing, pleasant but uneventful.

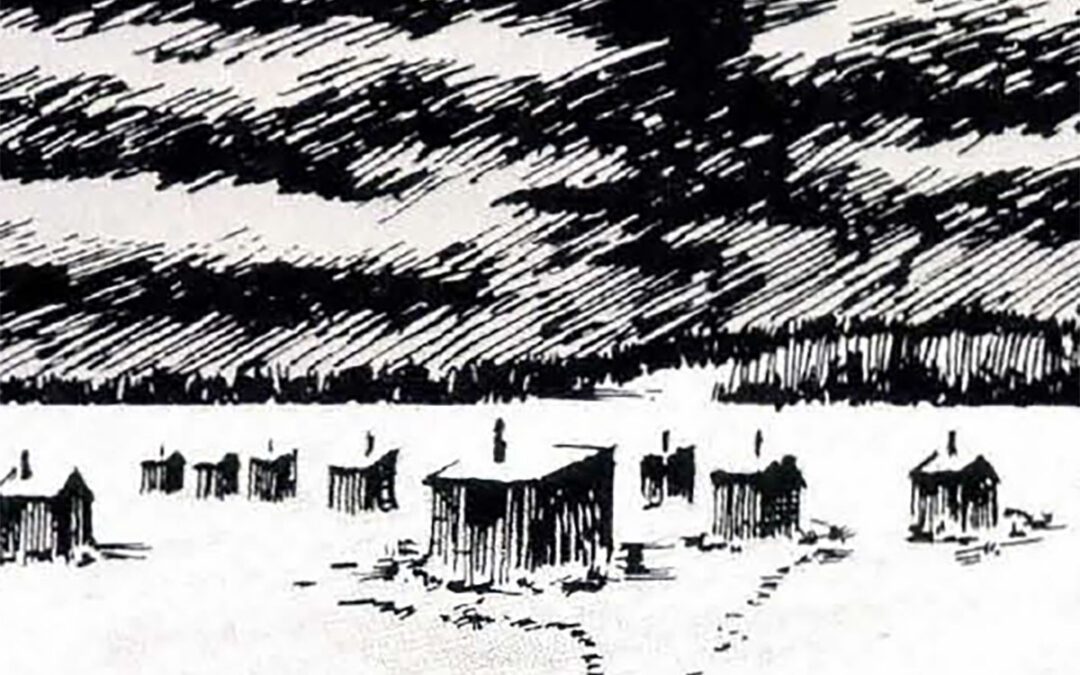

The Crane Island fishing grounds lay west of Waugoshance Point, at the extreme northwest tip of Michigan’s mitten-shaped lower peninsula. The point is a long, narrow tongue of sand, sparsely wooded, roadless and wild, running out into the lake at the western end of the Straits of Mackinac, with Crane Island marking land’s end. Both the island and the point are unpeopled. On the open ice of Lake Michigan, a mile offshore, Sweet and the other fishermen had their darkhouses.

Fishing was slow that morning. It was close to noon before a trout slid into sight under the ice hole where Sweet kept vigil. He maneuvered the wood minnow away and eased his spear noiselessly through the water. Stalking his decoy, the trout moved ahead a foot or two, deliberate and cautious. When it came to rest directly beneath him, eyeing the slow-moving lure with a mixture of hunger and wariness, he drove the spear down with a hard, sure thrust.

The steel handle was only eight or 10 feet long, but it was attached to the roof of the shanty by 50 feet of stout line. When Sweet felt the barbed tines jab into the fish he let go the handle and the heavy spear carried the twisting trout swiftly down to the reef 30 feet below.

The steel handle was only eight or 10 feet long, but it was attached to the roof of the shanty by 50 feet of stout line. When Sweet felt the barbed tines jab into the fish he let go the handle and the heavy spear carried the twisting trout swiftly down to the reef 30 feet below.

After the fish ceased struggling Sweet hauled it up on the line. When he opened the shanty door and backed out to disengage the trout, he noticed that the wind was rising and the air was full of snow. The day was turning blustery. Have to watch the ice on a day like that. Might break loose alongshore and go adrift. But the wind still blew from the west, on shore. So long as it stayed in that quarter there was no danger.

About an hour after he took the first trout the two men fishing near him quit their shanties and walked across the ice to his.

“We’re going in, Lew,” one of them hailed. “The wind is hauling around nor’ east. It doesn’t look good. Better come along.”

Sweet stuck his head out the door of his shanty and squinted skyward. “Be all right for a spell, I guess,” he said finally. “The ice’ll hold unless it blows harder than this. I want one more fish.”

He shut the door and they went on, leaving him there alone.

Thirty minutes later Sweet heard the sudden crunch and rumble of breaking ice off to the east. The grinding, groaning noise ran across the field like rolling thunder, and the darkhouse shook as if a distant train had passed.

Sweet had done enough winter fishing there to know the terrible portent of that sound. He flung open the shanty door, grabbed up his fix and the trout he had speared, and raced across the ice for the snow-clouded timber of Crane Island.

Halfway to the beach he saw what he dreaded, an ominous, narrow vein of black, zigzagging across the white field of ice.

When he reached the band of open water it was only ten feet across, but it widened perceptibly while he watched it, wondering whether he dared risk plunging in. Even as he wondered, he knew the chance was too great to take. He was a good swimmer, but the water would benumbingly cold, and he had to reckon, too, with the sucking undertow set up by100,000 tons of ice driving lakeward with the wind. And even if he crossed the few yards of water successfully, he would have little hope of crawling up on the smooth shelf of ice on the far side.

He watched the black channel grow to20 feet, to 90. At last, when he could barely see across it through the swirling snowstorm, he turned and walked grimly back to his darkhouse.

He had a stove there, and enough firewood to last through the night. He wanted desperately to take shelter in the shanty but he knew better. His only chance lay in remaining out in the open, watching the ice floe for possible cracks and breaks.

He turned his back resolutely on the darkhouse, moved to the center of the drifting floe, and began building a low wall of snow to break the force of the wind. It was slow work with no tool but his ax, and he hadn’t been at it long when he heard a pistol-sharp report rip across the ice. He looked up to see his shanty settling into a yawning black crack. While he watched, the broken-off sheet of ice crunched and ground back against the main floe and the frail darkhouse went to pieces like something built of cardboard.

Half an hour later, the two shanties of his companions were swallowed up in the same fashion, one after the other. Whatever happened now, his last hope of shelter was gone. Live or die, he’d have to see it through right in the open on the ice, with nothing between him and the wind save his snow wall. He went on building it.

He knew pretty well what he faced, but there was no way to figure his chances. Unless the ice field grounded on either Hog or Garden Island, at a place where he could get to the beach, some 60 miles of open water lay ahead between him and the west shore of Lake Michigan. There was little chance the floe would hold together that long, with a winter gale churning the lake.

There was little chance, too, that the wind would stay steady in one quarter long enough to drive him straight across. It was blowing due west now but before morning it would likely go back to the northeast. By that time he’d be out in midlake if he were still alive, beyond Beaver and High and the other outlying islands. And there, with a northeast storm behind him, he could drift more than one hundred miles without sighting land.

Sweet resigned himself to the fact that, when buffeted by wind and pounding seas, even a sheet of ice three miles across and two feet thick can stay intact only so long.

In midafternoon, hope welled up in him for a little while. His drift carried him down on Waugoshance Light, a lighthouse abandoned and dismantled long before, and it looked for a time as if he would ground against its foot. But currents shifted the direction of the ice field a couple of degrees and he went past only one hundred yards or so away.

Waugoshance was without fuel or food; no more than a broken crib of rock and concrete and a gaunt, windowless shell of rusted steel. But it was a pinpoint of land there in the vast gray lake. It meant escape from the icy water all around; it spelled survival for a few hours at least, and Sweet watched it with hungry eyes as his floe drifted past, almost within reach, and the squat red tower receded slowly in the storm.

By that time, although he had no way of knowing it, the search and rescue resources of an entire state were being marshaled in the hope of snatching him from the lake alive.

The two men who had fished with him that morning were still on Crane Island when the ice broke away. They had stayed on, concerned and uneasy, watching the weather, waiting for Sweet to come back to the beach. Through the snowstorm they had seen black water open offshore when the floe went adrift. They knew Sweet was still out there somewhere on the ice and they lost no more time. They piled into their car and raced for the hamlet of Cross Village, on the high bluffs of Sturgeon Bay 10 miles to the south.

There was little the Cross Villagers or anybody else could do at the moment to help, but the word of Sweet’s dramatic plight flashed south over the wires to downstate cities and on across the nation, and one of the most intense searches for a lost man in Michigan’s history got underway.

The theme was an old one. Puny man pitted against the elements. A flyspeck of humanity out there alone, somewhere in an endless waste of ice and water, snow and gale, staving off death hour after hour — or waiting for it, numb and half frozen, with cold — begotten resignation. None heard the story unmoved. Millions sat at their own firesides that winter night, secure and warm and fed, and pitied and wondered about Lewis Sweet, drifting unsheltered in the bitter darkness.

The theme was an old one. Puny man pitted against the elements. A flyspeck of humanity out there alone, somewhere in an endless waste of ice and water, snow and gale, staving off death hour after hour — or waiting for it, numb and half frozen, with cold — begotten resignation. None heard the story unmoved. Millions sat at their own firesides that winter night, secure and warm and fed, and pitied and wondered about Lewis Sweet, drifting unsheltered in the bitter darkness.

The fast-falling snow prevented much action for the first 24 hours. But the storm blew itself out Wednesday forenoon, and the would-be rescuers went into action.

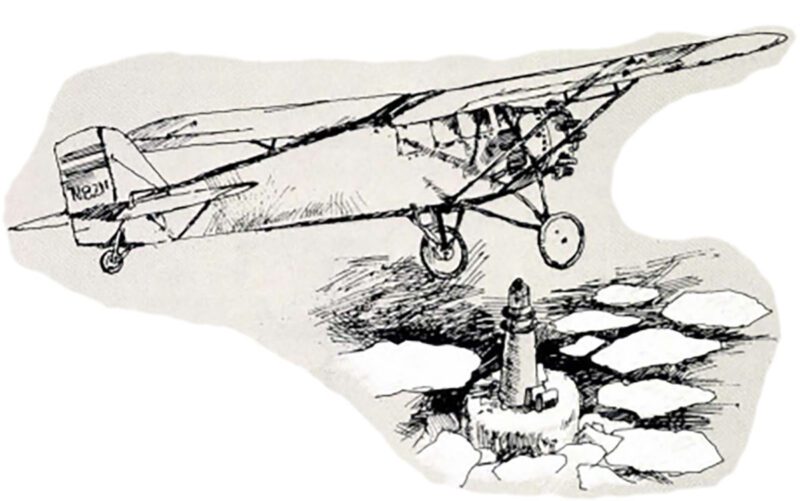

There was too much ice there in the north end of Lake Michigan for boats. The search had to be made from the air, and on foot along the shore of Waugoshance Point and around Crane Island, south into Sturgeon Bay and on the frozen beaches of the islands farther out.

Coast Guard crews and volunteers joined forces. Men walked the beaches for four days, clambering over rough hummocks of shore ice, watching for tracks, a thread of smoke, a dead fire, any sign at all that Sweet had made land. Other men scanned the ice fields and the outlying islands, Garden and Hog and Hat, from the air. Pilots plotted 2,000 square miles of lake and flew them systematically, one by one, searching for a black dot that would be a man huddled on a drifting floe.

Lewis Sweet, who on Monday of that week had hardly been known to anyone beyond the limits of his hometown, was now an object of nation-wide concern. Men bought papers on the streets of cities1,000 miles from Alanson, to learn what news there might be of the lost fisherman.

Little by little, hour by hour, hope ebbed among the searchers. No man could survive so long on the open ice. The time spun out — a day, then two days, three — and still the planes and foot parties found no trace of Sweet. By Friday night hope was dead. Life could not endure through so many hours of cold and storm without shelter, fire, or food. On Saturday, the last day of the search, those who remained in it looked only for a dark spot on the beach, a frozen body scoured bare of snow by the wind. At dusk the search was reluctantly abandoned.

Folks no longer wondered whether Lewis Sweet would be rescued, or how. Instead, they wondered whether his body would be found on some lonely beach when spring came, or whether the place and manner of his dying would never be known.

But Sweet had not died.

Twice more before dark on Tuesday he believed for a little time that he was about to escape the lake. The first time he saw Hat Island looming up through the storm ahead, a timbered dot on a gray sea that smoked with snow. His floe seemed to be bearing directly down on it and he felt confident it would go aground on the shingly beach.

No one lived on Hat. He would find no cabin there. But there was plenty of drywood for a fire and he had his big trout for food. He’d make out all right until the storm was over and he had no doubt that some way would be found to rescue him when the weather cleared. But even while he tasted in anticipation the immense relief of trading his drifting ice floe for solid ground, he realized that his course would take him clear of the island and he resigned himself once more to a night of drifting.

The next time it was Hog Island, much bigger but also without a house of any kind, that seemed to lie in his path. But again the wind and lake played their tricks and he was carried past, little more than a stone’s throw from the beach. As if to tantalize him deliberately, a solitary gull, a holdover from the big flock that bred therein summer, flew out from the ice hummocks heaped along the shore, alighted for a few minutes on his floe, and then soared casually back to the island.

“That was the first time in my life I ever wished for wings!” Sweet told me afterward.

That night was pretty bad. The storm mounted to a raging blizzard. With the winter darkness coming down, the section of ice where Sweet had built his snow shelter broke away from the main field suddenly and without warning. He heard the splintering noise, saw the crack starting to widen in the dusk only a few yards away. He gathered up his fish and his precious ax and ran for a place where the pressure of the wind still held the two masses of ice together, grinding against each other. Even as he reached it the crevice opened ahead of him, but it was only a couple of feet wide and he jumped across to the temporary safety of the bigger floe.

Again he set to work to build a shelter with blocks of snow. When it was finished he lay down behind it to escape the bitter wind. But the cold was numbing, and after a few minutes he got to his feet and raced back and forth across the ice to get his blood going again, with the wind-driven snow cutting his face like a whiplash.

He spent the rest of the night that way —lying briefly behind his snow wall for shelter, then forcing himself to his feet once more to fight off the fatigue and drowsiness that he knew would finish him if he gave in to it.

He was out in the open now, and the storm had a chance to vent its full force on the ice field. Before midnight the field broke in two near him again, compelling him to abandon his snow shelter once more in order to stay with the main floe. Again he had the presence of mind to take his ax and the trout along. The same thing happened once more after that, sometime in the small hours of the morning.

Toward daybreak the cold grew even more intense. And now the storm played a cruel prank. The wind hauled around to the southwest, reversing the drift of the icefield and sending it back almost the way it had come, toward the distant north shore of Lake Michigan. In the darkness, however, Sweet was not immediately aware of the shift.

Toward daybreak the cold grew even more intense. And now the storm played a cruel prank. The wind hauled around to the southwest, reversing the drift of the icefield and sending it back almost the way it had come, toward the distant north shore of Lake Michigan. In the darkness, however, Sweet was not immediately aware of the shift.

The huge floe — still some two miles across — went aground an hour before daybreak, without warning. There was a sudden crunching thunder of sound, and directly ahead of Sweet the edge of the ice rose out of the water, curled back upon itself like the nose of a giant toboggan, and came crashing down in an avalanche of two-ton blocks! The entire field shuddered and shook and seemed about to splinter into fragments, and Sweet ran for his life, away from the spot where it was thundering aground.

It took the field five or 10 minutes to lose its momentum and come to rest. When the splintering, grinding noise finally subsided, Sweet went cautiously back to learn what had happened. He had no idea where he was or what obstacle the floe had encountered.

To his astonishment, he found that he had brought up at the foot of White Shoals Light, one of the loneliest lighthouses in Lake Michigan, rising from a concrete crib bedded on a submerged reef, more than a dozen miles from the nearest land. The floe, crashing against the heavy crib, had buckled and been sheared and piled up until it finally stopped moving.

Sweet was close to temporary safety at last. Just 22 feet away, up the vertical concrete face of the crib, lay shelter and fuel, food and survival. Only 22 feet, four times his own height. But it might as well have been 22miles. For the entire crib above the waterline was encased in ice a foot thick, formed by freezing spray, and the steel ladder bedded in the concrete wall showed only as a bulge on the smooth, sheer face of the ice.

Sweet knew the ladder had to be there. He located it in the gray light of that stormy winter morning and went to work with his axe. He chopped away the ice as high as he could reach, standing on the floe, freeing the rungs one at a time. Then he stepped up on the first one, hung on with one hand, and went I on chopping with the other, chipping and worrying at the flinty sheath that enclosed the rest of the ladder.

Three hours from the time he cut the first chip of ice away he was within three rungs of the top. Three steps, less than a yard — and he knew he wasn’t going to make it.

His feet were wooden stumps on which he could no longer trust his weight. His hands had long since lost all feeling. They were so badly frozen that he had to look to make sure his fingers were hooked around a rung, and he could no longer keep a grip on the ax. He dropped it half a dozen times, clambering awkwardly down after it, mounting wearily up the rungs again. The first couple of times it wasn’t so bad, but the climb got more and more difficult. The next time he dropped the ax he wouldn’t be able to come back up the ladder. He took a few short, ineffectual strokes and the ax went clattering to the ice below: He climbed stiffly down and huddled on a block of ice to rest.

It’s hard to give up and die of cold and hunger with food and warmth only 20-odd feet overhead. Sweet didn’t like the idea. In fact, he said afterward, he didn’t even admit the possibility. There had to be some way to the top of that ice-coated crib, and he was bound he’d find it.

Hunched there on his block of ice, out of sight of land, with ice and water all around and the wind driving snow into his clothing at every buttonhole, the idea came to him. He could build a ramp of ice blocks up to the top of the crib!

The material lay waiting, piled up when the edge of the floe shattered against the base of the light. Some of the blocks were more than ten men could have moved but some were small enough for Sweet to lift. He went to work.

Three hours later he finished the job and dragged himself, more dead than alive, over the icy, treacherous lip of the crib.

Any man in normal surroundings and his right mind would have regarded Lewis Sweet’s situation at that moment as pretty desperate. White Shoals Light had been closed weeks before, at the end of the navigation season. Sweet was on a deserted concrete island 100 feet square, in midlake, with frozen hands and feet, in the midst of a January blizzard — and no other living soul had the faintest inkling where he was or that he was alive. It wasn’t exactly a rosy outlook, but in his 50-oddyears he had never known a more triumphant and happy minute!

The lighthouse crew had left the doors unlocked when they departed for the winter, save for a heavy screen that posed no barrier to a man with an ax. Inside the light, after his hours on the ice and his ordeal at the foot of the crib, the lost man found paradise.

Bacon, rice, dried fruit, flour, tea, and other supplies were there in abundance. There were three small kerosene stoves and plenty of fuel for them. There were matches. There was everything a man needed to live for days or weeks, maybe until spring!

At the moment, Sweet was too worn out to eat. He wanted only to rest and sleep. He cut the shoes off his frozen feet, thawed his hands and feet as best he could over one of the oil stoves, and fell into the nearest bed.

He slept nearly 24 hours. When he awakened Thursday morning, he cooked the first meal he’d had since eating breakfast tat home 48 hours before. It put new life into him, and he sat down to take careful stock of his situation.

He slept nearly 24 hours. When he awakened Thursday morning, he cooked the first meal he’d had since eating breakfast tat home 48 hours before. It put new life into him, and he sat down to take careful stock of his situation.

The weather had cleared and he could see the timbered shore of the lake both to the north and south, beckoning, taunting him, a dozen miles away. Off to the southeast he could even see the low shape of Crane Island, where he had gone adrift. But between him and the land, in any direction, lay those miles of water all but covered over with fields of drifting ice.

From the tower of the light Lake Michigan was a curious patchwork of color. It looked like a vast white field veined and netted with gray-green. That network of darker color showed where constantly shifting channels separated the ice fields. Unless and until there came a still, cold night to close all that open water, Sweet must remain a prisoner hereon his tiny concrete island.

At noon on Thursday, sitting beside his oil fire opening bloody blisters on his feet, Sweet heard the thrumming roar of a plane outside.

He knew it instinctively for a rescue craft sent out to search for him, and he bounded up on his crippled feet and rushed to a window.

But the windows were covered with heavy screen to protect them from wind and weather. No chance to wave or signal there. The door opening out on the crib, to the by which he had gained entrance light, was two or three flights below the living quarters. No time to get down there. There was a nearer exit in the lens room at the top of the tower, one flight up. He made for the stairs.

The pilot of the plane had gone out of his way to have a look at White Shoals on what he realized was a very slim chance. He didn’t really hope to find any trace of the lost man there and he saw no reason to linger. He tipped his plane in a steep bank and roared once around the light, a couple of hundred feet above the lake. Then, seeing nothing but a jungle of ice and snow piled the length of the reef, he leveled off and headed for his home field for a fresh supply of gas to carry him out on another flight. He must have felt pretty bad about it when he heard the story afterward.

While the pilot made that one swift circle Lewis Sweet was hobbling up the flight of iron stairs as fast as his swollen, painful feet would carry him. But he was too late. When he reached the lens room and stepped out through the door the plane was far out over the lake, disappearing swiftly in the south.

Most men would have lost heart then and there but Sweet had been through too much to give up at that point. Back in the living quarters he sat down and went stoically on with the job of first aid to his feet.

“It doesn’t hurt to freeze,” he told me with a dry grin months later, “but it sure hurts to thaw out!”

Before the day was over another plane, or the same one on a return flight, roared over White Shoals. But the pilot didn’t bother to circle that time and Sweet didn’t even make the stairs. He watched helplessly from a screened window while the plane winged on, became a speck in the sky, and vanished.

Sweet was convinced then that if he got back to shore he’d have to do so on his own. It was plain that nobody guessed his whereabouts, or even considered the empty lighthouse a possibility.

After dark that night he tried to signal the distant mainland. There was no way for him to put the powerful beam of the light in operation, or he would almost certainly have attracted attention at that season. But he rigged a crude flare, a ball of oil-soaked waste on a length of wire, and went out on the balcony of the lens room and swung it back and forth, hoping its feeble red spark might be seen by someone on shore.

Twenty miles away, at the south end of Sturgeon Bay, he could see the friendly lights of Cross Village winking from their high bluff. How they must have mocked him!

On Friday morning he hung out signals on the chance that another plane might pass. But no one came near the light that day, and the hours went by uneventfully. Fresh blisters kept swelling up on his feet and he opened and drained them as fast as they appeared. He cooked and ate three good meals, and at nightfall he climbed back to the lens room, went outside in the bitter wind, and swung his oil rag beacon again for a long time. He did that twice more in the course of the night, but nothing came of it.

The lake still held him a prisoner Saturday. That night, however, the wind fell, the night was starlit and still and very cold. When he awoke on Sunday morning there was no open water in sight. The leads and channels were covered with new ice as far as he could see, and his knowledge of the lake told him it was ice that would bear a man’s weight.

Whether he would encounter open water before he reached shore there was no way to guess. Nor did it matter greatly. Sweet knew his time was running out. His feet were in terrible shape and he was sure the search for him had been given up by this time. This was his only chance and he’d have to gamble on it. In another day or two he wouldn’t be able to travel. If he didn’t get away from White Shoals today he’d never leave it alive.

How he was to cross the miles of ice on his crippled feet he wasn’t sure. He’d have to take that as it came, one mile at a time.

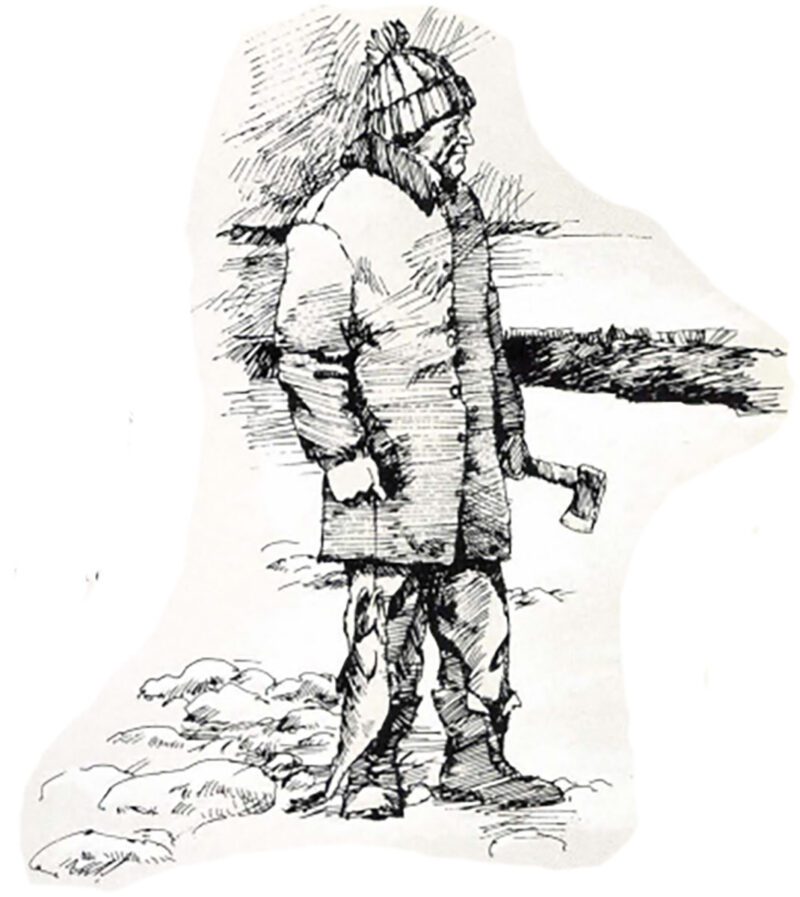

His feet were too swollen for shoes, but he found plenty of heavy woolen socks in the lighthouse. He pulled on three or four pairs, and contrived to get into the heavy rubbers he had worn over his shoes when he was blown out into the lake on Tuesday.

When he climbed painfully down from the crib that crisp Sunday morning and started his slow trek over the ice toward Crane Island he took two items along, his ax and the frozen trout he had speared five days before. If he succeeded in reaching shore they meant fire and food. They had become symbols of his fierce, steadfast determination to stay alive. So long as he kept them with him he was able to believe he would not freeze or starve.

Now an odd thing happened, one of those ironic quirks that seem to be Destiny’s special delight at such times. At the very hour when Sweet was climbing down from the lighthouse and moving across the ice that morning, three of us were setting out from the headquarters of Wilderness State Park, on Big Stone Bay on the south shore of the Straits 10 miles east of Crane Island, to have a final look for his body.

Floyd Brunson, superintendent of the park, George Laway, a fisherman living on Big Stone, and I had decided on one more last-hope search along the ice-fringed beach of Waugoshance Point.

We carried no binoculars that morning. We left them behind deliberately to eliminate useless weight, certain we would have no need for them. Had we had a pair along as we snowshoed to the shore and searched around the ice hummocks on the sandy beach, and had we trained the glasses a single time toward White Shoals Light — a far-off gray sliver rising out of the frozen lake — we could not possibly have failed to pick up the tiny black figure of a man crawling at snail’s pace over the ice.

Had we spotted him by nightfall, we could have had him in a hospital, where by that time he so urgently needed to be and where he was fated to spend the next 10 weeks while surgeons amputated all his fingers and toes and his frozen hand and feet slowly healed.

But the hospital was still two days away. Toward noon Brunson and Laway and I trudged back from our fruitless errand, never suspecting how close we had come toa dramatic rescue of the man who had been sought for five days in the greatest mass search that lonely country had ever seen.

Lewis Sweet crept on over the ice all that day. His progress was slow. Inside the heavy socks he could feel fresh blisters swelling on his feet. They puffed up until he literally rolled on them as he walked. Again and again he went ahead a few steps, sat down and rested, got up and drove himself doggedly on. At times he crawled on all fours.

He detoured around places where the new ice looked unsafe. Late in the afternoon he passed the end of Crane Island, at about the spot where he had gone adrift. Land was within reach at last and night was coming on, but he did not go ashore. He had set his sights on Cross Village as the nearest place where he would find humans, and he knew he could make better time on the open ice than along the rocky beach of Sturgeon Bay.

Late that day, Sweet believed afterward, his mind faltered for the first time. He seemed to be getting delirious and found it hard to keep his course. At dark he stumbled into a deserted shanty on the shore of the bay, where fishermen sometimes spent a night. He was still seven miles short of his goal.

The shanty meant shelter for the night and in it he found firewood and a rusty stove, but no supplies except coffee and a can of frozen milk. He was still carrying his trout but he was too weak and ill now to thaw and cook it. With great effort he succeeded in making coffee. It braced him and he lay down on the bunk to sleep.

Before morning he was violently ill with cramps and nausea, perhaps from lack of food or from the frozen milk he had used with his coffee. At daybreak he tried to drive himself on toward Cross Village but he was too sick to stand. He lay helpless in the shanty all day Monday and through Monday night, eating nothing.

Tuesday morning, he summoned the little strength remaining to him and started south once more, hobbling and crawling over the rough ice of Sturgeon Bay. It was quite a walk, but he made it. Near noon of that day, almost a week to the hour from the time the wind had set him adrift on his ice floe, he stumbled up the steep bluff at Cross Village and called to a passing Indian for a hand.

Tuesday morning, he summoned the little strength remaining to him and started south once more, hobbling and crawling over the rough ice of Sturgeon Bay. It was quite a walk, but he made it. Near noon of that day, almost a week to the hour from the time the wind had set him adrift on his ice floe, he stumbled up the steep bluff at Cross Village and called to a passing Indian for a hand.

Alone and unaided, Lewis Sweet had come home from the lake! When the Indian ran to him he put down two things he was carrying — a battered ax that had been dulled against the iron ladder of White Shoals Light, and a big lake trout frozen hard as granite.

Editor’s Note: this article originally appeared in the 1984 September/October issue of Sporting Classics.

Classic writing remains “classic” only insofar as people want to read it. Angling historians may study the evolution of tackle or tying techniques, or perhaps the methods of fishing used hundreds of years ago, but the wonderful stories about fishing are read and reread only because they give pleasure today; because they give us insights into why we fish and the nature of our passion; and because they are well written. This book offers sixteen of the best classic fishing stories that have stood the inescapable test of time. Buy Now

Classic writing remains “classic” only insofar as people want to read it. Angling historians may study the evolution of tackle or tying techniques, or perhaps the methods of fishing used hundreds of years ago, but the wonderful stories about fishing are read and reread only because they give pleasure today; because they give us insights into why we fish and the nature of our passion; and because they are well written. This book offers sixteen of the best classic fishing stories that have stood the inescapable test of time. Buy Now